Principles of Merit Pay - ERI Economic Research Institute

advertisement

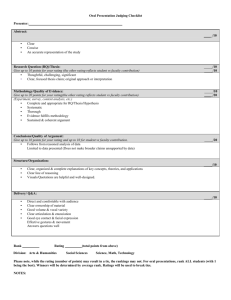

Principles of Merit Pay By Lyle Leritz, Ph.D. Research Manager (800) 627-3697 - info.eri@erieri.com - www.erieri.com Copyright© 2012 ERI Economic Research Institute - 8575 164th Avenue NE, Redmond, WA 98052 A merit program is a form of performance-related pay and is one of the most powerful tools at the disposal of compensation analysts. Performance-related pay traces its roots to psychology and incentive theory. The basic tenet of incentive theory is that people respond to rewards, and organizations can increase performance with the proper motivator. To many of us, this might seem like common sense; however, common sense has not always been at the forefront of compensation systems. Even as late as the early 1900’s, many organizations viewed employees simply as inputs to a process and had little understanding of what might motivate higher performance. A series of breakthrough studies in the mid-1920’s would change that understanding. that individual differences in performance are measurable and important to the organization (typically as they relate to productivity and profit), and that employees have control over their performance. Additionally, the size of the increases must be large enough to warrant the necessary effort to attain them. A trivial increase for top level performance is not likely to be viewed as significant. It should be noted that, in most systems, earned merit increases are a permanent part of an employee’s salary (as opposed to lump sum payments). Finally, it is important that effective communication exists between employees and management and that managers have the requisite tools for administering rewards. Beginning in 1924, George Elton Mayo and his colleagues conducted several experiments at the Hawthorne Works factory in Chicago to study the effect of different working conditions (e.g., lighting, altering break schedules, etc.) on productivity. Initial analyses seemed to indicate that changing the working conditions, indeed, led to changes in productivity. In fact, most changes led to increased productivity, even when that change was reverting to a prior condition from which productivity had also increased. Closer examination led researchers to conclude that productivity changes were not simply due to the changes they were implementing, but were, in fact, due to the increased attention workers were receiving from the researchers. While this did not directly address compensation and performance, it did create a shift in managerial thinking toward the needs and motivations of employees. The benefits of a well-designed merit system include attracting and retaining high performing individuals, as well as motivating employees to increase and maintain productivity. If every employee is rewarded with similar pay increases, there is a risk of high performing employees leaving for an organization that rewards their talent. Alternatively, such employees may stay but lack the motivation to perform at a high level. In either case, an organization is left with moderate performing employees at best. As with any system, there are cons to even well-designed systems. Since many criteria used to measure performance are highly subjective, it can be difficult to objectively evaluate employees. Rewarding individual work in team-based settings can also prove difficult in a merit-based system as individual goals may start to take precedence over team goals. Any negative impact such a system might create should be evaluated and addressed before it is implemented. There are two basic concepts in motivation theory: intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic motivation describes motivation that resides inside an individual and is not based on external rewards. It is observed when an individual engages in an activity for its own sake in the absence of external incentives. Intrinsic motivation is a powerful force; however, it is not typically germane to discussions of merit pay. In contrast, extrinsic motivation refers to factors outside of an individual that motivate performance. These factors include monetary rewards, grades, opportunities, promotions, and so on. Extrinsic factors are not limited to attaining positive rewards, they also include avoidance of negative factors (e.g., fear of punishment). However, it is generally preferable to use positive motivators, especially in an organizational setting. Merit pay is generally considered a positive motivator. Broadly speaking, a merit-based system is designed to reward productive employees with increases in compensation. For a merit-based system to be effective, it is critical Copyright© 2012 ERI Economic Research Institute In addition to individual considerations, there are organizational factors to consider. These factors include, but are not limited to, the cost of measuring performance, organizational culture, managerial-employee relationships (e.g., trust), how competitive an organizations' wages are, pay range width, and the cost of implementing the system. An organization with a distrusting culture and poor linkage between pay and performance is not likely to benefit from a merit-based system. Equally, in an organization that does not pay market competitive wages, employees might view merit rewards as a band-aid on a larger problem (this is not to say they will not work to achieve those rewards, but the long term motivational effects are dubious). Narrow pay ranges can also undermine merit increases. In such a case, high performers will reach the top of a given pay range relatively quickly and be left without room for wage growth. Range width is moderated by increase size, such that larger increases close the gap quicker than smaller increases. 