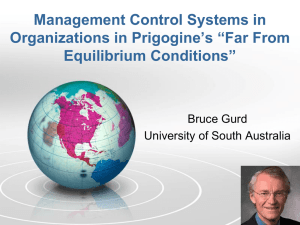

Examining the nature of management control system interrelationships

advertisement