16

Chapter

Managers as Leaders

Leaders in organizations make things happen. But w hat makes leaders different

from nonleaders? W hat is the m ost appropriate style of leadership? W hat can you

do to be seen as a leader? Those are just a few of the questions w e will try to

answer in this chapter. Focus on the following learning outcomes as you read and

study this chapter.

LEARNING

OUTCOMES

386

6.1

Define leaders and leadership.

page 388

6.2

Describe historical leadership in the Arab world.

page 389

6.3

Compare and contrast early theories of leadership.

page 391

6.4

Describe the three major contingency theories of

leadership.

page 395

6.5

Describe contemporary views of leadership.

page 399

6.6

Discuss tw enty-first-century issues affecting

leadership.

page 401

Meet the Managers

M on a f3aw a rshi

CEO, Al-GezairiTransport, Beirut, Lebanon

WHAT IS YOUR JOB? Doing a lot o f m anagement o f people to enable

forw arding o f cargo to happen. I [handle] the logistics o f people w ho do

the logistics of cargo, packing, storage and transport.

WHAT IS THE BEST PART OF YOUR JOB? People.

WHAT IS THE WORST PART OF YOUR JOB? People.

WHAT IS THE BEST MANAGEMENT ADVICE YOU HAVE RECEIVED?

Listen to your gut feeling as a push forward in your decision.

Z o u h a ir Eloudghiri

CEO of Foods Sector, Savola Group, Saudi Arabia

WHAT IS YOUR JOB? Leading six edible oils business units across the Middle

East region, w ith six manufacturing plants, a turnover of US$1.5 billion, and profit

o f US$160 m illion.

WHAT IS THE BEST PART OF YOUR JOB? Coaching executives to innovate

fo r the consumer and optimize costs to deliver best value.

WHAT IS THE WORST PART OF YOUR JOB? Making the tough decisions

about non-perform ing executives w ho are asked to go find a better fit to

th e ir skills.

WHAT IS THE BEST MANAGEMENT ADVICE YOU HAVE RECEIVED? Hire the best, coach

them , and delegate the m axim um to them.

You will be hearing more from these real

managers throughout the chapter.

387

388

P a r t F o u r Leading

A Manager's

Dilemma

Leading by Example

HCL Technologies is headquartered in the w orld's largest dem ocracy, so it

is quite fitting that th e N e w Delhi-based co m p an y is attem pting a radical

experim ent in w orkplace dem ocracy.1 CEO Vineet N ayar is com m itted

to creating a co m p an y w h e re th e job of com pany

leaders is to enable people to find th eir ow n destiny

by gravitating to th eir strengths. A lthough he believes

th at th e com m and-and-control dictatorship approach

is the easiest m a n a g e m e n t style, he also thinks it is

not th e m ost productive. In his corporate dem ocracy,

em ployees can w rite a "tro u ble ticket" on anyone

in the com pany. A nyone w ith tro u ble tickets has

to respond, just as if he or she w ere dealing w ith

a custom er w h o had problem s and needed som e

response. N ayar also believes that leaders should

be open to criticism. He volunteered to share the

weaknesses fro m his 360-d eg ree feedback fo r all

em ployees to see. A lthough a lot of people said he w as

crazy to com m unicate his weaknesses, N ayar believed

th at it w as a good w a y to increase his accountability

as a leader to his em ployees. Such an en viron m ent

requires a lot o f trust betw een leaders and follow ers.

H o w can N ayar continue to build th at trust?

V in e et N a ya r is a good ex am p le of w h a t it takes to be a leader in today's

organizations. He has created an en viro n m e n t in w hich em plo yees feel like

th ey are heard and trusted. H o w ever, it is im p ortan t that he continues to

n urture this culture a n d be seen as an effective leader. W h y is leadership so

im portant? Because the leaders in organizations m ake things happen.

Im a g in e yo u w e re th e CEO in a w o rkp lace dem ocracy.

W h a t would you do?

LEARNING

o u t c o m e

1 6 .1

> W H O ARE LEADERS, AND W HAT IS LEADERSHIP?

Let’s begin by clarifying who leaders are and what leadership is. O ur definition o f

a leader is som eone who can influence others and who has managerial authority.

Leadership is what leaders do. It is the process o f leading a group and influencing that

group to achieve its goals.

Are all managers leaders? Because leading is one o f the four management func­

tions, ideally all managers should be leaders. Thus, we are going to study leaders and

leadership from a managerial perspective.2 However, even though we are looking at

these from a managerial perspective, we are aware that informal leaders often emerge

in groups. Although these informal leaders may be able to influence others, they have

n ot been the focus o f most leadership research and are n ot the types o f leaders we are

studying in this chapter.

Leaders and leadership, like m otivation, are organizational behavior topics

that have been researched a lot. M ost o f that research has been aim ed at answering

Chapter Sixteen M anagers as Leaders

389

the qu estion , “W hat is an effective lea d er?” We will b eg in ou r study o f leader­

ship by look in g at som e early leadership theories that attem pted to answer that

question.

QUICK LEARNING REVIEW:

L E A R N IN G O U T C O M E

•

1 6 .1

D efin e lea d e r and leadership.

•

Explain w h y m a n a g e rs should be leaders.

----------------------------------------------------------- Go to page 4 0 9 to see how well you know th is material.

LEARNING

o u t c o m e

1 6 .2

> HISTORICAL LEADERSHIP IN THE ARAB WORLD

IBN KHALDUN CONCEPTION OF LEADERSHIP

A cco rd in g to Islamic teachings, a leader is a person who has the attributes o f

honesty, com petence, inspiration, humility, patience, and seeks consultation from

others.3 They d o acknowledge that leaders who have all o f these attributes are rare,4

but this represents an ideal that leaders, in politics or in business, should strive

to achieve. Likewise, leading monks in Christian monasteries in M ount L ebanon

would undoubtedly require exceptional leaders.

Aside from the religious c o n ce p tio n o f leaders, leadership - as a social

phenom enon - has a long history in the Arab world. Ibn Khaldun was probably the

first to specify what leadership is and how it is form ed.5 Although he was mainly inter­

ested in political leadership, his conceptualization is im portant for understanding

leadership in any context, business or non-business, especially in this region o f the

world. Ibn Khaldun was born in Tunis in the year 1332. His life was characterized

by significant (although mostly not successful) political undertaking and intellectual

enterprise. After being imprisoned for two years, he secluded himself in a fortress and

started writing his version o f the history o f the world. H e finished his most important

book, the Muqaddimah (Prolegom ena or the Introduction), in the year 1377. In the

Muqaddimah, Ibn Khaldun emphasizes the personal qualities o f the leader. He calls

those qualities “perfecting details.” Such qualities include generosity, forgiveness o f

error, patience and perseverance, hospitality toward guests, maintenance o f the indi­

gent, patience in unpleasant situations, execution o f commitments, respect for the

religious law, reverence for old men and teachers, fairness, meekness, consideration

to the needs o f followers, adherence to the obligations o f religious laws, and avoidance

o f deception and fraud. G ood leadership, according to Ibn Khaldun, requires kind­

ness to, and protection of, subjects. He emphasizes the need o f the leader to be mild

to his followers and to gain their love. He notes, probably surprisingly, that a leader

should not be too shrewd. This is the case because such a quality would distance him

from his subjects.6

THE ROLE OF ASABIYA

Many leaders fail, in Ibn K haldun’s op in ion , because o f their inability to under­

stand the significance o f asabiya (”group feelin g ” or “group b o n d ”). Asabiya stems

from b lo o d ties and alliances, with the form er having the m ost weight in fostering

the leadership bond. While b lo o d ties may be discounted in the West as a source

o f leadership, o n e can only review recen t organizational history in the M iddle

East and N orth Africa to see how m uch b lo o d ties are instrumental in leadership

Leader

Leadership

A person w h o can influence others and w h o has

m anagerial authority.

A process o f influ encing a g ro u p to achieve goals.

