Warehouse and Distribution Centre: How

to go greenfield

By Maida Napolitano, Contributing Editor -- 9/1/2007

•

•

•

•

Why Go Greenfield?

Steps To Implement

21 Tips for a successful greenfield project

Gantt chart PDF

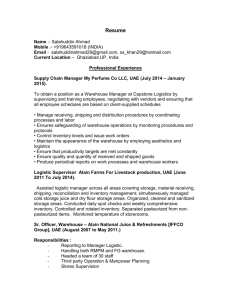

Over the past 10 years, my colleague, Bill Elenbark, and I have worked together on a number

of greenfield projects with a wide variety of clients for Gross & Associates, a consulting firm

based in Woodbridge, N.J. Together, we’ve christened many brand-new facilities, sited them

in better locations with improved layouts, more efficient equipment and a whole lot more of

space. We both agree that the key to success is in the planning and scheduling details—

beware of the manager who can’t be bothered by them.

Now a senior engineering consultant for the company, Elenbark’s expertise lies in distribution

network modeling and determining the location of a new warehouse, while I’ve been mostly

involved with new facility design and implementation. In this article, which includes insight

from two of our top greenfield clients, I’ll relate all of the process steps Bill and I go through

when locating, designing, planning, and implementing a new DC. In turn, logistics

professionals can get a better feel for what needs to be accomplished if a greenfield project is

in the plans.

Why Go Greenfield?

According to Elenbark, clients come to us because they’ve run out of space at their existing

facilities and they simply can’t expand. Another reason may be due to a new, expanded

business strategy or plan. “In an acquisition, for example, companies can have too much

space or redundant facility locations,” he says. “They may want to consolidate operations into

a new facility located optimally to serve customers of both companies while reducing

transportation costs.”

“Our biggest motivator was anticipated growth throughout the Western United States,” says

Rita Hoffman, vice president of operations for Murray Feiss, a Generation Brands Company

that makes and distributes high-end lighting and home décor. “We also wanted to reduce our

import time from Asia and cut in half the freight time to our West Coast-based customers.” To

do this, Hoffman oversaw a 207,000 square-foot greenfield DC project in Las Vegas in

February 2005.

Emile Lemay, vice president of North American Wholesale Operations for the Luxottica

Group, has worked on greenfield DCs for a few companies in his extensive distribution

career. “Most companies try to work with what they have for as long as possible, or until their

current infrastructure can no longer service their needs,” says Lemay. “This breakdown may

be 'physical’ in that low ceilings prevent the full use of cube, or 'operational’ where labor and

utility costs keeps increasing in that existing location.”

While new facilities can certainly be a terrific long-term investment, their installation and

implementation shouldn’t be taken lightly. The details that must be considered are extensive.

Over the next few pages, however, I’ve overviewed the most important steps in an effort to

help illustrate just how elaborate the process can be.

Step 1: Secure top-management commitment and a project budget. “One of the hardest

things to do if you’re a logistics manager is to make a convincing argument for the new

space,” says Lemay. Once the pitch is made, you need to organize your resources by putting

together a well-qualified and competent project team with an eye for detail. You’ll also want to

establish a plan of action by identifying the immediate high-level steps to follow.

1

To maintain objectivity and reduce pressure on the project team, present your plan before any

major crisis needs to be averted. Lemay suggests not waiting until you are literally out of

space. Provide a clear vision of the project’s expected deliverables, specifically the savings

and efficiencies gained with a new facility. But most importantly, specify a budget and have

management sign off on it.

Step 2: Determine the best geographic area for your new project. Finding the actual

greenfield to locate your project may not be intuitive. With multiple suppliers, coast-to-coast

customers, and other DCs, this one step can get extremely complicated.

However, using software to model the network not only simplifies matters, but also allows

managers to test different what-if scenarios for locating in one state versus another. “Today’s

network-modeling software can process all customer locations by zip code, including existing

inbound and outbound shipment methods and corresponding costs, existing source points

and warehouse locations, and current warehouse rates,” explains Elenbark. This data is then

validated against the existing distribution network.

Forecasts and other planned distribution strategies are then entered into the model, and

various options are tested. At the end of the study, an ideal distribution network plan is

suggested and an optimum geographic area is recommended. The program also provides

final product and customer allocation among warehouses, which in turn determines the new

facility’s capacity and size.

Step 3: Design a prototype facility. You’ll need to audit the existing operation and look for

ways to improve storage density, productivity, and order cycle time. By gathering this key data

you’ll be able to apply the appropriate forecasts to span the number of years you plan to stay

in the new facility.

You’ll also need to analyze quantitative data and create inventory and movement profiles of

SKUs. This allows you to identify SKU categories and determine the best ways to store and

move each category. For each aspect of the operation, generate alternatives and evaluate

them quantitatively and qualitatively. You can then select the plan with the best technological

and operational fit with the best return on investment—drafting software such as AutoCAD

helps speed the design and facility planning process.

