ORIGINAL INVESTIGATION

ONLINE FIRST

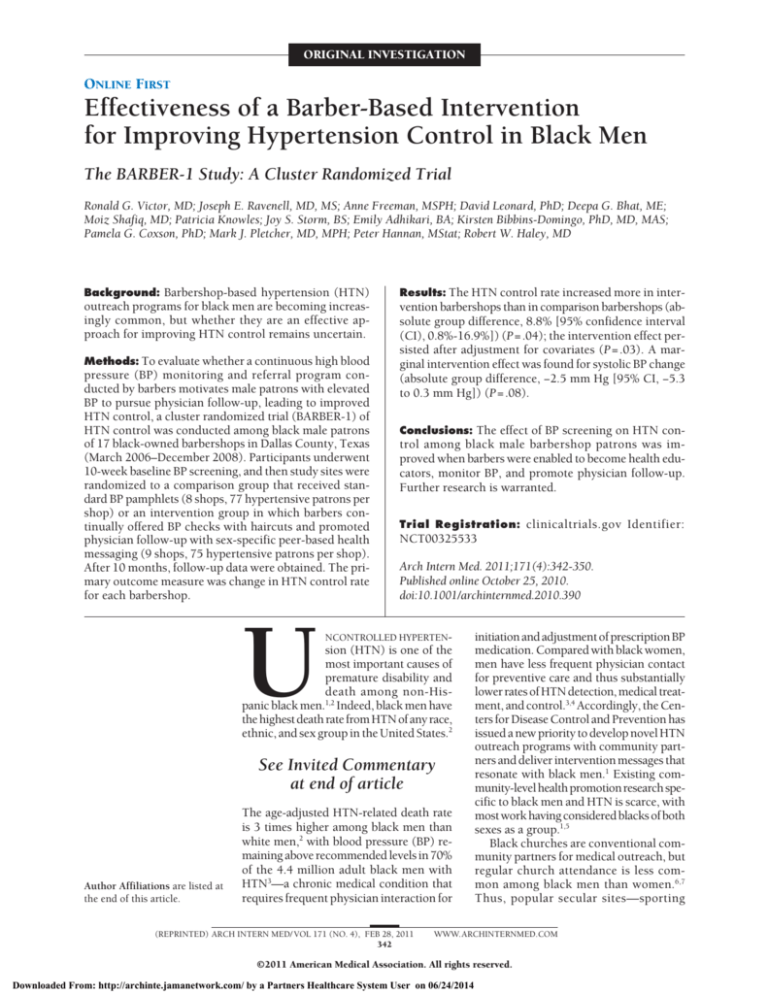

Effectiveness of a Barber-Based Intervention

for Improving Hypertension Control in Black Men

The BARBER-1 Study: A Cluster Randomized Trial

Ronald G. Victor, MD; Joseph E. Ravenell, MD, MS; Anne Freeman, MSPH; David Leonard, PhD; Deepa G. Bhat, ME;

Moiz Shafiq, MD; Patricia Knowles; Joy S. Storm, BS; Emily Adhikari, BA; Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, PhD, MD, MAS;

Pamela G. Coxson, PhD; Mark J. Pletcher, MD, MPH; Peter Hannan, MStat; Robert W. Haley, MD

Background: Barbershop-based hypertension (HTN)

outreach programs for black men are becoming increasingly common, but whether they are an effective approach for improving HTN control remains uncertain.

Methods: To evaluate whether a continuous high blood

pressure (BP) monitoring and referral program conducted by barbers motivates male patrons with elevated

BP to pursue physician follow-up, leading to improved

HTN control, a cluster randomized trial (BARBER-1) of

HTN control was conducted among black male patrons

of 17 black-owned barbershops in Dallas County, Texas

(March 2006–December 2008). Participants underwent

10-week baseline BP screening, and then study sites were

randomized to a comparison group that received standard BP pamphlets (8 shops, 77 hypertensive patrons per

shop) or an intervention group in which barbers continually offered BP checks with haircuts and promoted

physician follow-up with sex-specific peer-based health

messaging (9 shops, 75 hypertensive patrons per shop).

After 10 months, follow-up data were obtained. The primary outcome measure was change in HTN control rate

for each barbershop.

Results: The HTN control rate increased more in intervention barbershops than in comparison barbershops (absolute group difference, 8.8% [95% confidence interval

(CI), 0.8%-16.9%]) (P=.04); the intervention effect persisted after adjustment for covariates (P = .03). A marginal intervention effect was found for systolic BP change

(absolute group difference, −2.5 mm Hg [95% CI, −5.3

to 0.3 mm Hg]) (P =.08).

Conclusions: The effect of BP screening on HTN control among black male barbershop patrons was improved when barbers were enabled to become health educators, monitor BP, and promote physician follow-up.

Further research is warranted.

Trial Registration: clinicaltrials.gov Identifier:

NCT00325533

Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(4):342-350.

Published online October 25, 2010.

doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.390

U

NCONTROLLED HYPERTENsion (HTN) is one of the

most important causes of

premature disability and

death among non-Hispanic black men.1,2 Indeed, black men have

the highest death rate from HTN of any race,

ethnic, and sex group in the United States.2

See Invited Commentary

at end of article

Author Affiliations are listed at

the end of this article.

The age-adjusted HTN-related death rate

is 3 times higher among black men than

white men,2 with blood pressure (BP) remaining above recommended levels in 70%

of the 4.4 million adult black men with

HTN3—a chronic medical condition that

requires frequent physician interaction for

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 171 (NO. 4), FEB 28, 2011

342

initiation and adjustment of prescription BP

medication. Compared with black women,

men have less frequent physician contact

for preventive care and thus substantially

lower rates of HTN detection, medical treatment, and control.3,4 Accordingly, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has

issued a new priority to develop novel HTN

outreach programs with community partners and deliver intervention messages that

resonate with black men.1 Existing community-level health promotion research specific to black men and HTN is scarce, with

most work having considered blacks of both

sexes as a group.1,5

Black churches are conventional community partners for medical outreach, but

regular church attendance is less common among black men than women.6,7

Thus, popular secular sites—sporting

WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

©2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ by a Partners Healthcare System User on 06/24/2014

events and barbershops—have been approached for HTN

outreach to a larger segment of the at-risk male population.8,9 Black-owned barbershops hold special appeal for

community-based intervention trials because they are a

cultural institution that draws a large and loyal male clientele and provides an open forum for discussion of numerous topics, including health, with influential peers.10-12

Barbershop-based HTN outreach programs are becoming common nationwide,1,13-17 but whether they are an

effective approach for improving HTN control among

black men is unknown owing to a dearth of evaluation

research. Interventions described in the peer-reviewed

literature previously had no evaluation component.