390

P a r t F o u r Leading

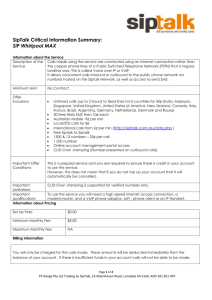

Exhibit 16-1

S ocial O rig in s

■

L e adership C lim a te

Khadra’s Model of

Leadership

Source: Bashir Khadra, 1990,

"The Prophetic-Caliphal Model

o f Leadership: An Empirical

S tu d y," In te rn a tion a l Studies o f

M a nagem ent & Organization,

20, (3), 37-51

Prophetic Model

Lack of

institutionalism

!

Individualism_|

Caliphal Model

em ergence. In recent M iddle Eastern societies, leadership em ergence is sometimes

greatly aided by descent. This is the case in political situations and also in business

organizations.

THE PROPHETIC-CALIPHAL MODEL OF LEADERSHIP

Addressing leadership in Arab contexts, several authors have noted the tribal con cep­

tion o f leadership that seems to typify many Arab organizations.7 The “sheikh” is not

necessarily the autocratic leader to whom everybody listens. O n the contrary, he is a

person who continuously seeks the advice o f his followers and interacts with them.

These interactions signify what is termed “shiekhocracy.”8

O n e o f the relevant models for leadership in Arab contexts is the one put forward

by Bashir Khadra, who proposed a prophetic-caliphal m odel o f leadership in the Arab

world (Exhibit 16 -1). This m odel consists o f four elements: (1) personalism, (2) indi­

vidualism, (3) lack o f institutionalization, and (4) the importance o f the great man.

Personalism, refers to the egocentric view that a person has in relation to others. It refers

to the degree that a person insists on his personal opinion and the degree o f concern

and emphasis he has on himself. Individualism means making decisions or actions that

do not take into account the opinions o f the group. The com bination o f personalism

and individualism leads to a lack o f institutional development. Leadership is thus more

vested in the person, rather than being vested in an institution. In cases o f conflict or

succession, there is n o institution to fill the vacuum. The vacuum is alternatively filled

by an expectation o f the “great m an.” If the expected great man really turns out to be

a great man, then we have a “prophetic” type o f leader whose relationship with follow­

ers depends on love and compassion and voluntary com pliance. If on the other hand,

the expected great man turns out to be an “ordinary m an” then the only way to ensure

follower com pliance is through coercion and authoritarianism.

QUICK LEARNING REVIEW:

L E A R N IN G O U T C O M E

•

•

1 6 .2

U n d ers tan d in g leadersh ip fro m an A rab perspective.

Describe th e concept o f asabiya.

•

Explain th e p ro ph etic-calip h al leadersh ip m o d el.

----------------------------------------------------------- Go to page 4 0 9 to see how well you know th is material.

Chapter Sixteen M anagers as Leaders

391

LEARNING

O UTCO M E

16.3 > EARLY LEADERSHIPTHEORIES

P eople have b een interested in leadership since they started com in g together in

groups to accom plish goals. The twentieth century witnessed a growing interest in

the study o f leadership. These early leadership theories focused on the leader (trait

theories) and how the leader interacted with his or her group members (behavioral

theories).

TRAIT THEORIES

Jamal A bdel Nasser was Prime Minister and then President o f Egypt from 1954 to

1970. During his lifetime, his leadership qualities earned him many dedicated followers.

Those who adm ired him believed that his magnetism, confidence, ability to com m uni­

cate, and “presence” made him a great leader. The trait theories o f leadership would

consider his leadership by focusing on these traits.

Leadership research in the 1920s and 1930s focu sed on isolating leader traits,

that is, characteristics that would differentiate leaders from nonleaders. Som e o f the

traits studied included physical stature, appearance, social class, em otional stability,

fluency o f speech, and sociability. Despite the best efforts o f researchers, it proved

impossible to identify a set o f traits that would always differentiate a leader (the person)

from a nonleader. Maybe it was a bit optimistic to think that there could be consis­

tent and unique traits that would apply universally to all effective leaders, n o mat­

ter whether they were in charge o f Toyota M otor C orporation, O rascom Telecom

in Egypt, the King Abdullah E conom ic City in Saudi Arabia, the emirate o f Dubai, a

local sports club, or Cairo University. However, later attempts to identify traits consis­

tently associated with leadership (the process, n ot the person) were m ore successful.

T he seven traits shown to be associated with effective leadership are described briefly

in Exhibit 16-2.9

Researchers eventually recognized that traits alone were not sufficient for identi­

fying effective leaders because explanations based solely on traits ignored the inter­

actions o f leaders and their group members as well as situational factors. Possessing

the appropriate traits only made it m ore likely that an individual would be an effec­

tive leader. T h erefore, leadership research from the late 1940s to the mid-1960s

Exhibit 16-2

Seven Traits Associated

with Leadership

1. D rive. Leaders exhibit a high effort level. They have a relatively high desire for achievement,

they are ambitious, they have a lot of energy, they are tirelessly persistent in their activities,

and they show initiative.

2. Desire to lead. Leaders have a strong desire to influence and lead others. They demonstrate

the willingness to take responsibility.

3. H o n e s ty a n d in te g rity . Leaders build trusting relationships w ith followers by being truthful

or nondeceitful and by showing high consistency between w ord and deed.

4. S elf-co nfid en ce. Followers look to leaders for an absence of self-doubt. Leaders, therefore,

need to show self-confidence in order to convince followers of the rightness of their goals

and decisions.

5. In te llig e n c e . Leaders need to be intelligent enough to gather, synthesize, and interpret

large amounts of inform ation, and they need to be able to create visions, solve problems,

and make correct decisions.

6. J o b -re le v a n t kn o w le d g e . Effective leaders have a high degree of knowledge about the

com pany, industry, and technical matters. In-depth know ledge allows leaders to make

w ell-inform ed decisions and to understand the implications of those decisions.

7. E xtra ve rsio n . Leaders are energetic, lively people. They are sociable, assertive, and rarely

silent or w ithdraw n.

Sources: S. A. Kirkpatrick and E. A. Locke, "Leadership: Do Traits Really M atter?" A ca d em y o f M a na g e m en t Executive, May

1991, pp. 48-60; and T A. Judge, J. E. Bono, R. Ilies, and M. W. G erhardt, "P erso n a lity and Leadership: A Q u alititative

and Q uantitative R eview " J o urn a l o f A p p lie d Psychology, A ugust 2002, pp. 765-780.

392

P a r t F o u r Leading

concentrated on the preferred behavioral styles that leaders demonstrated. Researchers

w ondered whether there was something unique in what effective leaders did - in other

words, in their behavior.

BEHAVIOR THEORIES

Mutasim Mahmassani is the general m anager o f Al Baraka Bank in L ebanon. H e

is an ardent believer in teamwork, arguing that “ [t]h e institution cann ot survive

o n individual efforts but collective ones, p rov id ed individual achievem ents are

prop erly re co g n iz e d .”10 Mahmassani encourages em ployees’ participation, h elp ­

ing them realize their full potential. His on-the-job behavior mim ics his beliefs:

he is considerate, pleasant, and friendly, while n ot com prom ising on effectiveness.

Contrast this style with the style o f another m anager described as “blunt, sarcastic,

tactless, and tou g h .” W hat would the im pact be on the followers o f each o f these

two leaders?

Researchers h op ed that the behavioral theories approach would provide m ore

definitive answers about the nature o f leadership than the trait theories. The four

main leader behavior studies are summarized in Exhibit 16-3.

U niversity of Io w a studies. The University o f Iowa Studies, con d u cted in the United

States, explored three leadership styles to find which was the m ost effective.11 The

autocratic style described a leader who dictated work m ethods, m ade unilateral

decisions, and lim ited em ployee participation. T he democratic style described a

Exhibit 16-3

Behavioral Theories

of Leadership

University of lowa

Behavioral Dimension

Conclusion

D e m o cra tic style : involving

subordinates, delegating

authority, and encouraging

participation

Democratic style of leadership

was most effective, although

later studies showed mixed

results.

