Emily Dickinson's Poetic Covenant

advertisement

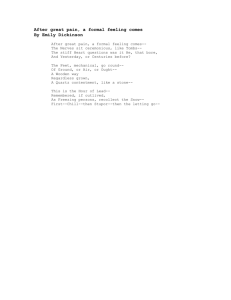

Emily Dickinson's Poetic Covenant The study of Emily Dickinson’s poetic oeuvre is a lesson in literary and cultural history. Trying to appreciate her poems means to try and understand the cultural roots from which she emerged and to appreciate the cultural milieu in which she lived. The late Karl Keller’s wide-ranging study The Only Kangaroo Among the Beauty: Emily Dickinson and America that locates Dickinson’s work in its overall American literary context is as indispensable to the reader of her poems as is Barton Levi St. Armand’s admirably detailed research into Dickinson’s background of New England popular culture. The same holds true for a number of feminist studies like those by Gilbert/Gubar, Homans, Mossberg, Pollak and Dobson that all help us understand the poet’s specific situation as a woman writer in mid-nineteenth century Victorian America. Among the many excellent books now available, no critic seriously interested in Dickinson’s lyric achievement can bypass the seminal works of Brita Lindberg-Seyersted, Robert Weisbuch and Sharon Cameron. Nor can the reader do without Richard B. Sewall’s magisterial biography of the poet and - more recently - the lively and astute account of Dickinson’s life and work by Cynthia Griffin Wolff. At the same time, the European reader is astonished to note that Dickinson’s work functions like a sounding board of much that is central to his or her own culture: medieval texts (in particular Dante), Shakespeare, English Metaphysical and pre-Romantic poetry as well as the Romantic and Victorian writers. He is amazed, moreover, to discover that - the problematic case of Poe and his French admirers apart - the symbolist mode first achieved its full-fledged realization in New England, not in France. In a very real sense, Dickinson is a deeply provincial writer, yet her modernist techniques as well as the universality of her themes establish this poet as a transatlantic, even cosmopolitan, author ranking with the classics of the Western tradition. Thinking in Alternatives Dickinson’s rich heritage makes the study of her poetry an adventure; however, it also raises the vexing problem of interpretative indeterminacy (Hagenbüchle, “Precision and Indeterminacy” 33-56). Not only does the reader find it hard to disentangle the cultural layers and to decide their relative weight, but the literary voices themselves rarely come through clear and unambiguous. In fact, they often seem to compete with each other, as if the author herself had been unwilling to take a final stand. Despite its careful annotation of textual variants, Thomas H. Johnson’s standard edition creates a false impression since his editorial decisions - Smith speaks of “mutilations” (16-22) - tend to erase what is a crucial feature of Dickinson’s poetry: its processual and dialectical quality (Hagenbüchle, “Aesthetik” 245-46, 253; “Sign and Process” 147-48). To some of her poems Dickinson has added alternative endings that flatly contradict each other. Although such cases are relatively rare, her verse invites (and sometimes even enforces) seemingly irreconcilable readings, not least because textual variants tend to branch off into conflicting versions. Differences in exegesis between critics like E. Miller Budick and Greg Johnson, who both offer attractive but mutually exclusive readings of the poem "Before I got my eye put out" (327), serve to illustrate this point. What we are confronted with here is a hermeneutic problem that far exceeds the more technical question of semotactic ambivalence. The very possibility for alternative interpretations underscores the poet’s deep-rooted antipathy to thinking in clear-cut oppositions. 2 For Dickinson, faith is not faith because it has overcome doubt, rather “Faith is Doubt.” (L912) Similarly, “Earth” cannot be opposed to “Heaven;” “Earth” rightly understood is “Heaven” (PF114) and “Reality itself [. . .] a Dream.” (PF2) Since we have all been educated in systematic either-or reasoning, it is hardly surprising that Dickinson’s poetic language tends to throw us into utter confusion. Dickinson’s title-less verse displays no “what,” no overt subject matter, so that our search for a poem’s underlying theme, its experiential center, frequently ends in puzzlement. An especially troublesome problem is the lack of a stabilizing frame. Tone and perspective tend to switch abruptly, often within a single poem. In many cases, the rhetorical mode remains irritatingly ambivalent so that the reader is left wondering whether a poem’s ostensible statement can really be trusted or whether it is covertly ironic, creating what Wayne C. Booth has termed “unstable irony.” As a result, it remains frequently doubtful whether the emotional tenor of a given poem is one of hope or despair or both. The poet’s adamant refusal to choose between opposing possibilities - in individual poems as well as in her poetic sequence as a whole - is itself an allimportant decision. The strategy of holding alternatives in dialectical tension reflects Dickinson’s choice of a poetic existence, an existence which in various ways resembles that of Keats or Hölderlin. What makes Dickinson’s a characteristically American variant is its radically experimental quality. As she puts it tersely in one of her last poems: “Experiment escorts us last -” (1770). Her poetic experiment is as intensely American as is, in the words of Lyman Beecher, “the great experiment” of America itself. Beecher (though in many ways her antipode) would have shared the poet’s conviction: “Faith - the Experiment - of Our Lord -” (300). Possibly the most intriguing as well as the most disturbing feature for the reader of Dickinson’s oeuvre is her tendency to collapse the real and the symbolic into one. To this poet, only the symbolic is real, and reality is real only in so far as it is symbolic. Like the Transcendentalists, Dickinson categorically resists the pull of her culture to split off the realm of meaning from the world of phenomena. All facts filtered through the mind become fiction: “are not all Facts Dreams as soon as we put them behind us?” (PF22) That is why her poems tend to appear Janus-faced, looking two ways at once so that the borderline between the real and the fictional becomes blurred: “the fiction - real - / The real - fictitious seems -” (646). The ordinary concept of reality (her father’s concept in fact) is rejected in Dickinson’s poetry. Unlike Edward Dickinson, who has “made up his mind that its [sic] pretty much all real life” (L65), the daughter decides not to make up her mind. She opts for “poetry” against “prose,” i.e. for a poetic language of open possibilities. Sharon Cameron’s recent study of the fascicles, Choosing not Choosing, explores this aspect in depth. Bearing Eliot’s criticism of “a dissociation of sensibility” (64) in mind, we may interpret Dickinson’s oeuvre as her defensive gesture against a momentous and in many ways disruptive development of nineteenth-century civilization: the 3 breaking asunder of what was up to then a relatively unified discourse into different sub-discourses such as the theological, the political and the scientific discourse. The modern bifurcation into two competing discourses - the exact discourse of natural science and the plurisemantic discourse of art (Geyer) - was already well under way in Dickinson’s lifetime. In her poetic work she boldly set out to create a counter-language in which “thought” - as for Donne - could once again be “an experience” (Eliot 64). Reader Response: a Test Case From the standpoint of reader response theory, Dickinson’s insistence on the symbolic potential of poetic language is beset by considerable problems. “There came a Day at Summer’s full,” (322) is an especially challenging example that serves to demonstrate the difficulty of creating ‘significance’ (in Hirsch’s sense) from a text whose ‘meaning’ seems rather elusive. The poem has proved recalcitrant to exegesis, and its interest lies not least in the strongly divergent interpretations that the verse has elicited from a number of Dickinson scholars. Both Chase (158-59, 243) and Anderson (168) find the verse too “intangible” and too “obscure” for the reader “to share in the anguish.” Biographical, theological, psychological, existentialist and cultural readings compete with each other, and even a fine scholar such as Robert Weisbuch censures Dickinson’s “too easy denial of death's terrifying finality” (90). Not until Franz H. Link’s superb article ”Emily Dickinson: Kunst als Sakramant” do we come across an interpretation that does full justice to this exquisite poem (163-65). For