lancelot 'capability' brown: a research impact review prepared for

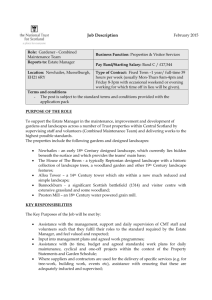

advertisement