Independent and Court-Ordered Forensic

advertisement

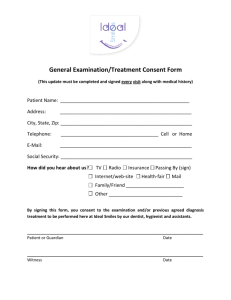

Independent and Court-Ordered Forensic Neuropsychological Examinations Official Statement of the National Academy of Neuropsychology Approved by the Board of Directors 10/14/03 Purpose: The responsibilities of the neuropsychologist in the context of performing an independent forensic examination differ from those of the clinical examination. Because neuropsychological training typically occurs in clinical contexts, the transition to the independent forensic examiner role may result in uncertainty about how to negotiate the unique responsibilities of this role. The purpose of this paper is to identify some of the areas of distinction between independent forensic and clinical examinations and to offer recommendations for those performing independent and court-ordered forensic neuropsychological examinations. Much of the information pertaining to independent forensic examinations also applies to forensic examinations in general. The Neuropsychologist-Retaining Party Relationship: An independent forensic neuropsychological examination, also referred to as an independent medical examination (IME), independent psychological examination, or compulsory examination in some jurisdictions, is performed by a neuropsychologist who is hired as an independent contractor by a third party, such as an insurance company, an attorney, or the court to make a determination regarding neuropsychological functioning. Referral questions in civil litigation often involve determination of the presence or absence of neurological and/or psychiatric disorders, causality related to a specific event or injury, prognosis, medical necessity of treatment, and/or disability status. In criminal litigation, the neuropsychological examination may be used to assist in determining competency to stand trial, issues of responsibility for the crime, or in sentencing/mitigation. The nature of the examination may range from a relatively brief clinical interview to a comprehensive examination that includes extensive psychological or neuropsychological test administration. The role of the neuropsychologist when performing an independent neuropsychological examination is narrowly defined. The neuropsychologist has been hired by a third party seeking answers to specific questions related to brain-behavior relationships. In contrast to clinical contexts, the neuropsychologist does not work for the person being examined. As a result, the examination parameters and professional requirements are often different. The neuropsychologist must be aware of the overlapping yet often quite distinct professional and ethical conduct required in independent examination contexts. The Neuropsychologist-Patient Relationship: The relationship of the neuropsychologist with the examinee when performing an independent neuropsychological examination parallels but also differs in important ways from that of NP IMEs Page 2 of 10 the clinical examination, with limits on the usual neuropsychologist-patient relationship. The neuropsychologist has been hired by a third party seeking answers to specific questions. In the pursuit of such answers, the role of the neuropsychologist in independent forensic contexts is similar to that of clinical contexts in a number of ways. Consistent with the Ethics Code of the American Psychological Association (2002), the neuropsychologist strives to conduct a proper examination (Ethical Standard 9) and practices only within the bounds of professional competence (Ethical Standard 2). The examination procedures that comprise proficient clinical examinations are also required for forensic examinations. In contrast to the above similarities, differences between clinical and forensic roles exist as well. With independent forensic examinations the neuropsychologist does not work for the person being examined, nor is the neuropsychologist the agent of the examinee. The goal is to determine the examinee’s neuropsychological status as accurately as possible whether or not the conclusions advance or compromise the examinee’s interests. As a result, the relationship between the neuropsychologist and the examinee is different. These differences are seen with regard to informed consent (see Informed Consent section below), privilege and confidentiality (see Confidentiality section below), the information provided to the examinee following the examination regarding the results (see Presentation of Findings and Release of Raw Data sections below), and typically an absence of follow-up treatment (see Termination section below). In summary, neuropsychologists do not have the same obligations to an examinee in an independent forensic examination that they do in a clinical examination. Nevertheless, certain professional responsibilities exist whenever a neuropsychologist conducts an examination. Therefore, although no true neuropsychologist-patient relationship should be considered to exist within the context of a forensic neuropsychological evaluation, the neuropsychologist is nonetheless obligated to perform his/her evaluation in a manner consistent with recognized ethical codes and the responsibilities inherent in any professional clinical evaluation (see Scope of Interpretation section). Objectivity: A primary responsibility of neuropsychologists performing independent neuropsychological examinations is to strive to examine neuropsychological status objectively. Interpretation of results should ideally be made without preconceived ideas about the examinee and with proper attention to the potential effects of bias. Attempts to satisfy the examinee or align with the retaining third party have the potential to bias conclusions and recommendations. Care should be taken to consider potential biases and take action to guard against them (Sweet & Moulthrop, 1999). Confidentiality: As in other professional contexts, neuropsychologists have a responsibility to maintain examinee confidentiality, except to report findings to the retaining party and as required by law. Legal reporting requirements may include situations of danger to oneself, danger to others, and neglect