In recent nonrandomized feasibility studies, our research group11 found that a program of continuous BP monitoring and peer-based health messaging in a barbershop can

(1) increase physician referrals and lower BP among longterm patrons with uncontrolled HTN and (2) be implemented by barbers rather than research personnel. Based

on the encouraging pilot data, we designed and conducted

a cluster-randomized trial—the Barber-Assisted Reduction in Blood Pressure in Ethnic Residents (BARBER-1)

study.18 To our knowledge, BARBER-1 is the first randomized controlled trial of a barbershop-based health promotion program. The intent was to use the nature of blackowned barbershops—haircut service and socialization—to

have barbers become promoters of physician follow-up for

BP control. We chose the cluster-randomized trial, knowing that the design needed to avoid contamination between intervention and comparison conditions, and analysis must allow for possible dependency of response between

individual patrons within a barbershop as well as withdrawals and additions of individual patrons over time.19-21

METHODS

All black men attending the participating barbershops were offered 10-week baseline BP screenings for HTN. Study sites were

then randomized to a comparison group of barbershops that

received standard HTN education pamphlets written for a broad

audience of black men and women or an intervention group

in which barbers continually offered their entire male clientele BP checks with haircuts and used personalized sexspecific peer-based health messaging to promote physician follow-up. Intervention barbershop patrons received this message

repeatedly from both day-to-day conversations with their barbers (and other male patrons) and large role-model posters on

the shop walls showing their own male peers (actual patrons

of their barbershop) modeling specific HTN treatmentseeking behavior and using their own words to tell the story.

After 10 months, follow-up data were collected to determine if

barbershops randomized to the intervention arm showed a larger

improvement in HTN control rates (percentage of a barbershop’s hypertensive patrons with recommended BP levels).

PARTICIPATING BARBERSHOPS

The trial was conducted in black-owned barbershops with 95%

or greater black male clientele in Dallas County, Texas, from

March 2006 to December 2008 (Figure 1 and Figure 2 and

eFigure 1, http://www.archinternmed.com). Fifty-five of 222

shops met additional selection criteria (in business for ⱖ10 years

and employing ⱖ3 barbers). We selected 18 of these to repre-

222 Black-owned barbershops assessed

for eligibility in Dallas County, Texas∗

204 Barbershops excluded

167 Not meeting additional

inclusion criteria†

37 Eligible but not

selected for other

reasons‡

18 Barbershops enrolled

1 Barbershop lost to follow-up

(went out of business)

17 Barbershops randomized

Baseline§

9 Barbershops allocated to

barber-based intervention

695 Patrons with HTN

(mean, 77/shop, range 37-163)

1 Barbershop lost to

follow-up (barbers

decided not to participate

in intervention)

37 Patrons with HTN

Baseline§

8 Barbershops allocated to

educational pamphlets

602 Patrons with HTN

(mean, 75/shop, range 30-165)

1 Barbershop lost to

follow-up (excluded

due to concern for

staff safety)

78 Patrons with HTN

Intervention implemented||

10 Months

Pamphlets distributed¶

10 Months

Follow-up#

8 Barbershops included in

analysis

539 Patrons with HTN

(mean, 67/shop, range 30-123)

Follow-up#

7 Barbershops included in

analysis

483 Patrons with HTN

(mean, 69/shop, range 23-149)

Figure 1. Flow diagram for the design of the Barber-Assisted Reduction in

Blood Pressure in Ethnic Residents (BARBER-1) Study.18 HTN indicates

hypertension. *Eligible barbershops had non-Hispanic black owners and

barbers and had a greater than 95% black male clientele. †Barbershops had

been in business for 10 or more years and had 3 or more barbers. ‡Other

reasons for not selecting barbershops included 9 or more barbers per shop;

inadequate space to accommodate study staff; barber stations separated by

walls (inadequate space for peer group influence); and insufficient grant

funds to enroll a larger number of shops from each geographic quadrant.

§Black field interviewers administered the baseline health questionnaire and

measured blood pressure on adult black male patrons entering the

barbershops for 10 weeks to identify those with confirmed HTN and obtain

accurate estimates of their baseline blood pressure levels. Patrons found to

have elevated blood pressure readings were given written recommendations

for physician follow-up. 㛳Barbers were paid for offering a blood pressure

check to each adult black male patron at every haircut for 10 months and for

facilitating physician follow-up for patrons they identified as having elevated

blood pressure readings. ¶Barbershops in the comparison group were given

a continual supply of lay education pamphlets from the American Heart

Association on HTN in blacks for 10 months. ⲆBlack field interviewers

collected the follow-up data for 10 weeks following completion of the

10-month intervention period.

sent 4 geographic sectors with sizeable black populations. All

18 initially agreed to participate, but 1 shop went out of business prior to randomization; 1 intervention shop dropped out

before the intervention began; and 1 shop assigned to the comparison group was eliminated on safety concerns (criminal activity in the shop). Randomization was stratified by baseline

HTN control rate and sector. Randomization was blinded.