1 The expected tenure for an employee in a given range is an important determinant for how wide the range is and how large increases can be. For example, if employees in entry level positions (which tend to be in narrow ranges) are expected to be promoted to the next range in a relatively short period, then it is acceptable to use large increases for top performers. A 10% increase for high performance would put top performers at the highest end of a 30% pay range in three years. One would expect those performers to be promoted out of that pay range by the time that happened. Such a design is undesirable if promotions are not expected to occur that soon (which is the likely scenario in most situations). On the other hand, small increases can present a different problem. Given a 40% pay range, a 2% increase for high performance would take 10 years for someone just to reach the midpoint from the minimum (assuming they received the highest rating each year). The implicit assumption in the addressed issues is that increases should not put an employee’s compensation above the maximum value specified for the range. Compensation managers use a variety of tools in assessing the relative position of a given employee including compa-ratios and control points. A compa-ratio is simply a ratio of actual pay to the structure midpoint. Specifically, salary is divided by the midpoint value (and typically multiplied by 100 to be expressed as a percentage). Values greater than 100 are above the midpoint; values less than 100 are below the midpoint. Compa-ratios can be used to examine distributions and concentration of wages within a range, as well as make outliers more identifiable. An alternate approach is to use control points in assessing range position. A control point is defined as the point within a given range that indicates a fully-qualified, competent employee. Control points are more flexible than midpoints, in that they are not defined simply by the center of the range; rather, they can be somewhere above or below that. Additionally, control points can be used to establish different “centers” for multiple jobs within the same range. It is fairly common to use control points in broadbanding systems. There are three general types of merit pay systems, performance only being the simplest. In a performance-only system, employees receive increases based exclusively on their performance. Typically, this system is used in conjunction with fixed increase percentages. In particular, all employees with a given performance rating receive the same increase (see Figure 1). The advantages of a performance-only system are they are simple to implement and easily understood. Additionally, employees with the same performance Copyright© 2012 ERI Economic Research Institute Figure 1 Rating Increase 4 5% 3 3% 2 2% 1 0% receive the same increase. There are several disadvantages which make performance-only systems less than ideal. In particular, larger dollar amounts are awarded to people higher in the pay range for the same performance (which can lead to the out-of-range issue previously discussed). Additionally, employees with varying base pay but the same performance receive different actual dollar increases for the same performance. An alternative is to anchor increases to the midpoint (or a control point) of the range. In this system, employees receive increases based on their performance rating and the midpoint of their pay range. See Figure 2 for an example for three employees in a pay range with a midpoint of $1,700 and a performance rating of 3. The advantage of this approach is that it allows high performers in the lower portion of the range to progress more rapidly, while, at the same time, slowing down employees who are above the midpoint. This approach is most often seen with control points and broadbanding systems. While this approach slows down employees who are near the range maximum, it does not have as much control as systems that use both performance and position in range for determining increase amounts. Figure 2 Midpoint: $1,700 Rating: 3 Increase: 3% of midpoint ($51) Employee A B C Current Pay $1,500 $1,900 $1,800 Increase $51 $51 $51 Increase % 3.4% 2.7% 2.8% 2 Two dimensional systems utilizing performance ratings and position in pay range are more flexible and robust than other systems. They are also more complex and difficult to administer. Nonetheless, this is the recommended approach for most compensation programs. Figure 3 presents a simple two dimensional matrix with performance ratings as one dimension and position in range as the other. Notice that the higher an employee is on the pay range, the smaller the available increase (for a given performance level). One of the goals of these systems is to move the pay rates for employees with the same performance ratings toward a common target point (notice in Figure 3 that employees rated at level 2 will not exceed the 3rd percentile unless they improve performance). Additionally, movement is accelerated for high performers who are in the lower portion of the range. Figure 3 Rating 1st Pay Quartile 2nd 3rd 4th 4 9% 7% 5% 3% 3 7% 5% 3% 2% 2 5% 3% 2% 0% 1 2% 0% 0% 0% One major constraint impacting any merit system is the salary increase budget. Budget size is determined by a number of factors including current revenue levels, past budget sizes, and salary increase surveys purchased from various survey firms (e.g., ERI’s Salary Increase Survey). A compensation analyst must set the increases such that the combined cost does not exceed the budget. The more complicated the