Teaching Technical Writing: Teaching Audience Analysis and

advertisement

)

Teaching Technical Writing:

Teaching Audience

Analysis and Adaptation

Edited by Paul V. Anderson

Anthology No. 1

J\

The Association of

,.,.,Teachers of Technical

L . . .ting

TEACHING TECHNICAL WRITING:

TEACHING AUDIENCE ANALYSIS AND ADAPTATION

Anthology No. 1

This anthology series was established to provide another service for

members of the Association of Teachers of Technical Writing. The

Association hopes that the series will encourage members to do

research and writing that reflects some of the major concerns of the

Association--foremost of which is the improvement of the teaching of

technical writing .

Anthology Series Editor:

Donald H. Cunningham, Morehead State University

Issue Editor:

Paul V. Anderson, Miami University

ATTW Officers:

President--John A. Walter, University of Texas

Vice-President--John H. Mitchell, University of Massachusetts

Secretary-Treasurer- -Nell Ann Pickett, Hinds Junior College

Editor--Donald H. Cunningham, Morehead State University

Copyright o 1980

Association of Teachers of Technical Writing

FOREWORD

Paul V. Anderson

Miami University

This anthology is intended to provide teachers of technical

writing with ideas and material for teaching audience analysis and

audience adaptation. Readers will learn various ways of teaching

their students how to increase the effectiveness of their writing by

first analyzing the important characteristics of their audiences and

second adapting to those audiences the contents, organizatiOJk~yle~

an~er features of their communi~tions .

Teachers who are new to technical writing wi ll find t he five

essays in this anthology very useful. Although these teachers may

have taught audience analysis and adaptation in other writing courses ,

such as freshman composition , they will discover that the two topics

are usually treated much more intensively in technical writing.

Experienced teachers of technical writing will also find this

anthology valuable because, in all the essays , the authors proceed

beyond the standard wisdom on their subjects to suggest new ways of

thinking about and teaching audience analysis and adaptation .

Thomas E. Pearsall opens the collection by offering a simple yet

elegant way of explaining to students ~they must tailor their

communications to the specific reader they are addressing . He also

supplies a worksheet that helps students focus their attention on the

information they must have about their reader if they are going to be

able to tailor their communications effectively . Like other

worksheets of this kind, Professor Pearsall's asks students to provide

information about the reader's background, such as the reader's job

title, educational level, and familiarity with the subject at hand .

It also asks students to do two other, very important things. First ,

it asks them to di,;tingui~ between their purpose in wrjti..ll9...a.llil.their

reader's ourpose in ' reading. a distinction that students too often

overlook. Second, the worksheet asks students to think about the

specific effects they intend their communications to have upon the

reader: what should the reader know after reading and what should he

or she be able to do then? Professor Pearsall is particularly helpful

when he explains the high degree of specificity that teachers should

require students to provide when describing the effects they intend

their communications to have.

In the next essay, Myron L. White joins Professor Pearsall in

urging teachers to teach students to look beyond such background

information as the reader's educational level when analyzing their

audiences . Professor White argues that students should also determine

what information the reader needs from the communication being

iii

iv

prepared. Using the example of a series of reports on a damaged

turbine in a power plant, Professor White shows how completely the

reader's info~ational needs degend UQQD the reader's reason for

readjog. ,Thus, the plant manager of the power plant would need one

kind of information in a report written when the turbine stopped

working, and an entirely different kind of information if the repairs

to the turbine fell behind schedule. At the conclusion of his essay,

Professor White tells how to design assignments that require students

to analyze the jnformation~l nee~s qf their reader and then use what

tbev have learned to determine the contents of their comm~ications.

Merrill D. Whitburn broadens the discussion by reminding us that

teachers have developed three distinct type~technical wri!ing

courses, each designed for a particular kind of student: students

majoring in such disciplines as accounting and engineering who want to

learn how to do the writing that accountants and engineers do on the

job; students majoring in any discipline who want to become

professional communicators; and students preparing to become teachers

of technical writing. Professor Whitburn describes several techniques

for teachin9 audience analysis and adaptation that are appropriate in

courses for all three kinds of students. For example, he tells how

teachers can serve as models for students to emulate--by learning

about the students in the classroom (the teachers ' audience) and then

adapting their courses to those individuals. In addition, Professor

Whitburn offers some very interesting suggestions for teaching

audience analysis and adaptation that would be suitable for only one

or two of the three kinds of students.

David l. Carson begins his essay by pointing out that for the

writer, the reader is always fictive. Even when describing a reader

he or she knows personally, the writer is creating an artificial

mental image of the reader. The writer's task is to make that fictive

description as realistic as possible . As Professor Carson explains,

this realism can be especially difficult to achieve when the writer is

addressing a reader the writer cannot observe directly. Professor

Carson then proposes one possible method for overcoming this

difficulty . While the details of his plan will be particularly

interesting to those who are teaching students to become professional

technical communicators, Professor Carson's description of the problem

and his general strategy for solving it can enrich any technical

writing teacher's ability to discuss with students the aims and

techniques of audience analysis.

Michael L. Keene and Merrill D. Whitburn round· out this anthology

with a selected, annotated bibliography. This bibliography is

especially valuable because of the wide range of material the authors

discuss. They include the little-known along with the widely read,

the theoretical along with the practical, and useful items from other

disciplines along with items that focus specifically on technical

writing. Thus, their essay serves not only as a starting point for

v

further study, but also as a portrait (thanks to their informative

annotations) of the wide range of materials that can be drawn upon for

use in the classroom--and as a basis for research.

It is, of course, impossible to guess the directions to be taken

in coming years by the people who will be developing new pedagogical

techniques and conducting research in audience analysis and

adaptation. Nevertheless, two trends appear to be emerging. First,

there seems to be a trend toward advising students (and other writers)

to learn about their reader in greater detail than was thought

necessary in the past. Evidence of this trend appears in each of the

first four essays: in Professor Pearsall 's insistence that students be

very specific when describing what they intend the reader to know and

to be able to do after reading; in Professor White's suggestion that

students determine very precisely what the reader's informational

needs are; in Professor Whitburn's differentiation among the kinds of

students enrolled in technical writing courses; and in Professor

Carson's suggestions for achieving greater realism in the fictive

portrait that students create of their reader. The second trend is an

increasing desire to discover what other disciplines can teach

technical writing about audience analysis and adaptation. Evidence of

this trend can be found in the range of material included by

Professors Keene and Whitburn in their bibliographic essay, as well as

in the breadth of the material drawn upon by the authors whose work

they cite. If this trend continues, technical writing teachers (and

technical writers) may soon find themselves asking what they can learn

about audience analysis and adaptation by reading the literature and

using the research techniques of cognitive psychology, sociology, and

other disciplines that previously had seemed unrelated to technical

writing.

Whatever trends develop in the coming years, the essays in this

anthology will remain a good starting point for teachers wish ing to

learn how to teach audience analysis and audience adaptation in

technical writing courses .