or abuse of children or the elderly. With independent examinations, the retaining party may hold the privilege regarding communication of findings. The neuropsychologist maintains responsibility for knowing who holds the privilege regarding communication of findings. Examinees NP IMEs Page 3 of 10 should be informed of the limits of confidentiality as part of the informed consent process prior to beginning the examination (Committee on Ethical Guidelines for Forensic Psychologists, 1991; Sweet, Grote, & van Gorp, 2002). Informed Consent and Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: At the outset of an independent examination, the neuropsychologist should disclose fully the nature of the relationship between him/herself and the retaining party, explain how such a relationship might be perceived as representing a potential conflict of interest between the retaining party and the examinee, and assure the examinee of the continued adherence to professional ethics. Confidentiality issues should be discussed (as described above). In some independent examination contexts, the examinee is not required to provide consent to the examination. In such situations, if the examinee refuses to read and/or sign an informed consent form, the neuropsychologist should nevertheless provide a verbal description of the content contained in the form and seek the examinee’s assent to engage in the examination (Fisher, Johnson-Greene, & Barth, 2002). In other contexts, informed consent is required. It is the neuropsychologist’s responsibility to know the consent requirements of the examination context. The consent process should be documented in the examination report, if one is generated. A sample informed consent form is contained in the appendix. The reader is also referred to the separate NAN position paper on informed consent (Johnson-Greene & NAN Policy and Planning Committee, in press). Third Party Observers: Requests to have independent and other forensic neuropsychological examinations observed by an interested party or recorded in an audio or video format are common. In some jurisdictions, examinees have a statutory right to have their independent examinations observed or recorded. Observation by an involved third party and recording of a neuropsychological examination are problematic and raise complex issues, such as whether the results could be invalidated and how test security will be maintained. The National Academy of Neuropsychology (NAN) position paper on third party observers, as well as that of the American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology (AACN), apply in this context (AACN, 2001; NAN, 2000a). Forensic examiners who receive such requests need to be knowledgeable of the relevant issues and are encouraged to respond only after careful consideration. Examination Procedures: The neuropsychologist maintains responsibility for conducting an examination adequate to answer the questions defining the examination. That is, the neuropsychologist determines which procedures are required to answer the questions posed by the retaining party. A request may be made by the retaining party to administer certain tests. If the neuropsychologist believes that different, or additional, measures should be used, he/she should explain the reasoning behind the proposed tests/procedures and seek approval from the retaining party. If the retaining party indicates that the measures preferred by the neuropsychologist may be given, but will not be reimbursed, the neuropsychologist must make a decision about how to proceed that upholds high standards of professional practice, such as administering the additional tests pro bono or refusing to perform the examination. If the retaining party requests that specific measures be administered that the neuropsychologist considers inappropriate, the NP IMEs Page 4 of 10 neuropsychologist should explain why the measures are considered inappropriate in an attempt to educate the retaining party. If the retaining party insists on the use of measures that the neuropsychologist considers inappropriate, the neuropsychologist should consider whether it is advisable to accept the referral. The neuropsychologist may be ethically obligated to document in the examination report any constraints placed on the examination. The neuropsychologist maintains responsibility for the measures administered and should accept, extend, or reject recommendations based on the appropriateness of such recommendations for a given examination. There may be instances in which the neuropsychologist is asked to provide the retaining party with a list of the examination measures in advance of the examination. To minimize the possibility of successful coaching of the examinee on how to approach the test administration, the neuropsychologist may choose to provide related but nonspecific information, such as a description of the neuropsychological domains to be assessed or a list of all measures in one’s armamentarium, without declaring which measures will be selected for the examination in question. Scope of Interpretation: Some retaining parties may request that a determination be made with regard to the presence or absence of a specific neuropsychological condition and request that no other conditions be discussed. However, if failure to document another condition can result in harm to the examinee, the option of nondisclosure may not be ethically viable. If this becomes a point of concern, the neuropsychologist should seek clarification from the retaining party regarding the reason for the limitation posed, present his/her reasoning regarding the presence of a different condition, and consider the judiciousness of accepting cases in which limitations are placed on independence. Presentation of Findings: Independent neuropsychological examinations typically differ from clinical examinations regarding the provision of feedback and release of results. With independent neuropsychological examinations, neuropsychologists typically do not provide the examinee with feedback regarding results, conclusions, or recommendations. Reports are released to the retaining party and not to examinees or their family members, doctors, lawyers, or other representatives without the permission of the retaining party. