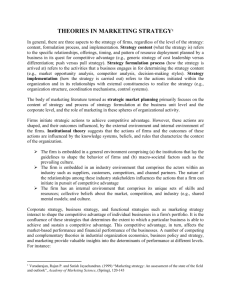

Market Structure, Conduct and Competitive Strategy

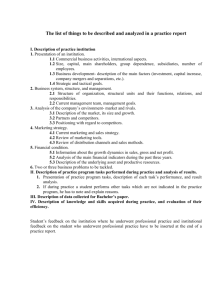

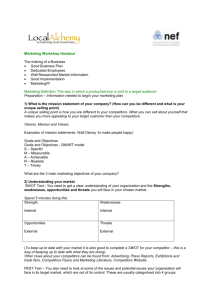

advertisement