Miranda Pushed 'Voluntariness' to the Background

advertisement

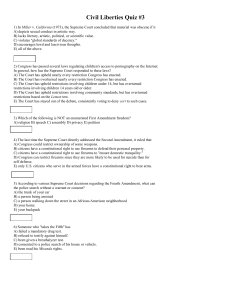

Volume 153, No. 99 18, May, 2007 Miranda Pushed 'Voluntariness' to the Background Recently the 2d District Appellate Court did something quite extraordinary: Within a span of a month, it found confessions in two different cases to be involuntary. People v. Kebron R. Dennis, No. 2-041161 (April 20), and People v. Josh L. Westmorland, No. 2-05-1093 (March 30). Why is this extraordinary? Because ''two'' is also the number of confessions the U.S. Supreme Court has held involuntary during the last 41 years. Why has it taken the U.S. Supreme Court four decades to do what the 2d District did in four weeks? To answer this, we need to go back to 1966 - the year the Supreme Court decided Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436. Before 1966, ''voluntariness'' was the test for determining the admissibility of confessions. This was the test established through common law. As far back as 1783, an English court held that ''no credit'' should be given to ''a confession forced from the mind by the flattery of hope, or by the torture of fear.'' Rex v. Warickshall, 168 Eng. Rep. 234, 235. The underlying value of the test was to prevent the admission of false confessions. Both state and federal courts in the 19th century generally adopted this test. In fact, the U.S. Supreme Court located the voluntariness test both within the Fifth Amendment's self-incrimination clause (Bram v. U.S., 168 U.S. 532 (1897)) as well as through its general supervisory power over federal court procedure (Hopt v. Utah, 110 U.S. 574 (1884)). But in 1936, the Supreme Court faced a conundrum in a case called Brown v. Mississippi, 297 U.S. 278. Brown concerned a confession admitted at a state criminal trial that was clearly obtained by torture. The problem was that in 1936 the self-incrimination clause was not binding on state courts. (This would not change until Malloy v. Hogan, 378 U.S. 1 (1964).) Avoiding a struthious posture, the court instead reversed the Mississippi state court decision by holding that the voluntariness test was also found in the 14th Amendment's due process clause. The Supreme Court has held that a statement is involuntary if ''the defendant's will has been 'overborne' or his 'capacity for self-determination critically impaired.' '' Schneckloth v. Bustamonte, 412 U.S. 218, 225 (1973). To make this determination, the court relies on a ''totality of circumstances'' test that includes both the subjective characteristics of the defendant as well as the objective details of how the police conducted the interrogation. Between 1936 and 1966, the court decided almost three dozen cases involving the issue of involuntary confessions. The 1966 Miranda decision resulted in a sea change in confession law. Miranda, of course, provided that police may not conduct a custodial interrogation of a suspect without first informing him of his rights and then obtaining a waiver. Thus, even a voluntary confession can be suppressed if the police violate the rules of Miranda. Miranda supplements - but does not supersede - the voluntariness test. In fact, for a criminal-defense lawyer the ''involuntariness'' argument is always preferred over Miranda. This is true because, while a statement produced through a Miranda violation cannot be used in the state's case-in-chief, the statement can still be used for impeachment. Harris v. New York, 401 U.S. 222 (1971). On the other hand, an involuntary statement cannot be used for any purpose at trial, including impeachment. Moreover, a voluntary statement obtained in violation of Miranda will not result in the suppression of physical fruits of the statement. U.S. v. Patane, 542 U.S. 630 (2004). On the other hand, physical fruits of an involuntary statement are suppressed. Curiously, since Miranda the U.S. Supreme Court has lost interest in deciding cases dealing with the issue of voluntariness. Since Miranda came down in 1966, the court has decided close to 80 cases construing the Miranda decision. Yet during this same period, the court has found only two statements to be involuntary. Arizona v. Fulminante, 499 U.S. 279 (1991); Mincey v. Arizona, 437 U.S. 385 (1978). Even worse, the court has erroneously suggested that as long as Miranda is followed the resulting statement will probably be voluntary. In one of the court's more mystifying statements, it has insisted that ''[C]ases in which a defendant can make a colorable argument that a self-incriminating statement was 'compelled' despite the fact that the law enforcement authorities adhered to the dictates of Miranda are rare.'' Dickerson v. U.S., 530 U.S. 428, 444 (2000), quoting Berkemer v. McCarty, 468 U.S. 420, 433 n.20 (1984). But there is no necessary relation between following Miranda and obtaining a voluntary statement. After all, it is just as easy to use physical force to obtain a confession with a Miranda waiver as without. So the Supreme Court's lack of interest in developing the ''voluntariness'' doctrine