International Journal of Case Method Research & Application (2007) XIX, 2

© 2007 WACRA®. All rights reserved ISSN 1554-7752

GRADING STUDENT CASE ANALYSES:

AN EVALUATION SYSTEM

Tom Morris

University of San Diego

SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA, U.S.A.

Abstract

Faculty members using the case analysis method of teaching value its diversity and

richness as a learning instrument and often wish to develop a systematic approach to

evaluating student performance in written case analysis. At the same time, they also

often wish to reduce the time expended in evaluating and/or grading these same cases.

This Case Evaluation System provides a quick and comprehensive way to provide quality

student feedback on written cases. The system revolves around the integrated use of the

Executive Summary format and a corresponding Case Evaluation Matrix. It provides an

evaluation continuum of the important case analysis elements as determined by the

faculty member. This system eliminates the need for repetitive comments on each case,

and with a quick circle or check notation gives valuable feedback to the student. It also

reinforces the need for students to consider each of the important analysis elements.

KEY WORDS: Grading, case writing, case study method, student feedback, evaluation,

executive summary format

INTRODUCTION

The case method of study has always been an enjoyable and rewarding learning experience for both

a student and faculty member. Perhaps this is due to the unconstrained way of thinking about approaches

to problem resolution. However, it was only as a faculty member that the appreciation in the difficulty of

evaluating student papers and assigning grades to their creative efforts became apparent. This resulted

in the development of an evaluation system that involves the use of the Executive Summary format

(Exhibit 1) for writing cases and a Case Evaluation Matrix (Exhibit 2) for grading them. The two work

together in an integrated fashion and can be modified to suit individual criteria if desired.

The Executive Summary format is used for the writing of cases because it is commonly used in

business as a preface to long, complex proposals. Most business executives do not have the time to read

complex proposals, especially when the proposals span many disciplines, such as R&D, finance,

marketing, manufacturing, transportation, import/export, etc. But business executives can and will read a

concise two or three page summary which provides the essential elements of the proposal. Accordingly, it

is important for students to be able to write a concise summary of a complex business issue as a part of

their preparation for the business world.

One obvious question always arises when considering the value in writing the cases. That is, why

bother writing them at all? These cases are invariably discussed in class, opinions expressed and

recommendations made. Isn’t this just as good as writing them? In the author’s opinion...no! As a

student, preparation for a case discussion was always more in-depth when a written recommendation

was required. Thus, it is not surprising that class discussions are also much better when all the

participants have also written case recommendations. What makes the discussions better is not only that

154

International Journal of Case Method Research & Application (2007) XIX, 2

the students have thoroughly read and thought about the case, but that they have made a commitment in

writing (a recommendation) that somehow requires some defense, which leads to stronger support

positions for various alternative recommendations. This results in a livelier, more comprehensive case

discussion.

The problem for the faculty member leading this enhanced case discussion is, of course, how to deal

with all the written cases. (A brilliant graduate assistant comes in very handy here, but we are not always

blessed with one.) It was ultimately concluded that in order to develop good, concise, writing skills, some

qualitative feedback on each paper was required.

At one time, about half an hour was spent on each case, including written comments on each paper.

Several things happened when employing this method. First, hundreds of hours were spent commenting

on the papers, and the comments were very repetitive from one paper to the next. Second, after making

all the comments, there was no easy way of ordering them into a specific grading mechanism.

Fortunately, the structure of the Executive Summary format combined with the Case Evaluation Matrix,

make for an efficient evaluation of student papers and provide useful, high quality feedback. A

comprehensive case evaluation can now be completed in about ten minutes.

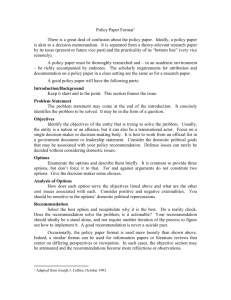

THE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY FORMAT

The Executive Summary Format (Exhibit 1) is particularly good for evaluating student cases because

it is structured and concise. When evaluating a large number of student papers, the identical structure of

each paper provides for a quick focus on the critical elements of the paper, including problem statement,

discussion and recommendation. Students receive a copy of this format before writing their first case. It is

also very helpful to provide a specific example of a case that has been written in this format. It is usually a

case that has been assigned for class discussion, and it provides the students with a good example to

follow. Sometimes, a good student paper may be used as an example if the case has been written before.