*

*

*

For help they gave me during the preparation of this anthology, I

wish to thank the authors of the five essays, as well as Professors

Donald H. Cunningham, Mary Sohngen, James W. Souther, Dwight W.

Stevenson, and C. Gilbert Storms. In addition, I am very grateful to

Pamela Harris and Deb Schoenberg , who helped prepare the final copy.

The first four essays were originally written for a special session

sponsored by the Association of Teachers of Technical Writing at the

1977 convention of the Modern Language Association. Professors Keene

and Whitburn prepared their bibliographic essay expressly for this

anthology.

•

C0 NT ENT S

THE COMMUNICATION TRIANGLE

Thomas E. Pearsall

1

THE INFORMATIONAL REQUIREMENTS OF AUDIENCES

Myron L. White

6

AUDIENCE: A FOUNDATION FOR TECHNICAL WRITING COURSES

Merrill D. Whitburn

18

AUDIENCE IN TECHNICAL WRITING: THE NEED FOR GREATER REALISM

IN IDENTIFYING THE FICTIVE READER

David l. Carson

24

AUDIENCE ANALYSIS FOR TECHNICAL WRITING: A SELECTIVE,

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Michael L. Keene and Merrill D. Whitburn

32

vii

THE COMMUNICATION TRIANGLE*

Thomas E. Pearsall

University of Minnesota

A piece of tecb.Jlica.l or occl.WationaL.wt:Lttng_does_not_c.QJDe

into bejng unless there is an occasion for jt. The occasion

includes the message to be transmitted, the receiver of the

message, and the purpose of the transmission. Technical and other

occupational writing is usually generated by a specific piece of

information that has to be transmitted: Your bicycle has been

repaired; please come pick it up •••• The HRW-14 computer is

superior to the BBF-198 •••• We attended the convention in

Seattle •••• This is how vou build the 86204 Heat Exchanger.

Occupational writing is not generated for the joy of personal

expression, though the writer may enjoy doing it. In the world of

work, people write when they have something to say.

When a writer prepares to send a message, he must think of

his audience. Messages are not merely sent; they are sent to

someone. The writer must always be concerned with these

questions: "Who wi 11 read my report?" "Why wi 11 they read it?"

"What will they want from it?" "What do they already know about

the subject?" "What is 1eft to te 11 them?" Writers of sa 1es

letters try to fix in their minds the typical buyer of the product

being sold. A person writing a letter of application should know

something about the employer. How else can he emphasize the

skills the employer needs?

Suppose an inventor has designed a new product--a heat

exchanger for getting more heat from an open fireplace into the

house. He would explain the heat exchanger one way to the bankers

from whom he hopes to borrow the money needed to manufacture the

product. They need to know only enough technical details to be

sure the product will work. Mostly, bankers will want convincing

evidence that there is a market for the product. The inventor

would explain the heat exchanger another way to the people who

will manufacture it for him. They need step-by-step instructions

about the manufacturing process. He will explain the heat

exchanger still another way to the people to whom he intends to

*Portions of this paper first appeared in Thomas E. Pearsall

and Donald H. Cunningham, How to Write for the World of Work

(New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1978).

1

2

sell it. They \vill want to know what the heat exchanger will do

for them in their homes. How much, for example, could it save

them in fuel bills?

As you have perhaps noticed, purpose is usually closely

meshed with the audience chosen to receive the message. The

inventor writes a certain way for bankers so that the bankers can

get the information they need. But he went to the bankers in the

first place because his purpose was to get a loan.

It is not always quite that simple. Sometimes writers don't

recognize the multiple purposes that should govern their work.

Suppose, for example, a writer is sending someone bad news,

perhaps that his automobile insurance rates are going up. If the

writer's purpose were only to announce the new rates, he could

send out a printed table showing the increase. But he will have

another purpose as well. His additional purpose will include

keeping the policyholder with the company. To do this, he must

maintain goodwill. Therefore, he must do more than merely

announce the rate hike. He will have to justify the hike--to show

how conditions beyond his company's control have forced it. He

would probably take the time to mention the good service his

company has given in the past and intends to give in the future.

None of this justification and explanation would be necessary if

the \>Jriter' s purpose were only to announce the rate hike •

.

Message •••• audience •••• purpose •••• the basic triangle of

technical and uccupational writing.

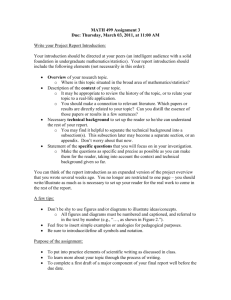

I have found the worksheet reproduced as Figure 1 an

effective device for helping students sort out message, audience,

and purpose. It brings home the message that we are never merely

writing; we are writing for someone. The worksheet leads the

student to answer questions such as those that follow.

What is the reader's educational level? If it's eighth

grade, for example, sentence structures had better be fairly

simple, about Reader's Digest length and style. Information

should be personalized through example and anecdote. If the

reader is college educated, perhaps Scientific American is the

model. If the reader has the necessary technical background to

understand the subject, the student need not supply it.

3

REPORT WORKSHEET

(Fill in completely and attach as cover sheet)

llriter:

For

Primary Grade - - - - instructor Mechanics

use only

Final Grade

Subject:

Reader

(person assumed to actually use information presented)

Technical level (education, existing knowledge of subject, experience,

etc.) :

Job title and/or relationship to writer:

Attitude toward subject (interested, not interested, hostile, etc.):

Other factors:

Reader's Purpose(s)

\1/hy will the reader read the paper?

~hat

should the reader know after reading?

1\'hat should the reader be able to do after reading?

l~riter's

PUl'pose(s)

Primary purposc(s):

Secondary purposc(s):.

Content and Plan

:SOurce-mat~rials (direct study, library research, personal knowledge,

etc) :

Primary organizational plan (exemplification , definition, classification,

causal analysis, process description, narration, argument, etc.):

~.fedium

prescribed or desirable (mass mediun, 1 imi ted medium, company

report, memorandum, correspondence, etc.):

Available aids (visuals, tables, etc.):

Figure 1.

Report Works heet.

4

What is the reader's attitude toward the subject? Knowing

this can govern much of what the student does. Not every report

needs an attention-getting introduction--only those for

uninterested people do. Is the reader an executive and someone

likely to be receptive to the report's conclusions and

recommendations? Then the student knows he should give the

conclusions and recommendations first. If the reader is likely to

be hostile, the student holds his conclusions for last.

In the section on reader's purpose, I urge the students to be

quite specific. The

following would be an unsatisfactory answer

for the question, 11 What shou 1d the reader know after reading? ..

The reader should understand about stress and distress.

The following answer is excellent:

The reader should be able to {1) define good mental

health; {2) recognize the clues that let us know our

minds and bodies are becoming distressed; {3) use

problem-solving techniques to release stress; and

(4) identify the sources of expert help available

in case this is needed.

