to read it - André Naffis

advertisement

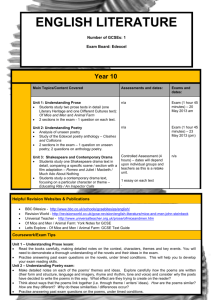

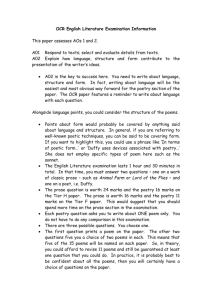

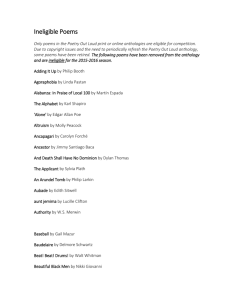

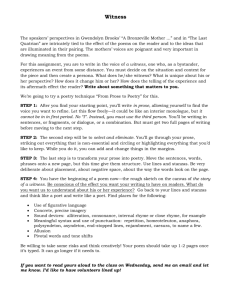

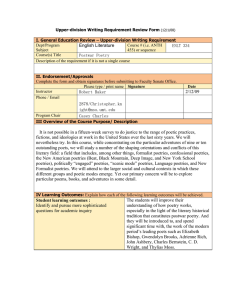

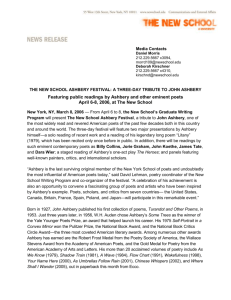

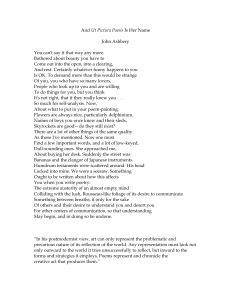

26 POETRY I By Jonas Berry t’s easy to fall in love with early twentiethcentury Paris, which as Denis de Rougemont once pointed out, “was the geometric locus of the modern adventure”. You can attach a seismically important name to every letter of the alphabet twice over – Apollinaire, Breton, Char, Diaghilev, Éluard, Follain, Gide – then spend a lifetime reading issues from the first three decades of the Nouvelle Revue Française and never shake the feeling you were at the heart of the ferment. Although Paris had long ceased to be an open-air laboratory by the time John Ashbery lived there – from 1958 to 65, having previously been a Fulbright scholar in Montpellier and Rennes from 1955 to 57 – Americans were still so uninformed about how the artistic landscape had been dramatically and irrevocably broadened, that Ashbery had his work cut out for him. He took to it seriously, ferrying those innovations back across the Atlantic to eager converts. These two volumes of Ashbery’s Collected French Translations are the summation of seven decades of Francophilia and resoundingly confirm Ashbery’s reputation as a master translator. For all the emphasis on modernism – only three of Ashbery’s forty authors were born before the mid- nineteenth century – the Prose volume opens with a charming and hugely entertaining fable by Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy (1650–1705). “The White Cat” affords a window onto Ashbery’s penchant for verbal playfulness. The typical boy-meets-girlbreaks-spell-they-live-happily-ever-after plot is merely a vessel for thirty pages of deliciously entertaining digressions. An old king who refuses to abdicate in favour of any of his three sons instead decides to send them on three pointless errands, promising them that whoever triumphs will inherit the realm, although he has absolutely no intention of keeping his word. The princes’ three quests are to find: “the most beautiful little dog”, “a piece of cloth so fine that it would pass through the eye of a Venetian lacemaker’s needle” and “the most beautiful maiden”. Not long after setting off on his first adventure, the youngest prince chances on a castle with a golden gate whose walls are made of translucent porcelain. The castle is ruled by “the most beautiful White Cat that ever was or T alking Vrouz, the second collection of Valérie Rouzeau’s poems to be translated by Susan Wicks (who was awarded the Scott Moncrieff Prize for the earlier work) is another tour de force in which the translations succeed in being faithful to the letter (mostly) and generous spirit of Rouzeau’s French poems, while being perfectly capable of standing – no, dancing – on their own as English poems. Clearly, these two poet-translators (Rouzeau has translated Sylvia Plath, Emily Dickinson and William Carlos Williams) were meant to team up – or they were extraordinarily lucky. Rouzeau (b. 1967 ) has published more than a dozen volumes in French, including Vrouz (2012), a collection of short self-portraits (as indicated by the title: VRouzeau) that won France’s venerable Apollinaire Prize. Talking Vrouz contains a selection of poems from Rouzeau’s earlier collection, Quand Je me deux (2009), and fifty-eight of the 161 sonnets, or fourteen-liners, that compose Vrouz. Readers of Wicks’s English versions will find all Rouzeau’s exhuberant linguistic playfulness, a ANDRÉ NAFFIS-SAHELY John Ashbery COLLECTED FRENCH TRANSLATIONS Prose 424pp. 978 1 84777 235 0 COLLECTED FRENCH TRANSLATIONS Poetry 460pp. 978 1 84777 234 3 Edited by Rosanne Wasserman and Eugene Richie. Carcanet. Paperback, £19.95 each (US, Farrar, Straus and Giroux. $35 each) ever will be”. Charmed by the young prince’s kindness and manners – who says nice guys finish last? – the White Cat handily provides him with everything he needs