A u to c ra tic sty le : dictating work

methods, centralizing decision

making, and limiting

participation

Laissez-faire sty le : giving group

freedom to make decisions

and com plete w ork

Ohio State

C o n sid e ra tio n : being

considerate of followers'

ideas and feelings

In itia tin g s tru c tu re : structuring

w ork and w ork relationships

to meet job goals

University of Michigan

E m p lo y e e o rie n te d : em phasized

interpersonal relationships

and taking care of em ployees'

needs

High-high leader (high in

consideration and high in

initiating structure) achieved

high subordinate perform ance

and satisfaction, but not in all

situations

Em ployee-oriented leaders

w ere associated w ith high

group productivity and

higher job satisfaction.

P ro d u ctio n o rie n te d : emphasized

technical or task aspects of job

Managerial Grid

Concern fo r p e o p le : measured

leader's concern for

subordinates on a scale

of 1 to 9 (low to high)

Concern fo r p ro d u c tio n :

measured leader's concern

for getting job done on a

scale 1 to 9 (low to high)

Leaders perform ed best with

a 9.9 style (high concern for

production and high concern

for people).

Chapter Sixteen M anagers as Leaders

Meet the Managers

W HAT TRAITS SHOULD

LEADERS HAVE?

They should be do-ers,

not procrastinators.

Leadership is

action, not

a position.

Leaders should have Integrity,

intelligence, energy, and

em powerment.

393

leader who involved em ployees in decision making, delegated authority, and used

feedba ck as an opportunity fo r coach ing employees. Finally, the laissez-faire style

described a leader w ho let the grou p make decisions and com p lete the work in

whatever way it saw fit. The researchers’ results seem ed to indicate that the d em o­

cratic style contributed to both g o o d quantity and quality o f work. H ad the answer

to the question o f the m ost effective leadership style been fou n d? Unfortunately,

it was n ot that simple. Later studies o f the autocratic and dem ocratic style showed

m ixed results. For instance, the dem ocratic style sometimes p rod u ced higher per­

form an ce levels than the autocratic style, but at other times, it did not. However,

m ore consistent results were fou n d when a measure o f em ployee satisfaction was

used. G roup m em bers were m ore satisfied under a dem ocratic leader than under

an autocratic o n e .12

Now leaders had a dilemma! Should they focus on achieving higher perform ance

or on achieving higher m em ber satisfaction? This recognition o f the dual nature o f a

leader’s behavior, that is, the need to focus on the task and also focus on the people,

was a key factor in other behavioral studies, too.

The Ohio State studies. The O h io State University studies, also conducted in the United

States, identified two im portant dimensions o f leader behavior.13 Beginning with a

list o f m ore than 1,000 behavioral dimensions, the researchers eventually narrowed

it down to just two that accounted for most o f the leadership behavior described by

group members. The first dimension, called initiating structure, referred to the extent

to which a leader defined his or her role, and the roles o f group members, in attain­

ing goals. It included behaviors that involved attempts to organize work, work rela­

tionships, and goals. The second dimension, called consideration, was defined as the

extent to which a leader had work relationships characterized by mutual trust and

respect for group mem bers’ ideas and feelings. A leader who was high in consideration

helped group members with personal problems, was friendly and approachable, and

treated all group members as equals. He or she showed concern for (was considerate

of) his or her followers’ com fort, well-being, status, and satisfaction. Research found

that a leader who was high in both initiating structure and consideration (a high-high

leader) sometimes achieved high group task perform ance and high group m em ber

satisfaction, but n ot always.

University of M ichigan studies. Leadership studies conducted in the United States at the

University o f Michigan, at about the same time as those being done at O hio State, also

h oped to identify behavioral characteristic o f leaders that were related to perform ance

effectiveness. The Michigan group also came up with two dimensions o f leadership

behavior, which they labeled employee oriented and production oriented}4 Leaders who

were em ployee oriented were described as emphasizing interpersonal relationships.

T he production-oriented leaders, in contrast, tended to emphasize the task aspects

o f the jo b . Unlike the other studies, the Michigan studies concluded that leaders who

were em ployee oriented were able to get high group productivity and high group

m em ber satisfaction.

B ehavioral th eo ries

D em ocratic style

In itia tin g structure

Leadership theories th a t id e n tify behaviors th a t

d iffe re n tia te effective leaders from ineffective leaders.

A leader w h o involves em ployees in decision m aking,

delegates au th ority, and uses feed back as an o p p o rtu n ity

fo r co aching em ployees.

The exte nt to w h ich a leader defines his or her role

and the roles o f g ro u p m em bers in a tta in in g goals.

A u to cra tic style

A leader w h o dictates w o rk m ethods, makes unilateral

decisions, and lim its em ployee pa rticip a tio n .

Laissez-faire style

A leader w h o lets the group m ake decisions and

co m p le te the w o rk in w h a te v e r w a y it sees fit.

C onsideration

The exte nt to w h ich a leader has w o rk relationships

characterized by m utual tru s t and respect fo r group

m em bers' ideas and feelings.

H igh-high le ad e r

A leader high in bo th in itia tin g structure

and consideration behaviors.

394

P a r t F o u r Leading

Exhibit 16-4

The Managerial Grid

Country Club

Management

Team

Management

T h o u g h tfu l a tte n tio n

to needs o f p e o ple fo r

s a tis fy in g re la tio n s h ip

leads to a c o m fo rta b le ,

frie n d ly o rg a n iza tio n

a tm o s p h e re and

w o rk te m p o .

High

9

W o rk a cco m p lish e d

is fro m c o m m itte d p eople;

in te rd e p e n d e n ce th ro u g h

a "c o m m o n stake" in

o rg a n iza tio n p u rp o se

leads to re la tio n s h ip s

o f tru s t and respect.

9,9

1,9

8

7

Middle-of-the-Road

Management

6

A d e q u a te o rg a n iz a tio n

p e rfo rm a n c e is p o ssib le

th ro u g h b a la n cin g th e

n e ce ssity to g e t o u t

w o rk w ith m a in ta in in g

m o ra le o f p e o ple at a

s a tis fa c to ry level.

5,5

5

4

3

2

Low

1

9,1

1,1

Task

Management

Impoverished

Management

E xe rtio n o f m in im u m

e ffo rt to g e t req u ire d

w o rk d o n e is

a p p ro p ria te to

su sta in o rg a n iza tio n

m e m b e rsh ip .

Concern for Production

Low

High

E fficie n cy in o p e ra tio n s

resu lts fro m a rra n g in g

c o n d itio n s o f w o rk in such

a w a y th a t h u m a n e le m e n ts

in te rfe re to a m in im u m

degree.

Sources: reprinted by perm ission o f H arvard Business Review. An e xh ib it fro m "B reakthrough in Organization D evelopm ent" by the

President and Fellows o f Harvard College. A ll rights reserved.

The M anagerial Grid. The behavioral dimensions from the early leadership studies pro­

vided the basis for the developm ent o f a two-dimensional grid for appraising leadership

styles. The managerial grid used the behavioral dimensions “concern for peop le” and

“concern for production” and evaluated a leader’s use o f these behaviors, ranking them

on a scale from 1 (low) to 9 (h igh ).15 Although the grid (shown in Exhibit 16-4) had

81 potential categories into which a leader’s behavioral style might fall, only five styles

were named: impoverished management (1,1), task management (9,1), middle-of-theroad management (5,5), country club management (1,9), and team management (9,9).

O f these five styles, the researchers concluded that managers perform ed best when

using a 9,9 style. Unfortunately, the grid offered n o explanations about what made a

manger an effective leader; it only provided a framework for conceptualizing leader­

ship style. In fact, there is little substantive evidence to support the conclusion that a 9,9

style is most effective in all situations.16

Leadership researchers were discovering that predicating leadership success

involved som ething m ore com plex than isolating a few leader traits or preferable

behaviors. They began looking at situational influences. Specifically, which leader­

ship styles m ight be suitable in different situations, and what were these different

situations?

Chapter Sixteen M anagers as Leaders

395

QUICK LEARNING REVIEW:

L E A R N IN G O U T C O M E

•

•

1 6 .3

Discuss w h a t research has show n ab o ut

lead ersh ip traits.

