7

WRITING ARGUMENTS

T

he process of writing to persuade begins the moment you,

as a member of a community, feel

an urge to set things straight or to

make your position known.

7a

Making Arguments in Academic Contexts

As a genre defined by social practice, arguments vary in form and content as you move across the curriculum and into new fields of practice.

Conventions of form, for example,

create expectations among readers in

a given academic field that an argument—whether a report of research

findings in the sciences or a literary

interpretation in the humanities—

will proceed in a certain way.

Conventional Forms

The conventional form of an

argument within a discipline serves a

purpose. For instance, a scientific

research report includes certain sections because each one helps persuade

other researchers that the hypothesis

was a good one, the methods of testing it and studying the results were

sound, and the analysis and conclusion are thus worth considering. A research report, when persuasive, will

prompt other researchers to replicate

the study or even to apply its conclusions to solve or explain other problems. Sections 7f and 7g detail two

structures often used in arguments

written in introductory composition.

84

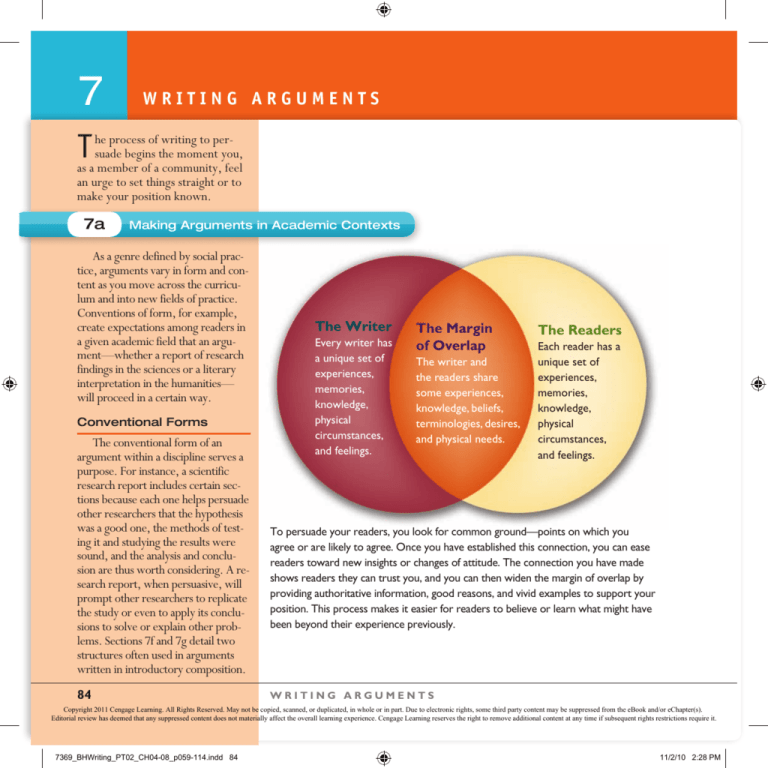

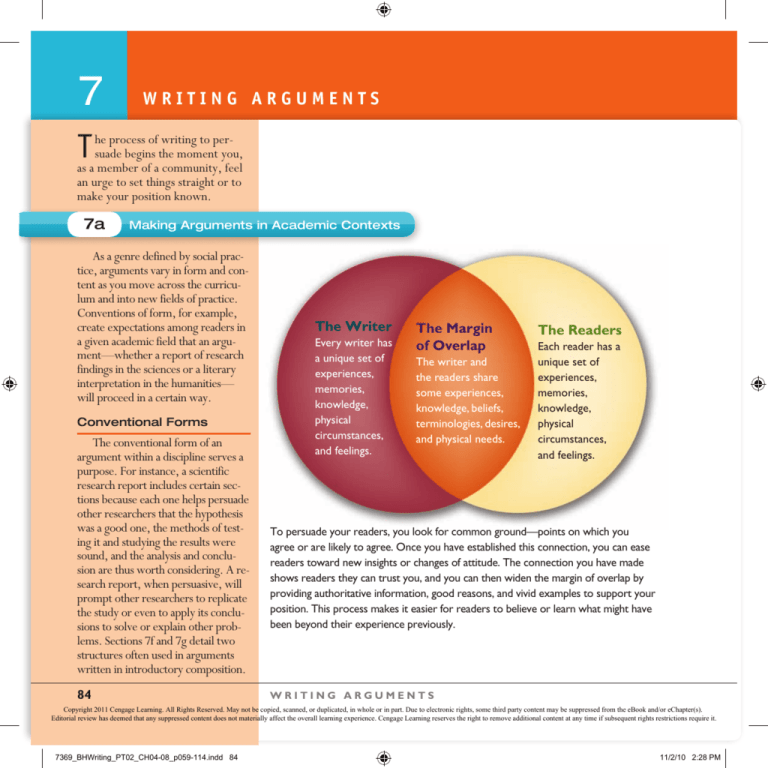

The Writer

Every writer has

a unique set of

experiences,

memories,

knowledge,

physical

circumstances,

and feelings.