to please his father. While everyone’s favourites will be different, there are sufficient gems studded throughout this two-volume set to keep any reader coming back. The range is refreshingly wide: from fables and prose poems to lyrics, critical essays (Michel Leiris on Raymond Roussel is not to be missed) and excerpts from novels – and even mock-dialogues, including Alfred Jarry’s “Fear Visits Love”’: FEAR: Your clock has three hands. Why? LOVE: It’s the custom here. FEAR: Oh dear, why those three hands? I’m so upset . . . LOVE: Nothing could be more simple, more natural. Calm yourself. The first marks the hour, the second draws along the minutes, and the third, always motionless, eternalizes my indifference. Or, say, a ten-month correspondence between Antonin Artaud (1896–1948) and Jacques Rivière (1886–1925), which begins with Rivière writing, “Sir, I regret not being able to publish your poem . . .” and ends with him affirming “How shall we distinguish our intellectual or moral mechanisms, if we are not temporarily deprived of them?” The list could go on. The Poetry volume features twenty- five poets, while the Prose has seventeen writers, with only two authors overlapping. Of particular interest are Ashbery’s takes on Yves Bonnefoy, Stéphane Mallarmé, Pierre Reverdy, Pierre Martory (arguably his closest confrère) and, of course, Roussel. Perhaps one of the highlights – or one of my favourites, at any rate – is the generous selection of Max Jacob’s prose poems, from Le Cornet à dés/The Dice-Cup. This alone would justify at least half the set. Here is “The Beggar Woman of Naples”: When I lived in Naples, there was always a beggar woman at the gate of my palace, to whom I would toss some coins before climbing into my carriage. One day, surprised at never being thanked, I looked at the beggar woman. Now, as I looked at her, I saw what I had taken for a beggar woman was a wooden case painted green which contained some red earth and a few half-rotten bananas. As Ashbery is so inventive in his own poetry, one might naively expect him to exercise an unnecessarily free hand, but he is actually a remarkably faithful translator. Although space constraints make this impossible with the Prose, the Poetry features the originals en face. An examination of “La Mendiante de Naples” will show how Ashbery’s version is pitch-perfect and exacting, employing precisely as many words as the original (or rather three more, but only because “beggar woman” must count as two words). Usually, Ashbery favours AngloSaxon words over Latinate ones, felt choices over rigorously correct. Opting for the latter over the former tends to produce a turgid foreignese rather than an accurate “mirror image”, which is why Ashbery’s kind of sensibility seems to me the mark of a true translator. Collected French Translations was assembled by Rosanne Wasserman and Eugene Richie, who have done a sterling job. Their commendable introduction treats the reader to not a few interesting stories, for example how Ashbery – or rather, his alter ego, “Jonas Berry”, a phonetic rendering of the French mis- At top speed BEVERLEY BIE BRAHIC Valérie Rouzeau TALKING VROUZ Translated by Susan Wicks 142 pp. Arc. £13.99 (paperback, £10.99). 978 1908376 17 6 willingness to follow where sound leads (“paradise / Or spaghettini spiced / With pesto portuguaise”); sudden changes of direction and omissions that wink at the ponderous pace of step-by-step logic; and an eclectic focus on the everyday. Events and thoughts that might, at first glance, seem banal or childlike reveal, on closer examination, depths expressed with poignancy, humour and freshness. There is narrative, often subliminal or fragmentary, and self-portrayal. The reader is beckoned into an ongoing conversation about love affairs, owls and snowflakes, the domestic: “Don’t rent a lorry I can move your stuff / I’ve got a little van your things will fit in fine / Smile you’re just moving house you’re off to better days / New love who knows / And everything to live for both arms all your teeth . . .”