Agency Law as Asset Partitioning

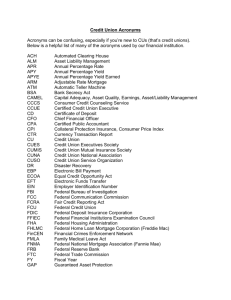

advertisement