Contrast th e fin d in g o f th e fo u r b eh avio ral leadersh ip

th eo ries.

•

Explain th e dual n atu re o f a leader's behavior.

------------------------------------------------------------ Go to page 410 to see how well you know th is material.

LEARNING

o u t c o m e

1 6 .4

> CONTINGENCY THEORIES OF LEADERSHIP

“The corporate world is filled with stories o f leaders who failed to achieve greatness

because they failed to understand the context they were working in.”17 In this section,

we examine three contingency theories: the Fiedler model, Hersey and Blanchard’s situ­

ational leadership theory, and path-goal theory. Each o f these theories looks at defining

leadership style and the situation, and it attempts to answer the if-then contingencies

(that is, if this is the context or situation, then this is the best leadership style to use).

THE FIEDLER MODEL

The first com prehensive contingency m odel for leadership was developed by Fred

Fiedler.18 The Fiedler contingency model proposed that effective group perform ance

depended on properly matching the leader’s style and the am ount o f control and

influence in the situation. The m odel was based on the premise that a certain lead­

ership style would be m ost effective in different types o f situations. The keys were

to (1) define those leadership styles and the different types o f situations and then

(2) identify the appropriate combinations o f style and situation.

Fiedler proposed that a key factor in leadership success was an individual’s basic

leadership style, either task oriented or relationship oriented. Fiedler assumed that a

person’s leadership style was fixed, regardless o f the situation. In other words, if you

were a relationship-oriented leader, you would always be one, and if you were a taskoriented leader, you would always be one.

Fiedler’s research uncovered three contingency dimensions that defined the key

situational factors in leader effectiveness:

• Leader-member relations: the degree o f confidence, trust, and respect employees

had for their leader, rated as either g o od or poor.

• Task structure: the degree to which jo b assignments were formalized and structured,

rated as either high or low.

• Position power: The degree o f influence a leader had over activities such as hiring,

firing, discipline, prom otions, and salary increases, rated as either strong or weak.

Each leadership situation was evaluated in terms o f these three contingency vari­

ables, which when com bined produced eight possible situations that were either favor­

able or unfavorable for the leader (see the bottom o f Exhibit 16-5). Situations I, II,

and III were classified as highly favorable for the leader. Situations IV, V, and VI were

moderately favorable for the leader. A nd situations VII and VIII were described as

highly unfavorable for the leader.

O nce Fiedler had described the leader variables and the situational variables, he

had everything he needed to define the specific contingencies for leadership effec­

tiveness. He concluded that task-oriented leaders perform ed better in very favorable

M a n ag erial grid

Fiedler contingency m odel

A tw o -d im e n sio n a l grid fo r appraising leadership styles.

A leadership theo ry th a t proposed th a t effective group

perform ance depended on th e proper m atch betw een

a leader's style and th e degree to w h ich th e situ a tio n

allo w e d th e leader to co ntrol and influence.

396

P a r t F o u r Leading

Exhibit 16—5

The Fiedler Model

Task

Oriented

Relationship

Oriented

S itu a tio n F avorableness:

H ig h ly F avorable

M od e ra te

H ig h ly U n fa vo ra b le

*

Category

Leader-Member

Relations

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

G ood

G ood

G ood

G ood

Poor

Poor

Poor

Poor

Task Structure

High

High

Low

Lo w

High

High

Low

Low

Position Power

S tro n g

W eak

S tro n g

W eak

S tro n g

W eak

S tro n g

W eak

situations and in very unfavorable situations. (See the top o f Exhibit 16-5, where per­

form ance is shown on the vertical axis and situation favorableness is shown on the

horizontal axis). O n the other hand, relationship-oriented leaders perform ed better

in moderately favorable situations.

Because Fiedler treated an individual’s leadership style as fixed, there were only two

ways to improve leader effectiveness. First, you could bring in a new leader whose style

better fits the situation. For instance, if the group situation was highly unfavorable but

was led by a relationship-oriented leader, the group’s perform ance could be improved by

replacing that person with a task-oriented leader. The second alternative was to change

the situation to fit the leader. This could be done by restructuring tasks, by increasing or

decreasing the power that the leader had over factors such as salary increases, prom o­

tions, and disciplinary actions, or by improving the leader-member relations.

Research testing the overall validity o f Fiedler’s m odel has shown considerable

evidence in support o f the m odel.19 However, his theory was n ot without criticisms.

The m ajor criticism is that it is probably unrealistic to assume that a person cannot

change his or her leadership style to fit the situation. Effective leaders can, and do,

change their styles. Finally, the situation variables were difficult to assess.20 Despite

its shortcomings, the Fiedler m odel showed that effective leadership style needed to

reflect situational factors.

HERSEY AND BLANCHARD'S SITUATIONAL LEADERSHIP THEORY

Paul Hersey and Ken Blanchard developed a leadership theory that has gained a

strong follow ing am ong m anagem ent developm ent specialists.21 This m odel, called

Situational Leadership Theory (SLT), is a contingency theory that focuses on followers’

readiness. Before we proceed, there are two points we need to clarify: why a leadership

theory focuses on the followers and what is meant by the term readiness.

The emphasis on the followers in leadership effectiveness reflects the reality that

it is the followers who accept or reject the leader. Regardless o f what the leader does,

the g ro u p ’s effectiveness depends on the actions o f the followers. This is an im por­

tant dim ension that most leadership theories have overlooked or underemphasized.

Readiness, as defined by Hersey and Blanchard, refers to the extent to which people

have the ability and willingness to accom plish a specific task.

Chapter Sixteen M anagers as Leaders

397

SLT uses the same two leadership dimensions that Fiedler identified: task and rela­

tionship behavior. However, Hersey and Blanchard go a step further by considering each

as either high or low and then combining them into four specific leadership styles:

• Telling (high task-low relationship): The leader defines roles and tells peop le what,

how, when, and where to do various tasks.

• Selling (high task-high relationship): The leader provides both directive and sup­

portive behavior.

• Participating (low task-high relationship): The leader and the followers share in

decision making, the main role o f the leader is facilitating and communicating.

• Delegating (low task-low relationship): The leader provides little direction or support.

The final com pon en t in the SLT m odel is the four stages o f follower readiness:

• R1— People are both unable and unwilling to take responsibility for doing som e­

thing. Followers are n ot com petent or confident.

• R2— People are unable but willing to do the necessary jo b tasks. Followers are m oti­

vated but lack the appropriate skills.

• R3— People are able but unwilling to d o what the leader wants. Followers are com ­

petent but d o not want to d o something.

• R4— People are both able and willing to d o what is asked o f them.

SLT essentially views the lea d er-follow er relationship as like that o f a parent

and a child. Just as a parent needs to relinquish con trol when a child becom es m ore

mature and responsible, so, too, should leaders. As followers reach higher levels o f

readiness, the leader responds n ot only by decreasing control over their activities

but also by decreasing relationship behaviors. The SLT says if follow ers are at R1

(unable and unwilling to d o a task), the leader needs to use the telling style and give

clear and specific directions. If followers are at R2 (unable and willing), the leader

needs to use the selling style and display high task orientation to com pensate for

the follow ers’ lack o f ability, and high relationship orientation to get followers to

“buy in to” the leaders desires. If followers are at R3 (able and unwilling), the leader

needs to use the participating style to gain their support, and if em ployees are at R4

(both able and willing), the leader does n ot need to d o m uch and should use the

delegating style.

SLT has intuitive appeal. It acknow ledges the im p ortan ce o f follow ers and

builds on the logic that leaders can com pensate fo r ability and motivational limita­

tions in their followers. However, research efforts to test and support the theory

have generally been disappointing.22 Possible explanations include internal in con ­

sistencies in the m od el as well as problem s with research m ethodology. Despite its

appeal and wide popularity, we have to be cautious about any enthusiastic endorse­

ments o f SLT.

