FACULDADE DE MEDICINA PROGRAMA DE PÓS

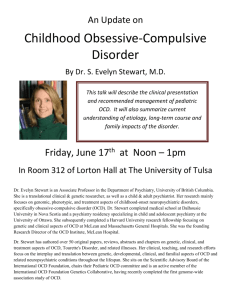

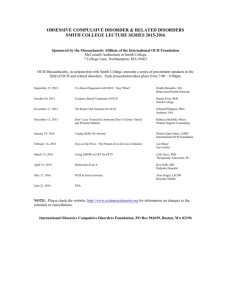

advertisement