The Margin

of Overlap

The writer and

the readers share

some experiences,

knowledge, beliefs,

terminologies, desires,

and physical needs.

The Readers

Each reader has a

unique set of

experiences,

memories,

knowledge,

physical

circumstances,

and feelings.

To persuade your readers, you look for common ground—points on which you

agree or are likely to agree. Once you have established this connection, you can ease

readers toward new insights or changes of attitude. The connection you have made

shows readers they can trust you, and you can then widen the margin of overlap by

providing authoritative information, good reasons, and vivid examples to support your

position. This process makes it easier for readers to believe or learn what might have

been beyond their experience previously.

WRITING ARGUMENTS

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

7369_BHWriting_PT02_CH04-08_p059-114.indd 84

11/2/10 2:28 PM

7a

Identifying Common Ground with Readers

Claim and Support

What does your audience care about? See whether you can find a way to link your

concerns, which they may not have thought about yet, to their existing concerns.

In the academic community, a

successful argument includes a claim

about a contested issue and support

for the claim in the form of good reasons, examples, expert knowledge,

and verbal and visual evidence. A

claim is a position the writer stakes

out in the thesis statement. Most

issues that are considered worth

writing arguments about are disputed; reasonable people disagree

about them. When planning an argument, consider the many sides of a

contested issue and then make smart

and ethical decisions about what

claims to put forth, how to support

them, and how to persuade others

that your point of view is warranted

and desirable.

I want to show my friends that

volunteering for U.S. Public Interest Research

Group (U.S. PIRG) is worthwhile, but they

only seem to be interested in getting their

careers started.

So how will volunteering help them in their careers?

They might . . .

— develop research and presentation skills

that they will be able to use on their jobs.

— be able to promote themselves as people

who follow through to reach important goals.

— show potential employers they are willing to

contribute toward the common good.

Maybe I should argue that they should each choose

an organization to volunteer for, not just promote

PIRG. Since my friends are going to be searching for

different types of jobs, I’ll bet they can each find an

organization particularly suited to their interests.

Choosing a Topic

7b

© Francesco Ridolfi/iStockphoto.com

A good topic for an argument in a

composition class has these important

attributes:

■ It is a contested issue. Reasonable people hold substantially

different opinions about it.

■ It is an issue you care about,

feel invested in, or find intellectually stimulating.

■ It is limited enough in terms of

the amount of research you’ll

need to do and the number of

pages it will take to cover the

topic adequately.

CHOOSING A TOPIC

85

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

7369_BHWriting_PT02_CH04-08_p059-114.indd 85

11/2/10 2:28 PM

7c

Developing a Working Thesis

The thesis statement in an argument is composed of (1) the topic

and (2) your claim about the topic.

The claim is the assertion that your

paper will support with reasons and

evidence. It’s the opinion you develop about the topic as you think

and conduct research.

As you start your project, developing a working thesis statement will

help you learn more about your rhetorical situation and your topic. For

instance, you might think, “Anger

management classes should be required for people who display road

rage.” This idea is your working thesis. As you research the problem of

road rage and some of the solutions

that have been proposed, you may

discover that several states already

have anger management programs in

place. In other states, community

service is seen as a more effective

way to treat those guilty of the

crime. You may decide that community service shouldn’t be associated

with punishment. You decide that

you will argue against community

service as a “penalty” handed out by

courts for a wide variety of minor offenses. You realize, however, that

you will need to propose a way to

encourage community service with a

positive attitude—perhaps by letting

road rage perpetrators choose among

alternatives.

Conventional Forms for Argument Claims

86

WRITING ARGUMENTS

Basic Form

Topic

Examples

Claim

Something should (or shouldn’t)

be done.

Toxic waste disposal needs to be

reconsidered because containers have a

finite lifetime.

Something is good (or bad).

Hackers who expose security flaws in

popular software protect consumers.

Something is true (or false).

Contrary to urban legend, alligators do

not roam the New York City sewers.

Project Checklist

Do You Have an Effective Working Thesis Statement?

❏ Does it indicate that the issue is contestable? Consider which people or

groups of people would not agree with your working thesis. Write down

their objections. If you find at least a couple of substantial objections,

the issue is contestable.

❏ Does it give a sharp focus to the topic? Does it provide a specific claim

and possible reasons and evidence that support that claim?

❏ Does it have the potential to change as new information comes to light

through research? If you can think of how and why it might change,

then your thesis can be deliberated and debated.

❏ Does it help you map out the structure of your argument?

❏ Does it invite more information? Can you clearly see what you would

need to include in order for it to be believable?

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

7369_BHWriting_PT02_CH04-08_p059-114.indd 86

11/2/10 2:28 PM

Understanding Multiple Viewpoints

Identifying Other Perspectives

Think about your working thesis statement. Who would agree with it, who might

agree with it, and who would disagree with it? Why? Divide the possible perspectives into at least two, and preferably more than two, camps. Set up a chart like

the one below to help you keep track of them.