during the last 40 years is very troubling. And the Supreme Court's neglect of this area of the law makes any attention state courts provide even more significant. This is why the 2d District's two new cases deserve serious attention. In Dennis, the police suspected that the defendant was involved in an incident that resulted in the shooting of both Curtis Mitchell and the defendant, Kebron R. Dennis, himself. Officer Larry Holman confronted Dennis alone in a curtained-off area of a hospital emergency room. He observed that Dennis had a ''through and through'' bullet wound in his upper thigh. Despite this, the officer repeatedly asked him to reveal the location of the gun used in the shooting. When Dennis responded that he did not know, the officer repeated the question again and again. The officer testified that Dennis became visibly upset and began to cry. Further questions by the officer elicited incriminating answers. After 10 minutes, a nurse entered the room and asked the officer to leave so that Dennis could receive treatment. The 2d District held that Dennis' statements were involuntary. In reaching this conclusion, the court emphasized that the burden of proving that a statement is voluntary lies with the state. Here, the state introduced no evidence concerning Dennis' precise mental and physical condition at the time the officer questioned him in the emergency room. The officer did not know whether Dennis had received medical treatment or whether he had been medicated or whether he was in shock. The officer admitted that he spoke with no medical personnel concerning Dennis' condition. He conceded that Dennis' leg injury was bleeding and had not been bandaged during the interrogation. He also conceded that the defendant began to cry during the questioning. In light of all these circumstances, the court found that the state failed in its burden of proving that Dennis' statements were voluntary, and thus it suppressed them. The court then considered oral and written statements Dennis later made at the police station following Miranda warnings and a waiver of his rights. The court found insufficient evidence of attenuation, and thus also suppressed these later statements as fruit of the poisonous tree of the earlier involuntary hospital statements. While Dennis dealt with an adult defendant, the Westmorland case dealt with a minor who was 17 years old. Josh L. Westmorland was arrested at his home. The arresting officers neither inquired whether Westmorland's parents were home, nor made any effort to contact them. At the police station, Westmorland was read his Miranda rights and then signed a written waiver. At that point Westmorland asked to speak with his mother. The officer told him that he had no right to have his mother in the room with him during the interrogation. Westmorland then repeated his request and the officer made the same reply. A 90 minute interrogation ensued, and defendant made incriminating statements. The court found that the state failed to prove that the statements were voluntary by a preponderance of the evidence. The factor the court found most unsettling was the police officer's refusal of the defendant's two requests to talk with his mother. The Juvenile Court Act places an explicit duty on the police, before any interrogation of a juvenile, to locate a parent; the purpose of this requirement is to provide the juvenile with an opportunity to confer with a parent before interrogation. 705 ILCS 405/5-405 (2002). The court conceded that the Juvenile Act did not apply to Westmorland because he was 17. Yet the court looked to what it referred to as ''common-law/constitutional sources,'' rather than merely statutory authority, for the importance of what it referred to as the ''concerned adult factor.'' In doing so, the court noted the irony that the difference of one day - the day a person turns 17 would determine whether the statute mandates the help of an adult before interrogation. But grounding a minor's right to the help of a ''concerned adult'' on the ''common-law/constitutional sources'' recognizes the reality that ''teenagers do not mature in the span of a day.'' The court conceded that voluntariness is based on the ''totality of the circumstances'' and not merely the presence or absence of any one factor. Nevertheless, its review of Illinois case law led it to conclude that ''courts [in Illinois] place an emphasis on the 'concerned adult' factor where the police fail to honor a minor's request to speak to a parent before or during an interview or where the police are indifferent to or intentionally frustrate a parent's own efforts to contact the minor.'' It thus held the statements to be involuntary. (Westmorland's Miranda waiver was, of course, irrelevant to the finding of involuntariness.) Confession law in the U.S. Supreme Court has often been reduced to arcane Miranda issues. The court has ceded the hugely important area of voluntariness of confessions almost entirely to state courts. Criminal-defense attorneys should take note.