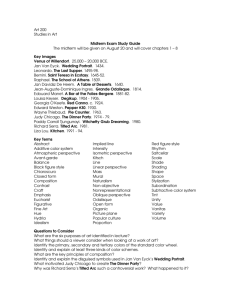

THE DIALECTICAL CONSTRUCTION Modern art & architecture in

advertisement