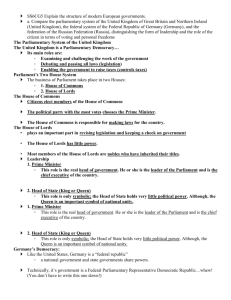

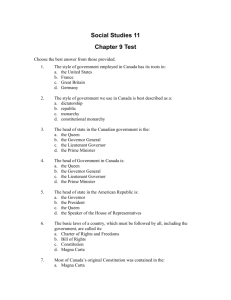

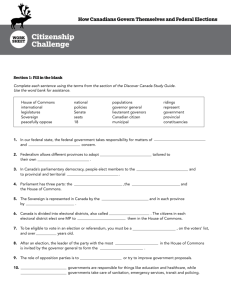

How Canadians Govern Themselves

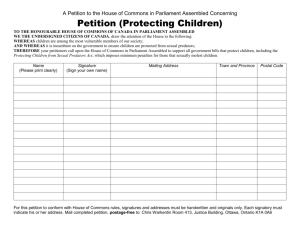

advertisement