By the nature of the study, barbers and patrons could not

be blinded after randomization; therefore, the evaluation data

were collected by independently contracted field interviewers

who were not invested in the study’s outcome. The study was

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 171 (NO. 4), FEB 28, 2011

343

WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

©2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ by a Partners Healthcare System User on 06/24/2014

Baseline Data Collection in 9 Intervention Barbershops

3004 Patrons approached and

eligible for first BP screening∗

Baseline Data Collection in 8 Comparison Barbershops

2090 Patrons approached and

eligible for first BP screening∗

1947 Excluded from analysis

349 Refused first BP screening

1600 Not hypertensive at first

BP screening

1055 Patrons with HTN at first

BP screening†

1236 Excluded from analysis

69 Refused first BP screening

1167 Not hypertensive at first

BP screening

854 Patrons with HTN at first

BP screening†

360 Excluded from analysis

171 Lost to follow-up

74 Did not complete second

BP screening

115 Not hypertensive at second

BP screening

695 Patrons with confirmed HTN‡

252 Excluded from analysis

128 Lost to follow-up

43 Did not complete second

BP screening

81 Not hypertensive at second

BP screening

602 Patrons with confirmed HTN‡

Follow-up Data Collection in 8 Intervention Barbershops

1669 Patrons approached and

eligible for first BP screening∗

Follow-up Data Collection in 7 Comparison Barbershops

1547 Patrons approached and

eligible for first BP screening∗

995 Excluded from analysis

66 Refused first BP screening

929 Not hypertensive at first

BP screening

674 Patrons with HTN at first

BP screening†

954 Excluded from analysis

85 Refused first BP screening

869 Not hypertensive at first

BP screening

593 Patrons with HTN at first

BP screening†

135 Excluded from analysis

70 Lost to follow-up

43 Did not complete second

BP screening

22 Not hypertensive at second

BP screening

539 Patrons with confirmed HTN‡

110 Excluded from analysis

43 Lost to follow-up

17 Did not complete second

BP screening

50 Not hypertensive at second

BP screening

483 Patrons with confirmed HTN‡

Figure 2. Identification of barbershop patrons with HTN at baseline and follow-up in intervention and comparison groups. HTN indicates hypertension; BP, blood

pressure. *Patrons eligible for BP screening were non-Hispanic black men aged 18 years or older (no upper age limit). Race/ethnicity was self-assigned.

†Screening criteria for HTN were self-reported prescription for BP medication or a measured BP higher than 135/85 mm Hg for patrons without self-reported

diabetes or higher than 130/80 mm Hg for those with diabetes. Patrons meeting screening criteria were offered an incentive for returning another day to (1)

complete a second set of BP readings and a health interview and (2) to bring their prescription pill bottles to the barbershop for interviewers to transcribe

medication data from prescription labels. Each incentive was a free haircut. ‡Hypertension was confirmed if patrons meeting screening criteria had elevated BP on

both days or provided a pill bottle with a current prescription for BP medication.

approved by the institutional review boards of University of

Texas Southwestern Medical Center and Temple University Institute for Survey Research, which conducted the evaluation.

Patron consent was obtained, and data were collected and stored

in accordance with the guidelines of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

INTERVENTION AND COMPARISON GROUPS

Before randomization, both groups of hypertensive patrons were

treated identically: they had 2 baseline BP screenings performed by field interviewers who provided the patrons with written screening results and standard written recommendations

for physician follow-up. After randomization, comparison barbershops received standard pamphlets written by the Ameri-

can Heart Association (High Blood Pressure in African Americans, product code 50-1466). No BPs were measured in the

comparison barbershops for 10 months.

In contrast, the intervention barbershops received no pamphlets, but for 10 months the barbers continually offered BP

checks during haircuts (eFigure 2). In addition, personalized

sex-specific peer-based health messaging was provided—both

through conversations with barbers and other male patrons and

through peer role-model stories18 consisting of large posters

placed on the barbershop walls depicting authentic stories of

other male hypertensive patrons of the same shop modeling the

desired treatment-seeking behavior and using the model’s own

words to tell the story (eFigure 3).

The intervention’s theoretical underpinning was adapted from

the successful AIDS Community Demonstration Projects22 that

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 171 (NO. 4), FEB 28, 2011

344

WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

©2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ by a Partners Healthcare System User on 06/24/2014

mobilized community peers to deliver intervention messages (specific action items) with role model stories and made medical equipment available in the daily environment. Here we trained,

equipped, and paid barbers to make BP monitoring and interpretation available to every adult black male patron with every

haircut in intervention barbershops and to deliver the main intervention message that each patron with an elevated BP reading needs to follow-up with a physician. The barbers encouraged patrons with an established physician to make a follow-up

appointment and referred those without physicians to the project

nursing staff, who facilitated insurance-appropriate referral to

local community physicians and safety net clinics, including the

University of Texas Southwestern Hypertension Specialty Clinic

staffed by physicians who were part of the study. The barbers

also gave the patrons with elevated BP readings wallet-sized referral cards to give their physicians ongoing feedback—

accurate out-of-office BP readings—about the need to start or

intensify BP medicine regimens (eFigure 4).

In the intervention barbershops, barbers were paid $3 per

recorded BP, $10 per phone call requesting nurse-assisted

physician referral, and $50 per BP card returned (by the

patron to the barber) with the physician’s signature (documenting physician-patient interaction—the study’s major

behavioral objective). Patrons received a free $12 haircut for

each high BP referral card signed by their physician and

returned to their barber.

on the second day were averaged to obtain a stable mean value,4,7

which was used to calculate BP outcomes.

Hypertension was defined as having either (1) a documented current prescription for BP medication or (2) for untreated patrons, a measured BP of 135/85 mm Hg or higher for

men without diabetes and 130/80 mm Hg or higher for those

with diabetes (recommended cutoff values for out-of-office BP24).

Control of HTN was defined as BP levels below these limits. In

each barbershop, the percentage of hypertensive patrons having goal BP values was calculated at both ends of the study. The

primary outcome, calculated for each barbershop, was the change

in HTN control rate. Prespecified secondary outcomes included barbershop-level changes in HTN treatment rates, HTN

awareness rates, and BP levels.

The study was designed to have 80% power for detecting a

15% absolute mean difference in improvement in HTN control

rate between study groups.18 Power calculations assumed 8 shops

per study arm, 100 hypertensive patrons per shop, and an overtime correlation of 0.1. However, the actual over-time correlation was about 1 (as shown for the intraclass correlation for change

of 0 in eTable 1), indicating that the study design provided more

statistical power than anticipated. The power was driven mainly

by the number of barbershops once the number of hypertensive

individuals exceeded about 50 per barbershop; thus, differences in the range of 70 to 100 had only a minor effect.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

OUTCOME EVALUATION

Several steps were taken to rigorously evaluate the study’s primary outcome—the change in HTN control rates for shops in each

study arm. Baseline and 10-month follow-up BP measurements

and computer-assisted health interviews were conducted not by

the barbers but rather by independently contracted, trained black

field interviewers. The HTN control rates were derived from a second set of multiple BP measurements and prescription pill bottle

labels rather than the 1 or 2 BP measurements and subjective treatment reporting typically used in survey research.