PATH-GOAL THEORY

Currently, one o f the most respected approaches to understanding leadership is pathgoal theory, which states that the leader’s jo b is to assist followers in attaining their

goals and to provide direction or support to ensure that their goals are compatible

with the goals o f the group or organization. D eveloped by Robert House, path-goal

theory takes key elements from the expectancy theory o f m otivation.23 The term

L e a d e r-m e m b e r relations

S itu a tio n a l leadership th e o ry (SLT)

P a th -g o a lth e o r y

One o f Fiedler's situ a tio n a l contingencies th a t described

th e degree o f confidence, trust, and respect em ployees

had fo r th e ir leader.

A leadership co ntin gency th e o ry th a t focuses

on fo llo w e rs ' readiness.

A leadership th e o ry th a t says the leader's jo b is to assist

fo llo w e rs in a tta in in g th e ir goals and to provide dire ctio n

or su pport needed to ensure th a t th e ir goals are

co m p a tib le w ith th e goals o f th e g ro u p o r organ izatio n.

Readiness

The exte nt to w h ich people have th e a b ility and

w illin g n e ss to accom plish a specific task.

398

P a r t F o u r Leading

path-goal is derived from the belief that effective leaders clarify the path to help their

followers get from where they are to the achievement o f their work goals, and make

the jou rn ey along the path easier by reducing roadblocks and pitfalls.

House identified four leadership behaviors:

• Directive leader: The leader lets subordinates know what is expected o f them, sched­

ules work to be done, and gives specific guidance on how to accom plish tasks.

• Supportive leader: The leader shows con cern fo r the needs o f follow ers and is

friendly.

• Participative leader: The leader consults with group members and uses their sugges­

tions before making a decision.

• Achievement-oriented leader: The leader sets challenging goals and expects followers

to perform at their highest level.

In contrast to Fiedler’s view that a leader could n ot change his or her behavior,

H ouse assumed that leaders are flexible and can display any or all o f these leadership

styles depending on the situation (Exhibit 16-6).

As Exhibit 16-6 illustrates, path-goal theory proposes two situational or contin­

gency variables that m oderate the leadership behavior-outcom e relationship: those

in the environm ent that are outside the control o f the follower (factors including task

structure, form al authority system, and the work group) and those that are part o f

the personal characteristics o f the follow er (including locus o f control, experience,

and perceived ability). Environmental factors determine the type o f leader behavior

required if subordinate outcom es are to be maximized; personal characteristics o f the

follow er determine how the environm ent and leader behavior are interpreted. The

theory proposes that a leader’s behavior will n ot be effective if it is redundant with

what the environmental structure is providing, or is incongruent with follow er char­

acteristics. For example, the following are some predictions from path-goal theory:

• Directive leadership leads to greater satisfaction when tasks are ambiguous or stress­

ful than when they are highly structured and well laid out. The followers are not

sure what to do, so the leader needs to give them some direction.

• Supportive leadership results in high employee perform ance and satisfaction when

subordinates are perform ing structured tasks. In this situation, the leader only needs

to support followers, not tell them what to do.

Exhibit 16-6

Path—Goal Model

Chapter Sixteen M anagers as Leaders

399

• Directive leadership is likely to be perceived as redundant am ong subordinates with

high perceived ability or with considerable experience. These followers are quite

capable, so they do n ot need a leader to tell them what to do.

• The clearer and m ore bureaucratic the form al authority relationships, the m ore

leaders should exhibit supportive behavior and de-emphasize directive behavior.

The organizational situation has provided the structure as far as what is expected o f

followers, so the leader’s role is simply to support.

• Directive leadership will foster higher em ployee satisfaction when there is substan­

tive conflict within a work group. In this situation, the followers need a leader who

will take charge.

• Subordinates with an internal locus o f control will be m ore satisfied with a participa­

tive style. Because these followers believe that they control what happens to them,

they prefer to participate in decisions.

• Subordinates with an external locus o f control will be m ore satisfied with a directive

style. These followers believe that what happens to them is a result o f the external

environment, so they would prefer a leader who tells them what to do.

• Achievement-oriented leadership will increase subordinates’ expectations that effort

will lead to high perform ance when tasks are ambiguously structured. By setting

challenging goals, followers know what the expectations are.

Research on the path-goal m odel is generally encouraging. A lthough n ot every

study has fou n d support fo r the m odel, the majority o f the evidence supports the

logic underlying the theory.24 In summary, an em ployee’s perform ance and satisfac­

tion are likely to be positively influenced when a leader chooses a leadership style that

compensates for shortcomings in either the employee or the work setting. However, if

a leader spends time explaining tasks that are already clear or when an employee has

the ability and experience to handle tasks without interference, the employee is likely

to see such directive behavior as redundant or even insulting.

QUICK LEARNING REVIEW:

L E A R N IN G O U T C O M E

•

•

1 6 .4

Explain Fiedler's co n tin g en cy m o d el o f leadersh ip.

D escribe situational leadersh ip theory.

•

Discuss h o w p a th -g o a l th e o ry explain s leadersh ip.

------------------------------------------------------------- Go to page 410 to see how well you know th is material.

LEARNING

o u t c o m e s

1 6 .5

> CONTEMPORARY VIEWS OF LEADERSHIP

What are the latest views o f leadership? There are two we want to look at: transforma­

tional-transactional leadership and team leadership.

TRANSFORMATIONAL-TRANSACTIONAL LEADERSHIP

Many early leadership theories viewed leaders as transactional leaders, that is, lead­

ers w ho led prim arily by using social exchanges (or transactions). Transactional

leaders guide or motivate followers to work toward established goals by exchanging

Task structure

Transactional leaders

One o f Fiedler's situ a tio n a l contingencies th a t described

th e degree to w h ich jo b assignm ents w e re form a lized

and structured.

Leaders w h o lead p rim a rily by using social

exchanges (o r transactions).

400

P a r t F o u r Leading

"I w ant to create som ething interesting

and n o t be re p e titive ," says Esam Janahi.

.As chairm an o f G u lf Finance House (GFH),

an Islam ic investm ent bank, Janahi plays a

key role in one o f the reg io n's m o st p o w e rfu l

establishm ents. His leadership seem s to

be innate. "I started to lo o k at things in a

diffe re n t w ay to o th e rs," he says. "O thers

w ill tell you, 'it can't happen, it w o n 't happen,

it's too d iffic u lt'. . . " Janahi is the type o f

leader w ho is alw ays on the lo oko ut fo r new

opportunities, n o t hesitating to take risks

where necessary. 26

Meet the Managers

W HAT MAKES A GOOD BUSINESS

LEADER?

A person w h o balances

long- and short-term

stakeholder needs

w hile delivering

sustainable

value to all.

Someone w ith a

vision of the future

and an insight

into people.

rewards fo r their productivity.25 But there is another type o f leader, a transforma­

tional leader, who stimulates and inspires (transforms) followers to achieve extraor­

dinary outcom es. Transformational leaders are charismatic leaders. A charismatic

leader is an enthusiastic and self-confident leader whose personality and actions influ­

ence p eop le to behave in certain ways. But transformational leadership goes beyond

ju st bein g charismatic. Transform ational leaders are perceived by their followers

to be inspirational, with the ability to intellectually stimulate them. C ontem porary

business examples in the Arab world would include Esam Janahi, chairman, o f Gulf

Finance H ouse, on e o f the m ost successful and innovative Islamic investment banks

in the M iddle East. Such leaders pay attention to the concerns and developm ental

needs o f individual followers: they help followers look at old problem s in new ways,

and they are able to excite, arouse, and inspire follow ers to exert extra effort to

achieve group goals.

Transactional and transformational leadership should not be viewed as opposing

approaches to getting things d on e.27 Transformational leadership develops from trans­

actional leadership. Transformational leadership produces levels o f em ployee effort

and perform an ce that go beyond what would occu r with a transactional approach

alone. Moreover, transformational leadership is m ore than charisma because a trans­

formational leader attempts to instill in followers the ability to question n ot only estab­

lished views but views held by the leader.28

T he evidence supporting the superiority o f transform ational leadership over

transactional leadership is overw helm ingly impressive. For instance, studies that

lo o k e d at m anagers in d ifferen t settings, in W estern con texts and also in the

Arab w orld, fo u n d that transform ational leaders were evaluated as m ore effective,

h igher perform ers, m ore prom otab le than their transactional counterparts, and

m ore interpersonally sensitive.29 In addition, evidence indicates that transforma­

tional leadership is strongly correlated with lower turnover rates and higher levels

o f productivity, em p loyee satisfaction, creativity, goal attainm ent, and follow er

well-being.