Link, the poem enacts a sacramental sacrifice that in poetic language anticipates the future experience of a transcendental reality. Apart from Link and with the exception of Budick (212-23, 227-28), Harris (23-34) and St. Armand, who links this poem to “the Mystic Day (Nature) and to Transcendental Liturgy” and who detects in it “many High Anglican and Oxford Movement resonances” (132 et passim), the poem has found relatively few interpreters after 1976 (Duchac and Dandurand, vide index). A reappraisal will therefore be in order. There came a Day at Summer’s full, Entirely for me I thought that such were for the Saints, Where Resurrections - be - (variant: Revelations) The Sun, as common, went abroad, The flowers, accustomed, blew, As if no soul the solstice passed (variant: While our two Souls that) That maketh all things new - (variant: which) The time was scarce profaned, by speech The symbol of a word (variants: falling, figure, symbol; the last is underlined) Was needless, as at Sacrament, The Wardrobe - of our Lord Each was to each The Sealed Church, 4 Permitted to commune this - time Lest we too awkward show At Supper of the Lamb. The Hours slid fast - as Hours will, Clutched tight, by greedy hands So faces on two Decks, look back, Bound to opposing lands And so when all the Time had leaked, Without external sound Each bound the Other’s Crucifix We gave no other Bond - (variant: failed) Sufficient troth, that we shall rise Deposed - at length, the Grave To that new Marriage, Justified - through Calvaries of Love - (322) The poem’s thematic kernel is admittedly hard to grasp. There is no stabilizing semantic or tonal center, and the reader remains perplexed as to the envisaged situation. Does the verse deal with a biographical experience? With a lovers’ tryst, perhaps? If it does, is the “Other” a man or a woman? Rebecca Patterson opts for Kate Scott (175-78, 359) whereas Robert L. Lair prefers Charles Wadsworth (61-62). But why not Samuel Bowles or - as Smith has plausibly argued (38) - Sue? Other critics interpret the meeting as an entirely imaginary event. Richard B. Sewall, as always, gives a balanced account stating that the experience - whether real or fictitious - is “in essence” Dickinson’s (552-53). The superimposition of lover, self, soul, death and Christ makes disambiguation difficult; the various layers uneasily coexist in the poem, all contributing to its total effect. Several thematic signposts hint at an inner experience of extraordinary intensity, an experience for the sake of the lyrical self alone: “Entirely for me -”. The cyclical processes of nature are contrasted to the soul’s atemporal ecstatic moment. In the two fair copies, Dickinson has replaced “our two souls” with the hypothetical phrase “as if no soul” - a change that removes the poem’s setting even further from a real-life event. In fact, the expression “our two souls” would have given the poem a different direction altogether. The poet’s use of synecdoche and metonymy (“greedy hands,” “faces on two decks”) intensifies the symbolic quality of the dramatic encounter, emphasizing its spiritual significance. As in many other poems, Dickinson employs a concrete situation (the meeting of two boats) as a springboard to enter the realm of the symbolic. It is on the plane of symbolism, then, that the associative potential of words comes into full play, although the anchor to concrete reality is never fully cut. On the syntactic level, the verse exhibits a marked preference for juxtaposition and parallelism with the logical and temporal connectives omitted. This fact alone should make us hesitate to contrive a chronological scenario of narrative events. The expression "Summer’s full" evokes a moment of fulfilled presence. However, this climactic moment is at the same time a turning point; although the sun appears to stand still at the "solstice" (lat. sol-sistere/stare), it is about to start its retrograde movement into winter. The passing of the solstice 5 (with a pun on “soul”) “which maketh all things new” throws into relief the apocalyptic quality of the experience. The poem, we note, renders a liminal moment by crossing spatio-temporal as well as semantic boundaries. The lyrical self’s passage from life through death into an existence of renewed meaning bears comparison with Eliot’s “point of intersection of the timeless / With time” in Dry Salvages. The subtext of Revelations and other biblical passages has always been remarked on by critics, though few have bothered to address the change of meaning implied by Dickinson’s use, namely the turn from a historical millennial expectation to an experience that describes the soul’s inner potential for selftranscendence in terms oscillating between time and timelessness. John F. Lynen’s insight into Dickinson’s manner of collapsing presence and eternity (133) is helpful here. “Eternity” for Dickinson as for Blake is “obtained - in Time” (800), it is achieved now or never, and yet, as an experience of the numinous this ‘now’ is itself part of eternity. Finite life is our unique chance to experience the eternal and in that sense life is eternal. As I shall argue below, this idiosyncratic feature of Dickinson’s poetry is based on her tactics of semanticizing temporal typology into atemporal poetic inference. The overall tone of the poem is one of profound ambivalence. The verse starts out in rapturous exultation and continues through a sense of ecstatic fulfilment, only to end in feelings of intense agony - itself the precondition for the lyrical self’s trust in love’s final victory over death. In its emphatic end-position, the oxymoronic phrase “Calvaries of Love -” not only keeps the emotional tenor in suspense, but the plural form - besides stressing the ceaselessness of pain - also hints at the fact that Calvary is understood here as a universal human experience. Reinforced through a reversal of perspective, the meeting proves at the same time to be a parting, a counter-theme that brackets the emotion of ecstasy with its opposite: “despair.” Indeed, paradox (time/timelessness, death/resurrection, Eros/Thanatos) governs the poem throughout. The dialectical yoking of ecstasy and despair is, of course, fundamental to Dickinson’s work, which often focuses on what one poem calls “a perfect - paralyzing Bliss - / Contented as Despair -” (756). It is this strangely self-contradictory experience that the poet repeatedly praises as the “One” supreme “Blessing” (756) of her life. The latter part of this essay, it is hoped, will help to clarify this crux. Although the verse exploits symbolical language to the full, the focal moment is one of wordlessness. “The symbol of a word” is deemed a superfluous dress, useless as vestments worn during the Lord’s Supper. Indeed, words would “profane” the sacramental event. Concomitantly, language admits to its own impotence; the silent center hints at the poet’s self-defeating attempt to express something that cannot be expressed in words (except “slant”-wise). We are faced here with what Jay Leyda has circumscribed as Dickinson’s “omitted” center (I, xxi), Sharon Cameron as the poetry’s “ineffable” and unrepresentable center (4, 26-29), and Gary L. Stonum as its unrecoverable deep structure (30). The Romantics have of course always been aware that there is no direct analogon for 6 innerness. Paradoxically enough, in order to give form to such innerness words are needed, but what the words try to convey is out of reach. In A Defense of Poetry Shelley mourns the paradox that the process of wording (which is an act of objectification and reflexion) ineluctably implies the loss of the experiential moment (443). This is at once the perennial problem and the challenge of all lyric poetry. The experience itself may be characterized as a ‘rite of passage’: death and rebirth in one. In this context it is worth remembering that Dickinson adapted “the final stanza to honor the memory of Mrs. Dwight who had died the preceding September” (Johnson I, 252), thus distancing the poem from a specific biographical experience. The intensity and uniqueness of feeling is rendered in religious language; in fact, what is expressed in this poem is a religious experience (Link 164). Terms like “Saints” (possibly an allusion to the Puritan ‘saints’ as opposed to the lyrical self, a ‘stranger?’) and “Resurrections” (variant: “revelations”) are appropriated by Dickinson to express the soul’s ecstatic “Transport” (a ‘conversion experience’ of sorts). The motif of the seal is borrowed mostly from Canticles and Revelations where - in conspicuous contrast to the poem’s ambiguities - it denotes a mark that guarantees man’s eventual recognition by God and his acceptance