But more often, the author creates the example himself. The Executive Summary example of the case

may be handed out near the end of the class discussion and used as the concluding summary of the

case. Students find the specific example written in the required format extremely helpful in ordering their

thoughts and making the transition from thinking to writing. In virtually every class, the quality of written

cases improved dramatically after the sample was introduced, and it did not appear to stifle any creativity.

So naturally, this step is heartily recommended.

Some students find the limitation of three pages to be difficult, because they feel it does not allow for

a complete development and expression of ideas, particularly if the case is long and/or complex. It should

be pointed out that it is not intended to be an exhaustive analysis of all possible alternatives, but rather a

concise, focused summary with the alternatives only mentioned to ensure they received consideration. In

general, any issue, no matter how complex, can be summarized into three pages if the case is reduced to

its most essential elements. Exhibits, tables, financial analysis, etc. may be included as attachments and

are not typically included in the three-page limit.

INTRODUCTION

The introduction is used to provide some general background from the case and introduce the

particular issue that is the primary focus of the case. Typically, students use the introduction as a sort of

“warm up” for structuring their approach to the case. It’s usually a single, short paragraph, and students

are encouraged to use their own summary skills rather than any words from the case author.

PROBLEM STATEMENT

The problem statement is always the most difficult part of the format for students, partly because the

problem (or issue) is usually not directly stated in the case. However, this is the most important part of the

case analysis, because it requires a thoughtful analysis and synthesis of information. Most cases are

loaded with superfluous information that has little bearing on the real issue presented in the case, and a

clear statement of the problem allows for a focused recommendation. If the problem is fuzzy and not

clearly stated, then the resolution is usually equally fuzzy and does not bring closure to the issue. The

best problem statements can be made in a single sentence. For example, “Sales are declining, and

International Journal of Case Method Research & Application (2006) XIX, 2

155

profitability has slipped from 10 percent to 5 percent over the past five years.” Or, “The Acme Company

does not have sufficient capacity to meet the forecasted demand of 10 million units per year.” If possible

it is always better to quantify the problem, because it helps to bring specific closure to the

recommendation.

Students sometimes frame the problem in terms of a general solution, such as, “The company must

determine how to increase sales and increase profits.” Or, sometimes they even put the specific

resolution into the problem statement, such as, “The Acme Company must borrow sufficient capital to

build a new manufacturing plant.” It must be pointed out that these are not problems, but possible

solutions to unstated problems. When students introduce solutions in the problem statement, it eliminates

the discussion of alternatives.

ENVIRONMENTAL ANALYSIS

This section of the format allows the student to frame the issue in the appropriate context of the

department, the company, the industry, the product line, the market, etc. It provides the student the

industry norms that can be stated to show relationships and relative strengths or weaknesses. If

resources are an issue, this is the place to discuss it, as well as issues such as the market, competition,

customers, technology, government regulations, legal requirements, social trends, personnel,

interpersonal relations, etc. This section often consumes two pages of a three-page paper, and it can be

quite comprehensive.

ALTERNATIVE STRATEGIES

Clearly, there is always more than one way to resolve the stated problem. This section forces

students to consider alternative solutions. It does not require a comprehensive discussion of each

alternative, just a demonstration that the student is aware of the alternatives to counter the typical

challenges of, “Have you thought about..., etc.?” This is an opportunity for the student to demonstrate

creative insight as well as clear, logical reasoning.

RECOMMENDATIONS

This section becomes the essence of the paper. Assuming that the student has correctly identified the

problem, has conducted a thorough environmental analysis, and has come up with a few alternative

solutions, he/she is free to present the logic of the recommendation. The key here is whether or not the

recommendation actually resolves the stated problem. This seems like an obvious requirement, but many

students will make a very persuasive argument for their recommendation, only to ultimately find out that it

does not resolve the stated problem. The recommendations should be very specific. That is, a

recommendation to “increase capacity” must also be accompanied by an explanation of the approximate

cost and exactly how the resources to fund the increased capacity will be obtained. Not long ago, we

studied the airline industry and one of the specific airline companies in the industry. This particular airline

company was in Chapter 11 bankruptcy. However, this did not dissuade several students from

recommending “the acquisition of 50 new planes and expansion into international routes,” but without the

accompanying explanation on how much these planes might cost, or how the airline could afford to

acquire them. Clearly, any recommended strategy must be stated specifically, and it must also be

possible.