In a study assessing the form ation and developm ent o f Jordan ’s King Hussein

Cancer Center (KHCC), one o f the top cancer centers in the Middle East researchers

have attributed the success o f this center to transformational leadership. Leaders used

the four pillars o f transformational leadership to revamp this entity from an impover­

ished and “ineffectual care institution”30 into a world-class comprehensive care center.

The four pillars - inspirational motivation, idealized influence, individualized consid­

eration, and intellectual stimulation - contributed to the success and had an impres­

sive im pact on workers and stakeholders.

Chapter Sixteen M anagers as Leaders

401

Team Leadership. Because leadership is increasingly taking place within a team context

and m ore organizations are using work teams, the role o f the leader in guiding team

m embers has becom e increasingly important.

Many leaders are n ot equipped to handle the change to employee teams. As one

consultant noted, “Even the m ost capable managers have trouble making the tran­

sition because all the com m and-and-control type things they were encou raged to

d o before are n o longer appropriate. T h ere’s n o reason to have any skill or sense

o f this.”31 This same consultant estimated that 15 percent o f managers are natural

team leaders. A nother 15 percent could never lead a team because it runs counter to

their personality; that is, they are unable to sublimate their dominating style for the

g o o d o f the team. Then there is a group in the middle: team leadership does not com e

naturally to them, but they can learn it.

T h e ch a llen g e fo r m any m anagers is learn in g h ow to b e c o m e an effective

team leader. T h ey have lea rn ed skills such as sharing in fo rm a tio n patiently,

b e in g able to trust others and give up authority, and u n d erstan d in g w hen to

intervene. A n d effective team leaders have m astered the difficu lt balancing act

o f know ing w hen to leave their teams alon e and when to get involved. New team

leaders may try to retain to o m u ch co n tro l at a time when team m em bers n eed

m ore autonom y, or they may aban d on their teams at times w hen the teams n eed

su p port and h e lp .32

QUICK LEARNING REVIEW:

L E A R N IN G O U T C O M E

•

1 6 .5

D ifferen tia te b etw ee n transactio n al and

tra n s fo rm a tio n a l leadership.

•

Describe w h a t te a m leadersh ip involves.

------------------------------------------------------------- Go to page 410 to see how well you know th is material.

LEARNING

o u t c o m e s

1 6 .6

> LEADERSHIP ISSUES IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

It is not easy being a chief executive officer (CEO) today. This person, who is responsi­

ble for managing a company, faces a lot o f external and internal challenges, especially

when that person is a woman. M ona Bawarshi, CEO o f a Lebanese shipping company,

Al-Gezairi Transport Company, which does business all over the Middle East, is con ­

stantly dealing with such challenges. If anything goes wrong, she is the person held

responsible.

For most leaders, leading effectively in today’s environment is unlikely to involve

the challenging circumstances Bawarshi faces. However, twenty-first-century lead­

ers do deal with some important leadership issues. In this section, we look at some

o f these issues: managing power, developing trust, em powering employees, leading

across cultures, understanding gender differences in leadership, and becom ing an

effective leader.

MANAGING POWER

W here d o leaders get their power; that is, their capacity to influence work actions

or decisions? Five sources o f leader power have been identified: legitimate, coercive,

reward, expert, and referent.33

Tran sform atio nal leaders

C harism atic leaders

Leaders w h o stim u la te and inspire (transform ) fo llo w e rs

to achieve extraordinary outcom es.

Enthusiastic, se lf-c o n fid e n t leaders w ho se personalities

and actions influence people to behave in certain ways.

402

P a r t F o u r Leading

M ona Baw arshi heads A l-G ezairiTransport Company.

The o n ly daughter o f a successful entrepreneur, she faced

lo ts o f challenges in her career. M o st o f these are com m on

to any businessperson, male o r female. Being female ju s t

adds to the com plexity. Twenty-first-century leaders have

to deal w ith im p o rta n t issues such as m anaging power,

developing trust, em pow ering employees, leading across

cultures, understanding gender differences in leadership,

and becom ing an effective leader.

Legitimate power and authority are the same. Legitimate power represents the

pow er a leader has as a result o f his or her position in the organization. Although

p eop le in positions o f authority are also likely to have reward and coercive power,

legitimate power is broader than the power to coerce and reward.

Coercive power is the power a leader has to punish or control. Followers react to

this power out o f fear o f the negative results that might occur if they do n ot comply.

Managers typically have some coercive power, such as being able to suspend or demote

employees or to assign them work they find unpleasant or undesirable.

Reward power is the power to give positive rewards. These can be anything that a

person values, such as money, favorable perform ance appraisals, prom otions, interest­

ing work assignment, friendly colleagues, and preferred work shifts or sales territories.

Expert power is pow er based on expertise, special skills, or knowledge. If an

employee has skills, knowledge, or expertise that is critical to a work group, that per­

son ’s expert power enhanced.

Finally, referent power is the pow er that arises because o f a p erson ’s desirable

resources or personal traits. If you are adm ired and peop le want to be associated

with you, you can exercise pow er over others because they want to please you.

R eferent pow er develops out o f adm iration fo r another and a desire to be like that

person.

M ost effective leaders rely on several differen t form s o f pow er to affect the

behavior and perform ance o f their followers. For exam ple, the com m anding officer

o f one o f Australia’s state-of-the-art submarines, the HMAS Sheean, employs different

types o f pow er in managing his crew and equipm ent. He gives orders to the crew

thinking critically about

E th ic s

Can You Be Friends w ith Your Manager?

T h e d efin itio n o f fr ie n d on social n etw orking sites such as Facebook and M y S p a c e is

so broad th a t even stran gers m a y tag yo u . But it does not feel w e ird because nothing

really changes w h e n a stran ger does this. H o w ever, w h a t if y o u r boss, w h o is not much

o ld er th an yo u are, asks yo u to be a frien d on th ese sites? W h a t then? W h a t are th e

im p licatio n s if yo u refuse th e offer? W h a t are th e im p licatio n s if yo u accept?

W h a t ethical issues m ig h t arise because o f this? W h a t w o u ld yo u do?

Chapter Sixteen M anagers as Leaders

403

(legitim ate), praises them (reward), and disciplines those who com m it infractions

(coerciv e). As an effective leader, he also strives to have expert pow er (based on

his expertise and know ledge) and referent power (based on his being adm ired) to

influence his crew.34

DEVELOPING TRUST

In today’s uncertain environment, an important consideration for leaders is building

trust and credibility. Trust can be extremely fragile. Before we can discuss ways leaders

can build trust and credibility, we have to know what trust and credibility are and why

they are so important.

The main com pon en t o f credibility is honesty. Surveys show that honesty is con ­

sistently singled out as the num ber-one characteristic o f adm ired leaders. “Honesty

is absolutely essential to leadership. If people are going to follow som eone willingly,

whether it be into battle or into the boardroom , they first want to assure themselves

that the person is worthy o f their trust.”35 In addition to being honest, credible lead­

ers are com petent and inspiring. They are personally able to effectively communicate

their confidence and enthusiasm. Thus, followers ju d ge a leader’s credibility in terms

o f his or her honesty, com petence, and ability to inspire.

Trust is closely entwined with the con cept o f credibility, and, in fact, the terms are

often used interchangeably. Trust is defined as the belief in the integrity, character,

and ability o f a leader. Followers who trust a leader are willing to be vulnerable to the

leader’s actions because they are confident that their rights and interests will n ot be

abused.37 Research has identified five dimensions that make up the con cept o f trust.38

M ustapha Assad, CEO o f Publicis-Graphics,

one o f the leading m edia firm s in the M iddle

East region is described b y one o f his

associates. "C redibility is the cornerstone

o f m y relationship w ith h im ... it is w hat links

us both and is on top o f o u r p rio ritie s ... For

me, m y objective is to rem ain in harm ony as

much as possible w ith him , because it is from

this harm ony that g o o d things com e by, such

as . . . self-control, honesty, transparency, and

professionalism ."36

L e g itim a te p o w e r

E xp ert p o w e r

C red ib ility

The po w er a leader has as a result o f his or her

po sition in an organ izatio n.