into heaven. The collocation “Sealed Church,” for which there is no exact biblical parallel, has always puzzled readers. On a strictly psychological level, Cody variously understands it as “a symbol for a woman who is taboo as a sexual object,” as an expression of the need for a “mothering” male, and possibly as a biographical hint that the other person was a woman (147). From a theological angle, J. V. Cunningham points out the element of self-justification through love and suffering and he notes the striking absence of Christ’s mediation. Cynthia Chaliff, by contrast, stresses the important role of the Imitatio Christi motif in this and other love poems (101-02), and St. Armand, finally, interprets “The Sealed Church” as “an extreme expression of Calvinist exclusionism,” pointing to affinities with American Perfectionist movements. Furthermore, the expression evokes Emerson’s “inner church,” but Dickinson also plays on the multiple meanings of “sealed” in the sense of ‘self-enclosed,’ ‘secret’ and ‘designated by’ (or ‘dedicated to’) God. The act of communion takes place in a moment of timeless time, a nunc stans (“Permitted to commune this - time -”); it is at the same time a moment of self-transcendence and as such a preparatory lesson for “the marriage supper of the Lamb” (Link 164). These and other biblical passages are all radically interiorized by the poet and thus wrenched from their original meaning. Nonetheless, the theological content of these elements is not destroyed; it is rather subsumed into the larger significance of poetic thought. There is a brief effort in stanza five to arrest the ecstatic moment (“clutched tight”), but in stanza six the inevitable is accepted: “Each bound the Other’s crucifix.” In addition to a variety of biblical subtexts, there are several literary and painterly models for Dickinson’s image (some with an erotic content), but the crucial point in these verses is the covenant of love between the mortal self 7 and the spiritual Other. The element of reciprocity is intensified by a cluster of words expressing bonding. The symbol of the cross (“Each bound the Other’s crucifix -”) embodies the poem’s central paradox. The word “crucifix” refers back to “Calvary,” but it also evokes ‘crucifixion’ and - owing to the line’s mirror-like structure - indirectly hints at the persona’s self-crucifixion. On the basis of the poem’s religious quality (and neglecting the element of selfreflexivity), it could be argued - as some critics have done - that the dramatic encounter takes place between Christ and the soul; even from such a perspective, however, it cannot be denied that we are witnessing a spiritual drama that emphatically recenters the exemplary Christian paradox within the lyrical self - at once a radically ‘protestant’ and a poetic gesture (Hagenbüchle, Emily Dickinson 207-310). The final stanza once again reverses the perspective in that the pledge of love appears now strong enough to overcome death and separation. The expression “that new Marriage” has biblical - even mystic - resonances, deflating the conventional social ceremony (nor should one forget that in protestant theology marriage is not a sacrament). The word “troth,” in turn, displays a wealth of connotations. Besides alluding to ‘faith’ and ‘truth’ (Shakespeare), it also evokes ‘betrothal’ and - most importantly - ‘betrothed’: “Betrothed - without the Swoon” (“Title divine - is mine!” [1072]). There is, finally, a clear reference to the 1662 Book of Common Prayer (“I plight/give thee my troth”), but Dickinson typically suppresses the subsequent element of corporality as found in the Anglican marriage vow. The element of eventual justification through suffering is a pervasive theme in Dickinson’s work. Accordingly, the resurrection mentioned in the final stanza is seen as the divine gift expected in exchange (even as payment) for the lyrical self’s suffering of pain and death. However, “the troth, that we shall rise -” remains unspecified: it is here and nowhere, now and never. In other words, this eschatological event is situated in the realm of “Possibility” alone (Hagenbüchle, “Precision and Indeterminacy” 49-50, “Sign and Process” 152-53). The expected fulfilment of the promise is one of poetic inference, and to that extent the future is already incorporated in the present. What we discover in the poem, then, is neither an “omitted” nor an empty center. It is rather a deliberately created emptiness, a semantically open interspace implying potential fullness: “not yet a voice, but a vision.” (L 1035) The question remains, as it always does with Dickinson, in how far the movement of poetic language is capable of taking over the burden of the biblical word. The poem is the locus for selftranscendence but no transcendence in a metaphysical sense is forthcoming. The poem’s dominant motif of meeting as departure is of course a topos in Romantic (and Victorian) poetry, Goethe’s “Willkommen und Abschied,” Byron’s “When We Two Parted” or Tennyson’s “Love and Duty” being wellknown examples. In Dickinson’s verse, the Romantic motif has not only acquired a sacramental quality (Link 129-189, esp. 164), but the expectation of an ultimate 8 union is firmly rooted in the Puritan ‘covenant’ principle, though the lyrical self’s pact is now with the divine alter Ego. The soul’s act of entering into a solemn “Compact” with itself is the very basis of Dickinson’s poetic faith, but it is also a source of unending pain: “Because the Cause was Mine - / The Misery a Compact / As hopeless - as divine -” (458). Whereas the original ‘covenant’ relied on the promise of a transcendent fulfilment, the poet’s “Compact” seems to have lost its scriptural basis as divine guarantor: it is now a self-reflexive and truly ‘self-consuming’ act of the mind. The Search for Self What the reader encounters in the above text is clearly not the real-world Dickinson; rather, it is the poet’s experiencing self and her inquisitive (often puzzled) mind that speculates on these experiences and tries to come to terms with them. It is this speculative quality that leaves the question of a biographical experience unanswered and unanswerable, thus rendering it largely irrelevant. Following Dickinson’s own hints, critics have repeatedly suggested that her “Flood subject” is “Immortality,” but it would probably be more accurate to claim that it is the poet’s effort to (re)create herself as a subject in her work since the social world allowed her creative mind and her hunger for self-exploration no viable alternative. What we discover in her poetry is a lyrical “I” in search of a “self.” Heiskanen-Mäkelä was among the first to interpret Dickinson’s experience of “terror” as a conversion to herself (17-18), as an act of poetic rebirth: “To live, and die, and mount again in triumphant body, and next time, try the upper air - is no schoolboy’s theme!” (L184) It is through the poems, then, that Dickinson attempts to find a place in her culture. As the poems and letters tell us, young Dickinson tried out various alternatives, such as the Romantic or the Transcendentalist self, and her Byronic role-playing proves that she experimented with all these options. However, the frame in which Dickinson first sought to understand herself was the Christian narrative. Claudia Yukman has demonstrated how the poet at once employs and breaks the “eschatological frame” that she invokes (92). This is done both in anger and in sadness: in anger because the orthodox Christian framework restricts the creative freedom of her quest, in sadness because the rejection results in bleak “liberty” (281), in the loss of a metaphysical home, in what from today’s view might be called a ‘decentered’ existence. No wonder, the lyric persona feels “homeless at home” (1573). In some of the early poems Dickinson still seems to accept an eschatological view. “On this wondrous sea” (4), for example, ends with the exultant lines: “Land Ho! Eternity! / Ashore at last!” This piece, along with “Sleep is supposed to be” (13), ranks among the most striking examples of the poet’s chiliastic optimism. But even in these verses one feels the tug away from an emblematic style towards a symbolic mode. To claim that Dickinson could not accept the “Christian narrative” is insufficient, however; what she could not accept is the consequence that this view would have entailed for her language. 