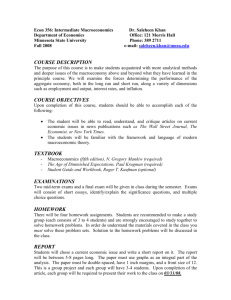

Economics for Business Syllabus

advertisement

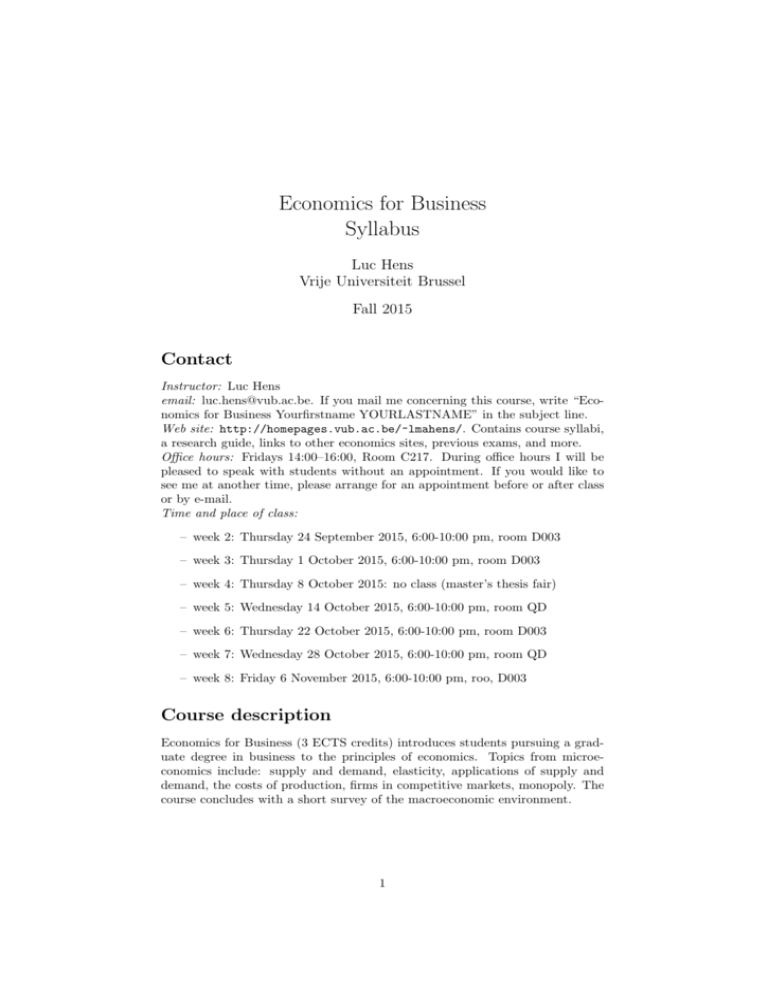

Economics for Business Syllabus Luc Hens Vrije Universiteit Brussel Fall 2015 Contact Instructor: Luc Hens email: luc.hens@vub.ac.be. If you mail me concerning this course, write “Economics for Business Yourfirstname YOURLASTNAME” in the subject line. Web site: http://homepages.vub.ac.be/~lmahens/. Contains course syllabi, a research guide, links to other economics sites, previous exams, and more. Office hours: Fridays 14:00–16:00, Room C217. During office hours I will be pleased to speak with students without an appointment. If you would like to see me at another time, please arrange for an appointment before or after class or by e-mail. Time and place of class: – week 2: Thursday 24 September 2015, 6:00-10:00 pm, room D003 – week 3: Thursday 1 October 2015, 6:00-10:00 pm, room D003 – week 4: Thursday 8 October 2015: no class (master’s thesis fair) – week 5: Wednesday 14 October 2015, 6:00-10:00 pm, room QD – week 6: Thursday 22 October 2015, 6:00-10:00 pm, room D003 – week 7: Wednesday 28 October 2015, 6:00-10:00 pm, room QD – week 8: Friday 6 November 2015, 6:00-10:00 pm, roo, D003 Course description Economics for Business (3 ECTS credits) introduces students pursuing a graduate degree in business to the principles of economics. Topics from microeconomics include: supply and demand, elasticity, applications of supply and demand, the costs of production, firms in competitive markets, monopoly. The course concludes with a short survey of the macroeconomic environment. 1 Course objectives This course aims to give students in business an understanding of how markets work, what makes markets more or less competitive, and how the external environment (the macroeconomy) influences a firm’s decisions. Course prerequisites This course requires that students understand graphs of two variables in the x–y coordinate system (Mankiw and Taylor, 2014, Chapter 2, Appendix, pp. 30–40). Review this material on your own. Also read the handout on percentages posted on the course home page. Skill development In Economics for Business, I try to develop the first four skills outlined in Hansen (2001, pp. 232–233): 1. Access existing knowledge: Retrieve information on particular topics and issues in economics. Locate published research in economics and related fields. Track down economic data and data sources. Find information about the generation, construction, and meaning of economic data. 2. Display command of existing knowledge: Explain key economic concepts and describe how these concepts can be used. Write a precis of a published journal article. Summarize in a two-minute monologue or in a 500-word written statement what is known about the current condition of the economy and its outlook. Summarize the principal ideas of an eminent economist. Elaborate a recent controversy in the economics literature. State the dimensions of a current economic policy issue. 3. Interpret existing knowledge: Explain and evaluate what economic concepts and principles are used in economic analyses published in daily newspapers and weekly news magazines. Describe how these concepts aid in understanding these analyses. Do the same for nontechnical analyses written by economists for general purpose publications (. . . ). 4. Interpret and manipulate economic data: Explain how to understand and interpret numerical data found in published tables (. . . ). Be able to identify patterns and trends in published data (. . . ). Construct tables from already available data to illustrate an economic issue. Describe the relationship among three different variables (e.g., unemployment, prices, and GDP). Explain how to perform and interpret a regression analysis that uses economic data. Text The required textbook is Mankiw and Taylor (2014) (ISBN 978–1–4080– 9379–5), available in the VUB book store and on amazon (amazon.co.uk or 2 amazon.de, about 76 euro). If you use an older edition, it is your responsibility to check the correspondence between the old and new editions. Some further material may be distributed during the course. Regularly check the news section from the course website and verify what happened during classes you missed. I expect you to follow the economic news in the press by reading a newspaper such as The Financial Times or The Economist (a weekly). Register for the