The writer of the first objective demonstrated no clear idea

of where he was heading. The second writer not only demonstrated

his objectives but probably organized his paper as well.

The student should be equally specific about what the reader

should be able to do and about his purposes. A common experience

for me before I began using this worksheet was to have students

supply far more information than their purposes called for or the

wrong information. A student might , for example, be trying to

persuade someone that controlled burning in our forests is a

feasible process that promotes a healthier forest. But in his

paper he would de~cribe the process at a level suitable for a

technician who actually had to control the burning--material that

is both more and less than that needed for the student's purpose.

Using the worksheet, he is more likely to recognize that what is

really needed is an argument that demonstrates the salutary effect

of controlled burning on forest growth and wildlife and that also

demonstrates the process to be economical and environmentally

safe.

This section also helps the student to recognize the

secondary pur~oses th~t may exist--such as maintaining the

goodwill of t __e reader.

The Content and Plan section concerns standard material dealt

with in most composition classes, but now it is seen in the light

5

of the audience and purpose analysis that has been done. For

example~demonstraJJLOR feasibility is the major purpose of the

paper. an analytical organization is called for, such as

classification, causal analysis, or argumenr:--PrOcess descrrption

would be the wrong approach.

Considering the medium suggests the flexibility available to

the student. It lifts the assignment out of the usual student

report category. It suggests that perhaps for certain purposes a

newspaper article is the best approach. In other situations an ad

or a direct mail letter might be what is needed. These are

considerations that bring the world of work into the classroom.

For far too long, the student has had an audience of one--the

teacher. The purpose has been to get a good grade. Considering

the communication triangle gives the student a new outlook and a

more realistic set of objectives. Teachers for their part gain a

new set of criteria upon which to grade--criteri a much closer to

those the student will face when he leaves the classroom.

THE INFORMATIONAL REQUIREMENTS OF AUDIENCES*

Myron L. White

University of Washington

Perhaps I can get most quickly to my subject by repeating two

points which Cleanth Brooks and Robert Penn Warren make in their

book Modern Rhetoric. In discussing the problem of adjusting tone

to different audiences, they say, "Writing which demands that the

author take into account his particular audience is •• • always

'practiGal • writing--writing designed to effect some definite

thing."l Then they go on to advise, "If such writing is to be

effective, the author must, of course, keep his audience

constantly in mind."2

Now, for my present purpose, Brooks and Warren's first

statement characterizes technical writing very well. Technical

writing is "practical" writing; it always has a definite purpose

and goes to a particular audience, which the writer must take into

account. Consequently, the admonition to keep the "audience

constantly in mind" is one of the best pieces of advice which

teachers of technical writing can offer to and demonstrate for

their students.

But just what does it mean to keep an audience in mind? I

ask the question because in so many textbooks the discussions of

audience seem unfortunately limited in scope. Usually they

emphasize how audiences can differ in matters of age, interest,

prejudice, amount and kind of education, experience, familiarity

with a subject, and so on. In other words, the stress lies on the

variations in background which different audiences may bring to a

given subject matter. Then, as a consequence of this stress,

writers are advised on little more than how to adjust their

language so that they can meet the expectations of a particular

audience. What so often is missing, of course, is discussion of

how particular, or special, audiences can affect the conteQ!_£!___

J!ritins, as well as it~ ~pression. To be sure, some texts do

mention that reaching one type of reader, rather than another, can

require adjustments of content. Moreover, a smaller number of

texts push this idea somewhat further, noting, for example, that a

*Parts of this paper first appeared in James W. Souther

and Myron L. White, Technical Report Writing, 2nd ed. (New

York: John Wiley &Sons, 1977).

6

7

lay audience will require more background on a speciali zed subject

than will an audience of experts. Seldom, however, is it possible

to find discussions of audience which recognize that each special

audience can, and usually does, have its own very real demands for

specific kinds of information.

The point is that most efforts to instruct writers about what

to do for their audiences simply do not go far enough . In

technical writing, at least, audiences differ not only in their

backgrounds but also in their needs for information, or what I

have called their informational requirements. Thus, for technical

writers. keeojng an audim in mind includes two major concerns:~ting a content which will meet its informational requirement~

aru1-choosing_language to suit its background.

WHAT INFORMATIONAL REQUIREMENTS ARE

What these informational requirements can mean in practice

becomes clear if we watch technical writers at work . Actually,

most of the writing which scientists, engineers, and other

professionals do in industry and government results from specific

assignments. The assignment may be a direct one, as when a

supervisor in a hydroelectric plant says, 11The boss wants a report

on Turbine No. 2 by day after tomorrow. 11 Or the assignment may be

clearly implicit in the way an organization normally conducts its

activities. For example, a research team attempting to develop an

electrical array for guiding fish in a stream seldom has to be

told that eventually it must produce one or more reports on its

work.

At first glance, it may appear that in either case the

writers have little choice of subject matter. Whoever gets the

assignment must report on the grave condition of Turbine 2 (if it

is grave), even though he or she would prefer this week to

describe the principles for designing the perfect turbine. And,

at report writing time, members of the research team must set

aside their schemes for breeding the ideal fish and inform the

Director of Research about what they have done and what they

believe they have accomplished by doing it. Yet appearances can

be deceiving. There is, surprisingly enough, a great deal to be

said about a turbine or about shocking fish into the right path.

Consequently, our imaginary writers, as do real ones, face a

serious question of what to write about.

Many technical writers, unfortunately, take care of the

question by ignoring it, reporting as much about turbines or

shocked fish as their knowledge, time, and patience will permit.

They do so because, in part, they are insufficiently aware that

they are writing to special audiences. They do not realize or pay

8

too little attention to the fact that managers of hydroelectric

plants and research directors do not ask for or expect reports

because of a deep personal desire to learn all there is to know

about electricity, fish, or turbines~ ~at these audiences do

want most often is the io.formation they reqjJi..r._eJor making

decisions themselves or for recommending_decisio~~_ta snmeac~

else.

Recognizing that managers want information for decision-making

should prove helpful to the engineer who must write the report on

Turbine 2. Nevertheless, such understanding is not likely to be a

sufficient guide in selecting the content which the report should

contain. Understanding the immediate situation is also important.

Why did the plant manager ask for this report? In reality, of

course, the answers to this question will differ as widely as the

situations which give rise to it. So let us suppose, for example,

that, because it had been damaged, our troublesome turbine was

shut down yesterday and that the period of highest demand for

electrical energy is just beginning.

Under these circumstances, it becomes reasonably clear that

the plant manager must make decisions about ordering parts and

materials, recalling personnel from vacation, requiring overtime,

and requesting expert help either from outside the plant or from

outside the utility company which owns it. In order to make these

decisions, the manager requires information about what kind and

amount of damage the turbine sustained, who and what are required

to repair it, and whether or not the plant has the people and

other resources available in order to carry out the repair.