People who agree

would think . . .

People who might agree

would think . . .

People who disagree

would think . . .

Then, using a key term on your topic, conduct an Internet search to find

newspaper or online news source editorials that illustrate these positions. For

example, if you wanted to survey the range of opinion on augmented reality, you

could try these steps:

1. Go to Google News: http://news.google.com.

2. Type “augmented reality” (in quotation marks) in the search box at the top of

the page, and then click on Search News. Your search results will include a

long list of editorials on this topic from various news sources around the

world. You can tell from the title of the page and the brief summary whether

it’s directly related to your topic. Even the first few search results for “augmented reality” reveal a broad range of opinion, with headlines like “Cyborg

Anthropologist,” “Augmented Reality Becomes a Reality,” and “Augmented

Reality: Your World, Enhanced.”

3. Add to your chart a summary of each position or each editorial that looks

helpful. (Be sure to include the citation information.)

4. Analyze an editorial on your topic from each camp, focusing on questions like

these:

■

■

■

■

■

What position does the editorial take?

What evidence or reasons does the editorial provide?

What is at stake in the argument?

Does the editorial address the views of the other side?

What doesn’t the editorial say that it might have said in the interest of arguing

its position more effectively?

UNDERSTANDING MULTIPLE VIEWPOINTS

7d

To write an effective argument

designed to persuade, you need to

develop a keen understanding of the

beliefs of the people opposed to your

position, what arguments they make

to one another, and which arguments

on the other side (your side) they distrust. Consider that there may be

moderate positions somewhere in the

middle.

For example, suppose you believe

that the death penalty is cruel and unusual punishment under any circumstances. If you want to persuade

death penalty advocates of your point

of view, research their views. Visit

the Weekly Standard (http://www

.weeklystandard.com), the conservative, pro–death penalty journal, even

if you prefer the position of the New

Republic (http://www.tnr.com). See

whether you can identify positions

that have qualifications. Research the

positions of people who believe there

should be a moratorium while we

learn more about the issues, such

as the North Carolina Coalition for

a Moratorium (http://www

.ncmoratorium.org). Some people

hold other views—for example, that

the death penalty should not apply to

juveniles or should be used only under extraordinary circumstances.

Your best writing may emerge from

using the evidence that others would

use against you.

87

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

7369_BHWriting_PT02_CH04-08_p059-114.indd 87

11/2/10 2:28 PM

Considering Your Audience and Aims

Writing arguments involves developing, shaping, and presenting

content to an audience for a

reason.

■ Developing: When you develop

an argument, you take your

subject matter into account in

great detail through a process

of invention and inquiry.

■ Shaping: When you shape an argument, you consider audience

and purpose to decide how

much of that content is relevant

or useful.

■ Presenting: When you present

an argument, you consider how

your content should be arranged

and what style, diction, and

tone best convey it to readers.

Effective writers shape and refine subject matter to suit circumstances, which include the opinions

and attitudes of the audience and

the purpose for writing. Your consideration of what your readers already know about the subject, how

they feel about it, and what contrary opinions they hold toward it

should guide every decision you

make as you shape and present

your argument. The aim of your

argument—to change minds, rally

supporters, foster sympathy, and

so on—should likewise guide your

selection, shaping, and presentation of subject matter.

A Comparison of the Audiences and Aims of Argument

88

WRITING ARGUMENTS

People who hold views

different from yours

People who share

your view

To persuade people to

change an attitude or

behavior. Changing

someone’s attitude is

possible only when

knowledge is uncertain

and there are multiple

perspectives.

To reinforce shared

convictions. When people

already agree, the purpose

of argument may be to

turn that agreement into

action—for example,

working to support a

cause. In college classes,

you typically won’t argue

issues on which your

readers already agree.

Instead, find the basis for

disagreement on a subject,

and build an argument

from there.

To inquire into the shades

of meaning in a subject

so that you can open

it up to reflection and

reconsideration. Help

your audience understand

that the subject is more

People who wish to under- complex than they had

stand multiple views

imagined.

Writer’s Specific

Purpose

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

To change people’s

minds and attitudes

To solve problems

To resolve conflict

To build consensus

To create

community

To reinforce belief

To move people

toward

commitment

and action

To foster

identification

To open up a topic

for discussion,

debate, and further

inquiry

To question

common knowledge

To stimulate further

research

© Amanda Rohde/iStockphoto.com

Writer’s General

Purpose

© CREATISTA/Shutterstock.com

Audience

Daniel Korzeniewski/Shutterstock.com

7e

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

7369_BHWriting_PT02_CH04-08_p059-114.indd 88

11/2/10 2:28 PM

Arguing to Inquire: Rogerian Argument

Perspectives

Most topics for argument

naturally lend themselves to

alternative points of view.

The Margin of Overlap

Each perspective shares some

common premises with the others.

Rogerian Argument

The aim is to broaden the

margin of overlap among

positions by fairly representing

multiple sides of an issue,

creating the opportunity for

finding common ground.