Step 4: Select the best site in the geographic area. Armed with the prototype facility, it’s

time to select candidate building sites. “The network model can only provide a location

specific to a three digit zip code,” explains Elenbark. “There are usually cost savings to be

achieved within that zip code or its surrounding area.” The area defined by the three digit zip

code can be immense: One end of the area may have overly strict building codes while

another end may be more lenient. For one of our clients, we found that if they opened a new

warehouse 50 miles from the recommended zip code, they would save at least $100,000 in

pallet rack costs because of that town’s less stringent seismic requirements.

The dynamics involved in evaluating site selection are considerable. Key factors include labor

cost and availability; state and local taxes; zoning restrictions; insurance rates; utility rates;

and accessibility to interstate highways. First, identify the factors that most concern your

operation then work in concert with a commercial realtor to establish whether to lease or

purchase, build on greenfield land, or modify an already existing facility to suit your needs.

It’s also important to develop a matrix of pros and cons along with specific costs. Hoffman

says her team performed a detailed cost analysis to decide between Los Angeles and Las

Vegas. In the end, the difference in costs was negligible, so it came down to what she calls

“emotional issues.”

“The concept of being a big fish in a little pond, as opposed to L.A. where you are a little fish

in a big pond, was attractive to us,” explains Hoffmann. In the end, she says, Las Vegas had

a more business-friendly atmosphere. Local authorities, vendors and suppliers were eager to

2

work closely with her in all areas such as purchasing pallets, finding transportation, and

acquiring temporary office space.

Step 5: Finalize layout in the selected site and begin construction. In this step, you need

to make your design fit into the selected site’s specific parameters. Once completed, you can

begin creating detailed performance specifications for the building and all the equipment.

It’s important to work with local business authorities as well as the people operating

warehouses to get in touch with reputable contractors and equipment suppliers. You can then

send performance specifications out for bids and select contractors. Lemay says that he had

the assistance of a local commercial developer to help build a new warehouse to suit, which

was a terrific help. If an existing building is used, you may still need to hire contractors to

demolish and reconstruct areas of the facility to best suit your needs.

But most of all, stay on top of construction schedules, inspect the building, and confirm that it

is being built as planned. Contractors and architects are typically in charge of dealing with

building permits and inspections, but keep updated on construction developments and resolve

any delays.

Step 6: Implement. Put together an implementation team from operations, facilities, and IT.

Include representatives from contractors and equipment suppliers, engineers, and architects.

This team should be headed by an implementation coordinator.

At this stage it’s critical to develop a plan outlining every detail needed for the move into your

new facility. Use a scheduling tool to create and update the schedule, assign tasks to

personnel, and set up dependencies. Dependencies identify what needs to be done before

the next step can be completed—or what gets delayed when somebody drops the ball.

There are typically three major permits required when opening a new facility: building,

electrical, and fire. “Delays in the permitting process often affect the overall schedule,” says

Elenbark, so constant communication is a must. Weekly project meetings with the

implementation team will not only track progress towards project completion, but keeps

everyone informed of latest developments.

The goal is to begin operating out of the new facility as soon as possible. By the end of this

step, storage and material handling equipment should be installed; personnel should be hired

and trained; systems and equipment should be tested and debugged; and a certificate of

occupancy should be on hand. Only then can inventory be re-routed and received at this

location.

21 Tips for a successful greenfield project

1. Show your CEO that you’ve explored all options.

2. Don’t hesitate to hire consultants as a project partner.

3. Challenge forecasts. Show management their effect on inventory and movement to

see if they truly expect the business to grow that much within the projected design

period.

4. Beware of oversimplifying data and using averages. A plan is only as good as the

data and assumptions that are built into it.

5. Contact local business authorities, such as the Chamber of Commerce to assist in

site selection.

6. Consider staying close to the area of the old facility to maintain the same labor pool.

7. Watch inventory closely especially when increasing the number of DCs in your

network. Total safety stock will be higher in two-DC networks than a one-DC

network.

8. Avoid installing new warehouse management systems (WMS) at the same time as

a building move.

3

9. Consider bringing in 3PLs, but be sure to accurately compare the costs of how you

do business versus how they do business.

10. Consider subletting expansion space for the number of years that you don’t need it.

11. When installing complex mechanized systems and automation, consider first

simulating the operation. It lets you to test the concept on the computer—not on the

warehouse floor.

12. To save costs, consider purchasing used equipment. Make sure you test any used

equipment before purchasing.

13. Bring in local management or operations personnel as soon as possible. Hire ones

familiar with local authorities and contractors.

14. Set up the equipment necessary to obtain real-time control of the inventory as a first

priority.

15. Don’t lose control of the inventory. Make sure your systems are working to track

that inventory as soon as you receive it.

16. Rid yourself of obsolete or unwanted inventory before moving to a new DC. Don’t

make the mistake of moving these items.

17. Avoid rushing a project to completion because existing operations are scheduled to

shut down.

18. Get partial inspections and partial certificates of occupancy (COs).

19. Have all contractors and facility planners work from the same base plan or drawing.

Local building authorities sometimes impose changes to the design. The

implementation coordinator should take note of all changes, update the plans and

promptly circulate them to the appropriate parties.

20. Don’t forget the little things. New racks need signage. Inbound pallets need bar

coded license plates. New locations need to be entered into the system.

21. Use the latest technology and communication tools to plan and manage the project.

<< Return to Main Page | Print

© 2007, Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All Rights Reserved.

4