Equally pressing will be other decisions about the need for

budgetary transfers and the problem of meeting an increasing

demand for electricity. For these also, the engineer must prepare

the manager by providing realistic estimates of cost and time for

the repair.

Naturally, w~ could have supposed a number of other possible

situations. Because repair of the turbine was behind the

estimated schedule, for example, the manager could have wanted to

learn what difficulties were being encountered in order to decide

what, if anything, should be done about them. Or, with the

emergency taken care of, the manager could have wanted to

determine if there were an economical way to prevent such damage

in the future. The list of occasions requiring a report on

Turbine 2 could go on. However, three examples probably are

enough to make the point: the informational requirements of a

special audience (in this case, the manager of the hydroelectric

plant) can differ each time the audience asks for a report.

Hence, selectin_g_t~ ap_Qropriate content of each report deQends_

very greatly on why the audience asked for it in the first place.

9

At the same time, these observations generally hold true for

a research director who may seldom ask for reports, but expects to

receive them anyway. It may be customary in a research

organization, for example, that, when a major project reaches a

certain stage, the director must get a progress report so that he

or she can determine the advisability of continuing the project.

Facing this situation, the research team attempting to guide fish

by means of electrical impulses not only must describe what it has

done but also must provide careful answers to such questions as

the following: Does the original concept still appear to be

feasible? What problems has the team encountered? Can it solve

them? How much more time and money will be necessary to conclude

the project successfully? Are the potential benefits worth the

time and money required?

On the other hand, let us suppose that the team has

successfully guided fish with a system which it has devised and

the director is waiting for the final report on the project. Once

again, the informational requirements of the audience have

changed, for the decision to be made has shifted from whether the

project should continue to what should be done with the final

result.

Ordinarily, the latter decision is one which research

directors do not make, but they must have enough information on

the system, its operation, its safety, its reliability, its

probable costs, its advantages, and its disadvantages to guide the

decision-making of others. In any case, the absence of a direct

assignment should not tempt the technical writer into overlooking

the informational requirements which a special audience can have

on each occasion it expects a report.

At this point, I trust that my handful of examples has made

reasonably clear what I mean by informational requirements and how

important they are in technical writing. I must grant that the

examples come fro.~ a limited area of the field--reports, written

to a relatively well -defined type of audience, managers, who are

known to make all kinds of decisions. Yet close observation will

show that fulfilling the informational requirements of each

special audience is equally important in preparing effective

instructions to operators of equipment, repair and maintenance

manuals for the technicians who must keep the equipment running,

sales brochures for potential customers, and proposals to funding

agencies--to cite just a few of the different writing tasks which

scientists and engineers may face.

10

WHY WRITERS AT WORK DON'T LEARN

It can be argued, of course, that technical writers must

learn the nature of their audiences' informational requirements on

the job. And, to a degree, this point is a valid one.

Unfortunately, the occasions when they do learn enough about their

audiences represent the exception, not the rule, in their work.

There are two major causes of this circumstance. The first is the

supervisors and managers who assign writing (and, at the same

time, complain about the poor writing of the engineers and

scientists who work for them). The second cause is inadequate

writing instruction at school, which leaves the graduating

scientist or engineer unprepared to distinguish one real audience

from another.

(~)

Poor Guidance on the Job

So far as managers are concerned, either they are

unacquainted with the idea of writing for special audiences or,

having learned themselves to write effectively for such audiences,

they assume that everyone else knows as much as they do. As a

result, they usually ask for reports in an offhand manner, with

little, or no, recognition that one occasion for writing differs

from another. And those who, by the rules of the game, expect

reports on given occasions seldom talk about what they

expect--until they must review and approve a completed report with

which they are displeased. Then, of course, the atmosphere of

confrontation between manager and writer does not encourage anyone

to teach or learn anything about audiences .

Very often, also, the origins of writing assignments (and,

hence, the readers) are at some level above the writer in an

organization's managerial structure. By the time that information

about an assignment has descended through the "chain of command"

to the writer, it is highly abbreviated and even garbled.

Moreover, the technical writer's message must travel upward to its

audience by the same route which the assignment took in coming

down. As it does so, it runs an obstacle cpurse. Each manager

standing between the writer and the true audience assumes that he

or she is that audience and asks for revisions of the message with

too little regard for its final destination. The result of all

this message handling is not just that writers learn very little

about what their readers have asked for or expect but also that

they become confused about who their true readers actually are.

In effect, then, technical writers can be screened off from

audiences within their own organizations because the persons

transmitting the assignments are not the ones who truly need to

learn something from what they write. This handicap can become

11

even greater when those assigning writing tasks are not the true

audience or among its members--that is, when the report, document,

or whatever it may be is directed to an audience outside the

organization. On these occasions, the screen may not be a

kaleidoscope of partial and conflicting information; it may simply

be blank. Management itself may know nothing of consequence about

an audience which it is trying to reach, or, if it does, the idea

of providing writers with this kind of information may never occur

to anyone, may be overlooked, or may be considered unimportant.

Furthermore, when the knowledge of an audience is inadequate, too

few managers make the effort to increase it. Nor do they

encourage writers to learn enough about an audience so that

reasonable assumptions, at least, can be made about its background

and its 11 informational requirements. The result is 11 TO Whom It May

Concern writing which may satisfy everyone involved, except the

readers. And surely all of us have experienced how this kind of

writing fails to serve a special audience. At one time or

another, haven't we all exhausted our four-letter-word

vocabularies on the instructions included with a knocked-down toy

or piece of furniture which we had to put together?

Poor Preparation in School

No doubt, while we were damning the writer, we did not

overlook the manager or managers who approved a set of

instructions fit only for mind readers. But it is unfair to hold

that managers are entirely responsible for the failure of

scientists and engineers to learn about their special audiences on

the job. To take this view, we must assume that technical writers

are prepared to learn about these audiences in the first place,

that they understand what a special audience is and what to do

about it. The fact is that too many of them are ill prepared to

distinguish among audiences, to determine what each one may need

at a given time, and to write accordingly.

Too often, young technical writers can treat communication as

if it were simply a matter of writing their messages down on paper

and delivering them to someone else--presumably anyone will do.

What happens after that is someone else's problem, or so they

believe until they have had to revise several reports drastically

in as many different ways. At this point, they can become

defensive, even cynical, about learning to play a game which

apparently has no rules. In some organizations, of course, their

view of the matter can be an accurate one, but technical writers

also can have too simple and rigid a view of how to write

effectively. They can fail to understand that, as someone has

said, communication only begins when the message truly reaches _i~t~s_______

reader. Or, if they do accept the idea of carefully identifying

12

each audience and keeping its special requirements in mind, they

can have difficulty with putting this advice into practice.

HOW WRITING TEACHERS CAN HELP

Whatever may happen to technical writers on the job, teachers

of technical writing should prepare their students as well as they

can to communicate effectively with a variety of audiences in many

different situations. Doing so does not mean briefly introducing

the concept of audience and citing an example or two of its

importance to effective writing. It means developing implications

of the concept in detail, illustrating these with concrete

examples~ and demonstrating how specific audiences should affect

whatever the scientist or engineer writes.