For 10 weeks at both ends of the study, interviewers offered free BP screenings to all adult black men entering the barbershop. Men meeting screening criteria for HTN (measured

BP of ⬎135/85 mm Hg [⬎130/80 mm Hg for diabetic patrons]

or reported use of BP medication) were asked to return another day to (1) complete a second set of BP measurements and

a health questionnaire, and (2) bring their pill bottles to the

barbershop for interviewers to transcribe medication data. The

questionnaire consisted of structured response items from previously validated instruments on numerous covariates, including age (years), education beyond high school (yes/no), marital status (yes/no), and current smoking status (yes/no). An

additional covariate, an indicator for participation in baseline

and follow-up surveys, was constructed by merging the baseline and follow-up unique identifiers. These covariates were included in an adjusted analysis of the primary outcome because of their plausible influence on health care–seeking behavior

and BP.

Interviewers were trained on proper BP measurement technique.23,24 They measured BPs using validated oscillometric monitors (Welch Allyn, Arden, North Carolina),25 with patrons seated

after 5 minutes of rest. For each subject, the appropriately sized

arm cuff was determined, recorded, and used for all subsequent

BP measurements. For both baseline and follow-up data, field

interviewers took 6 consecutive BP readings on each hypertensive subject on each of 2 days. Measurements on each first monitoring day are known to be higher and unstable and therefore

were excluded, as recommended by current guidelines23,24 and

substantiated by preparatory field work.11 The final 4 readings

Because of the cluster design, summary statistics are presented

as the means (standard errors of barbershop means [SEMs]). A

difference between study arms at baseline was tested with a mixed

effects regression model with study arm as a fixed effect and barbershop within the arm as a random effect. A difference between study arms over time was tested with a mixed-effects regression model with arm, time, and arm⫻time as fixed effects

and barbershop, barbershop⫻time, and patron within barbershop as random effects. The random effects of barbershop and

barbershop⫻time account for the clustering of outcome levels

and changes within barbershops, while the random effect of patron within barbershop accounts for repeated measures of clients present at both baseline and final assessment periods. These

models simultaneously estimate the outcome measure in both

study arms at both time points; the arm⫻time effect tests the

intervention effect, thereby adjusting for baseline values.19,20 Generalized linear mixed models with logit link functions were used

for binary outcome variables, and linear mixed models were used

for continuous outcome variables. Adjusted models were fit with

centered, individual-level covariates included as additional fixed

effects.20 Model-based significance levels and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were obtained. P⬍.05 was considered statistically

significant. Analyses were conducted using SAS/STAT software, version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

COST-EFFECTIVENESS SIMULATION

We used the CHD (Coronary Heart Disease) Policy Model—an

established computer-simulation, state-transition (Markov cohort) model of CHD incidence, prevalence, mortality, and costs

in the US population27-29—to simulate the average benefits of

the observed systolic BP reduction in BARBER-1 on the numbers of adverse events prevented and associated health care cost

savings during a 1-year intervention. The total cost savings figure provides an estimate of how much could be spent on intervention implementation plus antihypertensive treatment for

the program to be cost-neutral in the first year. Details on methods and model population characteristics are provided in eTable

2 and eTable 3.

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 171 (NO. 4), FEB 28, 2011

345

WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

©2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ by a Partners Healthcare System User on 06/24/2014

Table 1. Characteristics of Black Barbershops and Black Male Patrons With HTN a

Baseline

Intervention

(n = 9 shops)

Characteristic

Barbers per shop, mean (range), No.

Patrons with HTN per shop, mean (range), No.

Total No.

Age, mean (SEM), y

Married or living with partner

Level of education

ⱕHigh school

College

Postgraduate

Full-time employment

Income, % of the poverty level c

ⱕ100

101-300

301-500

⬎500

Primary medical care provider

Health insurance status d

Any policy

HMO or private

Veterans Affairs

Medicare

Medicaid

Safety net

Barbershop patronage

Duration of patronage, mean (SEM), y

Time between haircuts, mean (SEM), wk

Cardiac risk factors and history e

Family history of HTN

Current smoker

BMI, mean (SE)

Diabetes

High cholesterol level

Prior stroke, MI, and/or heart failure

Chronic renal failure

Barbershops

5 (3-7)

77 (37-163)

Follow-up

Comparison

(n = 8 shops)

Intervention

(n = 8 shops)

Comparison

(n = 7 shops)

4 (3-6)

75 (30-165)

4 (2-5)

67 (30-123)

3 (2-5)

69 (23-149)

Patrons With HTN

695

602

49.5 (2.4)

51.2 (2.6)

431 (67.3) b

388 (56.7) b

539

51.8 (2.0)

344 (65.1)

483

54.0 (2.3)

349 (69.1)

342 (46.9)

293 (43.4)

59 (9.7)

403 (61.6)

241 (38.9)

279 (48.0)

82 (13.1)

354 (64.5)

266 (49.7)

216 (40.5)

57 (9.8)

322 (64.1)

169 (32.4)

232 (51.6)

81 (16.0)

292 (68.8)

110 (15.8)

209 (29.8)

237 (36.0)

116 (18.4)

558 (80.5)

76 (12.0)

145 (26.3)

202 (33.4)

170 (28.4)

527 (84.9)

69 (12.9)

144 (27.5)

202 (39.2)

111 (20.4)

463 (84.5)

45 (9.2)

107 (21.2)

177 (37.9)

148 (31.7)

448 (91.3)

587 (85.3)

458 (68.6)

80 (10.2)

94 (11.4)

47 (6.4)

31 (3.9)

524 (84.6)

421 (70.7)

84 (12.1)

88 (10.3)

45 (6.7)

23 (2.9)

470 (85.7)

352 (67.0)

76 (12.5)

104 (15.6)

47 (9.8)

28 (4.2)

443 (89.6)

349 (73.5)

77 (12.8)

98 (14.7)

39 (6.2)

20 (4.4)

7.4 (1.3)

3.8 (0.4)

9.7 (1.7)

3.2 (0.3)

7.9 (1.0)

2.9 (0.2)

9.7 (1.8)

2.8 (0.2)

576 (83.3)

159 (22.1)

31.4 (0.5)

144 (19.2)

311 (44.2)

103 (13.0)

11 (1.4)

505 (84.0)

104 (17.5)

30.7 (0.4)

136 (19.1)

297 (44.8)

86 (12.9)

14 (1.8)

443 (84.2)

128 (25.1)

31.8 (0.7)

123 (22.8)

281 (52.6)

100 (15.1)

7 (1.3)

423 (88.5)

88 (19.1)

30.6 (0.4)

134 (25.1)

278 (56.8)

72 (12.8)

14 (2.1)

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); HMO, health maintenance organization;

HTN, hypertension; MI, myocardial infarction.

a Unless otherwise indicated, data are reported as number (percentage) of barbershop patrons. Percentages are reported as means of barbershop means.

b Significant group difference at baseline (P=.01).

c The 2007 United States poverty level was $10 210 for a single person and $20 650 for a 4-person household; “middle-income” was defined as 300% of the

poverty level.26

d Some patrons held multiple insurance policies.

e Data are self-reported.