9 Biblical literalism (in the Calvinist-Puritan strain), as Dickinson recognized, would rigorously foreclose the open-endedness of her poetic faith: “to believe [. . . ] would foreclose Faith -” (912). Images and symbols, as Emerson repeatedly criticized, suffer from becoming fixed in theological doctrine. To Dickinson, ideological frames of any sort - those of practical life no less than those of scientific discourse - fatally block the free play of the mind and along with it the exploratory movement of poetic language. The poetic discourse alone is resourceful enough to power her quest for self-transcendence. Although the poet could not find her home in a Puritan self, she might have found it in Romanticism or in Transcendentalism - and to a degree she did. What she could not accept was Emerson’s hermetic notion of a correspondence between the Me and the Not-Me. Nor could she assent to Wordsworth’s (however precarious) balance between self and world, and his serene sense of continuity was alien to Dickinson for whom the discontinuities of experience privileged difference over identity (910). It is symptomatic that the returning self in one of her poems (609) no longer finds the earlier self at home. Self-alienation and self-transcendence came to make an uneasy but inevitable pact in her oeuvre. Still, the Romantic self did have its attractions for her, especially the notion of a poetic existence along with a sense of infinite surmise. And in Shelley’s A Defense of Poetry she encountered a concept of language and of poetry with which she could largely identify: the poetic word as the incarnation of spirit (444). At Home in Language Nowhere in Romanticism or Transcendentalism, however, do we find anything approaching the intensely symbolic power that Dickinson accords the word. The poet’s ‘linguistic turn’ is not merely a consequence of the Romantic movement, it is in some profound way a return to the very sources of her own culture. Without the central position of the biblical ‘Word’ in Puritan New England, the poet’s religious conception of poetic language would have been unthinkable. It is in the very act of ‘bearing the word’ that she finds her truly feminine self - and what a powerful self. In her symbolic language Dickinson could enjoy the creative liberty of mind that transcends all ideology and all stereotype, not least stereotyped gender restrictions. Whenever she exploits conventional Victorian imagery it is plainly to put pressure on social clichés. It is in poetry, then, that Dickinson found her home at last. Both in the letters and the poems one may follow the poet’s attempt to constitute her self in language. Unlike Whitman’s self, as Agnieszka Salska has masterfully shown, Dickinson’s is a remembering self (35-64), though it is also a self of grand expectations. That is precisely why it is a very precarious self in need of continuous re-creation, based as it is on the symbolic movement of poetic language. To Whitman the word is a living thing: self, word and world fuse in a process of endless concrescence. For Dickinson, no such concrescence occurs. With her, by contrast, the poetic word assumes an autonomy that anticipates Mallarmé’s symbolist concept of language by more than a generation. In fact (as 10 I shall demonstrate elsewhere), Mallarmé exhibits neither the metaphysical boldness nor the epistemological lucidity of Dickinson’s poetic method (cf. Cambon 33; St. Armand 283-84). Dickinson herself has emphasized the equal - if elevated - status of words: “I lift my hat when I see them sit princelike among their peers on the page.” And they really do sit on the page in their full individuality. In the poem “There’s been a death in the opposite house” (389), the line: “There’ll be that dark parade” is spatially separated from the other lines with the black words actually parading before the reader on the white sheet. Looking at an individual word, Dickinson comments on its shape: “I look at its outline til [sic] he glows as no sapphire” (qtd. by Sewall, Lyman Letters 78). Words with Dickinson not only possess a transcendent quality (the gates of Zion are made of sapphire), but they are also gendered masculine: words are as much in her power, as she is in theirs. Explicitly or implicitly, most poems by Dickinson are concerned with the testing of language. Romantic poetry in general is intensely self-reflexive, but the Romantics do not exploit language to its breaking point the way Dickinson does. Her testing has a remarkably modern quality, although it stops short of the metapoetic explicitness of a Wallace Stevens, Conrad Aiken, and T. S. Eliot. What Dickinson is particularly interested in is the liminal or threshold quality of language, a quality in which the modernist poets have little or no trust. Writerly Style Critical consensus has grown recently that Whitman’s stylistic devices look tame - even conservative - in comparison with Dickinson’s Modern Idiom (Porter). Unlike Whitman’s expansive syntax, her tightly structured poetry forces readers to radically change their reading habits. Instead of passively enjoying Dickinson’s verse, we are called upon to actively cooperate. The poet’s handling of compression and juxtaposition (occasionally approaching surrealist montage) radically increases semotactic indeterminacy, thwarting the reader’s desire for univocal meanings; in "Four Trees - upon a solitary Acre -" (742) juxtaposition and with it the question of relation - is raised onto the level of ontological uncertainty. Further difficulties arise from Dickinson’s idiosyncratic punctuation, from her technique of semantic and phonic slant as well as from her method of inference. The poet’s use of paradox, her hypothetical mode and her predilection for non-finite forms present additional hurdles. Undoubtedly, Dickinson’s is a writerly, not a readerly, style. As to the modernity of Dickinson’s poetic strategies, much has been made of her sophisticated handling of prosodic and phonic devices, a field in which Judy Joe Small’s As Positive as Sound has broken fresh ground. The hymn measure along with a relative lack of rhythmic and stanzaic experiments is responsible for the surprisingly musical quality of her poetry, a quality largely lost to modernist writers. Nonetheless, it is on the levels of syntax and semantics, as David Porter and Cristanne Miller have persuasively argued, that the poet’s most daring innovations are to be found. 11 Critics have repeatedly claimed that Dickinson is a non-mimetic writer. This needs some qualification, however. Although the poet makes almost no use of real-world (descriptive or first-level) mimesis, she does employ two other mimetic modes extensively: situational and semantic mimesis. Instead of representing the outer world as such, secondary mimesis supports formal and thematic levels within the poem itself. Situational (or second-level) mimesis renders the innerness of experiential and mental processes in situational form. With Dickinson, such situations are from the start raised onto a symbolic level. They do not function in an allegorical manner, however, since they lack the autonomy peculiar to the allegorical mode. Instead of coherent real world settings, we are offered diagrammatic situations, that is, situations reduced to bare essentials. Like other Romantics (Keats, for example), Dickinson tends to use analoga in negated form. Indeed, her poetic style is as emphatically anti-analogical as it is radically anti-allegorical (Weisbuch 40-58). From this perspective at least, her oeuvre stands outside the mainstream tradition of nineteenth-century American literature whose principal mode is insistently allegorical (Hansen 195-235). Semantic (or third-level) mimesis supports on the phonic, prosodic and iconic levels what the poem expresses on the semantic level. Unlike rhyme, metre and rhythm, Dickinson’s use of iconicity (the spatial positioning of words on the sheet) has not yet found the attention it deserves, one reason being that it is all too often lost in Thomas H. Johnson’s transcription (Smith 19-20, 67-69, 82-85). What presents the most serious problems to the reader is neither first- nor thirdlevel mimesis; it is rather the poet’s preference for diagrammatic mimesis to the virtual exclusion of real-world (or descriptive) mimesis. As St. Armand and Monteiro have amply documented, real-world elements (often in the form of emblems) are always strongly present in the poems, but they rarely constitute a consistent real-world setting. Remaining for the most part “sceneless” (Weisbuch 15-19, 23-39), the poems rather defy the reader’s wish for visualization. Dickinson’s diagrammatic mode (minus its symbolic quality) points forward to imagistic techniques of twentieth-century poets. In many ways, as HeiskanenMäkelä has perceptively observed, Dickinson’s style (especially her late style) resembles “the calligraphic hands of the old masters of Chinese and Japanese art” (186). Most of all, it resembles the Koans and the paintings of the great