PART II– CHAPTER 5 - GENRES & INTERTEXTUALITY This

advertisement

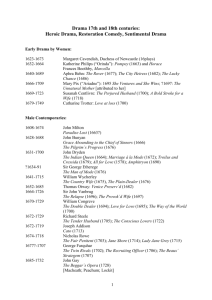

1 PART II– CHAPTER 5 - GENRES & INTERTEXTUALITY This chapter is really a catalogue and its main target is to offer a panorama of the more or less arbitrary classification of literary works into various genres. It will serve to introduce a small tool-box of terms and concepts. For it may prove useful to situate and roughly define any given literary text in terms of genre, if only to be aware of any variation from one norm, one standard or another. Of course, texts and works do not have to be rigidly classified. Except for a few cas d'école, they stand in a rather loose relationship to set categories. Sometimes, there are echoes and resonances from one well-known work to another. These may be quotations, or merely evocations and allusions. A novel may imitate a famous passage from another. Or it may be characters, etc.. Allusions to Shakespeare, in particular, are numerous in English literature, but also simply in the press, who keep turning out titles with more or less oblique allusions to literary titles and catch-phrases. This is called intertextuality. The intertext is that part or that region of texts that overlap, the border zone by which texts are coterminous with one another. One could go as far as to say that any text is a rewriting and a combination of a great many other texts. It is not merely a matter of deliberate imitation, as in the case of a parody, which is meant to mock and deride the imitated work, or in the case of pastiche, which, as defined by the American critic Fredrik Jameson, is deprived of any intention of mockery. Pastiche is one important feature of postmodernist fiction, for which one of the great pleasures of reading (and writing) resides in a game of intertextual recognition. The intertext could be defined as the memory of literature (not the Read-Only Memory, but really the Random-Access Memory of literature). At bottom, all literary works in a given language and culture are using the same words. Much in the same way, they all have the same predecessors and influences and come are developments of one and the same history of literature. So that a given text can hardly be read with any profit or any great pleasure by someone who would be in total ignorance of the literature and culture it belongs to. The intertextual dimension of a text may be developed to such a point that its own language, or mode of expression, mixes with one or several others. One example of this would be Michel Tournier's Les Limbes du pacifique, which is a rewriting or a pastiche of Defoe's Robinson Crusoe. Tournier's novel is not only a mixture of the discourses of two implied authors and personae but also a mixture of two languages, two epochs, two cultures. It is a graphic case of what the Russian critic Mikhail Bakhtin has called hybridisation: What is hybridization? It is a mixture of two social languages within the limits of a single utterance, between two different linguistic consciousnesses, separated from one another by an epoch, by social 2 differentiation or by some other factor. For Bakhtin, when the phenomenon of hybridisation is pushed to the limit and the two languages are no longer so neatly recognisable and start interfering more than two such language, then the genre is in a state of historical evolution which Bakhtin calls dialogism. Dialogism is not a case of clear-cut dialogue, as in drama for instance, but it is a state of the literary text which is produced by the interplay of several literary languages. For Bakhtin, the novel is the only truly dialogic genre. This means that, for him, the novel is the most accomplished state of literature, which all other genres ultimately tend to follow. According to him, all the genres of literature undergo a process of novelisation (romanisation in the French translation). For Bakhtin, all literature aspires to the condition of the novel (this being said to strike up an intertextual relationship with Walter Pater, for whom ‘All art aspires to the condition of music’). Whether or not that theory may be debatable, one may have the global impression that, in the Western world generally speaking and for English literature at least, the dominant genre for the Middle-Ages is poetry, for the Renaissance, drama, and for Modern Times, Fiction. For the birth of the novel, as such, is generally situated in the 18th century. This, of course, is highly questionable, and is only justified here to explain the rather arbitrary choice of coming down to the very prosaic realm of generic classification in this chronological order– Poetry, Drama, Fiction. 1 2 Recommended reading: F. Grellet, A Handbook of Literary Terms, pp. 33-46. 