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996 does not seem to alter examinee access to neuropsychological records in forensic contexts (Connell & Koocher, 2003; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1996). HIPAA states that information compiled in anticipation of use in civil, criminal, and administrative proceedings is not subject to the same right of review and amendment as is health care information in general [§164.524(a)(1)(ii)] (also see section below on State and Federal Laws). However, some exceptions to the typical release mandates do exist. For example, if the examinee reports suicidal intent, the neuropsychologist must report such findings to the appropriate authorities. In addition, the concept of due diligence underscores the neuropsychologist’s ethical and professional responsibility to address substantial medical problems that were not considered in the referral question. If in the course of the examination the neuropsychologist discovers important and previously unrealized health NP IMEs Page 5 of 10 abnormalities, the neuropsychologist has a responsibility to inform the examinee and to suggest that treatment be pursued from an appropriate health care professional. In addition to verbal feedback, such findings and recommendations should be documented in the written report. There may be instances in which the substantial health concern is not suspected until after the neuropsychologist-examinee contact has ended (e.g., during interpretation of the test data). In such instances, the neuropsychologist should clearly document the findings, request that the retaining party convey the information to the examinee or other appropriate parties, and follow-up to ensure that such information has been conveyed. Revising Reports: The retaining party may request that reports be modified with regard to format and/or content. However, there are very few acceptable reasons to modify reports once they have been completed. A request that comes from an invested party and reflects that party’s self-interest in the outcome of a case represents a request for the neuropsychologist to become a biased advocate, rather than an objective expert. As a result, such requests should be considered carefully in reference to standards for objectivity. Modifications must ultimately reflect the beliefs of the neuropsychologist, not those of another party. Modifications involving either additions to the report or omissions from the report might well be considered equally problematic if they do not reflect the examiner’s opinions. Neuropsychologists should retain copies of all completed reports, including those later modified. Release of Raw Data: Issues related to test security and release of data have been discussed at length in the psychology and neuropsychology literature. The 2002 APA Ethics Code (Standards 9.04 and 9.11) and the NAN position paper on test security apply in this context (e.g., NAN, 2000b). Termination of the Relationship with the Retaining Party: The relationship between the neuropsychologist and the retaining third party may end when payment for services is made, when the report is submitted, or when testimony has been provided. The neuropsychologist should determine beforehand when the relationship will be considered terminated, as the neuropsychologist’s ability to respond to subsequent requests for reports or data may be determined by the status of the relationship with the retaining party. Similarly, the nature of who holds the privilege (who is responsible for protecting the examinee’s confidentiality) regarding the neuropsychological results/data following termination of the relationship should be clarified in advance. In rare cases, an examinee may return to the neuropsychologist to request treatment from that individual. If the independent examination relationship has ended and the forensic action that initiated the examination has been completed, the neuropsychologist may consider providing such treatment, or refer them to another qualified professional. Once a treating relationship has been established, further independent examinations would be prohibited. Licensing Board and Ethics Committee Complaints: The American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology (AACN) recently drafted an official position on ethical NP IMEs Page 6 of 10 complaints made against neuropsychologists during legal proceedings (AACN, in press). The AACN paper notes the importance that appropriate complaints can serve for the protection of the public and the integrity of the profession. The paper also states that some complainants may have more self-serving motivations. Suggestions for processing complaints involving forensic examinations are offered. The National Academy of Neuropsychology concurs with the position of AACN regarding ethics complaints in forensic cases. State and Federal Laws: Jurisdictions differ with respect to the issues discussed in this paper. Some state laws do not specify that any entity other than the examinee is the client, whereas others acknowledge that neuropsychological services may be retained by an entity other than the examinee. State and federal laws provide guidelines for the maintenance and dissemination of records and raw test data and must be considered primary when determining how to respond to requests for records. Conclusions: Neuropsychologists are responsible for maintaining the highest standards of professional practice when performing independent and court-ordered forensic examinations and must strive to maintain true independence and objectivity. Although a true neuropsychologist-patient relationship is not considered to exist within the context of a forensic neuropsychological evaluation, neuropsychologists nevertheless have ethical responsibilities to both the retaining party and the examinee. Shane Bush, PhD and the NAN Policy and Planning Committee Jeffrey Barth, Ph.D., Chair Neil Pliskin, Ph.D., Vice-Chair Sharon Arffa, PhD Bradley Axelrod, Ph.D. Lynn Blackburn, PhD David Faust, Ph.D. Jerid Fischer, Ph.D. J. Preston Harley, PhD Robert Heilbronner, Ph.D. Glenn Larabee, Ph.D William Perry, PhD Antonio Puente, PhD Cheryl Silver, Ph.D. NP IMEs Page 7 of 10 References American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology (2001). Policy statement on the presence of third party observers in neuropsychological assessment. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 15, 433-439. American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology (in press). Official position of the American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology on ethical complaints made against clinical neuropsychologists during adversarial proceedings. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. American Psychological Association (2002). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. American Psychologist, 57 (12), 1060-1073. Committee on Ethical Guidelines for Forensic Psychologists (1991). Specialty guidelines for forensic psychologists. Law and Human Behavior, 15 (6), 655-665. Connell, M., & Koocher, G.P. (2003). HIPAA and forensic practice. American Psychology Law Society News, 23 (2), 16-19. Fisher, J.M., Johnson-Greene, D., & Barth, J.T. (2002). Examination, diagnosis, and interventions in clinical neuropsychology in general and with special populations: An overview. In S. Bush & M. Drexler (Eds.), Ethical Issues in Clinical Neuropsychology, 3-22. Lisse, NL: Swets & Zeitlinger Publishers. Johnson-Greene, D., & NAN Policy and Planning Committee (in press). Informed consent: Official statement of the National Academy of Neuropsychology. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. National Academy of Neuropsychology (2000a). Presence of third party observers during neuropsychological testing: Official statement of the National Academy of Neuropsychology. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 15 (5), 379-380. National Academy of Neuropsychology (2000b). Test security: Official statement of the National Academy of Neuropsychology. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 15 (5), 383-386. Sweet, J.J., Grote, C., & van Gorp, W.G. (2002). Ethical issues in forensic neuropsychology. In S. Bush & M. Drexler (Eds.), Ethical Issues in Clinical Neuropsychology, 103-133. Lisse, NL: Swets & Zeitlinger Publishers. Sweet, J.J., & Moulthrop, M.A. (1999). Self-examination questions as a means of identifying bias in adversarial assessments. Journal of Forensic Neuropsychology, 1 (1), 73-88. NP IMEs Page 8 of 10 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (1996). Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Accessed October 2, 2003 at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/hipaa. NP IMEs Page 9 of 10 APPENDIX Sample Informed Consent Independent and Court-Ordered Forensic Neuropsychological Examinations This is a general template for informed consent that may not apply to one’s particular circumstances or jurisdiction. It is recommended that psychologists seek advice from personal counsel to determine if this consent is appropriate for their circumstances and jurisdiction. Referral Source: You have been referred for an independent forensic neuropsychological examination (i.e., evaluation of your thinking abilities) by (name of referral) Nature and Purpose: The goal of neuropsychological assessment is to determine if any changes have occurred in your attention, memory, language, problem solving or other thinking skills. The current examination has been requested because of your claim of neuropsychological injury. It is common when someone is in an accident, is injured, and sees doctors for evaluation and treatment, that the insurance carrier or an attorney representing the defense in a law suit will request an examination by an expert neuropsychologist of their choosing. A neuropsychological examination will include an interview, where questions will be asked about your background and current medical symptoms. Additionally, standardized tests and other techniques my be used, including, but not limited to, asking questions about your knowledge of certain topics, reading, drawing figures and shapes, learning word lists or stories, viewing printed material, and manipulating objects. Your task is to answer questions as accurately as you can; for example, when discussing your problems, do not minimize significant problems, but also do not exaggerate lesser concerns. You are to give your best effort during the testing. This does not mean that you have to get every answer or problem correct, for no one ever does. However, you do have to give your best effort. Part of the examination will address the accuracy of your responses, as well as the degree of effort that you exert on the tests. Foreseeable Risks, Discomforts, and Benefits: For some individuals, neuropsychological examinations can cause fatigue, frustration, and anxiousness. An attempt will be made to help you minimize these factors. The results of this examination may either support or not support your claim. NP IMEs Page 10 of 10 Limits of Confidentiality: The results of this examination will be forwarded to . If your claim involves a lawsuit, at minimum, the defense attorney and staff and your attorney and staff will have access to the results of this examination. Should your case proceed to trial, those involved in the trial will be exposed to the results of the examination, and the court record will be available for anyone to review. Beyond the above, confidential information about you obtained during the examination can ordinarily be released only with your written permission. There are some special circumstances that can limit confidentiality, which include, but are not limited to, (a) a statement of intent to harm yourself or others, (b) statements indicating harm or abuse of children or vulnerable adults, and (c) a subpoena from a court of law. I have read and agree with the nature and purpose of this examination and to each of the points listed above. I have had an opportunity to clarify any questions and discuss any points of concern before signing. Examinee Signature Date Parent/Guardian or Authorized Surrogate (if applicable) Date Witness Signature Date / / / / / /