RESULTS

The characteristics of the participating barbershops and the

patrons with HTN are summarized in Table 1. The groups

were well balanced at baseline across most characteristics.

However, at baseline, a higher percentage of patrons in the

comparison group reported being married (P=.01).

Although at baseline 85% of the hypertensive patrons in both groups reported having health insurance

(mostly private insurance) and middle-income levels

(Table 1), HTN was uncontrolled in most affected patrons. Overall, 45% of the subjects screened had HTN,

and of these, 78% were aware of their diagnosis; 69% were

being treated for it; and only 38% had their BP controlled. These rates are all slightly higher than recent na-

tional estimates (eTable 4). Baseline HTN control rates

were not significantly different between study groups

(P=.22) but tended to be lower in the intervention group

(33.8% vs 40.0%) (Table 2 and Figure 3).

PRIMARY OUTCOME

Table 2 details the change over time in the primary and

secondary outcomes. Figure 3 shows the barbershopspecific changes over time in HTN control rates. In

unadjusted analysis that used all available data (17 barbershops at baseline, 15 at follow-up), the enhanced

barber-based intervention resulted in a greater improvement in the primary outcome of HTN control rate than

the comparison treatment: absolute group difference,

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 171 (NO. 4), FEB 28, 2011

346

WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

©2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ by a Partners Healthcare System User on 06/24/2014

Table 2. Mean Change in HTN Control Rate and Its Components in Barbershops Randomized to Intervention

and Comparison Conditions a

Intervention Group

Characteristic

Absolute

Change, %

(95% CI)

Baseline Follow-up

Control rate d among all

patrons with HTN

Control rate d among treated

patrons with HTN e

HTN treatment rate

HTN awareness rate

Systolic BP, mm Hg

Diastolic BP, mm Hg

BP medications per patron

with HTN

Comparison Group

Baseline Follow-up

33.8

53.7

19.9 (14.4 to 25.4)

40.0

51.0

49.1

65.9

16.8 (10.0 to 23.5)

57.1

64.3

67.9

79.5

137.6

81.5

1.4

79.0

86.3

129.8

78.7

1.8

11.2 (7.3 to 15.0)

6.8 (3.3 to 10.3)

−7.8 (−9.7 to −5.9)

−2.8 (−4.0 to −1.6)

0.5 (0.3 to 0.6)

69.9

79.1

136.4

80.0

1.4

76.1

85.4

131.1

78.1

1.7

Intervention Effect

Absolute

Change, %

(95% CI)

Absolute Group

Difference, %

(95% CI)

11.1 (5.2 to 16.9)

8.8 (0.8 to 16.9)

.04

.03

9.6 (−0.3 to 19.5)

.06

.05

6.2 (2.1 to 10.3)

5.0 (−0.6 to 10.6)

6.4 (2.5 to 10.2)

0.4 (−4.8 to 5.7)

−5.3 (−7.4 to −3.2) −2.5 (−5.3 to 0.3)

−1.9 (−3.2 to −0.6) −0.9 (−2.6 to 0.8)

0.3 (0.1 to 0.4)

0.2 (0.0 to 0.4)

.10

.72

.08

.28

.07

.33

.57

.09

.18

.09

7.1 (−0.1 to 14.4)

P

Adjusted

Value b P Value c

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; HTN, hypertension.

a Unless otherwise indicated, data are reported as percentage of barbershop patrons with HTN.

b P values were determined by mixed logistic regression for dichotomous study outcomes and by mixed linear regression for continuous outcomes in analyses that

used all available data (17 barbershops at baseline and 15 barbershops at follow-up).

c Adjusted for effects of age, education, marital status, smoking status, and participation in both baseline and follow-up cohorts.

d The HTN control rate is the percentage of hypertensive patrons with BP below recommended out-of-office values (135/85 mm Hg for patrons without diabetes and

130/80 mm Hg for those with diabetes).

e Patrons with HTN receiving prescription BP medication.

Δ = 8.8% (3.7%)

(P = .04)

100

A

B

100

Δ = 11.1% (2.7%)

(P < .001)

HTN Control Rate, %

Δ = 19.9% (2.5%)

(P < .001)

75

75

50

50

25

25

0

0

Baseline

Follow-up

Baseline

Intervention

Follow-up

Comparison

Figure 3. Baseline and follow-up hypertension (HTN) control rates for individual barbershops in intervention (A) and comparison (B) groups. Delta symbol

indicates change in HTN control rate, reported as mean (SEM). Paired data are shown for each barbershop except for 1 barbershop in each group lacking

follow-up data (black squares). Boxes with error bars indicate group means (SEMs). The significance of the intervention effect on HTN control was not affected by

adjustment for baseline blood pressure, age, marital status, college education, smoking status, and participation at both baseline and follow-up (P=.03).

8.8% (95% CI, 0.8%-16.9%) (P=.04); the intervention

effect persisted after adjustment for covariates (P=.03).

In addition, in a conservative intention-to-treat analysis,

which assumed that the 2 barbershops lost to follow-up

(1 per arm) both followed the lesser trajectory of the

comparison barbershops, the resultant intervention

effect was 7.8% (95% CI, 0.4%-15.3%) (P=.04).

SECONDARY OUTCOMES

Borderline intervention effects were observed for several secondary outcomes (Table 2), including systolic BP

reduction: absolute group difference, −2.5 mm Hg (95%

CI, −5.3 to 0.3 mm Hg) (P =.08). However, there was no

evidence for an intervention effect on HTN awareness.