What to Teach

Opinions can differ, of course, about what aspects of

audience are most important for students to learn. My own

prescription includes the following.

First, students should become well acquainted with the

general types of audiences for which they are likely to write as

professionals. At a minimum, the types should include fellow

experts, executives (or managers), technicians, operators of

equipment, and laymen.3 In learning about these audiences, the

student should become familiar not only with their general nature

and probable backgrounds but also with the reasons which they

usually have for reading what an engineer or scientist may write.

In other words, what are the basic kinds of information which an

audience of experts, managers, or technicians usually requires?

Second, it also is important to extend one step further the

student's under~tanding of the general audience types. On the

job, technical writers do not face types of audiences. They write

to particular individuals or groups which may be of one type or

another. Moreover, on a given occasion, each of these particular

audiences probably will have very specific informational

requirements. Normally, such requirements fall within the basic

kinds of information which operators, for example, usually need,

and frequently a writer can deduce from a situation and a general

knowledge of operators what it is that a group of them requires.

Certainly, when writers are screened off from a special audience,

they may be able to make reasonable assumptions about i t if they

know into what type it seems to fit and, thus, what information it

is likely to need or want. On the other hand, guessing at the

nature of a particular audience, and especially its informational

requirements, is never as good as knowing. Consequently, before

13

technical writers fall back on generalizations about audience

types, they should attempt to discover as much as they can about

each special audience and its needs . The more accurate the

knowledge about an audience which writers have, the more clearly

they can identify and define it, and, hence, the more readily they

can keep it in mind.4

Third!.. students should learn the importance, and acq_yire the_

habit, of defining as well as they can the nature and needs of a

jhar~icular audience at the beginning of each wr1ting a~men~

They should recognize that only this definition can provide a

reasonable basis for decisions which they must make throughout the

writing process. The answers to questions about the background of

the audience, for example--what is its education? what is its

general experience? what is its experience with the company? and

so on--help to guide the gathering, evaluating, and selecting of

content for a piece of writing. They aid writers in determining

how much background on a subject, how much in the way of

mathematical concepts, and how many other technical details are

appropriate for a particular audience. And they become very

important at the time of writing a first draft and revising it,

for they affect the manner of presenting content in many ways,

ranging from choice of vocabulary to the design of illustrations.

Finally, students must realize that the answers to questions

about a particular audience ' s informational requirements are basic

to determining the content of what they write. About these

requirements, technical writers should seek clear answers to at

least three questions. ILthey have received a direct assi.wlme.nt,

they should be sure that they fully understand what the audience

has asked tor. Conside~afion of tnis question should not be taken

-rightly. Managers who make or transmit assignments are not always

clear in doing so. On the other hand, writers can receive

assignments carelessly and have an incomplete and hazy

understanding of them. Incidentally, if the assignments are not

direct ones, the question of what the audience asked for can be

translated into what does the audience want. In either case, if

writers are in any doubt about the essential information which an

audience needs, they should not hesitate to ask for or otherwise

seek clarification.

Once they are clear about what an audience has asked for or

wants, writers should consider the answer to another question:

what additional information should they provide so that the

audience can fully understand or make use of the essential

information it needs? Answers to this question can take many

forms, but perhaps a simple example will suggest its significance

for technical writers. A manager has asked for information about

three pieces of equipment in order to decide which one should be

purchased. Knowing what the manager expects, the scientist

14

responding with a report has recognized that comparative data on

performance and cost are essential content. After some thought,

however, the writer also concludes that, although the manager did

not ask for them, the requirements which the equipment must

satisfy should also be in the report. They also are important to

making a decision.

Conveniently enough, this last example introduces the third

question which writers should raise about the informational

requirements of an audience. Will what they write provide the

basis for decisions, and, if it will, what kinds of decisions?

Very often, the kinds of information which scientists and

engineers possess do get used to support a variety of decisions

made by a variety of audiences. Managers are only the most

prominent among them. In any case, how sound these decisions are

may well depend upon whether or not technical writers provide

enough of the right kind of information in a manner that is

accessible and understandable to their readers. Consequently,

they should consciously raise and answer the the third question

whenever they write.

How to Teach It

Perhaps my prescription of what a technical writing course

should include about audiences seems overly full of ingredients.

However, I b~ljev~ th_a_t the teacher•s_g_oal should be to make the

technical writer so conscious of readers that writing for them _

becomes almost second nature. Furthermore, attempting to achieve

tnTs goal means that teachers should avoid organizing courses so

that the matter of audience becomes a separate segment, largely

set off from what comes before and after. Concern for readers

should pervade a course from beginning to end . It should be

present explicitly in discussions of selecting content, organizing

it, handling graphic illustrations, choosing report or other

forms, drafting o ~d revising content, and seeking appropriate

styles and ton~s. It also should be present in every, or almost

every, writing assignment of the course.

And throughout, the teacb~r should put a significant stre~s

£nLthe informational requirements of audiences._ It is very

helpful, naturally, if the course•s text takes up these

requirements in some detail. Indeed, teachers of technical

writin_g could very well include an adeg_uate handling of audience

needs among the criteria which they use in selecting their textbooks. "Yet, even without such help, the teacher can gTVe

informatio-nal requirements adequate attention by means of class

handouts, lecture, and class discussion. This third teaching

device, incidentally, is rather important. For many students, the

idea of writing to particular audiences, let alone taking care of

15

their special informational requirements, can be an unheard of

notion which complicates unnecessarily the writing activity.

Liberal amounts of classroom discussion, however, permit students

to air their objections to the idea, to pursue its implications

for themselves, and gradually to become accustomed to it.

Whatever they do, teachers should ensure t_hat no discussion of

audience remains at_a hi~Y- abstract lev~ Handouts, lectures,

and class discussions should contain or focus on concrete examples

of particular audiences having specific needs which must be met in

specific ways. Coming up with such examples is not so difficult

as it may sound. It would be a highly unusual teacher who had

never faced practical" writing situations in his or her career.

11

But talk about audiences and their informational requirements

is not enough. Students need to work with the ideas they have

read or heard about special audiences. In order that they may do

so the exercises and writing assignments of a course in technical

writing should simulate the actual kinds of situations in which

engineers and scientists must write. In other words, each

assignment should be set within a particular context which

establishes a special audience for the students to define and keep

in mind. The information provided for such a context should be

sufficient so that they can learn directly or can infer the

answers to such questions as what the audience has asked for or

what it wants, what additional information it needs, and what

decisions, if any, the audience will be making. At the same time,

students should be made to realize that how well they succeed in

meeting an assignment will depend upon how well they answer these

questions and then follow through by fulfilling their audience•s

informational requirements in what they write.