Rogerian argument acknowledges and accommodates alternative positions and

perspectives. The purpose is not so much to settle an issue as to map the various

positions that reasonable people might hold. Throughout a Rogerian argument,

the writer emphasizes common ground, attempts to be objective and truthful

about the alternative perspectives, and concedes the relevance of other points of

view. The argument often provides background or context, in the hope that

enlarging the frame of the argument will make it easier for the various disputants

to find common ground. Rogerian argument is particularly useful when your

audience is hostile.

ARGUING TO INQUIRE: ROGERIAN ARGUMENT

7f

Often an either/or argument

not only presumes an issue has only

two sides but also shows the

amount of force holding people

apart in the world. Sometimes people in ongoing debates and arguments become so defensive that

they cannot even see the humanity

of the people with whom they are

arguing.

Arguing to inquire involves arguing ethically and intelligently in

order to build grounds for consensus. One form of arguing to inquire

is Rogerian argument, a method

developed by psychologist Carl

Rogers (1902–1987). The goal of

Rogerian argument is to find as

much common ground as possible

so that parties in the debate or argument will see many aspects of

the issue similarly. Believing that

shared views of the world create

more harmonious conditions,

Rogers hoped that people would

hold enough in common that they

could be persuaded, through debate and dialogue, to allow differences to coexist peacefully.

Rogerian argument seeks to resolve

conflict by expanding the margin of

overlap between people.

89

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

7369_BHWriting_PT02_CH04-08_p059-114.indd 89

11/2/10 2:28 PM

7g

Arguing to Persuade: The Classical Form

Aristotle described rhetoric as

the art of finding the available means

of persuasion in any particular case.

This means, simply, that a speaker

or writer needs to know what arguments to use and the best way to

present them. Aristotle spent most

of his time trying to identify how to

invent arguments and how to determine their potential usefulness.

Cicero, a Latin rhetorician, later described a generic form for the classical argument.

The classical form rests on the

theory that we change our minds

and come to believe in something

new in a predictable pattern. First

something needs to capture our attention. Then we need to learn

more about it, analyze it, consider

what others say about it, and

interpret it.

The Classical Form of Argument

■

■

■

■

■

■

90

Introduction. The introduction puts the reader in the right frame of mind and

suggests, “Here comes something important.” It might tell a story that illustrates

the controversy or the need to resolve it.

Narration. The narration provides background information necessary for understanding the issue or tells a story that makes a comparison, discredits opponents’ views, or just entertains the audience. It often includes cited research

and references to what other people have said about the topic in the past.

Partition. The partition lists the points to be proven or divides the points into

those agreed on and those in dispute. It is usually very brief, sometimes only a

few sentences if the essay is short.

Confirmation. The confirmation is the proof and thus argues the case, thesis,

or main point of contention. It may include evidence, examples, and quotations

from authoritative sources. Each premise or assumption may be unpacked, explained, and argued using deductive reasoning (arguing from accepted fact to

implications) or inductive reasoning (arguing from examples). The confirmation

takes up each of the points listed in the partition or implied in the thesis or

controlling idea.

Refutation. The refutation takes the other side or sides and shows why they

don’t hold. It may dispute the positions of opponents, using anticipated or actual arguments; cite claims of inadmissible premises, unwarranted conclusions,

or invalid forms of argument; or cite stronger arguments that nevertheless apply only in unrealistic circumstances. The refutation should address the most

likely counterarguments, treating them fairly and accurately so as not to arouse

the indignation of the audience.

Conclusion. The conclusion sums up or enumerates the points of the argument; it may appeal to the emotions of the readers, encouraging them to feel

motivated to change attitudes and sometimes to feel resentful of opposing

viewpoints or sympathetic to the writer’s position. The conclusion should help

people understand the significance of the issue and the importance of viewing it

as the writer proposes. The conclusion may also rouse the audience to action

or make a specific recommendation.

WRITING ARGUMENTS

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

7369_BHWriting_PT02_CH04-08_p059-114.indd 90

11/2/10 2:28 PM

Supporting Your Claim

Project Checklist

Motivating Your Readers

7h

An effective argument includes

reasons and evidence in support of

the points you are asking readers to

accept. Organized logically and

presented persuasively, the reasons

and evidence you provide make

your case.

How can you motivate your readers to identify with your position and

change their actions or attitudes?

Research Your Topic

❏ Consider the kinds of evidence that your audience will find

persuasive. Suppose you are against hunting animals for sport.

Claiming that all animals should have the same rights as humans might

not be persuasive with hunters, who might see their rights under the

Constitution as superseding those of animals. Rather, you might suggest

alternative sports that provide the same kind of satisfaction as hunting

or demonstrate that, because of accidents and hunter-on-hunter

violence, hunting is more dangerous to humans than to animals. You

will need to include evidence that helps hunters see that it is in their

best interest to try something else.

❏ Treat your readers as intelligent and reasonable people, even if you

think their positions are wrong. Suppose you want to advance the

cause of Students Against Drunk Driving. Saying that social drinkers are

“incapable of knowing what is best for them” or calling them “future

alcoholics” is likely to cause them to ignore the logic of your appeal.