system, the more difficult it is to hit (or more importantly, to not exceed) that target. There are a number of procedures for assigning increase percentages across performance ratings and position in range. A general model is outlined as follows. The first step is to estimate the percentage of employees that will receive each rating. Rating systems vary where some might be as simple as binary, others might be on a ten point scale (both of those being extreme examples, typical rating scales are between three and five points). There are a number of methods for estimating the number of ratings includCopyright© 2012 ERI Economic Research Institute ing use of past rating distributions, speaking to managers about current employee performance and potential ratings, and reviewing any organizational rules and definitions regarding ratings (for example, a performance appraisal system might dictate that only 10% of employees can receive the highest rating). Once estimates have been established, it is possible to estimate the expected mean performance rating. This is done by multiplying each rating by the expected percentage receiving that rating and summing the results (basically a weighted mean, see Figure 4). Figure 4 Rating 4 3 2 1 Expected Ratio Receiving 0.10 0.45 0.40 0.05 Product 0.40 1.35 0.80 0.05 Expected Mean: 2.6 After a satisfactory distribution of expected ratings is established, it is possible to begin development of a merit increase matrix, with ratings (and associated proportions) as one dimension and actual range distribution breakdowns as the other. The first step is to determine which cell is the most populated, or where the average employee is located, and what increase to assign to that cell (often the best value to start with is the overall budget). Using the starting cell as a base value, the remaining cells are populated based on compensation philosophy (e.g., slow movement beyond the midpoint) and value on rewarding performance (e.g., higher increases for top performers). Unless there is a minimum increase, certain cells should be designated as not receiving an increase (e.g., lowest rating, 4th quartile in range). Further refinements can be made in cases where high performance should outweigh range position. The main focus is to get as close to the salary increase budget as possible. The impact of each cell is calculated by multiplying the percent increase by the proportion in range and again multiplying by the proportion in the rating category. 3 Figure 5 shows a complete matrix using an overall budget of 4%. For example, the cell at the 2nd quartile for a rating of 4 shows a 7% increase, and the cell impact is 0.315 (that is, its contribution to the total budget is 0.315 percentage points). Specifically, the calculation is (7.0 * 0.10 * 0.45). The sum of each cell impact constitutes the total payout. The sum of all the cell payouts in Figure 5 is 3.9%, which is just shy of the 4% budget. Also notice, the simple average of the cell increase values happens to be 4%. This will not always be the case as the cell payout is a weighted average and impacts the actual budget, so the focus should be there. More often than not, initial matrix values will produce a payout that is above or below the budget. In these cases, it is a matter of making modifications to cell values in a trial and error process. While this is only an estimate on the actual payout, coming in slightly under a given budget is typically preferred to going over budget. In particular, it allows for wiggle room with the increases, or alternatively, the potenFigure 5 Pay Quartile (Ratio) Rating (Ratio) 4 (.10) 3 (.45) 2 (.40) 1 (.05) 1st (.28) 2nd (.45) 3rd (.19) 4th (.08) 8.5% 7.0% 5.0% 3.0% 7.0% 4.0% 3.0% 2.0% 4.0% 3.0% 2.0% 0.0% 2.5% 1.5% 0.0% 0.0% Cell Average: Payout: 4.0% 3.9% Copyright© 2012 ERI Economic Research Institute tial for other discretionary rewards (e.g., a one-time bonus for top performers). However, generally the estimated costs should come as close to the budget as possible. The last major component of a merit-based system is the timing of the increases. The two most common methods for granting increases are hire-date and common-date. Hiredate increases are granted based around individual date of employment, while common-date increases grant everyone an increase on the same date. Hire-date timing reduces the financial impact of an organization-wide increase in payroll and tends to spread the administrative impact evenly throughout the year. Additionally, managers are likely to have more time to evaluate each employee. On the other hand, when based on hire-date, performance can be difficult to judge equally across employees as the benchmark is relative and not specific to anything inherent about the organization (e.g., a product cycle). Moreover, calculating and managing salary increase budgets is often more difficult with hire-date systems. Conversely, in a common-date system it is generally easier to project and manage salary increase budgets. Furthermore, the connection between specific business goals, individual performance, and increases is often more apparent to employees in a common-date system. A major disadvantage of hire-date systems is the managerial burden of completing many employee evaluations at one time. Also, some organizations cannot handle a single company-wide increase (often due to cash flow timing). Designing and implementing a merit-based increase program requires care and consideration of many factors. Indeed, as demonstrated at the Hawthorn Works factory nearly a century ago, it is important to understand which factors impact performance behaviors and which rewards are effective at increasing those behaviors. 4