artists of Zen Buddhism (Hagenbüchle, “Sign and Process” 152). In these artworks Charles Anderson could have discovered parallels more congenial to Dickinson’s verse than in American abstract impressionism or in expressionism and cubism (36). Semantic Shift Dickinson is a great leaver-outer, but the reader - as Suzanne Juhasz rightly warns (93) - should not yield to the temptation simply to fill in the gaps. The real challenge of Dickinson’s style is for us to co-create the poem by actively 12 pursuing the semantic processes instigated by the text, to make explicit what is only implicit in her verse, to deliver “the undeveloped freight” (1409) of Dickinson’s words. This is more easily said than done. A number of contributors to the impressive collection of essays Teaching the Poetry of Emily Dickinson are at pains to point out that the poet’s metaphors are not ordinary metaphors. One could even go a step further and argue (as I have done) that most of her metaphors are metonymically constructed. Unfortunately, the Jakobsonian distinction between metaphor and metonymy has turned out to be a dubious one. The biaxial analysis - overly formal as it is - has recently been challenged by Ohnuki-Tierney (159-62). Genette has shown conclusively that all verbal figuration of necessity partakes of both modes: metaphors rely on metonymic processes just as much as metonyms depend on metaphoric operations. What is now in the center of scholarly interest is the interaction, the play between the tropes. In his seminal essay on “polytropy,” Paul Friedrich convincingly argues that there is no clear-cut hierarchy among the tropes. None of the macrotropes (ten in his view) is a subtype of or can be derived from any other: “Their categories constitute a theoretically open-ended and constantly changing set” (23). Dickinson’s poetry displays a variety of tropes, metaphor and metonymy among them. One of her metaphoric practices is synaesthesia, a favorite device with Romantic poets. However, as Schullenberger has contended, synaesthetic tropes with this poet tend to be displaced and “discordant” (100). Indeed, Dickinson’s poetic style seems to incline towards metonymy rather than metaphor (Hagenbüchle, “Precision and Indeterminacy” 33-45). Instead of relying on Jakobson’s binary scheme, I now want to focus on what I consider to be one of Dickinson’s most intriguing semantic procedures: ‘semantic shift.’ By semantic shift (which includes traditional metonymy) I mean the poet’s tendency to select elements that as clues point to other elements as further clues, a method of reasoning called “abduction” by the American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce, the founder of Pragmatism and of the science of semiotics (Kent 176-79). Peirce’s definition of “abduction” is ideally suited to clarify Dickinson’s method of semantic shift. As Weisbuch has noted in his chapter on the poet’s “Quest Fiction,” one of her key words is “guessing” (1518). Guessing is an integral part of Dickinson’s hypothetical mode of “inference” and “conjecture,” concepts which are in turn related in many of her poems to the notion of “risk.” Guessing, conjecture and risk are all attributes that Peirce uses to define “abduction” (Bonfantini 128-33). Unlike (habitual) induction and (logical) deduction, “abduction,” we are told, is “after all, nothing but guessing" (qtd. by Sebeok 49). But the kind of guessing Peirce means has a holistic quality; it is like a felt thought. As such it is already present at the lowest level of creativity, namely at the level of sense impression (Sebeok 19). The act of attribution, Peirce explains, has the function of a hypothesis that is determined “by the constitution of our nature” (qtd. by Bonfantini 129), and it is man’s nature that makes this type of guessing “not altogether hopeless” (qtd. by Sebeok 17). 13 Peirce’s concept of “abduction,” we may provisionally conclude, is a type of inference that implies a high degree of risk. Such risk is a quality fundamental to all heuristic processes. And what is the nature of Dickinson’s poetry if not heuristic? In The Sign of Three: Dupin, Holmes, Peirce the term “abduction” is used to explain certain semantic procedures characteristic of the detective story, a genre exemplified in this collection by the narrative practice of Edgar Allan Poe and Arthur Conan Doyle. As the preface states, it is the purpose of the contributors to elucidate the scientific and poetic method of inferential discovery (ix). Much like a detective (Bonfantini 127), the reader of a Dickinson text acts as a solver of riddles. Dolores Lucas has applied the riddle model to Dickinson’s poetry in general and to the definition poem in particular in which the act of inference (as “abductive suggestion”) plays a crucial role. Let me now briefly exemplify Dickinson’s use of semantic shift. How can we define the wind? By means of metaphors, for instance: “the bawdy wind that kisses all it meets” (Othello). Further: the wind as heavenly babe (Der Wind, der Wind, das himmlische Kind), the wind as messenger, as warrior, and so forth. But Dickinson tends to prefer another strategy. To her it is “the vane” (the device that points the way the wind comes from) that “defines the wind.” (L830) The vane does not function as a metaphor with two poles; instead it operates as a semantic pointer inviting the reader to go in search of what is being pointed at. Again, “And a Suspicion, like a Finger / Touches my Forehead now and then” (959) is not so much a simile as a pointer hinting at the source of what creates the suspicion in the first place. One might speak with Juhasz of “metaphors [. . .] as action” (87) or of performative metaphors in that the “finger” at once points out and enacts the semantic process going on. In much the same way, the “horses’ heads” (712) in Dickinson’s ‘last ride poem’ point towards eternity. While the horses in their substantiality appear to be carrying the speaker towards the grave, it is their heads that (synecdochically) point a different way. And so the poem ends on the paradox of death and immortality, both sitting simultaneously at the speaker’s side. In an early letter to her “Dearest of all dear Uncles,” Dickinson humorously complains: “people will get hit with stones that I throw at my neighbor’s dog - [. . .] but they insist upon blaming me instead of the stones [. . .] such things should not be permitted. [. . .] Life isn’t what it purports to be.” (L29) The same semantic relation - although in inverse form - can be found in the verse “I love the Cause that slew Me” (925) and again in the lines “We will not drop the Dirk - / Because We love the Wound” (379). The “Dirk” seems at first sight to function as a metaphor for the painful memory of loss; but on closer inspection it is not the dirk qua dirk that is essential to our understanding but the causal nexus between “Dirk” and “Wound” with the wound as a reminder of the dirk’s power to hurt and give pain. 14 Types of Semantic Shift The eminent rhetorician Heinrich Lausberg in Elemente der literarischen Rhetorik distinguishes two types of tropes: the Grenzverschiebungs-Trope and the Sprungtrope (64). Unlike the Sprungtrope that finds its vehicle in an unrelated semantic field (‘jumping from one to the other’), the Grenzverschiebungs-Trope (which includes the synecdoche) is a figure of speech that by Lausberg’s definition shifts the boundary, moving the meaning from one semantic field to an adjoining field. It is easy to see that Lausberg’s Sprungtrope is by and large identical with the traditional ‘metaphor,’ whereas the Grenzverschiebungs-Trope resembles Jakobson’s term ‘metonymy’ and its principle of contiguity. The latter, Lausberg suggests, functions essentially on the basis of relations that hold in reality; the former (the Sprungtrope) is primarily but not exclusively - a semantic relation. The boundary between the two terms is therefore a fuzzy one. Lausberg’s definition is attractive for two reasons: it undercuts Jakobson’s binary opposition between metaphor and metonymy and, most importantly, the Grenzverschiebungs-Trope lends itself to a historical perspective. Extending the rhetorical Grenzverschiebungs-Trope into the historical dimension allows us to distinguish between two types of semantic shift: the synchronic type on the one hand and the diachronic type on the other. The synchronic type not only comprehends Dickinson’s use of metonymy proper but also her idiosyncratic shifts between different kinds of discourse. Theological, political, legal, commercial, scientific and everyday discourses are all turned against themselves in that the poems move the systematic terms into the realm of the symbolic. In this