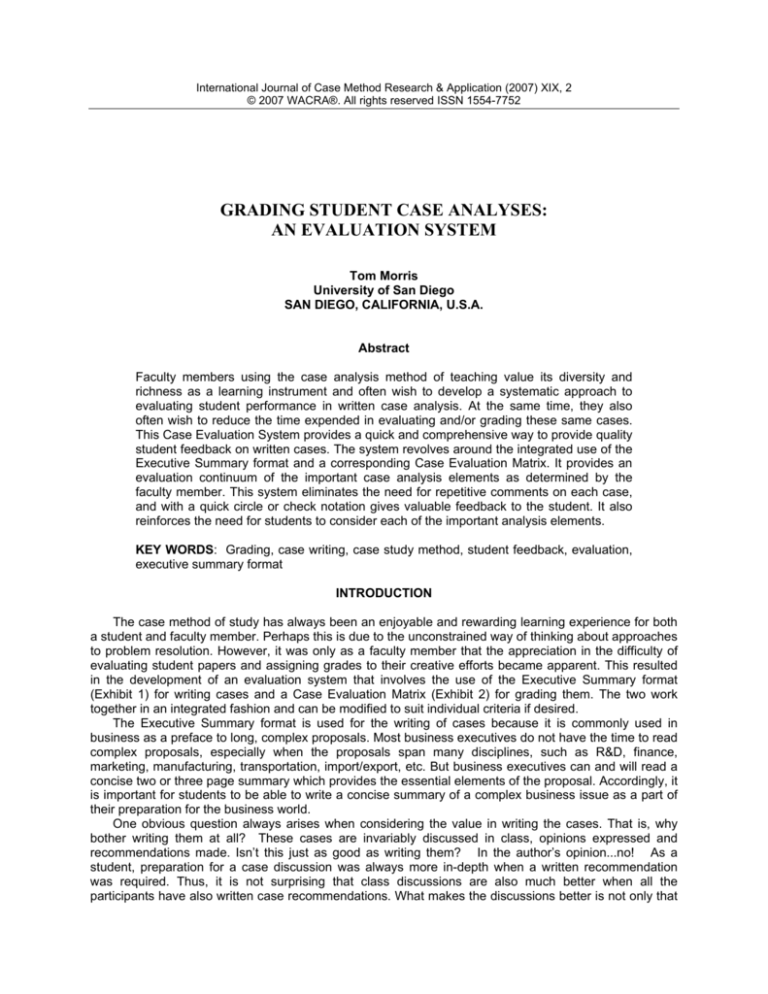

THE EVALUATION MATRIX

The matrix (Exhibit 2) presented in this paper has evolved over several years, and it can be used in

both graduate and undergraduate classes. It provides an evaluation continuum of the important case

analysis elements as determined by the faculty member. It eliminates the need for repetitive comments

on each case, and with a quick circle or check notation gives valuable feedback to the student. It also

reinforces the need for students to consider each of the important analysis elements.

At one time, the continuum was used to assign specific grades at each level, one for each analysis

component. The left-hand column of the matrix is reserved for this purpose and provides for a nice,

156

International Journal of Case Method Research & Application (2007) XIX, 2

straightforward grading mechanism. More recently, the specific grade assignment of each component has

been dropped in favor of the “holistic” nature of the effort when assigning a grade or score. This results in

a sort of structured subjectivity which is preferable to the inevitable weighting of each component to

determine a grade or score. In this format, the components are not equally weighted. For example, a

creative and insightful recommendation is not always accompanied by a comprehensive analysis of

issues. Both elements are required, but an excellent, intuitive recommendation is better than a thorough

analysis of issues that leads nowhere.

This matrix has been designed for use with this executive summary. However, it can be modified to

suit individual needs. If the instructor chose a written case format with six or eight important elements,

then the horizontal matrix could be expanded to accommodate the additional elements. For example, the

instructor might want to include alternative strategies as a key element, or one could choose fewer

elements but with different criteria. The progression or grading continuum on the vertical axis of the matrix

can likewise be expanded or contracted depending on one’s ability and desire to clearly differentiate the

steps in the continuum. For example, if the instructor wants to differentiate between five different grades,

A through F, then he/she needs five steps. If the instructor wants to differentiate only between three

grades, A, B and C, then he/she needs only three steps.

