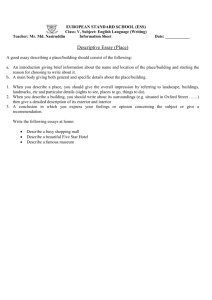

College Composition/ College Composition Modular

advertisement