way, the poet counters instrumental thought, undermines socially sanctioned preconceptions, lays bare their pretension to truth and criticizes their underlying value systems. In the poem “Arcturus is his other name” (70) poetic discourse is played off against scientific discourse. This is an obvious example, admittedly, but it illustrates the fact that scientific discourse (in competition with religious and political discourse) is about to gain a dominant position in mid-nineteenth century American culture - an ominous development in Dickinson’s eyes. In poems like “I never lost as much but twice -” (49) or “I asked no other thing -” (621) social, theological, legal and commercial terms are all marked pejoratively to express the poet’s anger at her existential plight. Theological discourse, in particular, is counterpointed to poetic discourse in the poem “The Lilac is an ancient shrub”: “But let not Revelation / By theses be detained -” (1241). The true “Scientist of Faith” is in fact the poet who has only begun “His research.” The tension between theological, legal and poetic discourse is also manifest in the letters, particularly in Dickinson’s value-laden correspondence with Otis P. Lord. In a note to her nephew “Ned” the poet clowns: “Deity will guide you - I do not mean Jehova -” (L1000). And on the occasion of Miss Mather’s engagement she sends her a letter of congratulation, teasing: “May it have occurred to my sweet neighbor that the words ‘found peace in believing’ had other than a theological import?” (L1032) Unquestionably, the poet’s 15 semantic shifts reveal an intense awareness of what Michel Foucault in Les mots et les choses has unmasked as the struggle for social hegemony and the claim to power among a culture’s rivalling discourse modes (373 et passim). Nor should it finally be overlooked that Dickinson’s critique is also directed against the dead conventions of poetic discourse itself, in particular against ideologically motivated “symbolic reduction” (Budick 100-162). It is the type of diachronic shift, however, that most deserves our scrutiny. From the beginning, critics have recognized Dickinson’s way of maneuvering historical vocabularies for subversive purposes. Calvinist-Puritan terms (“immortality,” “crucifixion,” “state,” “election”), Romantic terms (“nature,” “myth,” “surmise”), social terms (“father,” “bride,” “wife,” “gentlewoman”), political terms (“majority,” “rebel,” “mutiny,” “revolution”) are all tested against the touchstone of poetic discourse. Not infrequently, the critique is pressed home through the revitalization of a given term’s etymological meaning as in “grace” (theological ‘grace’ versus poetic gratia as the transcendent call of beauty), “philology,” “crisis,” “civilization” and the like. Dickinson’s adaptation of the New England notion of “a waste howling wilderness” to her own sense of spiritual waste, of “Blank - and steady Wilderness -” (458), is an especially striking example that mirrors the shift from Puritanism to mid-nineteenth century American culture and, more particularly, exposes the poet’s loss of a metaphysical basis. Dickinson’s appropriation of the religious term “soul,” more perhaps than any other, highlights her choice of existential and poetic autonomy, but it also betrays her acute sense of alienation as the price to pay for her insistence on the self’s independence. Besides the Puritan conversion experience, beautifully instanced by “I’ve heard an Organ talk sometimes” (183), it is the Romantic (and Transcendentalist) experience of the sublime that displays subtle but profound mutations in Dickinson’s work (as we can learn from Dihl, Stonum and Loeffelholz). The frequently anthologized “There’s a certain slant of light” (258) is a case in point. The poem documents the silencing of the biblical voice along with the loss in the traditional sense of a religious calling. The expression “Seal Despair” not only questions the literal promise in Revelations pledged to all those who carry the seal of God on their foreheads, but it also manifests the infinite distance between man and God. Along with the oxymora “heavenly hurt” and “imperial affliction” it underscores the poet’s estrangement from her Puritan heritage. The self-contradictory quality of the experience stresses the painfully transient encounter between the generic “we” (lyrical self and implicated reader in one) and an unspecified divine presence, and at the same time subverts the religious basis of the numinous. As a result, the poem removes ‘the Dickinson sublime’ from Wordsworth’s “egotistical sublime” no less than from Poe’s “negative sublime” (Weiskel). Although the epiphanic moment still occurs, it can now only be grasped in terms of loss and pain. It is not least Dickinson’s method of semantic shift - both synchronic and diachronic - that throws into relief the intensely dialogic quality of her poetry. The dialogue may be carried on in the form of dispassionate inquiries, but the 16 debate can also turn angry, especially if social and ideological presumptions are under attack. Through her technique of semantic shift the poet manages to question the value system of her own society and to subvert the very basis of Victorian culture. The Arrow of Meaning Metaphors can be defined as semantic processes that function in terms of mapping, that is, of a semantic exchange between closed fields of meaning. Dickinson’s semantic shifts, by contrast, display an element of directiveness missing in metaphoric tropes. Although the poet sends the reader forth into the realm of the unknown, she invariably sets the direction. Such directiveness is central to her work: it generates meaning without delimiting the meaning. Poe, too, is well aware that all thinking is processual, that it stops when settling down on ‘terms’ (Poe 488, 498-500), but with him the movement seems to have lost its vectorial quality. Not so with Dickinson. The inferential gestures are energized by the poet’s double stimulus of love and death, the one challenging the other: finitude as the spur of self-transcendence. Starting out from real-world facts, the directional arrow moves the reader towards a symbolic realm with an attendant increase in meaning. Even the simplest poem testifies to this movement from facts to living symbols. In her poem “By my window have I for scenery / Just a Sea - with a Stem -” (797) the word ‘Pine’ is insufficient to the lyrical self because it refers (through an act of classification) to the kind of tree that the commonsensical farmer views as a practical thing at hand. To the perceiving mind, however, the tree’s meaning does not stop there. As an object, the tree is bracketed in a kind of “phenomenological reduction” (Hagenbüchle, “Precision and Indeterminacy” 38). What is focused on is its effect on the perceiving mind. From this angle, the tree in front of her window reveals its true significance as “a ‘Fellow / Of the Royal’ Infinity?” (‘academically’ unnamable!), hinting at God’s creative power. The synecdoche “Stem” and the synaesthetic use of “Sea” for sky (along with the understatement “Just a”) combine to defamiliarize - and devalue - referential language. In a second epoche, sense impressions are reduced to bare, but semantically rich, essentials with the words “Stem” and “Sea” functioning as semantic pointers, referring the reader to poetry and eternity, respectively. Dickinson’s raids on the inarticulate remain indeterminate and in their result uncertain, but the directive potential is powerful enough to create meaning out of absence. The inferential method of these raids is not based on referential presupposition but - that is their secret - on semantic entailment. With the possible exception of Hopkins, Dickinson’s oeuvre presents a higher degree of semantic implication than that of any other nineteenth-century writer. Implication also accounts for the fact that semantic inference and the temporal dimension of the future can no longer be clearly distinguished. Meaning in terms of semantic implication is both atemporal and future-oriented, in one word: directional. Feidelson was right in claiming that the American variant of nineteenth-century 17 symbolism cannot be understood without its grounding in Puritan typology (8889, 100-01). With Dickinson, in particular, the temporal dimension of the original antitype (as God’s millennial promise) can still be sensed, although it is now interiorized, subsumed in the poetic principle of inferential thought (Hagenbüchle, “Sign and Process” 142). The utopian quality of her poetry fuses past, present and future into what might be called Dickinson’s ‘apocalyptic present.’ This is not a grammatic tense, of course, but a fictional mode of time; time not as an aspect of the spatio-temporal world but as a state of consciousness coextensive with the movement of poetic language. Crossing Boundaries Critics rightly claim that the essence of Dickinson’s work is quest. More precisely, it is a linguistic quest that focuses intensely on semantic boundaries. Indeed, one of the allurements (but also one of the difficulties) of her poetry is its liminal or threshold quality. What I wish to draw attention to here is the intriguing fact that spatio-temporal boundaries tend to function both as semantic blockers and as stimulants. In the poem “Our lives are Swiss” (80), for example, “Italy stands the other side!” while God’s “siren Alps / Forever intervene!” so that the land of southern warmth - the object of desire - comes to denote to the lyrical self all that is forbidden. Yet the very fact that it is forbidden transforms the unattainable land (with Moses as biblical prototype) into the ‘Promised Land.’ Using a Hegelian terminology, we might distinguish between Grenze as stressing human finitude and Schranke (‘crossing-gates’ or ‘gateways’) as emphasizing the act of crossing and transcending boundary lines. As all readers know, Dickinson’s crossings do not always succeed, in fact, they often fail, but they invariably bring into play symbolic language as the sphere of the possible. Let us briefly examine what happens at these boundaries. Broadly speaking, we may signal out three types of semantic processes: boundaries generate meaning, they cause meaning to break down and, third, meaning is left suspended in paradoxical oscillation. In the first case, the boundary line provokes the mind to cross and transcend it, to project itself into the yet unknown. Though we know nothing certain about the realm called “Paradise” (except its loss), we can “infer” its “vicinity” “By it’s [sic!] Bisecting / Messenger -” (1411), namely death: the ultimate frontier (marked here iconically). From a strictly theological point of view, however, such crossings appear as acts of irreverence, even as sinful transgression. No wonder they are often accompanied by feelings of guilt. One of the “Eastern Exiles” who “strayed beyond the Amber line / Some madder Holiday -” (262) is plainly the poet herself. The second type is found in poems like “I felt a Funeral, in my Brain” (280), in which the safety plank of rational thought breaks down so that the speaker falls into the abyss of meaninglessness - a mise en abîme of sorts (Deringer and Hagenbüchle 196-99). The third type is of special interest to us since Dickinson uses a method that exploits the age-old device of paradox but in its epistemological explicitness anticipates modern systems theory (Schwanitz 2731). In such cases, the speaker appears to straddle the line so that it belongs simultaneously to both sides (like the figural contour of a picture puzzle). In the 18 much-admired poem “The Admirations - and Contempts - of time -” (906) we simultaneously look back at mortal life and forward towards eternity, the dividing line being the “Open Tomb” from which both poet and reader seem to gaze. From this view, man’s existence appears paradoxical: “Finite Infinity.” Dickinson’s “Compound Vision” (as it is called here) is not based on philosophical or metaphysical assumptions, it is based on the structure of poetic language itself. The above typology, abridged as it is, helps us to understand why Dickinson’s poetry always tends to bifurcate into ecstasy and despair with the paradox (or biform) bracketing the alternatives. In the last analysis, however, the poet’s semantic crossings must be understood as her symbolic enactment in language of the nation’s ceaseless drive into the yet unmapped West, rushing - as Lyman Beecher exulted - “like a comet into infinite space” (qtd. by Franklin 11). Errand into the Wilderness For this poet, the testing of semantic boundaries is a method of thought indispensable to the testing of life’s meaning (or lack of secure meanings). Like Keats she has the courage to live in uncertainties without an irritable reaching out for absolute truth. The seemingly paradoxical choice of keeping choices open in her poetry is itself a profoundly ethical act: it defends the liberty of the self against the cultural constraints of her time and, conversely, offers a last stand against the threat of nihilism, a threat increasingly visible in a culture that - as the work of Hawthorne and Melville testifies - is about to lose a reliable standpoint. Dickinson’s insistence on sheer potentiality - “The Possible’s slow fuse” (1687) accounts for much of her poetry’s semantic, perspectival and tonal ambivalence with which the reader has to cope. From this angle, Dickinson’s aesthetics proclaims itself as an aesthetics of provocation: she provoked the reader of her time, Higginson among them; she provoked language to cross frontiers and open up the realm of poetic possibility; she provokes today’s audience to pursue the complex semantic processes that her texts instigate; but most of all she provoked herself into entering terra incognita, a venture charged with existential and aesthetic risk. In fact, with Dickinson the two were one. Critics have repeatedly commented on the skeptical core of Dickinson’s art. Although skepticism is viewed by her as an alternative, both metaphysically and epistemologically, it is not her last word. Her final attitude is one of faith, faith in the creative power of poetic language. Unlike Melville, who despaired of language as a Nietzschean mask of lies and self-deceptions, Dickinson kept her faith not least because her creativity - her animus (Gelpi 299) - remained virtually undiminished to the end of her life. Nonetheless, the choice of poetry as a battlefield to test the essence of life and of selfhood - “If it contain a Kernel?” (1073) - entails its own perils. No one can guarantee that the conjectures stimulated by symbolic language will eventually be answered by something in reality. The inferential thought processes that 19 Dickinson’s poetic discourse engenders might just as well be mere fictions, the poet’s own creations - a suspicion that occasionally crosses her mind. If such turned out to be the case, the very ground of her poetry would crumble. “A word that breathes distinctly / Has not the power to die / Cohesive as the Spirit / It may expire if He -” (1651), but if the mythic “He” does not exist, her palaces will “drop tenantless;” her poetry would lack a vital center and the poetic word turn out to be a “woid” (Joyce). In other words, if the movement of symbolic language (that in turn sustains the mythic “He”) comes to nothing, all fails, and the poet’s “Vision” vanishes like a treacherous “ignis fatuus” (1551). Dickinson was painfully conscious that her home in language was far from being secure. It is this acute awareness that documents the historical turning point at which the poet is situated: the “Great Divide” between the RomanticTranscendentalist movement on the one hand and the emergence of Modernism on the other. Indeed, Dickinson resisted Modernism as much as she inaugurated it. To feel the lack of significance without a sense of sadness and of loss came to be the attitude of many a modernist and postmodernist writer, but it surely was not Dickinson’s stance. Moments of ecstasy alternate with moments when “the meaning goes out of things” and no signal comes. Such moments are moments of expansion only if outlived. (PF 49) And yet the poet was determined to keep her faith in the creative word even if the spirit she served should fail her: “So when the Hills decay - / My Faith must take the Purple Wheel / To show the Sun the way -” (766). Such a faith is unthinkable without the Puritan notion of a ‘covenant.’ In keeping her part of the “Compact” (458) with her alter ego - Eros and Thanatos in one - Dickinson achieved a measure of self-assurance that finally allowed her to cope successfully with life’s “Abyss.” It is in her poetic oeuvre, then, that the seventeenth-century vision of an “Errand into the Wilderness” (as Samuel Danforth unforgettably phrased it) has found its nineteenth-century poetic fulfilment. Without the ‘covenant’ thought and without the historic “Errand,” those prototypical New England myths, neither the poet’s boldness to confront life’s “Wilderness” nor her unflagging courage to pursue her quest would seem to have been possible. From that perspective (and as Richard Sewall pointed out long ago) the image of Emily Dickinson as a spinster trapped in a garret turns out to be totally ludicrous. Is it not amazing that the same woman who deliberately withdrew from social life had the courage to pioneer into realms we all shy back from: our mortality and the divine gift within us? To have embodied in her verse America’s westering spirit in a deeper sense than any other nineteenth-century poet is Dickinson’s crowning achievement. Authors and Works Cited: 20 Anderson, Charles. “The Modernism of Emily Dickinson.” Emily Dickinson: Letter to the World. Centenary Conference 1986. Washington: The Folger Shakespeare Library, 1986. Bonfantini, Massimo A. and Proni, Giampaolo. “To Guess or not to Guess.” The Sign of Three: Dupin, Holmes, Peirce. Ed. Umberto Eco and Thomas A. Sebeok. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1983. Booth, Wayne C. A Rhetoric of Irony. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1974. Budick, E. Miller. Emily Dickinson and the Life of Language: A Study in Poetic Symbolics. Baton Rouge and London: Louisiana State UP, 1985. Cambon, Glauco. The Inclusive Flame: Studies in Modern American Poetry. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1965. Cameron, Sharon. Lyric Time: Dickinson and the Limits of Genre. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins UP, 1979. ---. Choosing not Choosing: Dickinson’s Fascicles. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1992 (unfortunately this facinating study was not available to me at the time of writing). Chaliff, Cynthia. “The Bees, the Flowers, and Emily Dickinson.” Research Studies (Washington State U) 42, no. 2 (June 1974): 93-103. Cody, John. After Great Pain: The Inner Life of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard UP, 1971. Cunningham, J. V. “Sorting Out: The Case of Dickinson.” Southern Review 5, no. 2 (Spring/April, 1969): 436-56. Dandurand, Karen. Dickinson Scholarship: An Annotated Bibliography 19691985. Garland Reference Library of the Humanities 636. New York and London: Garland, 1988. Deringer, Ludwig and Hagenbüchle, Roland. “Amerikanische Lyrik des 19. Jahrhunderts.” Die amerikanische Literatur bis zum Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts. Hg. Helmbrecht Breinig and Ulrich Halfmann. Tübingen: Francke Verlag, 1985. Diehl, Joanne F. Dickinson and the Romantic Imagination. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1981. Dobson, Joanne A. Dickinson and the Strategies of Reticence: The Woman Writer in Nineteenth-Century America. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana UP, 1989. Duchac, Joseph. The Poems of Emily Dickinson: An Annotated Guide to Commentary Published in English, 1890-1977. Boston, Mass.: Hall, 1979. Eliot, T.S. “The Metaphysical Poets.” Selected Prose of T.S. Eliot. Ed. Frank Kermode. London: Faber and Faber, 1975. Feidelson, Charles, Jr. Symbolism and American Literature. 8th ed. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1970. Foucault, Michel. Les mots et les choses: une archéologie des sciences 21 humaines. Paris: Gallimard, 1966. Franklin, Wayne. Discoverers, Explorers, Settlers. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1979. Friedrich, Paul. “Polytropy.” Beyond Metaphor: The Theory of Tropes in Anthropology. Ed. James W. Fernandez. California: Stanford UP, 1991. Gelpi, Albert. The Tenth Muse: The Psyche of the American Poet. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard UP, 1975. Geyer, Paul. Diskurslandschaft der Moderne (forthcoming). Hagenbüchle, Roland. “Precision and Indeterminacy in the Poetry of Emily Dickinson.” Emerson Society Quarterly 20 (1st Quarter 1974): 33-56. ---. “Sign and Process: The Concept of Language in Emerson and Dickinson.” Emerson Society Quarterly 25 (3rd Quarter 1979): 137-55. ---. “Emily Dickinsons Aesthetik des Prozesses.” Wirklichkeit und Dichtung: Festschrift zum 60. Geburtstag von Franz Link. Hg. Ulrich Halfmann et al. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 1984. [A slightly shortened English version can be found in Poetry and Epistemology: Turning Points in the History of Poetic Knowledge. Ed. Roland Hagenbüchle and Laura Skandera. Regensburg: Pustet, 1986.] ---. Emily Dickinson: Wagnis der Selbstbegegnung. Tübingen: Stauffenburg, 1988. Hansen, Olaf. Aesthetic Individualism and Practical Intellect. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1990. Harris, Natalie. “The Naked and the Veiled: Sylvia Plath and Emily Dickinson in Counterpoint.” Dickinson Studies 45 (1983): 23-34. Heiskanen-Mäkelä, Sirkka. In Quest of Truth: Observations on the Development of Emily Dickinson’s Poetic Dialectic. Jyväskylä: Jyväskylän Yliopisto, 1970. Hirsch, E. D., Jr. Validity in Interpretation. New Haven and London: Yale UP, 1967. Homans, Margaret. Bearing the Word: Language and Female Experience in Nineteenth-Century Women’s Writing. Chicago and London: U Chicago P, 1986. Johnson, Greg. Emily Dickinson: Perception and the Poet´s Quest. University, Alabama: U of Alabama P, 1985. Juhasz, Suzanne. “Reading Doubly: Dickinson, Gender, and Multiple Meaning.” Approaches to Teaching Dickinson´s Poetry. Ed. R. R. Fast and C. M. Gordon. New York: Modern Language Association of America, 1989. Keller, Karl. The Only Kangaroo Among the Beauty: Emily Dickinson and America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1979. Kent, Beverley. Charles S. Peirce: Logic and the Classification of the Sciences. Kingston and Montreal: McGill-Queen’s UP, 1987. Lausberg, Heinrich. Elemente der literarischen Rhetorik. 8th ed. München: 22 Hueber, l984. Leyda, Jay. The Years and Hours of Emily Dickinson. 2 vols. New Haven and London: Yale UP, 1960. Lindberg-Seyersted, Brita. The Voice of the Poet: Aspects of Style in the Poetry of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard UP, 1968. Link, Franz H. “Emily Dickinson: Kunst als Sakrament.” Literaturwissenschaftliches Jahrbuch, 17 (1976): 129-189. Loeffelholz, Mary. Dickinson and the Boundaries of Feminist Theory. Urbana and Chicago: U of Illinois P, 1991. Lucas, Dolores Dyer. Emily Dickinson and Riddle. Dekalb, Ill.: Northern Illinois UP, 1969. Lynen, John F. “Three Uses of the Present: The Historian’s, the Critic’s and Emily Dickinson’s.” College English 28, no. 2 (November 1966): 126-36. Miller, Cristanne. Emily Dickinson: A Poet´s Grammar. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard UP, 1987. Monteiro, George and St. Armand, Barton Levi. The Experienced Emblem: A Study of the Poetry of Emily Dickinson. New York: Burt Franklin, 1981. Mossberg, Barbara A. Clarke. Emily Dickinson: When a Writer Is a Daughter. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1982. Ohnuki-Tierney, Emiko. “Embedding and Transforming Polytrope: The Monkey as Self in Japanese Culture.” Beyond Metaphor: The Theory of Tropes in Anthropology. Ed. James W. Fernandez. Stanford, California: Stanford UP, 1991. Patterson, Rebecca. The Riddle of Emily Dickinson. Boston, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin, 1951. Poe, Edgar Allan. “Eureka: An Essay on the Material and Spiritual Universe.” Selected Prose, Poetry and Eureka. Ed. W. H. Auden. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1950. Pollak, Vivian R. Dickinson: The Anxiety of Gender. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1984. Porter, David. Dickinson: The Modern Idiom. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard UP, 1981. Salska, Agnieszka. Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson: Poetry of the Central Consciousness. Philadelphia: U of Philadelphia P, 1985. St. Armand, Barton Levi. Emily Dickinson and Her Culture: The Soul´s Society. New York: Cambridge UP, 1984. Schwanitz, Dietrich. Systemtheorie und Literatur. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag, 1990. Sebeok, Thomas A. and Umiker-Sebeok, Jean. “You Know My Method.” In The Sign of Three: Dupin, Holmes, Peirce. Ed. Umberto Eco and Thomas A. Sebeok. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1983. Sewall, Richard B. The Life of Emily Dickinson. 2 vols. New York: Farrar, 23 Straus and Giroux, 1974. ---. The Lyman Letters: New Light on Emily Dickinson and Her Family. Amherst, Mass.: U of Massachusetts P, 1966. Shelley, Percy Bysshe. “A Defense of Poetry.” In The Selected Poetry and Prose of Shelley. Ed. Harold Bloom. New York and Toronto: The New American Library, 1966. Small, Judy. Emily Dickinson: Positive as Sound. Athens, Georgia: U of Georgia P, 1990. Smith, Martha, Nell. Rowing in Eden: Rereading Emily Dickinson. Austin: U of Texas P, 1992. Stonum, Gary Lee. The Dickinson Sublime. Madison, Wisconsin: The U of Wisconsin P, 1990. Weisbuch, Robert. Emily Dickinson’s Poetry. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1975. Wolff, Cynthia Griffin. Emily Dickinson: A Psychobiography. New York: Knopf, 1986. Yukman, Claudia. “Breaking the Eschatological Frame: Dickinson’s Narrative Acts.” Emily Dickinson Journal 1, no. 1 (1992): 76-94.