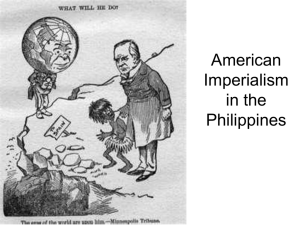

Philippine History & Culture Course Outline

advertisement