. Lists figure in many poems, in a variety of registers. Punctuation is employed sparingly, but Rouzeau and Wicks are expert at constructing lines so that the absence of punctuation feels natural, all the more so as the poems seem as much spoken as written – snippets of conversation with loose ends and swerves: “This may not be exactly what we mean / By poem but I was wondering why I’d whisked this cloth away / From grandma’s wardrobe yesterday when she died / The pattern isn’t daisies but two ducks / Two big fat ducks twelve oranges /. . . . Among the pelicans the cranes the Père Ubus / And everything mislaid with my loose screws”. Here,Wicks has slyly contrived to TLS OCTOBER 3 2014 pronunciation of his name – translating two pulp detective novels to earn money during his Parisian sojourn, spiced them up with “some soft-core sexy passages”. It has become rather fashionable to display at least a passing interest in translation. There may be a commercial aspect to this: poems, like all truly globalized goods, must either transcend local markets or perish in a puddle. To remain stubbornly monocultural now seems shamefully provincial, and this is no bad thing as long as it represents an actual, long-term engagement – but the poet who spends the entirety of his or her creative life in communion with a language other than the one he or she writes in is still as rare as a unicorn. Ashbery has often been described as a French surrealist camouflaged as an American poet, but ultimately one may say of him that he is no more French than American (and vice versa), and, adapting what Jacques Dupin said of Giacometti (in “Texts for an Approach”, which is included in the Prose), that we cannot separate his poems from his translations – or, in Giacometti’s case, his paintings from his sculpture – because “the two means of expression are . . . but the tools of the same research and the same experiment. They complete each other, support each other mutually; the exchanges between them are constant and each advance in one has immediate repercussions on the other”. On April 3 this year, exactly sixty years after his first appearance there, Ashbery regaled the crowd at the New York 92nd St Y with excerpts from this Collected as well as poems from his forthcoming new collection. In one of the latter, Ashbery referred to himself as “the custodian of sang froid”. He’s not wrong: it takes a steady, audacious hand to move past the five senses into the uncertain area in which we could be either the makers of our own experiences or the receptacles of otherworldly revelations. In this, Ashbery manages to be absolutely modern in the way Rimbaud demanded. While fans of his Illuminations, or The Landscapist, his indispensable selection from Martory, may baulk at the pricetag, Collected French Translations, like anything by Ashbery, is worth owning and rereading; we should be grateful for this monument to the riches that his level of dedication can yield. keep the final rhyming couplet of the original stanza (though there are no “screws” in it but “ubus . . . plus”), and she has done so while hewing to the original sense. Elsewhere (“Vain Poem”) Wicks, challenged to translate the wordplay of “élégants gants”, rises to the occasion with “glovely gloves”. The polysemy of “Les rues sales leurs noms propres” proved trickier, however, and I sympathized with Wicks’s (projected) annoyance at having to make do with “The sordid streets their very proper names”. Here is the octet of a “Vrouz”: “I’m good for this or nothing / Never learnt to swim can’t dance can’t drive / A single car not even one that’s small / Can’t sew can’t count can’t fight can’t fuck / Can’t master how to eat or cook / (I’ll ask someone to scramble me an egg) / And as for drinking that’s a real dead loss / But dying is impossible right now. . .”. Emotionally and perceptually charged, Valérie Rouzeau’s poems are also down-to-earth, shape-shifting and witty. They dart off on their errands at top speed, and we run to keep up. They are a delight in both French and English. Chapeau!

![Special Author: Ashbery [DOCX 14.37KB]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006871569_1-e4adbb0354f7f806543fcc0a123d8597-300x300.png)