October - Delhi High Court

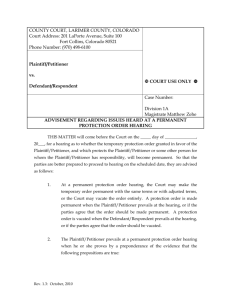

advertisement