❏ Tell readers why they should consider your position, and be direct

about what you want them to do or think. What difference does it

make if readers agree with you? What exactly should they take away

from your argument? What do you want readers to do? How should they

see the subject differently now?

❏ Make the case for why the issue is important now. Readers will want

to feel some urgency. What difference does it make if they believe you

now rather than later (or never)? What will happen if the situation is

not resolved?

Find the background information

and facts you can share with readers

so that they will judge your argument

as reasonable. It’s smart to know

more about your subject matter than

your audience does so that you can

shape their responses to it.

SUPPORTING YOUR CLAIM

Define Terms to

Establish Common

Ground

Defining the terms you will use in

your argument is crucial because it

helps you establish common ground

with your readers. You can use this

consensus to develop definitions in a

way that supports your point of view.

Use Evidence Effectively

Verifiable facts and widely accepted truths are almost always the

most effective kinds of support.

91

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

7369_BHWriting_PT02_CH04-08_p059-114.indd 91

11/2/10 2:28 PM

7h

Distinguish Fact from Opinion

When you gather evidence for your

arguments, it is helpful to distinguish

between fact and opinion. Facts will

usually be more persuasive if your

audience is fair-minded. The opinions of others don’t prove an argument’s claims, but they do show that

others have come to similar conclusions, making your argument more

believable.

Fact vs. Opinion

Prevention of Art Theft

The biggest art heist in history occurred in Boston in 1990, when

thirteen pieces of art, including three Rembrandts, a Manet, a

Vermeer, and five Degas drawings, were stolen from the Isabella

Stewart Gardner Museum. (“The Gardner Heist,” by Stephen

Kurkjian, Boston Globe at boston.com, Globe Special Report,

March 13, 2005, accessed March 13, 2005.)

Draw on Expert Testimony

and Authoritative Sources

Cite the opinions of those who have

expert knowledge of the subject matter because they have published

books or articles on the subject, have

studied it professionally, or have

some other insight not shared by the

general population. Knowledge that

has been reviewed and edited by experts has an air of authority that can

give added weight to a case.

Be Careful When Using Personal

or Anecdotal Experience

A few personal experiences, no matter how poignant, are not enough

support for an argument. You can

certainly recount personal experiences, but base your argument

mainly on statistics and other

evidence.

A fact is a statement whose truth can be verified by observation,

experimentation, or research.

Prevention of Art Theft

Museums should do their best to prevent art theft, but if

they cannot prevent it, they should be financially prepared

to replace stolen art with art of similarly high quality when

necessary.

An opinion is an interpretation of evidence or experience.

92

WRITING ARGUMENTS

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

7369_BHWriting_PT02_CH04-08_p059-114.indd 92

11/2/10 2:29 PM

Appealing to Readers

Project Checklist

Questions to Ask about Your Reasoning

Ask these general questions about your reasoning. Refer to pages 158

and 167 for more information on evaluating research sources for

comprehensiveness, reliability, and relevance.

❏ Have you supplied sufficient evidence to be convincing without

boring your readers? Evidence is sufficient when it proves your

argument but doesn’t pile on unnecessary information that might

distract readers from your point(s).

❏ Is the evidence you cite reliable and accurate? Can you confirm

that the information is correct by finding it mentioned in other

sources?

❏ Are the experts you cite in support of your argument knowledgeable,

authoritative, and trustworthy?

❏ Are your examples relevant, sufficiently developed, and interesting?

❏ Does your argument proceed by sound logic? Have you avoided making

logical fallacies ( page 96)?

If your argument is based on examples, also ask

❏ Do the examples show what you say they do?

❏ Are the examples familiar or obscure? Are they memorable? Why?

❏ Have you used a sufficient number of examples to make your point,

but not so many that you bore or insult your reader?

❏ Do you explain clearly what your examples prove or illustrate?

If your argument moves from general to specific, also ask

❏ Will readers agree with your premises? If not, should you explain

them?

❏ Is it clear how your conclusion follows from your premises?

❏ Are there any other conclusions to be drawn from your premises?

Should you mention them?

APPEALING TO READERS

7i

When you write an argument,

you can make three general kinds

of appeals to readers.

■ Logos is the appeal to reason.

■ Ethos is the writer’s presentation of herself or himself as

fair-minded and trustworthy.

■ Pathos is the appeal to

the emotions of the audience.

Logos: The Appeal

to Reason

Logos should be the focus of an

academic argument.

Induction: Reasoning from

Examples to Conclusions

Induction is the process of reasoning from experience, gaining insight

from the signs and examples around

us. Induction relies on examples to

support or justify conclusions. The

most important consideration with

induction is to make sure that the

examples support the conclusions—

that they “exemplify” the case in the

reader’s mind. When the examples

are valid and vivid, an inductive argument can be persuasive if you have

properly gauged the rhetorical

situation.

