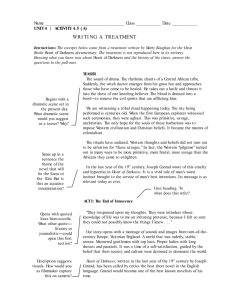

"His Sympathies Were in the Right Place": Heart of

advertisement