~s_ome_assi

gnments, teachers c.ao...provjde the. fulLcontex.t_

can provide a class, for example, with a set of

data on the comparative performance and costs of two or three

pieces of equipment, describe the circumstances under which the

equipment will be used, and then ask the students to report on

this equipment to the manager of an office (or a manufacturing

plant or whatever) so that the latter can intelligently decide on

which piece of equipment to buy. Putting together assignments of

this sort takes some ingenuity and labor, naturally, and not all

effective assignments need be so demanding on the teacher.

the~~elves ..... They

Others, in fact, offer the advantage of having the student

define the requirements of an audience largely from his or her own

knowledge . One of these is to write a set of instructions on how

to assemble, operate, disassemble, or repair a relatively simple

piece of equipment, or on how to perform any operation with which

students are familiar. The choice of subject can be theirs, and

about audience the teacher need only require that it be one which

knows as little as the students did before they learned how to

16

prepare slides for a microscope, adjust a carburetor, or bake

bread. Students usually are able to identify with such an

audience and to determine rather well what it wants and needs to

know. Incidentally, this assignment has an additional advantage

in the fact that the teacher usually qualifies exceptionally well

as the inexpert audience. Hence, evaluation of the assignment not

only is relatively easy (if I can't understand how to do it, then

the instructions are faulty) but also leads to the acquisition of

many fascinating, if not always personally useful, bits of

knowledge (ranging all the way, in my own case, from how to repair

pieces of diving equipment to a method of cutting out and

assembling hand puppets from scraps of cloth). 0

The two examples which I have just cited obviously do not

exhaust the possibilities for "practical" assignments in a

technical writing course. The important point, however, is that

the assignments be "practical." What students do in a course is

as vital to their learning about the informational requirements of

special audiences as what a textbook or teacher says. Indeed,

both aspects of teaching students about readers' needs deserve

careful attention.

As I suggested at the start, satisfying the informational

requirements of their readers is critical to the success of

technical writers. Unfortunately, they get too little help with

this problem on the job; .,oreover, too few are now well enough

prepared to learn much there anyway. On the other hand, the

latter deficiency need not be a fault of tomorrow's technical

writers. Today's teachers of technical writing can do much, if

they will, to see that it is not.

17

FOOTNOTES

1.

Cleanth Brooks and Robert Penn Warren, Modern Rhetoric (New

York: Harcourt Brace and Company, 1949}, p. 476.

2.

Brooks and Warren, p. 476.

3.

The classifications come from Thomas E. Pearsall, Audience

Anal}sis for Technical Writing (Beverly Hills: Glencoe Press,

1969 •

4.

11

0oing research on 11 and writing to an audience can become

especially complicated when it includes persons who fit into

different audience types (a combination of experts and

managers is frequent). In this case, technical writers should

determine which part of the audience is primary and aim at it,

making some special provisions for the secondary readers as

best they can.

5.

For further discussion of the kinds of writing assignments

suggested here, see James W. Souther, Developing Assignments

for Scientific and Technical Writing,,. Journal of Technical

Writing and Communication, 7 (1977), 261-269.

11

AUDIENCE: A FOUNDATION FOR TECHNICAL WRITING COURSES

Merrill D. Whitburn

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

For several years, I worked as a communication specialist in

Western Electric, the Gelman Instrument Company, and other

organizations. Again and again I would go to engineers about

quality control experiments or purchasers about cost reduction

cases only to find them utterly incapable of providing the

information I needed. They were unable to simplify their

vocabulary or concepts so that I could comprehend them; they

lacked a knowledge of other techniques of audience adaptation that

facilitate understanding; they chose not to simplify because they

wanted to impress rather than inform; or they seemed incapable of

selecting from their knowledge of a subject what was relevant to

my needs. I gradually came to realize that a key chdracterist~

t~ distinguished admjnistrators from_s~Qedinates was this v~y

ability to adapt to different audien~ The engineer who could

adapt his information about a product innovation so that an

Executive Committee was persuaded to support him would invariably

be considered favorably for promotion. When I left industry to

come to the university--a rmed with the conviction thatjiudie~

qdaptation was the mo~t serious communication problem faced by

employer~ -~ was delighted to see audience awareness being

emphasized by a number of teachers and scholars, perhaps most

notably, Tom Pearsall .

In this paper, I will suggest some ways of making audience

adaptation the very foundation of technical writing courses. I

speak of technical writing courses--in the plural --because a

number of universities are developing courses for three different

groups of students:

1.

The first group includes students majoring in

such disciplines as engineering and accounting

who intend to work in these fields . As professionals,

they will face such communication tasks--both

written and oral--as proposals and progress reports.

2.

The second group includes students majoring in

any field who intend to become full-time

professional communicators.

Such communicators

might edit annual reports, manuals, and brochures

or write slide talks, news articles, and product

stories.

18

19

3.

The third group includes graduate students

intending to teach technical communication at

colleges and universities. In addition to

teaching, they will be developing courses,

making contacts outside their schools, and

conducting research in the field.

Although each group must address the problem of audience

adaptation in its own special way, several techniques of

emphasizing audience adaptation are appropriate in courses for any

of the three. For example, eSfb teacher can serve as a model__by

adaptin~his teaching to the SRecific students in his classroo=

m~

· ---­

In order to do so, he must discover as much about them as he can.

Three of the most common ways of obtaining this information are

the letter of introduction, the letter of application and resume,

and conferences. If _audience awaren~ is to be the foundation

for courses, the concept ~ould be iDtroduced on the very first

rlay of class, the most prominent time in the entire semester. meconcept can be clarified through use of examples, and the students

can be motivated through stories of inadequate audience adaptation

in industry. When the students have grasped the concept, the

teacher might remind them that they are his audience and that he

must adapt to them. He might assign a letter of introduction to

teach one acceptable form of the business letter, and, more

importantly, obtain samples of their writing and information about

their backgrounds in communication, areas of specialization,

employment plans, and attitudes toward the course. When this

letter is handed in a few days later, the teacher might assign the

letter of application and resume. Invariably, his knowledge of

each student is strengthened through both repetition and

information that did not surface in the letter of introduction.

As the semester progresses, the teacher might hold two conferences

with each student to discuss the student's progress and explore

individual needs or changes in attitude.

All thi s information is without value, however, unless the

teacher uses it in actually adapting the course--within the limits

of course goals--to the individuals in the classroom. The teacher

might approve the subject for each paper after the letters, and he

should try to assist the students in choosing subjects that--given

their backgrounds and goals--will prove interesting, motivating,

and useful. He might devote special attention to those writing

problems that appear most frequently in the students' papers, and

he might use examples of good and bad writing from these papers as

a basis for class discussion. At a student's request he might

sometimes furnish information that he would not normally include

in the course. By showing his concern for individual students as

an audience, then, he would encourage them to concern themselves

with their audiences.

20

Technic~l writing_~ourses,

like

~t~er cours~~~n composi~n.