Process Data on Intervention Implementation,

Penetration, Incentive Payments, and Acceptability

In the intervention group, follow-up data were collected

on 539 patrons with HTN served by 29 participating barbers in 8 barbershops completing the study. Of the 539

patrons, 275 reported that during the intervention, their

barbers discussed a model story during every haircut (51%);

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 171 (NO. 4), FEB 28, 2011

347

WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

©2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ by a Partners Healthcare System User on 06/24/2014

175 reported that their barbers discussed a story during

half of their haircuts (32%); and 89 reported that their barbers never discussed one (17%). The barbers measured BP

for 417 of the 539 hypertensive patrons (77%), recording

3350 sets of BPs (8 sets per patron), and successfully counseled 180 of 350 patrons with elevated BP readings to have

documented physician visits (51%) (including 36 documented nurse-assisted referrals).

The mean total incentive payment was estimated at $133

per hypertensive patron, calculated as follows: barbers were

paid $60 474 in total for intervention activities for 539 hypertensive patrons ($112 per patron). These patrons returned 939 signed physician-referral cards to the barbers

and received 1 free $12 haircut per card ($21 value per

patron). In the intervention group, 530 of the 539 hypertensive patrons completing the study (98%) and all 29 participating barbers reported that they would like the barberbased intervention program continued indefinitely.

Cost-effectiveness Simulation

If the intervention could be implemented in the approximately 18 000 black-owned barbershops in the United

States (eTable2) to reduce systolic BP by 2.5 mm Hg in

the approximately 50% of hypertensive US black men who

patronize these barbershops (N=2.2 million persons), we

project that about 800 fewer myocardial infarctions, 550

fewer strokes, and 900 fewer deaths would occur in the

first year alone, saving about $98 million in CHD care

and $13 million in stroke care (but offset by $6 million

in additional non-CHD costs contributed by persons who

would otherwise have died). For this intervention to be

cost-neutral from a health care system perspective, therefore, the program costs (including performance incentives, medication, and other health care delivery costs)

could be as high as about $5800 per barbershop or about

$50 per hypertensive barbershop patron.

COMMENT

Black-owned barbershops are rapidly gaining traction as

potential community partners for health promotion programs targeting HTN as well as diabetes, prostate cancer, and other diseases that disproportionately affect black

men.1,11,13-17,30 Yet to our knowledge, the effectiveness of

barber-based HTN screening and referral programs on

BP control previously has not been evaluated by a randomized trial. In this cluster-randomized controlled trial,

we found that an enhanced intervention program—in

which barbers continuously monitored BP and actively

promoted physician follow-up with personalized sexspecific messages—resulted in improved BP control

among black male barbershop patrons with HTN. Although BP control also improved in the comparison group,

which received standard written information about high

BP, the improvement was greater with the enhanced intervention. A marginal intervention effect was seen for

medication treatment rates, BP levels, and other secondary outcomes. Thus, the results of this study provide the

first evidence for the effectiveness of a barber-based intervention for controlling HTN in black men and indi-

cate that more research is needed to develop a highly effective and sustainable intervention model prior to largescale program implementation.

We detected a positive intervention effect despite an

unexpectedly large improvement in BP control in the comparison group, which was not an inactive comparator.

In collecting thorough baseline BP data, we unavoidably intervened in both groups: patrons with HTN in all

participating barbershops were repeatedly exposed to research staff measuring their BP at 2 baseline haircut visits. For ethical reasons, those with elevated BP readings

in both groups were given detailed written recommendations for physician follow-up. In addition to this Hawthorne effect, educational pamphlets written for black individuals were distributed only to comparison shops.

The larger improvement in HTN control seen in the

intervention group is not explained by baseline values,

which were taken into account by the mixed-effects model.

Moreover, within either group, barbershops with lower

baseline values did not show larger increments in HTN

control, and there was no ceiling effect.

The new data confirm and extend earlier pilot data11

by indicating that the characteristic long-term patronage

in black-owned barbershops (almost a decade) and frequent haircut visits (1 every 3-4 weeks) provided much

opportunity for barbers to repeatedly monitor BP and deliver intervention messages. The process data indicate that,

in general, the intervention was implemented as intended with reasonably high levels of intervention implementation and penetration: barbers measured BP on 3 of

every 4 patrons with HTN, and each of the participating

patrons averaged 8 barber BP checks in 10 months. The

barbers motivated 50% of their patrons with elevated BP

readings to visit a physician, supporting the theoretical underpinning of the behavior theory–based intervention,

namely that barbers, as influential peers, can increase HTN

treatment–seeking behavior. The intervention effect on primary and secondary BP outcomes may have been larger

than observed if barbers had motivated the other 50% of

high-BP patrons to see a physician.

A salient finding is the middle-income status of the

barbershop clientele. Although most participating barbershops were in low-income areas, patrons need financial resources to afford frequent haircuts. Because socioeconomic status and affordability of health insurance are

major determinants of HTN control,1 the low baseline

HTN control rates among the barbershop patrons may

seem disproportionate to income level and health care

access. However, for reasons that require more study,

middle-income status alone does not protect black men

from many poor health indicators, including underutilization of available medical services to control HTN and

prevent its complications.31 For example, sociocultural

factors related to masculinity (such as a desire to avoid

showing vulnerability) also can deter men from fully utilizing available preventive medical services.4,31 Our data

suggest that barbers can deliver health messages that resonate with men and, more broadly, that the barbershop

constitutes a unique opportunity for further research on

improving the health status of this particularly vulnerable and understudied group of men—middle-income

black men.1,31

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 171 (NO. 4), FEB 28, 2011

348

WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

©2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ by a Partners Healthcare System User on 06/24/2014

Our study has several important limitations. The impact of the barber-based intervention was less than optimal because not all barbers participated fully, and not all

patrons agreed to have their BP monitored and be referred for physician follow-up. Because study sites were

confined to 1 county, the results cannot be generalized to

other geographic areas without further study. Because the

barbershops’ clientele were predominately middleincome, the intervention had limited ability to reach very

low-income individuals who will require other types of intervention. The evaluation strategy provided a snapshot

of BP improvement at a point in time and does not demonstrate whether the outcomes are sustainable, particularly because financial incentives were paid to barbers for

conducting the intervention and to patrons for following

their advice in seeking medical attention. However, the $112

incentive paid per barber per hypertensive patron and the

$21 paid per patron in free haircuts for HTN-related physician visits is far less than the $750 cash incentive per patient used in a recent smoking-cessation study.32

Because hypertensive patrons chose their individual

physicians, we could not collect actual data on increased

antihypertensive treatment costs associated with the intervention. Our CHD Policy Model simulation indicates

that the projected cost savings from reduced HTNrelated cardiovascular disease (CVD) events in the first

year alone would substantially offset intervention costs.