Pow er th a t is based on expertise, special skills,

or know ledge.

The degree to w h ich fo llo w e rs perceive som eone

as honest, co m p etent, and able to inspire.

C oercive p o w e r

R efe re n t p o w e r

Trust

The po w er a leader has to punish or control.

Power th a t arises because o f a person's desirable

resources or personal traits.

The b e lief in th e integrity, character, and a b ility

o f a leader.

R ew ard p o w e r

The po w er a leader has to give positive rewards.

404

P a r t F o u r Leading

Meet the M a n a g e r

• Integrity: Honesty and truthfulness

• Competence: Technical and interpersonal knowledge and skills

W HAT IS YOUR ADVICE TO FUTURE

BUSINESS LEADERS?

• Consistency: Reliability, predictability, and g o o d judgm ent in handling situations

Have strong ethics

• Loyalty: Willingness to protect a person, physically and emotionally

and values andI hire

• Openness: Willingness to share ideas and inform ation freely

top candidates

w h o em brace

those eth ics and

values.

O f these five dimensions, integrity seems to be the most critical when som eone

assesses another’s trustworthiness.39 Both integrity and com petence came up in our

earlier discussion o f traits found to be consistently associated with leadership.

Workplace changes have reinforced why such leadership qualities are important.

For instance, the trend toward em powerm ent (which we will discuss shortly) and self­

managed work teams has reduced many o f the traditional control mechanisms used

to m onitor employees. If a work team is free to schedule its own work, evaluate its

own perform ance, and even make its own hiring decisions, trust becom es critical.

Employees have to trust managers to treat them fairly, and managers have to trust

employees to conscientiously fulfill their responsibilities.

Also leaders have to increasingly lead others who may not be in their immediate

work group or even may be physically separated members o f cross-functional or vir­

tual teams, individuals who work for suppliers or customers, and perhaps even people

who represent other organizations through strategic alliances. These situations do

n ot allow leaders the luxury o f falling back on their formal positions for influence.

Many o f these relationships, in fact, are fluid and temporary. So the ability to quickly

develop trust and sustain that trust is crucial to the success o f the relationship.

Why is it im portant that followers trust their leaders? Research has shown that

trust in leadership is significantly related to positive jo b outcom es, including jo b per­

form ance, organizational citizenship behavior, jo b satisfaction, and organizational

com m itm ent.40 Given the im portance o f trust to effective leadership, how can leaders

build trust?

Now, m ore than ever, managerial and leadership effectiveness depends on the

ability to gain the trust o f followers.41 Downsizing, corporate financial misrepresenta­

tion, and the increased use o f temporary employees have determ ined em ployees’ trust

in their leaders and shaken the confidence o f investors, suppliers, and customers.42

Today’s leaders are faced with the challenge o f rebuilding and restoring trust with

employees and with other important organizational stakeholders.

EMPOWERING EMPLOYEES

Empowerment involves increasing the decision-m aking discretion o f workers.

Millions o f individual employees and em ployee teams are making the key operating

decisions that directly affect their work. They are developing budgets, scheduling

workloads, controlling inventories, solving quality problem s, and engaging in similar

activities that until recently were viewed exclusively as part o f the m anager’s jo b .43

Dr. Muhadditha Al Hashimi, the CEO o f Dubai Healthcare City (DHCC) a center for

clinical and wellness services, explains this very convincingly: “My senior leadership

team is quite em powered. They are in their positions because I ’ve trusted them to

b ecom e directors o f those sectors. I want them to use their ju d gm en t to the best o f

their ability.”44

O ne reason m ore com panies are em powering em ployees is the need for quick

decisions by the people who are most knowledgeable about the issues, often those at

lower organizational levels. If organizations want to successfully com pete in a dynamic

global econom y, employees have to be able to make decisions and im plem ent changes

quickly. A nother reason m ore companies are empowering employees is that organiza­

tional downsizings have left many managers with larger spans o f control. In order to

cope with the increased work demands, managers have had to em power their people.

Although em powerm ent is not a universal answer, it can be beneficial when employees

have the knowledge, skills, and experience to do their jo b s competently.

Chapter Sixteen M anagers as Leaders

405

This construction site in D ubai show s the scale

and type o f p ro je ct le d b y Rashid Galadari,

whose G alvest H olding G roup is a m u lti-m illio n

d o lla r real estate company. Galadari is devoted

to developing a m anagem ent structure that

supports his vision fo r the company. He believes

that this cou ld be done through em pow erm ent,

a thing that, he acknowledges, is n o t dom inant

in the M id d le East, as people are n o t used to

g iv in g aw ay th e ir responsibilities. He asserts that

em p ow erm en t is a ll too im p o rta n t fo r success

and g ro w th in this p a rt o f the w o rld.45

LEADING ACROSS CULTURES

O ne general conclusion that surfaces from leadership research is that effective lead­

ers d o n ot use a single style. They adjust their style to the situation. A lthough not

m entioned explicitly, national culture is certainly an important situational variable in

determining which leadership style will be most effective. What works in China is not

likely to be effective in France or Canada. For instance, one study o f Asian leadership

styles revealed that Asian managers preferred leaders who were com petent decision

makers, effective communicators, and supportive o f employees.46

National culture affects leadership style because it influences how followers will

respond. Leaders cannot (and should not) just choose their styles randomly. They

are constrained by the cultural conditions their follow ers have com e to expect.

Exhibit 16-7 provides some findings from selected examples o f cross-cultural leader­

ship studies. Because most leadership theories were developed in the United States,

Exhibit 16-7

• Korean leaders are expected to be paternalistic toward employees.

Cross-Cultural Leadership

• Arab leaders w ho show kindness or generosity w ithout being asked to do so are seen by

other Arabs as weak.

• Japanese leaders are expected to be hum ble and speak frequently.

• Scandinavian and Dutch leaders w ho single out individuals w ith public praise are likely to

embarrass, not energize, those individuals.

• Effective leaders in M alaysia are expected to show compassion w hile using more of an

autocratic than a participative style.

• Effective Germ an leaders are characterized by high perform ance orientation, low compas­

sion, low self-protection, low team orientation, high autonomy, and high participation.

Sources: Based on J. C. Kennedy, "Leadership in M alaysia: Traditional Values, International O utlook," A cadem y

o f M a na g e m en t Executive, A u g ust 2002, pp. 15-17; F C. Brodbeck, M. Frese, and M. Javidan, "Leadership Made

in Germany: Low on Com passion, High on P erform ance" A ca d em y o f M a nagem ent Executive, February 2002, pp. 16-29;

M. F Peterson and J. G. Hunt, "In te rna tio n al Perspectives on International L eadership" Leadership Q uarterly, Fall 1997,

pp. 203-231; R. J. House and R. N. A ditya, "T h e Social S cientific Study o f Leadership: Quo Vadis?" Jo u rn a l o f M anagem ent,

vol. 23 (3), 1997, p. 463; and R. J. House, "Leadership in the Tw enty-First C en tu ry" in A. H ow ard (ed.), The C hanging Nature

o f Work, Jossey-Bass, 1995, p. 442.

E m p o w e rm en t

The act o f increasing the de cision-m a king

discretion o f workers.