Deduction: Reasoning from

General to Specific

In deduction, you argue from established premises, or truths about

general cases, toward conclusions

93

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

7369_BHWriting_PT02_CH04-08_p059-114.indd 93

11/2/10 2:29 PM

7i

in more specific circumstances

(“Given A, then B and C must follow”). A deductive pattern uses

a syllogism or an enthymeme to

draw a conclusion.

A syllogism is a form of logic

that has a generalization (or major

premise), a qualifier (or minor

premise), and a conclusion. A syllogism starts with true statements

from general cases and applies

them to specific cases.

An enthymeme, which we

have been calling a claim, suppresses one or more premises because the audience is likely to accept them.

Sample Syllogism

Generalization (major premise): All curious people enjoy learning.

Qualifier (minor premise):

You are a curious person.

Conclusion:

Therefore, you will enjoy learning.

Sample Enthymemes

Minor premise

Conclusion

1. I’m a curious person, so I enjoy learning new things.

Major premise

Conclusion

2. Curious people enjoy learning, so I do, too.

Ethos: The Appeal

of Being Trustworthy

Readers will look to see if the

writer is someone they can trust. As

a writer, you cultivate trust by showing readers that you know what you

are talking about, have carefully considered the evidence and other perspectives on the issue, and have the

audience’s best interests at heart.

Pathos: The Appeal

to Emotions

In most academic writing, you

won’t need to appeal to the emotions

of your readers. However, emotion

is naturally a factor when people are

deciding whether to take action or

change their attitudes.

94

Project Checklist

Questions to Ask about Ethos and Pathos

❏ Have you demonstrated to your audience that you know your subject

thoroughly?

❏ Do your citations of outside sources help your ethos? (Be careful that

you don’t let the voices of others overpower your own authority.)

❏ Have you represented opposing viewpoints fairly?

❏ What tone (attitude toward the subject matter) do you want to convey?

❏ Does the presentation of your text—in print, on the Web, by email or

letter, etc.—help convey that you have been mindful of the reader’s

context?

❏ How will your audience feel about the subject?

❏ Should you acknowledge your readers’ feelings directly?

❏ Should you convey to your readers how you feel about the subject?

Would doing so help or hurt your argument?

❏ Should you structure your argument any differently because your

audience is likely to have a strong emotional response to the topic?

❏ What do you want people to feel when they have finished reading?

WRITING ARGUMENTS

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

7369_BHWriting_PT02_CH04-08_p059-114.indd 94

11/2/10 2:29 PM

Analyzing Your Argument Using the Toulmin Method

Sample Toulmin Analysis

In your reading and research, you learn

The U.S. government wants to spend billions of dollars to send people to the moon,

once again, for the purposes of building a permanent colony there for scientific research

and in preparation for sending astronauts to Mars. The government has also been slow to

respond to the crisis of global warming.

Data

So you claim

NASA’s inability to rectify the technical problems with the Space Shuttle after the Columbia

disaster demonstrates that it is foolish to waste money on new ventures and divert taxpayer

dollars from more pressing scientific problems like global warming.

Claim

Then you ask: What are some of the warrants that support the claim?

NASA has not fixed technical problems in the past.

If you can’t fix old problems, you shouldn’t create new ones.

Global warming is a more important issue than space exploration.

Warrants

What are the less obvious warrants—ones that rest on value, belief, or ideology?

Space exploration cannot help us solve problems like global warming.

Discovery and adventure are overrated goals.

Global warming is a problem that needs to and can be addressed effectively. Warrants

You may decide that you need backing for at least one of your warrants:

Al Gore’s film An Inconvenient Truth confronts global warming nay-sayers by showing indisputably that the phenomenon is already negatively affecting global agricultural production.

Recent agreements among world leaders for limiting harmful emissions would still yield a

3 degree Celsius warming worldwide, according to a study by the United Nations. Backing

And you must address a rebuttal that challenges one of your warrants, the belief that

discovery and exploration always stimulate new knowledge and economic benefits:

7j

The persuasiveness of your argument depends on a wide variety

of factors: the willingness of your

audience to assent and their motives for doing so, the common

ground you establish, the effectiveness of your rhetorical appeals,

and the context that defines all of

these factors. Philosopher and

rhetorician Stephen Toulmin recognized the importance of context

in evaluating persuasion. He also

developed a method for analyzing

and mapping the structure and

logic of persuasive arguments,

what he called their progression

(where an argument starts and

how it unfolds). Writers can use

the Toulmin method to analyze

their own arguments or those of

others.

Arguments proceed from data

or grounds (facts, evidence, or

reasons) that support a claim

(a point of contention, a position

on a controversial issue, a call to

act, a thesis). Claims are based on

warrants, the unstated premises

that support a claim. Warrants require backing (support, additional data) when they are disputable. Qualifiers (terms like some,

most, or many) may be used to

soften the claim. Rebuttals, or

challenges to the claim, focus on

points that undermine the claim or

invalidate the warrant.