Financial Times by going to the VUB library web site: http://www.vub.ac.be/BIBLIO/index_en.html > Databases > F You should use your VUB mail address as your user name. Once registered, you have full access to the Financial Times site (ft.com), and you can every morning download a pdf of the newspaper: go to http://ftepaper.ft.com; click on the European edition; then click on the floppy disk icon (top right) and choose “Download Newspaper PDF.” The weekly Economist newspaper is another good source of news (limited access on economist.com). If you prefer reading the paper versions, 4uCampus (www.4ucampus.be) offers considerable student discounts. Keep a file with newspaper clippings related to international trade subjects. I regularly post news updates on the course homepage. Keep a file with newspaper clippings related to economics subjects; try to organize them according to the chapter in Mankiw and Taylor (2014) they relate to. Preparation for class, attendance Carefully read the materials indicated in the course schedule before coming to class. Economics is a sequential subject: new topics build on concepts introduced before, so it is crucial to keep up with the material as we go along and to regularly review concepts. In the European Credit Transfer System (ECTS) the total workload for a 3-credit course is 75–90 hours. Bring the following things to class meetings: an A4 notebook with squared paper, a ruler with a centimeter scale, a mechanical pencil, an eraser, some colored pencils. Notebooks of the Atoma brand allow you to easily add, remove, and reorganize pages. You don’t have to bring the textbook to class. Attending classes adds value: concepts are reviewed, theory is applied to current events, and you can ask questions. I strongly encourage you to work additional problems. In the course schedule below, I list end-of-chapter problems from Mankiw and Taylor (2014) that apply what you learned in class. Problems of this kind may be part of the examination. I don’t distribute the solutions. The reason is that freshman students in another introductory economics class solve these problems in tutorial sessions. If I distribute the solutions, soon students will be sitting in the tutorials with the solutions in front of them and they won’t learn to think for themselves. You can find hundreds of solved numerical problems—similar to the ones in Mankiw and Taylor (2014)—in Salvatore and Diulio (2012). The older edition is fine, too. You can buy it used for a couple of euros at amazon.co.uk. 3 Teaching and assessment methods Economics for Business uses a mix of interactive classroom lectures and in-class problem sets. Students are assessed on basis of a written exam. The exam consists of two parts. The first, counting for about one fourth of the total grade, asks you to explain briefly a number of basic concepts. This is intended to find out whether you are able to speak the economist’s language accurately. A list of terms to be studied is included in Appendix A. The glossary is in the back of Mankiw and Taylor (2014, pp. 805–813). The second part (usually three questions) asks you to apply what you have learned by working case studies or by commenting at length on statements from the business and financial press, using the economist’s analytical toolbox. Bring the following things to the exam: your student picture ID, a mechanical pencil, an eraser, a blue pen, some colored pencils or pens (not red), and a ruler with a centimeter scale. Put everything in a transparant resealable (Ziploc) plastic bag. No phones or other electronic devices, no calculator, no pencil cases, no paper, no food, no paper tissues (use a handkerchief). A 50 cl water bottle is allowed if you remove the label. Don’t mail or call me to inquire about your grade—I don’t communicate grades by mail or by telephone. Course schedule Consult the course home page regularly (at least once a week) for announcements and possible schedule changes. The material listed should be read carefully before the class meeting. Study the key concepts listed at the end of each chapter. There is a list of concepts to be known for the final exam in Appendix A. Week 2 (Thursday 24 September 2015) Read carefully: “How To Read This Book” (Mankiw and Taylor, 2014, Chapter 1, p. 14) and “Appendix: Graphing and the Tools of Economics: A Brief Review” (Mankiw and Taylor, 2014, Chapter 2, pp. 30–40). The Market Forces of Supply and Demand (Mankiw and Taylor, 2014, chapter 3). Skip: “Finding Price and Quantity Using Algebra” (p. 49), “The Algebra of Supply” (p. 54), “The Algebra of Market Equilibrium” (pp. 59–62) and the related problem 10 p. 71. Work problems 7 and 9. Elasticity and its applications (Mankiw and Taylor, 2014, chapter 4). Skip: “Using the Point Elasticity of Demand Method” (pp. 75-76), “Other demand elasticities” (pp. 81-82) and “FYI: The Mathematics of Elasticity” (pp. 90–95). Work problems 4 and 5. Week 3 (Thursday 1 October 2015) Consumers, Producers, and the Efficiency of Markets (Mankiw and Taylor, 2014, Chapter 7). Work problems 4, 5, 6, 9 (problems of this kind may be part of the examination). Supply, Demand, and Government Policies (Mankiw and Taylor, 2014, Chapter 8). Skip: “An Ad Valorem Tax on Sellers”, “The Algebra of a Specific 4 Tax”, “Elasticity and Tax Incidence” (pp. 194-197). Work problems 3, 4, and 7. The Tax System and the Costs of Taxation (Mankiw and Taylor, 2014, Chapter 9). Only pp. 203–207; skip the rest of the chapter. Work problem 1. Externalities and Market Failure (Mankiw and Taylor, 2014, Chapter 11). Skip: “Private Solutions to Externalities” (pp. 244–247), “Public/Private Policies Towards Externalities” (pp. 251–254) and “Government Failure” (pp. 254– 259). Work problems 1, 2 and 6. Week 4 (Thursday 8 October 2015) No class: master’s thesis fair. Week 5 (Wednesday 14 October 2015) Firms in Competitive Markets (Mankiw and Taylor, 2014, Chapter 6). Skip: “Costs in the Short Run and in the Long Run” (pp. 145–146), “Returns to Scale” (pp. 147–153), “The Firm’s Short-Run Decision to Shut Down” through “The Firm’s Long-Run Decision to Exit or Enter a Market” (pp. 157–159), and “The Long Run: Market Supply and Entry and Exit” through “Why the Long-Run Supply Curve Might Slope Upwards” (pp. 161–164). Work problems 1, 3 and 8. Week 6 (Thursday 22 October 2015) Monopoly (Mankiw and Taylor, 2014, Chapter 14). Skip “Price Discrimination” (pp. 303–306). Work problems 1 and 5. Week 7 (Wednesday 28 October 2015) The Macroeconomic Environment. The circular-flow diagram (Chapter 2, pp. 22–23). (Other chapters to be announced.) Week 8 (Friday 6 November 2015) The Macroeconomic Environment (Chapters to be announced.) Exam period (11–30 January 2016) Written exam. Time and place to be announced. The exam covers all the material listed in the schedule above (even if we didn’t discuss it in the class meetings). Bring the following things to the exam: your student ID, a mechanical pencil, an eraser, a blue pen, some colored pencils or pens (not red), and a ruler with a centimeter scale. Put everything in a transparant resealable (Ziploc) plastic bag. No phones or other electronic devices, no calculator, no pencil cases, no paper, no food, no paper tissues (use a handkerchief). A 50 cl water bottle is allowed if you remove the label. 5 A Concepts These are the key concepts for which you have to study the definitions for question 1 of the final exam. The glossary is in Mankiw and Taylor (2014, pp. 805–813). Chapter 3: competitive market, substitutes, complements Chapter 4: price elasticity of demand, price elasticity of supply, total expenditures, total revenue. Chapter 6: marginal product, diminishing marginal product, fixed costs, variable costs, marginal cost, marginal revenue. Chapter 7: consumer surplus, producer surplus, total surplus, efficiency Chapter 8: — Chapter 9: deadweight loss Chapter 11: externality, internalizing an externality, Pigovian tax. Chapter 14: monopoly, natural monopoly Chapter 20: gross domestic product (GDP), real GDP, nominal GDP, GDP deflator Chapter 21: consumer prices index (CPI), inflation rate, nominal interest rate, real interest rate. Chapter 26: central bank, open-market operations, reserves, reserve ratio, refinancing rate, reserve requirements, money multiplier Chapter 29: quantity theory of money, shoe leather costs, menu costs. Chapter 30: recession Chapter 32: aggregate demand curve, aggregate supply curve. Chapter 33: theory of liquidity preference, crowding-out effect. References Hansen, W. L. (2001). Expected proficiencies for undergraduate economics majors. Journal of Economic Education, 32(3):231–242. Mankiw, N. G. and Taylor, M. P. (2014). Economics. Cengage Learning, Andover, 3rd edition. Salvatore, D. and Diulio, E. (2012). Schaum’s Outline of Principles of Economics. Schaum’s Outline Series. McGraw-Hill, New York, 2nd edition. 6