More extensive simulations are needed to project the cost

savings and quality-adjusted life-years from reduced CVD

that would accumulate beyond the first year (eg, longterm care savings from prevented strokes), particularly

if the modest reductions in systolic BP observed in

BARBER-1 could be sustained or augmented in this highrisk black male population.29,33,34

Despite these limitations, the study establishes an important precedent for future quantitative evaluation research on this and other health promotion programs in

barbershops. The results provide proof of concept for 1

effective barber-based intervention, which lowered systolic BP by about 8 mm Hg from baseline—2.5 mm Hg

more than in the comparison group. Based on the observed intervention effect of an 8.8% greater improvement in HTN control rate, we estimate that 12 hypertensive black male patrons would need to be exposed to this

intervention to achieve BP control in 1 more patron.

The study addresses the newly recommended policy

shift away from a traditional case-management system toward novel population-based systems and communitybased support for persons with HTN.35 The data add to

an emerging literature on the effectiveness of community

health workers in the care of people with HTN36: contemporary barbers constitute a unique workforce of community health workers whose historical predecessors were

barber-surgeons.37 Future studies should evaluate the

potential effectiveness of the intervention in other urban

centers, alternative incentive structures, comparative effectiveness of the intervention with and without certain

components (eg, model stories), and projected long-term

cost-effectiveness of alternative strategies (eg, targeting

barbershops with a mainly older clientele to enhance

screening efficiency and prevent more HTN-related events).

The public health potential is intriguing.

Accepted for Publication: August 21, 2010.

Author Affiliations: Divisions of Hypertension (Drs Victor,

Ravenell, and Shafiq and Mss Knowles and Storm) and Epidemiology (Dr Haley), Department of Health Care Sciences,

the Community Prevention and Intervention Unit (Ms Freeman),andDepartmentsofClinicalScience(DrLeonard)and

Internal Medicine (Ms Bhat), University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas (Ms Adhikari); Departments of

Medicine(DrsBibbins-Domingo,Coxson,andPletcher)and

Epidemiology and Biostatistics (Drs Bibbins-Domingo and

Pletcher), University of California at San Francisco; and Department of Epidemiology and Community Health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis (Mr Hannan). Dr Victor is

now with the Heart Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center,

Los Angeles, California. Dr Ravenell is now with the Department of General Internal Medicine, New York University,

New York. Dr Shafiq is now with the Department of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, University of Florida, Jacksonville. Ms Storm is now with Texas A&M College of Medicine, College Station.

Published Online: October 25, 2010. doi:10.1001

/archinternmed.2010.390

Correspondence: Ronald G. Victor, MD, Hypertension

Center, Cedars-Sinai Heart Institute, 8700 Beverly Blvd,

South Tower Room 5702, Los Angeles, CA 90048 (Ronald

.Victor@cshs.org).

Author Contributions: Dr Victor had full access to all of

the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study

concept and design: Victor, Freeman, Leonard, Bhat, Knowles,

and Haley. Acquisition of data: Victor, Ravenell, Shafiq,

Knowles, and Storm. Analysis and interpretation of data: Victor, Ravenell, Leonard, Bhat, Adhikari, Bibbins-Domingo,

Coxson, Pletcher, Hannan, and Haley. Drafting of the manuscript: Victor, Bhat, Shafiq, Knowles, Storm, and Adhikari.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual

content: Victor, Ravenell, Freeman, Leonard, Bhat, BibbinsDomingo, Coxson, Pletcher, Hannan, and Haley. Statistical analysis: Leonard, Bhat, Hannan, and Haley. Obtained

funding: Victor and Freeman. Administrative, technical, and

material support: Ravenell, Shafiq, Knowles, Storm, and Adhikari. Study supervision: Victor and Freeman. Cost-effectiveness modeling: Bibbins-Domingo and Pletcher. Mathematical modeling: Coxson.

Financial Disclosure: Dr Victor has served on the speaker’s bureau for Pfizer Inc and received an investigatorinitiated research grant from Pfizer and an unrestricted

educational grant from Biovail.

Funding/Support: The BARBER-1 study was supported by

research grant RO-1 HL080582 from the National Heart

Lung and Blood Institute (Dr Victor) and by grants from

the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation (Dr Victor), the Aetna

Foundation Regional Healthy Disparity Program (Dr Victor), Pfizer (Dr Victor), and Biovail (Dr Victor). This research was also supported in part by the Norman and Audrey Kaplan Chair in Hypertension at the University of

Texas Southwestern (Dr Victor), the Burns and Allen Chair

in Cardiology Research at the Cedars-Sinai Heart Institute (Dr Victor), and by a research grant from The Lincy

Foundation (Dr Victor). Support was also provided by a

Harold Amos Award from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Dr Ravenell).

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 171 (NO. 4), FEB 28, 2011

349

WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

©2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ by a Partners Healthcare System User on 06/24/2014

Role of the Sponsor: The sponsor had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation,

review, or approval of the manuscript.

Online-Only Material: Four eFigures and 4 eTables are

available at http://www.archinternmed.com.

Additional Contributions: Martin Shapiro, MD, provided helpful comments and suggestions during critical

revision of the manuscript. Julie Groth, MPH, and Edward Szczepaniak, PhD, provided administrative support revising the manuscript.

REFERENCES

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A Closer Look at African American

Men and High Blood Pressure Control: A Review of Psychosocial Factors and

Systems-Level Interventions. Atlanta, GA: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2010.

2. Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke

statistics—2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119

(3):480-486.

3. Cutler JA, Sorlie PD, Wolz M, Thom T, Fields LE, Roccella EJ. Trends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control rates in United States adults

between 1988-1994 and 1999-2004. Hypertension. 2008;52(5):818-827.

