E. Medical Complications (Questions, Answers, and Discussion)

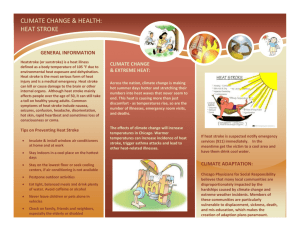

advertisement