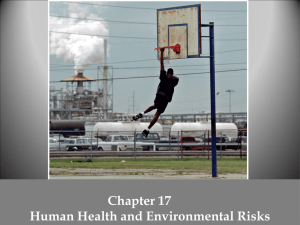

Principles and Approaches of Sustainable Development

advertisement