4. Victor RG, Leonard D, Hess P, et al. Factors associated with hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in Dallas County, Texas. Arch Intern Med. 2008;

168(12):1285-1293.

5. Connell P, Wolfe C, McKevitt C. Preventing stroke: a narrative review of community interventions for improving hypertension control in black adults. Health

Soc Care Community. 2008;16(2):165-187.

6. Kotchen JM, Shakoor-Abdullah B, Walker WE, Chelius TH, Hoffmann RG, Kotchen

TA. Hypertension control and access to medical care in the inner city. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(11):1696-1699.

7. Victor RG, Haley RW, Willett DL, et al; Dallas Heart Study Investigators. The Dallas Heart Study: a population-based probability sample for the multidisciplinary

study of ethnic differences in cardiovascular health. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93

(12):1473-1480.

8. Ferdinand KC. The Healthy Heart Community Prevention Project: a model for primary cardiovascular risk reduction in the African-American population. J Natl

Med Assoc. 1995;87(8)(suppl):638-641.

9. Ferdinand KC. Lessons learned from the Healthy Heart Community Prevention

Project in reaching the African American population. J Health Care Poor

Underserved. 1997;8(3):366-372.

10. Harris-Lacewell MV. Barbershops, Bibles, and BET; African Americans; Politics;

Government. Woodstock, England: Princeton University Press; 2006.

11. Hess PL, Reingold JS, Jones J, et al. Barbershops as hypertension detection, referral, and follow-up centers for black men. Hypertension. 2007;49(5):1040-1046.

12. Murphy M, Hansgen HC. Barbershop Talk: The Other Side of Black Men. Merrifield, VA: Melvin Murphy; 1998.

13. Project brotherhood. A black man’s clinic. http://projectbrotherhood.net/. Accessed April 14, 2010.

14. The Black Barbershop. The black barbershop health outreach program. http:

//www.blackbarbershop.org/PHOENIX.htm. Accessed April 14, 2010.

15. Chilenski D. Barbershop tour: redux. www.slu.edu/x35530.xml. Accessed April

14, 2010.

16. Mitka M. Efforts needed to foster participation of blacks in stroke studies. JAMA.

2004;291(11):1311-1312.

17. Shaya FT, Gu A, Saunders E. Addressing cardiovascular disparities through community interventions. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1):138-144.

18. Victor RG, Ravenell JE, Freeman A, et al. A barber-based intervention for hypertension in African American men: design of a group randomized trial. Am Heart

J. 2009;157(1):30-36.

19. Murray DM. Design and Analysis of Group Randomized Trials. New York, NY:

Oxford University Press Inc; 1998.

20. Murray DM, Varnell SP, Blitstein JL. Design and analysis of group-randomized

trials: a review of recent methodological developments. Am J Public Health. 2004;

94(3):423-432.

21. Campbell MK, Elbourne DR, Altman DG; CONSORT group. CONSORT statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 2004;328(7441):702-708.

22. CDC AIDS Community Demonstration Projects Research Group. Communitylevel HIV intervention in 5 cities: final outcome data from the CDC AIDS Community Demonstration Projects. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(3):336-345.

23. Parati G, Stergiou GS, Asmar R, et al. European Society of Hypertension Practice Guidelines for home blood pressure monitoring [published online June 3,

2010]. J Hum Hypertens. doi:10.1038/jhh.2010.54.

24. Pickering TG, Miller NH, Ogedegbe G, Krakoff LR, Artinian NT, Goff D; American

Heart Association; American Society of Hypertension; Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. Call to action on use and reimbursement for home blood

pressure monitoring: a joint scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American Society of Hypertension, and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses

Association. Hypertension. 2008;52(1):10-29.

25. Jones CR, Taylor K, Poston L, Shennan AH. Validation of the Welch Allyn “Vital

Signs” oscillometric blood pressure monitor. J Hum Hypertens. 2001;15(3):

191-195.

26. Department of Health and Human Services. Annual Update of the HHS Poverty

Guidelines. http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/07fedreg.pdf. Accessed September 8, 2010.

27. Hunink MG, Goldman L, Tosteson AN, et al. The recent decline in mortality from

coronary heart disease, 1980-1990: the effect of secular trends in risk factors

and treatment. JAMA. 1997;277(7):535-542.

28. Weinstein MC, Coxson PG, Williams LW, Pass TM, Stason WB, Goldman L.

Forecasting coronary heart disease incidence, mortality, and cost: the Coronary

Heart Disease Policy Model. Am J Public Health. 1987;77(11):1417-1426.

29. Bibbins-Domingo K, Chertow GM, Coxson PG, et al. Projected effect of dietary

salt reductions on future cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(7):

590-599.

30. Fraser M, Brown H, Homel P, et al. Barbers as lay health advocates--developing

a prostate cancer curriculum. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101(7):690-697.

31. Williams DR. The health of men: structured inequalities and opportunities. Am J

Public Health. 2008;98(9)(suppl):S150-S157.

32. Volpp KG, Troxel AB, Pauly MV, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of financial

incentives for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(7):699-709.

33. Fiscella K, Holt K. Racial disparity in hypertension control: tallying the death toll.

Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(6):497-502.

34. Rein DB, Constantine RT, Orenstein D, et al. A cost evaluation of the Georgia Stroke

and Heart Attack Prevention Program. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(1):A12.

35. Institute of Medicine. A Population-Based Policy and Systems Change Approach to Prevent and Control Hypertension. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010.

36. Brownstein JN, Chowdhury FM, Norris SL, et al. Effectiveness of community health

workers in the care of people with hypertension. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(5):

435-447.

37. Dobson J. Barber into surgeon. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1974;54(2):84-91.

INVITED COMMENTARY

ONLINE FIRST

A Bald Fade and a BP Check

A

s a black man with HTN who has frequented

the same community barber for 17 years, I

reviewed with great fascination the article by

Victor et al. I typically get a “bald fade” haircut, which

camouflages my frontal baldness, and sit quietly as the

barbers and other patrons address the burning issues

of the day. More importantly, the black barbershop

experience is a remarkable social barometer that pro-

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 171 (NO. 4), FEB 28, 2011

350

WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

©2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ by a Partners Healthcare System User on 06/24/2014