In this 5 X 5 matrix, three of the horizontal elements are the critical components of the case analysis:

problem identification, analysis of issues and specific recommendation. The other two elements are more

subjective, but they are necessary to acknowledge creativity and writing clarity. Generally, most papers

create a predictable set of alternatives and provide support for one or more predictable, well founded

reasons. However, sometimes a student will formulate a very unusual and creative recommendation that

can be acknowledged under the “creative insight” element.

The vertical grading continuum provides information that increases the student’s ability to structure

specific, well written papers. It tells them both what to do in order to meet expectations for a good paper

and what not to do to avoid being downgraded for a writing effort. Thus, by simply circling the appropriate

box in the matrix, the instructor is telling the student both what they have done and what they need to do

to improve their case presentation, and all without writing repetitive, time-consuming notes on each

paper.

The matrix does not necessarily remove the need for individual comments. Comments can be made

in the margins of each case and written at the bottom of the matrix page. However, because of the matrix,

it is no longer necessary to write a repetitive rationale for the grade on each paper.

CONCLUSION

This evaluation system is continually evolving. It clarifies expectations for a good paper, shows

students how to improve their writing, and reduces the time spent grading. It makes it easier to justify a

written case by creating a balance between the enhanced learning process and the time spent evaluating

it. Hopefully, someone else will find this system conceptually useful and be energized with an idea to

create an even better system. If the reader does so, please send the author a copy.

EXHIBIT 1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY FORMAT

The executive summary is designed for the executive who wants an understanding of an issue, an

analysis and recommendation, but without all the analysis detail. Executive summaries are often the first

few pages of a comprehensive analysis, they are normally two pages, and they should never exceed

three pages (plus any attachments).

INTRODUCTION

The introduction is a brief, one-paragraph description of the major issues presented in the case. This

should include any economic, political, market or competitive issues. It may include organizational issues,

technical issues, financial issues, ethical issues, policy considerations, etc.

International Journal of Case Method Research & Application (2006) XIX, 2

157

PROBLEM STATEMENT

The problem statement is a specific statement of the problem or issue, usually not to exceed two

sentences. Remember that this is not a question nor a direction to proceed; it is only a statement of the

problem.

ENVIRONMENTAL ANALYSIS

The environmental analysis is an analysis of critical internal and external issues that bear most

significantly on the case. These issues may be related to a department, company, market, country,

product, competitor, company policy, industry, etc.

ALTERNATIVE STRATEGIES

Alternative strategies are possible alternative solutions to solve the problem. These should be specific

and distinct from one another. Briefly note advantages and disadvantages of each possible alternative.

One of the most useful purposes of this section is to demonstrate that you have not overlooked any

obvious alternatives.

RECOMMENDATION(S)

The recommendation is an explanation of your specific recommended strategy(ies), why you selected

that particular one and how it solves the problem. It might include an appropriate financial analysis. Be

sure your recommended strategy can be supported with available resources.

EXHIBIT 2

CASE EVALUATION MATRIX

Grade

Problem

Identification

Analysis

of issues

Recommendation

Creative

Insight

Writing

Style

Clear,

specific,

concise and

accurate

Comprehensive,

no omission

of issues

Clearly resolves

the problem

Original

with

unusual

insight

Stimulating

and has no

errors

Generally

accurate but

not concise

and specific

Includes most

important

issues

Solves the problem

in a general sense

only

Generally

good, solid

reasoning

Clear and

interesting

with no

errors

Part of the

problem not

identified

Overlooks

some

issues

Solves only a

part of the

problem

OK – but

suggests

only the

obvious

Clear, but

with a few

errors

158

International Journal of Case Method Research & Application (2007) XIX, 2

Vague

problem

definition

Omits some

of the

important

issues

Vague

problem

definition

Missing

some

insight

Difficult

to follow

Inaccurate

assessment

of the

problem

Omits all

of the

important

issues

Doesn’t

solve the

problem

at all

Misses

the

point

completely

Incomplete

thoughts,

confusing,

excessive

errors

COMMENTS