The Pound in Your Pocket – Summary Report

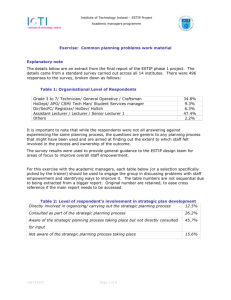

advertisement