61-70; 126-136. Bakhtin, M. M., 1981, The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays by M. M. Bakhtin, ed. Michael Holquist, Austin: University of Texas Press, p. 358. Poetry The most ancient poems, in Western literature at least, are called epics (des épopées), from the Greek epos (which is also an English word). The word is both a substantive and an adjective–an epic is a piece of epic poetry. The most well-known examples are Homer's Iliad and Odyssey, later imitated by Virgil's Aeneid or Milton's Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained. Chaucer's Canterbury Tales are also reminiscent of the epic. As in these cases, an epic recounts the origins of a nation, or else historical or legendary events of such an importance as to change the destiny of a people. Remarkably, the epic genre dates back from a time before the concept of History as such. The genre is mainly defined by two major characteristics–an epic is both narrative and pertains of the legendary. As a narrative poem, an epic may be considered as entertaining a close relationship with fiction. In his reflections of literary aesthetics, mirrored by the elucubrations of Stephen Dedalus in The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, James Joyce divides the art of writing into ‘three forms progressing from one to the next’– the lyrical, the epic and the dramatic. Remarkably, his novel Ulysses (1922) developed from the idea of a rewriting of Homer's Odyssey and he has defined it as ‘an epic of two races (Israelite-Irish) and at the same time the cycle of the human body as well as a little story of a day (life).’ In the case of particularly long narrative poems, which may evolve in cycles, an epic is sometimes called a saga /'sa:g ?/. The word is borrowed from the Icelandic and mainly refers to the Medieval legends of Northern Europe, as for instance the Finnish Kalevala or the Germanic Niebelungen Lied. In English literature, the Old English poems like Beowulf and The Battle of Maldon are not quite long enough to be called sagas, but they do belong to the epic. In the case of Medieval texts, the marvelous is an equivalent of the legendary dimension of classical epics. Even the Venerable Bede, one of the very first English historians, does not make a clear cut difference between the miraculous and what our modern times call historical facts. Precisely because they contain supernatural elements, which give them a metaphysical and a religious relevance, most epics may be called myths. It is this mythological dimension which has justified the application to literature of structuralist methods of analysis, especially after the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss or the historian of religions Sir James Frazer, for instance. In the wake of the psychologist Carl Gustav Jung, these considerations have also encouraged many critics to view literature as a series of archetypal patterns, recurring in various works over the ages. Because epics are mostly concerned with high deed and the noble characters of heroes (demi-gods in classical literature or simply great men in more recent times), the epic genre is also called the heroic genre. The predilection for elevated, lofty subjects makes the epic bear close resemblances to the tragic. For this reasons, Shakespeare's historical plays are essentially tragedies, but it would make some sense to speak of their epic dimension. In the 17th and the 18th century, and especially that period of literary history which is called the Augustan Age of English Literature, poets like Pope or Dryden have imitated the style of the epic as an instrument of satire and written long poems called Mock-Heroic. Virgil's Aeneid famously begins by these words: ‘Arma virumque cano’– ‘Of arms and men I sing.’ For the origin of literature is poetry and the origin of poetry is singing. Shakespeare is called the Bard. The Ancient Greek bard was called α'οιδος (in French l'aède). The song is α'οιδη–the ode. Several of the greatest romantic poems in the English language are odes, as for instance Shelley's Ode to the West wind or Keat's Ode on a Greacian Urn. Yet another major form of earlier English literature is musical–the ballad, which belonged first to the oral tradition. Those were the Folk Ballads, later printed as Broadsides Ballads. In the late Middle-Ages and Renaissance the ballad served as an ancestor of the newspaper and was a means of peddling news. But it was also a literary art form in its own right, as testified in the 14th century by the anonymous Ballad of Robin Hood. The various modes and forms of poetry will be examined in further details in a later chapter of this lecture. Still there is one concept which belongs to the poetic style or so called ‘poetic’ themes rather than to the poetic genre strictly speaking, but which lies at the border between poetry and fiction. It is the notion of romance, which gave the etymological root for the novel in French, as well as in German–roman. A romance is a medieval tale which tells of courtly love (l'amour courtois). The characters are idealised and the plot contains elements of the supernatural, like dragons and enchanters. One good example is the 14th -century anonymous