~be or~an1zed acco~d1ng to the three rhetorical_~tegorie~of

invention~ organization, and style~ In courses for all three

groups of students, a fruitful means of approaching these

categories is to explore the impact of audience on each. For

instance, with regard to invention, an audience of stockholders

might well require considerably more background information to

understand an experiment than a group of chemists. As another

example, the organization of a paper designed for an audience

interested in the functioning of an automobile will differ from an

organization designed for a group interested in the assembly

process. Finally, the style of a paper intended for engineers

might contain many more technical terms than the same materials

written for public relations specialists. Many similar examples

can be explored in class, and each assigned paper can be used as a

basis for generating more. Assignments should specify audiences,

and an important part of the evaluation process can be an analysis

of the extent to which the writer has made the appropriate choices

in content, organization , and style for the intended audience.

Other techniques of emphasizing audience adaptation may be

appropriate for only one or two of the three groups of students in

technical writing. In courses for students hoping to become

professionals in fields like engineering or accounting, the very

make-up of the class is critical to promoting audience awareness.

In some universities classes are designed for students from a

single major. For instance, one set of classes will be limited to

engineers, and another to students in business administration.

This approach is being used with success in various parts of the

country and has a number of advantages. Textbooks can focus on

the specific kinds of communication that a student will be working

with in future job situations. Classroom discussion can be

conducted with an assumed level of knowledge in the students'

major. And the teacher can specialize in one area of

communication and may be able to work out cooperative arrangements

with professors in that area.

.~

Howogencous classe~ however, are not as inheLently effect~

in_Qfomoting audience awareness as classes contain~ students_____

from different majors. In many universities a class can obtain

students from such-niajors as animal science, engineering,

accounting, architecture, computer science, horticulture, and

finance. This mix of majors more nearly approximates the mix of

disciplines found in actual working environments. In such

heterogeneous classes, the future accountant has the opportunity

to inform the future industrial engineer that he had difficulty

understanding him, and that kind of confrontation can have far

more impact than the words of a teacher. When, in future years,

the engineer addresses the Executive Committee of his company, one

of whose members is an accountant, his earlier experience with the

21

student in accounting could make him more sensitive to the need

for audience adaptation.

Speeches can also be used to promote audience awareness in

courses for future professionals fn fields-TiKe eng1neErring or

accounting. Each student might be assigned two speeches drawn

from two different writing assignments, perhaps a process paper

and a major report. The audience for these speeches should be his

classmates. Ample time should be set aside at the conclusion of

each speech for a thorough evaluation by the student audience.

Again and again classmates will confront a surprised speaker with

the simple fact that they haven•t understood him. Terms and

concepts that have come to seem commonplace to the speaker, he

discovers, go over the heads of a group of non-specialists. He

attains the realization--occasionally for the first time--that he

has truly become a specialist. Such a bracing experience can

convince him that he must begin developing the techniques that

will enable him to communicate with the whole range of audiences

that he will encounter in his career.

Classes of students intending to become full-time

communicators might also be heterogeneous, and, to the extent that

they are, speeches might also prove effective in suggesting the

importance of audience awareness to them. But my own belief is

that nothing in the classroom can prepare such students for their

future audiences as well as on-the-job experience. For this

reason, at Texas A&M we are encouraging these students to enroll

in our new cooperative education program. Under this program

students work for one or more semesters as full-time communicators

in industry. In such positions they learn the tact that is

necessary in working with an engineer to edit his manuscript.

They learn how difficult it is to acquire information from

professionals who have not learned the techniques of audience

adaptation. They learn how uninformed administrators and other

employees can be about the very organization for which they work.

They learn how much less laymen outside a company know about

company matters. All of these lessons can help motivate students

to attempt to master the techniques of adapting to various

audiences.

The third group of technical writing students, those in

graduate school intending to teach technical communication at

colleges and universities, should not only spend one or more

semesters working in industry but also must concern themselves

with three additional audiences. Like all professors they will be

involved in teaching, research, and service. As teachers, they

will probably--at least at the beginning--devote most of their

time to students from the first group, those future professionals

in fields like engineering and accounting. At Texas A&M we help

these future teachers acquire a sense of their students as an

22

audience by scheduling our graduate course in the teaching of

technical communication after a class of these future

professionals. We involve the graduate students in the

undergraduate class to the greatest extent possible. They correct

all papers--the corrections subject to revision by their

professor--and they have the opportunity for visitation. When the

student has completed the graduate course--if he has successfully

taught Freshman Composition and is currently a Ph.D. candidate--he

may be given the opportunity to teach a class of technical writing

students from the first group, assisted by an advisor from the

technical writing staff. No other experience can give a future

teacher of technical communication as good a grasp of his future

student audience.

If these graduate students are to become publishing scholars,

they need to discover what their scholarly audience already knows.

They need to develop as great an awareness of past and present

research as possible . This need points out a serious omission in

technical writing scholarship to date--the lack of review articles

about research in the field . The recent publication of Teaching

Composition: 10 Bibliographical Essays suggests the value of such

work. This book explores the history of research in composition

as it relates to traditional courses, and it should be on the

shelf of every writing teacher. Unfortunately, it does not

evaluate research in the field of scientific and technical

writing, a serious omission. Years ago Don Cunningham issued a

call for more bibliographical work in our field, and until more

bibliographies and reviews are produced, we will find it difficult

to convey an adequate awareness of scholarly audience to our

graduate students.

Another important future audience for our graduate students

will be their colleagues in English from the various literary

fields. With the demand for courses in business, scientific, and

technical writing growing, future teachers in our field will

increasingly be called on--as part of their service activites--to

develop courses and programs. If they are to obtain approval for

these activities, they usually need at least resignation on the

part of their colleagues . Those involved in such course and

program development are no doubt aware of the negative reactions

that such activities can generate. A few of these reactions are,

I suspect, valid. Too much of the research in our field

represents restatement rather than advance, and evaluations of

publications in our field--where they exist at all--are often not

as rigorous as they might be. BQ! I believe that most negative_

~ions from our colleagues in literary fields stem from an

inadequate understanding of the depth and e~tent of the

___

~le research that now exists in ftelds like traditiona __

l __

composition and scien~ific and technical writing. In addition,

too few literary scholars recognize that we often work in the same

23

A scholar researching the history of scientific and

writing in the seventeenth century may well be working

with the ideas of such scholars are Morris Croll and Richard

Foster Jones, the same ideas used by many scholars of seventeenth

and eighteenth century English literature. Graduate students need

to be made aware that the audience of their colleagues in literary

fields is both important and sensitive.

~reas.

t~~ical

Audience adaptation, then, can provide a foundation for

technical writing courses. A consideration of the concept can

affect the kind of students in a class, the teacher's relationship

with the individual students, the approach to basic subject

matter, decisions about combining speech and writing or

introducing cooperative education programs, and the preparation of

our future professors of technical communication for teaching,

research, and service. If audience is to become the foundation of

technical writing courses, however, more textbooks that emphasize

audience need to be written. Too many textbooks are written

without a clear sense of the kind of students for whom they are

written, and too many neglect even to mention audience adaptation.

