Gastroenteritis at a University in Texas

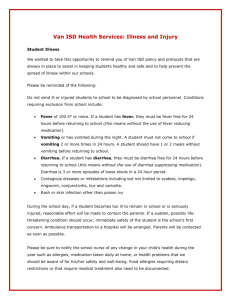

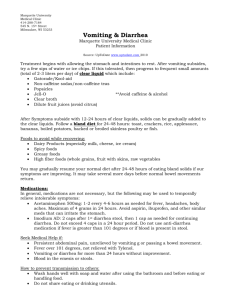

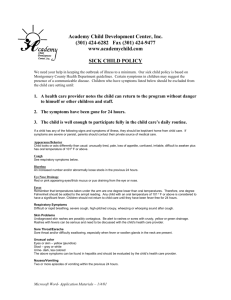

advertisement