Generalization Schwartz Social Values Scale 1 RUNNING HEAD

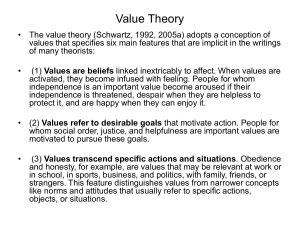

advertisement