The pursuit of phlogiston showed that scientific exploration without clearly defined goals

may siphon valuable money and attention from worthier pursuits.

Rebuttal

Qualifier

ANALYZING ARGUMENT USING TOULMIN METHOD

95

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

7369_BHWriting_PT02_CH04-08_p059-114.indd 95

11/2/10 2:29 PM

7k

Identifying Fallacies

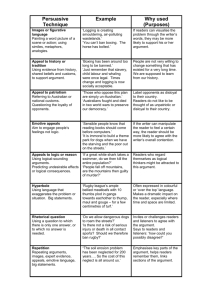

A fallacy is an error in reasoning, whether deliberate or inadvertent. You can use your knowledge

of fallacies to expose the problems

in reading material, and you should

check for fallacies in your own

writing. Fallacies of relevance work

by inviting readers to attach to a

claim qualities that are not relevant

to the subject. Fallacies of relevance bring unrelated evidence or

information to bear on issues that

are outside the scope of the subject

matter or that have little or no

bearing on our judgment of a case

in its own right. Fallacies of ambiguity include ambiguous or unclear

terms in the claim. Fallacies of ambiguity presume that something is

certain or commonsensical when

multiple viewpoints are possible.

For more on fallacies, visit The

Writing Center of the University

of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

(http://www.unc.edu/depts/

wcweb/handouts/fallacies.html).

Fallacies of Relevance

1. Personal attack (ad hominem). Discrediting the person making the argument to avoid addressing the argument

2. Jumping on the bandwagon (ad populum). Arguing that something

must be true or good because a lot of other people believe it

3. Nothing suggests otherwise . . . (ad ignorantiam). Claiming that something is true simply because there is no contrary evidence

4. False authority (ad vericundiam). Suggesting that a person has authority

simply because of fame or notoriety

5. Appeal to tradition. Claiming that just because something has been so

previously, it is justified or should remain unchanged

6. The newer, the better (theory of the new premise). Claiming that

because the evidence is new, it is the best explanation

Fallacies of Ambiguity

7. Hasty generalization. Making a claim about a wide class of subjects based

on limited evidence

8. Begging the question. Basing the conclusion on premises or claims that

lack important information or qualification

9. Guilt by association. Claiming that the quality of one thing sticks to another by virtue of a loose association

10. Circular argument. Concluding from premises that are related to the

conclusion

11. “After this, therefore because of this” (post hoc, ergo propter hoc).

Assuming that because one thing followed another, the first caused the

second

12. Slippery slope. Arguing that if one thing occurs, something worse and

unrelated will follow by necessity (one stride up the slippery slope will

take you two steps back)

96

WRITING ARGUMENTS

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

7369_BHWriting_PT02_CH04-08_p059-114.indd 96

11/2/10 2:29 PM

Conceding and Refuting Other Viewpoints

Contending with Readers’ Perspectives

Two methods exist for contending with readers with hostile or differing perspectives.

■

■

You can demolish their arguments viciously (as many argument writers do

when posting unmoderated comments on blogs).

You can anticipate their objections and refute them tactfully.

Where to Place Your Refutation

You should place your refutation at the spot in your argument where it will do

the most good. If your readers are likely to have a refuting point in the forefront

of their minds, then you need to address that opposing issue earlier rather than

later. The longer you put off dealing directly with the likely objections of readers,

the longer you postpone their possible agreement with your position. If there are

important contrary views that your readers might not have made up their minds

about, then your refutation will likely work best later in your essay. The important

principle to remember is that effective writers raise issues (as in a refutation) at

the opportune moment—just when readers expect them to be discussed.

i Guidance for arguing on essay exams can be found at www.cengagebrain.com

7l

When you concede, you give credence to an opposing or alternative

perspective; you grant that some

members of your audience might

disagree with you and agree with

another’s point. When you refute,

you examine an opposing or alternative point or perspective and

demonstrate why it is incorrect or

not the best response or solution.

If you address possible objections in a fair-minded but direct

way, you increase the likelihood

that the opposition will understand

and be won over to your position.

Fair-mindedness will also enhance

your ethos with neutral readers,

who will consider you a reliable

and trustworthy source.

A Student’s Proposal Argument

7m

Holly Snider

Using Technology in the Liberal Arts: A Proposal for

Bridging the Digital Divide

Many students at Lincoln University (LU) are struggling to overcome

the lingering effects of the technological divide that separates prepared

students from under-prepared students. A historically black college, LU

explains in its Mission Statement that applications are particularly sought

from “descendents of those historically denied the liberation of learning”

(“University Mission Statement”). Given the equalizing mission of the

University, it is surprising that—for students who plan to be English Liberal

Arts majors—few measures are in place to address disadvantages stemming

from unequal access to technology. The tools of LU’s English classrooms are

A STUDENT’S PROPOSAL ARGUMENT

General statement about the

nature of the problem.

Specific statement about the

problem and those it affects.

97

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

7369_BHWriting_PT02_CH04-08_p059-114.indd 97

11/2/10 2:29 PM

7m

Holly cites unequal access to

classroom technologies across

disciplines, which perpetuates

the digital divide.

