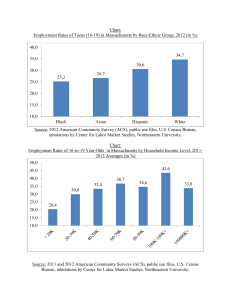

The American Community Survey

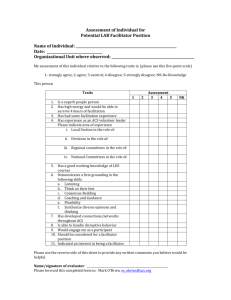

advertisement