University of Washington: The Evolution of Criminal Law and Police

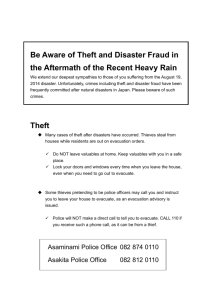

advertisement