The proposal for change comes in

the second paragraph, after the

nature of the problem has been

described.

This paragraph argues for wider use

of existing classroom technologies

and (by implication perhaps) faculty training.

Holly refutes one possible

objection.

This paragraph proposes that teachers use online resources to supplement their teaching.

98

pen and paper, print books and journals. Compare that to a classroom in

Mass Communications, a discipline that shares an academic department

with English here at Lincoln. In those classes, students work in modern Mac

labs, using state-of-the-art hardware and software. They collaborate on

projects easily and efficiently, using the tools of professionals in the field.

Additionally, Mass Communication majors who follow the Broadcast and

Radio tracks regularly use the modern radio and television studios, which

are located in the student union building. In classes that have traditional

Liberal Arts majors mixed in with Mass Communications majors, it is clear

that the Mass Communications students have more experience with and are

more savvy about computer-based learning.

Traditional Liberal Arts majors deserve to be just as prepared to

succeed in the digital world as any other student. Instead of letting Mass

Communications be the technological leader in the department, the

English Liberal Arts program should embrace the potential that exists in

a digitally adapted classroom.

Classrooms at Lincoln have now been equipped with “Smart Boards,”

which are among the most current media for instruction in classes today.

Most people have seen Smart Boards on the Weather Channel: they are touchsensitive, much like the newest generation of cell phones, and they can store

information in a central location so that a faculty member’s desktop computer

is now only one of many workstations that lesson plans can be created and

stored in for use in the classroom Smart Board. Many instructors seem to want

to ignore the new technology in the classroom, making little use of it. Rather

than use the Smart Boards, faculty stick to an obsolete version of WebCT.

Maybe these instructors worry that any gains in technological literacy must

come at the expense of the stated goal of the English major at Lincoln: “the

study of English and American literature and language” (“English Liberal

Arts”). But faculty should consider that digital innovations in the classroom

could offer a refreshing approach to literature—while providing a bridge to

those students on the other end of the digital divide.

Many ideas for incorporating interactive technology into traditional

lesson plans can actually be found online. For instance, an online teaching

resource called Teaching English with Technology offers a technological

supplement for teaching Sandra Cisneros’s wonderful book The House on

Mango Street, which many of my fellow students had a hard time

understanding. Mary Scott, a public school teacher from Oakland,

California, explains how technology supplements the instruction of

WRITING ARGUMENTS

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

7369_BHWriting_PT02_CH04-08_p059-114.indd 98

11/2/10 2:29 PM

7m

this traditional literary book: the goal of the lesson is “to explore Human

Rights issues and teach simple writing skills for the creation of an

autobiographical book about their Human Rights and own cultural

experiences. The final product is a book comprised of the students’ essays.

The technology skills learned include computer graphics, clip art, and

formatting. [Students] also learn how to bind the materials into a book.”

The same site provides links to videos featuring Sandra Cisneros reading

from the novel and to projects created by students. This approach to

teaching an appreciation for literature combines many aspects of the

traditional instruction found at Lincoln, and it also uses the technological

improvements that the University has seen over the last two or three

years. Not only does this approach to teaching literature create excitement

among students reading the book for the first time; it also helps them

sharpen their computer skills. Similar technological approaches to

teaching literature could be devised without changing the literary

curriculum that makes Lincoln’s major so valuable.

The value of an English degree at Lincoln University is in its mixture

of traditional text-based learning and technological innovations in writing

and publishing. Like their colleagues in Mass Communications, English

professors should prepare their students for writing in a technology-rich

world, making sure to incorporate technology as much as possible while

reminding students that their own literary abilities will always reign

superior over the technology. By using class time to help students research

online, participate in online discussions, and show students how to use

online resources to continue their education, teachers would promote an

overall education that embraces the best of both the old and the new.

There are numerous ways to incorporate technology into the core

curriculum of the English Liberal Arts program. Indeed, the program has a

key role to play in helping bridge the digital divide.

Works Cited

“English Liberal Arts.” English and Mass Communications Department Home. Lincoln

University of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, n.d. Web. 12 Apr. 2010.

Scott, Mary. “Lesson Plan by M. Scott.” Teaching English with Technology.

EdTechTeacher, n.d. Web. 10 Apr. 2010.

“University Mission Statement.” President’s Information Exchange. Lincoln University of

the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 15 Apr. 2000. Web. 12 Apr. 2010.

A STUDENT’S PROPOSAL ARGUMENT

Holly offers specific details regarding one solution, which involves

students using new technologies

to produce collections of student

work, helping them learn

computing skills.

The closing paragraph reiterates

that teachers should encourage students to use new technologies in

creative ways that can also enhance

learning. By doing so, they can give

students in all majors a rich experience and equal access.

Holly draws from the university’s

own mission statements, an effective way to remind readers of

shared goals.

99

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

7369_BHWriting_PT02_CH04-08_p059-114.indd 99

11/2/10 2:29 PM