The Founding of the MIT AI Lab

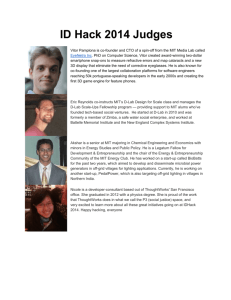

advertisement