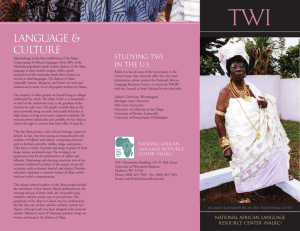

akan indigenous religio-cultural beliefs and environmental

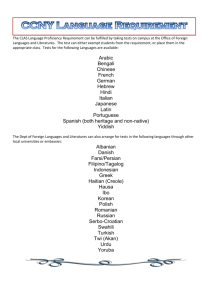

advertisement