406

P a r t F o u r Leading

Arab

Perspectives

Leader Profile: Naguib Sawiris, Chairman

and CEO of Orascom Telecom Holding

According to F orbe s, N agu ib S aw iris is one o f the richest people in th e w o rld , w ith a

fo rtu n e valued at o ver U S $12 billion. "T h e eldest son o f O rascom co n g lo m erate fo u n d e r

Onsi S aw iris has continued to expand his telec o m em p ire in Europe via his holding

com pany, W e ath er Investm ents. In addition to O rascom Telecom , W eather's assets include

Italian phone co m p an y W in d and leading G reek telec o m co m p an ies W in d Hellas and

Tellas. O rascom recently sold its 19 percent stake in Hong Kong billio n aire Li Ka-shing's

Hutchison Telecom m u nicatio n s and also its high-risk Iraq o peratio n, Iraqna, th e first

m o b ile phone p ro vider in Iraq."48

W h e n asked w h a t he believes separates a good business lead er fro m a g reat one,

S aw iris responded: "A g reat business leader, he has a vis io n , he w an ts to fly o ver the

sky and get . . . w h e re nobody's been th e re before. That's a g reat leader. A good lead er is

th e CEO o f a g reat co m p an y th at does w ell and it increases th e revenu e and so on. But

g reat businessm en w o u ld go on to history, like th e typ es of p eo ple w h o built an im p erial

business co rp o ratio n fro m nothing . . . all th e guys [fro m ] eB ay and w ith M icro so ft, these

are g reat le a d e rs "49

they have a U.S. bias. They emphasize follow er responsibilities rather than rights,

assume self-gratification rather than com m itm ent to duty or altruistic motivation,

assume centrality o f work and dem ocratic value orientation, and stress rationality

rather than spirituality, religion, or superstition.47 For example, in the Arab world,

the impact o f religion is pervasive. To exclude the impact o f religion on how people

behave, even in business settings, does n ot work. Take the example o f the Egyptian

business leader, Naguib Sawiris, the legendary chairm an and CEO o f O rascom

Telecom H olding. He does n ot hesitate a bit in indicating the role o f faith in his lead­

ership and in his success. H e indicates that business leadership requires taking risks

and risk taking requires faith. W hen asked about what it takes for a person to take

risks, he responded: “The first word that com es to my mind is faith. I think if you really

believe in G od, you think y o u ’re a g o o d hum an being, then you know h e ’s going

to be on your side so you d o n ’t fear anything. So this has been the biggest source o f

my power.”

However, the GLOBE research program , first introduced in Chapter 4, is the

m ost extensive and comprehensive cross-cultural study o f leadership ever undertaken.

T he GLOBE study has fou n d that there are som e universal aspects to leadership.

Specifically, a num ber o f elements o f transformational leadership appear to be asso­

ciated with effective leadership, regardless o f what country the leader is in.50 These

include vision, foresight, providing encouragem ent, trustworthiness, dynamism, positivity, and proactiveness. The results led two members o f the GLOBE team to conclude

that “effective business leaders in any country are expected by their subordinates to

provide a powerful and proactive vision to guide the com pany into the future, strong

motivational skills to stimulate all employees to fulfill the vision, and excellent plan­

ning skills to assist in implem enting the vision.”51

Some peop le suggest that the universal appeal o f these transformational leader

characteristics is due to the pressure toward com m on technologies and management

practices, as a result o f global competiveness and multinational influences.

UNDERSTANDING GENDER DIFFERENCES AND LEADERSHIP

There was a time when the question “D o males and females lead differently?” could be

seen as a purely academ ic issue: interesting, but n ot very relevant. That time has cer­

tainly passed! Many wom en now hold senior management positions, and many m ore

around the world continue to jo in the m anagem ent ranks. M isconceptions about

Chapter Sixteen M anagers as Leaders

407

the relationship between leadership and gender can adversely affect hiring, perfor­

m ance evaluation, prom otion, and other human resource decisions for both m en and

wom en. For instance, evidence indicates that a “g o o d ” manager is still perceived as

predominantly masculine.52

A num ber o f studies focusing on gender and leadership style have been conducted

in recent years. Their general conclusion is that males and females use different styles.

Specifically, wom en tend to adopt a m ore dem ocratic or participative style. W omen

are m ore likely to encourage participation, share power and inform ation, and attempt

to enhance followers’ self-worth. They lead through inclusion and rely on their cha­

risma, expertise, contacts, and interpersonal skills to influence others. W om en tend

to use transform ational leadership, motivating others by transform ing their self­

interest into organizational goals. Men are m ore likely to use a directive command-andcon trol style. They rely on the form al position authority fo r their influence. Men

use transactional leadership, handing out rewards for g o o d work and punishments

fo r bad.53

There is an interesting qualifier to the findings just m entioned. The tendency for

female leaders to be m ore dem ocratic than males declines when wom en are in maledom inated jobs. Apparently, group norm s and male stereotypes influence wom en,

and in som e situations, wom en tend to act m ore autocratically.54

A lthough it is interesting to see how male and fem ale leadership styles differ,

a m ore im portant question is whether they differ in effectiveness. A lthough some

researchers have shown that males and fem ales tend to be equally effective as

leaders,55 an increasing num ber o f studies have shown that w om en executives, when

rated by their peers, em ployees, and bosses, score higher than their male cou n ­

terparts on a wide variety o f measures.56 Why? O ne possible explanation is that in

today’s organizations, flexibility, teamwork and partnering, trust, and inform ation

sharing are rapidly replacing rigid structures, com petitive individualism, control,

and secrecy. In these types o f workplaces, effective managers must use m ore social

and interpersonal behaviors. They listen, motivate, and provide support to their

p eop le. They inspire and influence rather than control. A nd w om en seem to do

those things better than m en.57

Although women seem to rate highly on the leadership skills needed to succeed in

today’s dynamic global environment, we do not want to fall into the same trap as the

early leadership researchers who tried to find the “one best leadership style” for all situa­

tions. We know that there is n o one best style for all situations. Instead, the most effective

in their leadership styles depends on the situation. So even if men and women differ in

their leadership styles, we should not assume that one is always preferable to the other.

GENDER DIFFERENCES IN LEADERSHIP IN THE ARAB WORLD

Leadership positions in the Arab world have traditionally been m onopolized by men.

The dom inant secular leadership prototype in Arab culture is the Sheik - a male fig­

ure with religious authority.58 While religious and paternalistic traditions o f leadership

and authority persist, there are nevertheless examples o f prom inent wom en leaders

who have managed to break through and reach top decision-making positions despite

prevailing stereotypes and constraints. Some attribute the success o f these female

leaders to their family connections, and their male connections m ore specifically. Even

those who are part o f the recent feminization o f leadership positions in the Arab region

appear to face many o f the same constraints as their predecessors.59 They continue

to perceive themselves as accountable to male scrutiny, stereotypes, and traditional

leadership prototypes. They operate in conditions that are still influenced and shaped

by family, tribe, and religion, and they often have to act in such terms. Such are the

realities o f leadership in the Arab world.

The image o f how a leader should behave and act cannot be separated from the

cultural context and the social contexts within which such an image is form ed. Despite

recen t attempts and initiatives to provide opportunities fo r w om en to em erge as

leaders, the current situation in the Arab world still emphasizes the role o f the male

408

P a r t F o u r Leading

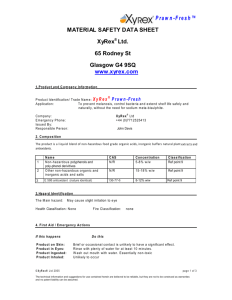

Exhibit 16-8

Female Economic Activity

Rate in Selected World

Regions in 2008.

Female Labor Force

Participation %

Male Labor Force

Participation %

27.0

78.2

Arab States

OECD

56.5

80.1

Least Developed Countries

64.7

85.2

World

56.8

82.6

Source: Human Developm ent Report 2010, "The Real Wealth o f Nations: Pathways to Human Developm ent,"

United Nations Developm ent Programme (UNDP), Palgrave M acm illan, NewYork, NY, USA.

as the dom inant player in society and the woman as submissive. While some may asso­

ciate this polarity to the role o f Islam in Arab society, it is worth noting that Islam

and Islamic history present many examples o f equal opportunity and wom en success

stories. Indeed, in a num ber o f Arab countries, such as Kuwait and M orocco, religion

is used as a platform to advance reform initiatives based on the premise that Islam is

n ot opposed to w om en’s advancement and progress.60

So how can we understand the scarcity o f wom en in top leadership positions in