Teachers selecting textbooks for the fir-st time should be very

cautious in determining whether a textbook is designed solely for

engineers, primarily for students in business, or for

heterogeneous classes . They should look, too , for an emphasis on

audience adaptation. To help inform textbooks, more research on

the relationship between audience and business, scientific, and

technical writing is needed.

IN TECHNICAL WRITING: THE NEED FOR GREATER REALISM

IN IDENTIFYING THE FICTIVE READER

David L. Carson

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

One of the more distinctive characteristics of technical

writing lies in its traditional emphasis, in the pre-writing

phases, on audience analysis . Certainly all expository writing

must make concessions to the audience if it will be truly

expository, but the functional demands placed upon written

technical communication require considerably more attention to the

audience than is common for many other species within the genre . l

Because, as John Walter has pointed out, "the writer ' s purpose (in

technical writing) is not only to inform but also to provide a

basis for some sort of immediate action,"2 the goals of modern

t~nical writing are ver~ similar to those of Aristotelian

rhetoric.

Although Thomas Wilson, in coming at Aristotle through Cicero

and Quintilian, wrote in 1553, what he had to say about the "end

of rhetorique" is not much different from what most technica 1

communicators would judge as the "end of technical writing."

According to Wilson, the purpose of rhetoric was to treat

All such matters as may largely be expounded for man's

behove ••• [in a way] that the hearers may well know

what he meaneth and understand him wholly , the which

he shall with ease do if he utter his mind in plain

words ••• and tell it orderly without going about

the bush • • • • [For the rhetorician] is ordained to

express the mind that one might understand another's

meaning •••• that [his hearers] shall be forced to

yield unto his saying.3

Obviously, Wilson is exhorting his readers to analyze their

audiences, but even though his own words on the printed page would

spread far beyond the audience he had imagined as he wrote The Art

of Rhetorigue, his approach to audience is primarily bound by time

and space. To him an audience was a group of people whom the

rhetor might a1ready know, or whom the rhetor might get to kn0\'1

from their response to his exordium. Modern communication

technology has, however, made audience analysis a much more

cOMplex task. The more rapidly one may communicate a wide variety

of complex ideas to an exceptionally diverse and widespread

audience, the more difficult is the identification of a particular

person who epitomizes the characteristi~s of the group of people

to whom the writer directs his message.

24

25

THE STATE OF AUDIENCE ANALYSIS IN TECHNICAL COMMUNICATION

At a time in which electronic mass media have developed

audience measurement systems to provide nearly instantaneous and

reputedly accurate data on an audience's reaction to almost any

message, more technical writers operate with no more information

to guide them than was available two decades ago.5 Consequently,

far too many technical writers find themselves forced to rely

solely upon their intuition to create the necessary, if fictive,

construct of the universal audience of one to which they will

write. Worse than this, these same writers often receive only

mini mal feedback from their invisible audiences and hence are

denied opportunity to infuse reality into even their haziest

audience constructs.6

The Audience Is Always Fictive

Although t eachers of technical writing routinely insist that

students write whenever possible to a real audience , no such

"real" audience exists . Even when an author knows very intimately

the person to whom he or she writes , t he image of audience whi ch

the writer carries in his or her mind is merely a fi ctive

construction based upon available data . ?

If this assertion seems to contradict my earlier criticism of

technical communication for its practice of forcing writers to

construct audiences out of whole cloth , I assure you it does not.

To one degree or another, the writer's image of any pa rticular

universal audience of one is always a mere figment of imagination.8

My criticism aims only at those organizations which fail to supply

the writer with the most complete data avai l able upon which to

base an imaginary audience construct .

A Creative Trad1tion

Despite such handicaps, technical writers have exercised

sufficient creatiVity to communicate relatively well to a wide

variety of disparate readers. They have created such forms as the

double report to reach mixed audiences, they have used "plain

words ••• without going about the bush," and they have used

simile, metaphor, analogy, first person point- of- view and even

dialogue to assist them in communicating effect i vely . 9 Moreover ,

technical writers have improved the efficiency of their written

communications by supporting them with illustrations, tables,

graphs, charts, diagrams, special typography, and even audiovisual

supplements.

26

Nevertheless, this creative tradition has been and continues

to be hampered by the inability of technical communication to

establish the writer to a managerial position central to the

communication process. To function with maximum efficiency, a

writer must be able to control a communication project from

inception through dissemination, and he or she must also have the

authority not only to demand pertinent data from a variety of

sources but to define what data in what forms is necessary.

To do this, technical communicators must learn to make use of

the instruments and methods of communication research as they

apply to the assessment of written communication. Although a

writer's image of audience based on empirical data will remain

fictive and hypothetical, the image should begin to approach a

higher order of fictional realism.

EMPIRICAL RESEARCH IN WRITING

For over fifty years scholars from various disciplines have

conducted empirically oriented research on the communicative

effectiveness of expository prose .IO From these studies have come

at least fifty so-called readability formulas. Unfortunately, few

of these can measure much more than sentence length or syllable

density. As a result, a writing sample on a complex subject \'Jhich

contained a high frequency of exceptionally abstract, if short,

technical words might test out at the same readability level as a

ninth grade science text.ll

This is one of the reasons, I suspect, that writers and

teachers of writing have not, generally, made much use of

readability tests beyond accepting the two most useful bits of

information the tests have produced . For better reader

comprehension, use short sentences and short words. Another

reason relates to the fact that readability tests only measure

certain narrow d ~mensions of a prose artifact after it is written

and are hence predictive . Writers and teachers of writing, on the

other hand, are predominantly concerned only with how to or

causal factors in the writing process .12

11

11

Nevertheless, readability formulas are still important

adjuncts to the writer in assessing the aptness of a prose style

for the reading level of its intended audience. This is

particularly true today when computerized word - processing

technologies make automatic readability analysis of a text almost

effortless .13

27

Beyond Readability

Aside from the sheer complexity inherent in analyzing writing

from other than a predictive basis, research in causal analysis is

hampered, as well, by the plethora of narrowly applicable, but

extremely abstract specialized vocabularies within each particular

technology. What this means is that the results of applied

writing research in one technology have tended to be of little

value to another. Hence a two -thousand word vocabulary designed

for the readers of Caterpillar's publications might not be

effective for Data General's readers.

In consequence, the directions which meaningful research will

take should be defined more and more by the agency of greatest

interest, publications management. The following broad scheme

outlines one way in which information flow to the writer might be

improved, and it also outlines as well a method which the

imaginative teacher may use to good advantage in the classroom.

See Note 18.

A PROPOSED APPROACH

As George R. Klare suggests in A Manual for Readable Writing,

a writer in analyzing an audience must take into account two major

variables in addition to reading level:

* The reader's level of competence, and

* The reader's level of motivation.14

Reader Competence

Although, ~s Klare defines it, reader competency consists of