romance Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. A modern romance is a novel based on an idealistic and idealised love-story, on so-called romantic love by definition. The characters and actions of a romance often partake of allegory, which is to say that they are embodiments, even more than personifications, of abstract notions or ideals. The line between the genres is not always so obvious to draw. It may be safer to think in terms of forms rather than in terms of themes. For any theme whatsoever may be dealt with in poetry, drama or fiction. Only the form will vary sometimes. Yet it is not so obvious to make the difference between a piece of fiction and a poem in free verse or a poem in prose, unless it is, perhaps, that a very short text will tend to be called a poem. There is verse drama and prose drama, and Shakespeare's plays often alternate verse and prose from one scene to the other, or even within one and the same scene, to create certain formal effects. The modernist novelist Virginia Woolf claimed that her novels were ‘poems in prose’. As for the dramatic, one should first be wary that the English word does not have quite the same meaning as the French. Dramatique in French means tragical, that is to say terrible and verging on the tragic. In English, dramatic essentially means ‘of the theatre’, and ‘which pertains to drama.’ A dramatic passage in a novel or a poem is a scene, shown in such a way that it could be staged in a theatre. For this reason, drama (le théâtre) may well be the less ambiguously defined genre, although the cinema has blurred the borderline too, by adapting so many works for the screen. Drama A definition of the dramatic genre has already been touched upon in chapter 3 of this lecture, concerning plot and time, on the occasion of the so-called ‘dramatic’ plot pattern, in which the action rises to a climax and then falls down to a catastrophe and dénouement. The reason for this is that the rules and definitions of the dramatic genre have sometimes been adapted to fiction. The reference text in this respect is once again Aristotle's Poetics, in which the rules of classical drama have been codified. The dramatic genre is divided into two modes–tragedy and comedy. (It should be noted from the start that, in English, tragedy may translate into French as either la tragédie or le tragique, and comedy as either la comédie or le comique, according to the context. The English words tragic and comic are adjectives, as are tragical and comical.) One first distinction has been made between tragedy and comedy in a previous chapter, by saying that tragedy, as opposed to comedy, tended to represent high, or noble, actions and characters. But we shall see that there are also such sub-genres as for instance high and low comedy, and for this reason among others, the definitions should now be pushed a little further. TRAGEDY has famously been defined by Aristotle who said that ‘by representing pity and terror, it 3 [tragedy] operates a purgation [= catharsis] of that sort of emotions’ (49 b 24). For example, in Sophocles' Oedipus King, the spectators feel pity for the young boy with a cruel fate and a cruel father, then terror at the incest he commits without knowing it, but these emotions are eventually evacuated (in a catharsis) by his punishment as he blinds himself and goes into exile. Oedipus King is the classical tragedy par excellence. For example too, in Shakespeare's Richard III, the spectator experiences pity for the victims of the Duke of Gloucester (later King Richard III), terror at his contagiously inhuman behaviour, but these emotions come to a catharsis when the tyrant is killed, and the War of the Roses is put to an end by the marriage of Richmond and Elizabeth which seals the union of the Houses of York and Lancaster. Yet this second example is more problematic than the first, for all the victims of Richard are not innocent, and the spectator tends to be made a moral accomplice to the perversion of Richard, and finally the catharsis is rather put to question by an ending which is to happy to be true. One of the characteristics of tragedy is that it does not have a happy ending, but a catastrophic ending. A comedy is recognised by its happy ending. By definition, a tragedy has a tragic ending, as the tragic hero either dies (like Richard III) or becomes mad (like Oedipus) or even both (like Hamlet). The problem with Richard III, as often with Shakespeare, is that the tragedy is mixed with elements of comedy. For instance, in the dénouement scene, when Richard shouts ‘A horse! My kingdom for a horse!’ it is difficult for the spectator not to smile. Such a hybrid case, like Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice, too, may be called a tragi-comedy. A classical tragedy is either one of the tragedies written by the ancient Greek or Roman playwrights, or a modern tragedy respecting the Aristotelian rules of composition, or even a modern play inspired by Greek or Roman themes. In the Renaissance, and during the Elizabethan era, there developed a fashion for Senecan tragedies, after the manner of the Roman stoic philosopher Seneca. These were sensational plays, with much blood on the stage, and for this reason they were also called bloody tragedies, or tragedies of blood. They had scenes of murder, rapes, insanity, and included supernatural elements like ghosts or witches. These Senecan plays were often Revenge tragedies, with vengeance for main theme. Shakespeare's Hamlet has many elements of the 3 .’… τραγωδια ... δι (1) ελεου και (2) φοβου περαινουσα την των τοιουτωϖ (3) παθηµατων καθαρσιν.’ Where we recognise the etymological root of the words (1) elegy (a poem of mourning), (2) phobia (fear), (3) pathos (excessive emotionality) and the word catharsis. Senecan revenge tragedy, for it is the story of a son avenging his father, with ghosts, murders and madness being represented on the stage. Just as there is high comedy and low comedy, there is a kind of tragedy which is not based on the high deeds of kings and heroes, but on the lives and deaths of ordinary people. Such a play is called a domestic tragedy, as for instance most of the plays of the American playwright Tennessee Williams or of the Englishman Edward Bond. ‘COMEDY,’ said Aris totle, ‘consists in a defect or an ugliness which causes neither pain nor destruction.’ Apart from the fact that comedy tends to represent rather actions and characters of a lower order, there are two key words in its definition–comedy is both entertaining and didactic. By aiming at producing laughter in the audience, comedy first entertains the spectator. But also, it uses wit and humour with a view to having a corrective influence on society, to reform some ideas or attitudes, and to teach some values as against others. Satiric comedy is that type of comedy which uses satire to ridicule personal vices or social absurdities. Satire is not exclusively dramatic of course, and there is satiric poetry and satiric prose. Satiric comedies will tend to favour types or stock characters rather that psychologically rounded characters. A satiric comedy which aims at reforming a particular class of society is called a comedy of manners, because it wields satire against the manners of a given society. It is called a comedy of morals if the target of satire is rather the morals of the time or of a class, as in the case of Tartuffe. In English literature, the Restoration comedies of the late 17th century were typical cases of the comedy of manners. We will come back to the various forms of comedy in a chapter on drama. As far as genre is concerned, there remains to be mentioned a form of comedy which tends to promote some social and moral values against others, but in which humour, wit and laughter are no longer absolutely essential. Those were the sentimental comedies or dramas of sensibility of the early 18th century. They corresponded to what is now called melodrama, that is to say no longer necessarily a musical form of drama, but a comedy in which pathos, strong emotions and romantic feelings prevail. In a melodrama, the spectator finds pleasure in crying rather than in laughing. Sentimental comedy would partly evolve into bourgeois drama, which represented the values of the middle class and had a marked taste for the melodramatic. But all plays are not necessarily either tragedies or comedies, as we have seen in the case of melodrama and bourgeois drama. One important third way is that of Chronicle plays or History plays, which are the predecessors of the period movies (les films en costume.) Many of Shakespeare's plays belong to this category, for they deal with historical subjects and represent the lives of the great men of the past. Historical drama makes use of pageantry, that is to say processions of characters in costume. One of the ancestors of this form of drama was the medieval pageant, a form of street theatre played on an temporary platform which was moved from one place to another between performances. In the Middle Ages, popular forms of drama were the miracle plays or the mystery plays which represented scenes of the liturgy, episodes of the Gospels and of the life of the saints. Among those were the corpus Christi plays, or the cycle plays. Later on, there would be morality plays, of which the characters were allegorical figures of Vices and Virtues, etc.. The most well-known example of a morality is the anonymous play Everyman. Finally, a very short play, with one character, one scene and no plot is called a sketch (une saynette). A succession of scketches is called a Vaudeville (whereas in French the word means rather bourgeois drama). The short dramatic form was much in favour with the theatre of the absurd and such playwrights as Beckett and Pinter. Fiction Such a distinction between the short and the long is one of the ways of beginning an overall classification of prose and the fictional genres. A few points of vocabulary should be made clear from the start– the novel (le roman) is the longer fictional form. The shorter form is the short story (la nouvelle). In between, a longer short story or a shorter novel is called a novella or novelette. When a story tells of events of the past, with exotic adventures in faraway lands and possibly with a touch of fantasy, it is called a tale (un conte). Those are for instance the tales of Sheherazade in the Arabian Nights, or the Tales of the Grotesque and the Arabesque by Edgar Allan Poe. It may also be a philosophical tale as in the case of Voltaire's Candide, or Thomas More's Utopia. When the tale is a cultural heritage, it is a legend. A short tale with a moral is called a fable. William Golding, for instance, the author of The Lord of the Flies, defined himself as a fabulist. But when the prose stops being predominantly fictional, the work becomes and essay. A moralising or polemical essay is a pamphlet. The novel as a genre arose in England in the 18th century. One of its first forms was the epistolary novel, the novel supposedly made of letters which characters wrote to one another. That is the case of Richardson's Pamela, which is also a biography, and even an autobiography, since it is the history of Pamela's life, at least partly written by herself. In so far as it shows the development of the heroine, it could also be called an education novel, a category which would later develop into the novel of apprenticeship or Bildungsroman, in which the main character grows from childhood to adulthood through a series of crises which eventually lead to the elaboration of a philosophy of life. A typical example of the novel of apprenticeship is Dickens' David Copperfield. When the apprenticeship of the hero consists in becoming an artist, one may speak of a Kunstlerroman (from the German word meaning ‘artist.’) That is the case of James Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. One early generic form is the picaresque novel, from the 16th century for of the adventures of a picaro, a poor but clever character who succeeds by his wit rather than his hard work. The typical picaresque novel is Cervantes' Don Quixote. ‘Picaresque’ has become quasi synonymous with the ‘peripatetic,’ for the action of such novels moves from one place to another, so that we discover many different characters on the way, which gives occasions for social satire. Those were the ancestor of the road movie. The fictional dimension may be a mere mask for social reality, with or without an element of caricature or exaggeration as in the case of Dicken's novels. In such a case, we have a realist novel, which may be rather psychological or sociological in its preoccupations. As for comedy, there are novels of manners, of characters, of sensibility, etc.. If real people of real events appear behind fictional names, it is a roman a clef or Schlusselroman. If, on the contrary, the events and characters are far-removed from everyday reality, the novel is a fantasy. The novels of heroic fantasy are set in an imaginary past, just as novels of science-fiction are set in an imaginary future. To be more precise, novels set in the future, without any particular reference to scientific developments, are novels of anticipation. A novel set in an imaginary place is a utopia, from the Greek meaning ‘no-where’, as for instance Samuel Butler's Erehwon or Thomas More's Utopia. When it is a negative utopia, set in an unpleasant place, it may be called a dystopia, as for instance George Orwell's 1984, Aldous Huxley's Brave New World, or Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale. Fantasy should not be mixed up with the fantastic as a sub-genre or a genre. A fantastic novel includes supernatural elements and belongs to a mode of literature which has its origine in the Gothic novel or tales of horror of the late 18th century. Those include Mary Godwin Shelley's Frankenstein and Bram Stoker's Dracula, among many others. Science fiction and the fantastic include some of the masterpieces of literature. But these categories of the fictional genre have also produced a mass of popular literature, which used to be called the dime novel and is now referred to as pulp fiction. The same remark goes for the novel of adventure or novel of action and the detective novel or ‘whodunit’ (le ‘polar’) in which a detective tries to find out who has committed a crime. They are not all quite as good as Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes. This brief presentation of the literary genres and sub-genres is by no means exhaustive, but has only aimed at presenting some key concepts of generic classification. It should not remain a sterile catalogue, but rather serve as a toolbox for more efficient text commentaries. For, most of the time, a given text does not belong strictly to this or that genre, but is rather a hybrid, mixing elements of several generic codes. Being aware of their existence should reinforce our awareness of how these texts are made and how they work when we read them.