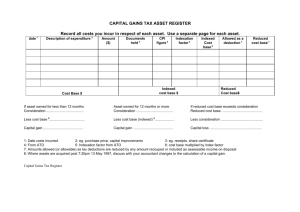

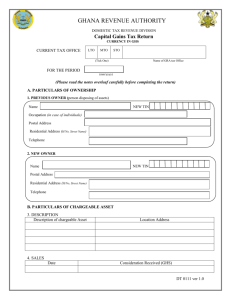

CGT1 - Capital Gains Tax, an introduction

advertisement