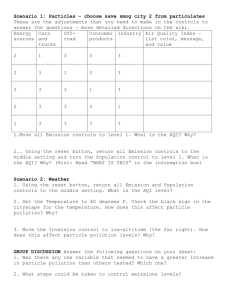

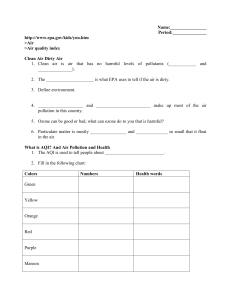

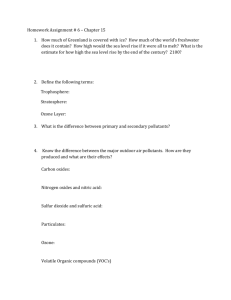

AQI Toolkit for Teachers - Air Quality Partnership: Lehigh Valley

advertisement