What is a fallacy - Doug Lynam's Geometry

advertisement

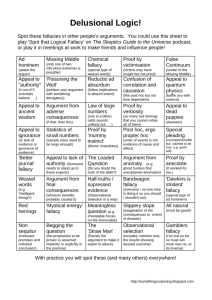

What is a fallacy? A fallacy is an error in a logical argument or a persuasion technique that pushes you toward an unproven or illogical conclusion. Fallacies are used all the time in advertisements, debates, and political campaigns. They are deceptive because they make you think that a conclusion is proven when it is not. The goal of this project is to make you more aware of how logical fallacies work so that you can recognize them and avoid them, thereby making free decisions for yourself. Fallacies were first categorized by Aristotle, and the list has grown ever since. There are many types and variations of logical fallacies, and they often have several names for the same idea. Attached is a list of the most popular fallacies, but a complete list with examples can be found on the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: http://www.iep.utm.edu/f/fallacy.htm, and at the Fallacy Files: http://www.fallacyfiles.org/index.html It is important to note that while fallacies are frequently used to prove absurd conclusions, using a fallacy doesn’t mean the conclusion must be false. The conclusion simply remains unproven. 1) Symbolism: Is used to associate a product or person with a particular word, design, place, idea, music, etc, symbolizing tradition, power, nationalism, religion, sex, family or any other concept with emotional content. Example: Waving an American flag during a political rally, or wearing an American flag pin. 2) Fear or Scare Tactic: Media and politicians often try to make us afraid that if we don’t do or buy something, something bad could happen to us, our families, friends, or country. Example: “We must bomb Turkistan right away or else the Islamofacists will take over the world.” Example: David: My father owns the department store that gives your newspaper fifteen percent of all its advertising revenue, so I'm sure you do not want to publish any story of my arrest for spray painting the college. Newspaper editor: Yes, David, I see your point. The story really isn't newsworthy. David has given the editor a financial reason not to publish, but he has not given a reason why the story is not newsworthy. David has used a scare tactic. 3) Scapegoating: Unfairly blaming many problems on one group of people, race, religion, etc. Example: “The Jews are holding the German people down, so the Jews must be eliminated.” Example: Fortune tellers made predictions for the emperor in ancient Rome. If the prediction failed to come true, the fortune teller would not admit failure, but instead blamed nearby Christians for their evil influence on his powers. By using this reasoning tactic, the fortune teller was scapegoating the Christians. 4) Humor: Making people laugh helps to build trust and puts people at ease, thus making it easier to sell them something or some idea. 1 Example: The Geico caveman commercial. 5) Lying: Intentionally saying something that is known to be false. Most people want to believe what they see. Lies work—on cereal boxes, in ads, and on television news. According to Adolf Hitler, people are more suspicious of a small lie than a big one. Lying can include deliberate distortion of facts, the omission of important facts, or stating false facts. 6) Testimonials: Using a famous person, an authority figure, or respected institution to sell a person, idea, or product. 7) Repetition: Is used to drive a message home many times. Even unpleasant ads or lies work if they are repeated enough to pound their message into our skulls. 8) Flattery: If you make someone feel good they are more likely to buy a product or idea. We like people who like us, and we tend to believe people we like. (I’m sure that someone as brilliant as you will easily understand this technique.) 9) Bribery: Seems to give us something desirable: “Buy one, get on free.” “Earn more cash rewards with your Visa Check Card!” This technique plays on people’s greed. Unfortunately, there is no free lunch and most of these tactics hide the fact that you are getting ripped off. 10) Card stacking, Cherry Picking, or Quoting out of Context: Provides a false context for information, telling only part of the story to give a misleading impression. Read the critic’s quotations in any movie ad and you will only see the compliments included. Example: If a movie critic said, “This is the most shocking movie I have seen in a long time because it was so badly directed and so poorly acted. I am stunned that anyone would pay to see this film.” However, the movie ad only said, “This is the most shocking movie I have seen in a long time…” 11) Nostalgia: People tend to forget the bad parts of the past, and remember the good. A nostalgic setting usually gives a product or idea a better image. Example: Using images from the 1960s to sell Volkswagen vans. 12) Warm and Fuzzy: Using sentimental images like families, kids, pets and animals to sell products. Example: Using images of puppies to sell toilet paper in a Cottonelle commercial. 13) Sex Appeal: Using good-looking models in ads to suggest that we’ll look like a model if we buy the product. Example: Every cosmetic advertisement. 14) Simple Solutions or Over Simplification: Avoiding complexities and offering an easy fix to a complex issue. Example: President Bush wants our country to trade with Fidel Castro's Communist Cuba. I say there should be a trade embargo against Cuba. The issue in our election is Cuban trade, and if you are against it, then you should vote for me for president. Who to vote for should be decided by considering quite a number of issues in addition to Cuban trade. 15) False Scientific Evidence: Using the paraphernalia of science such as charts, graphs, lab 2 coats, etc., to “prove” something that is often bogus. Example: An actor in a white lab coat advertizing a diet pill while showing charts of increased metabolic rates and weight loss, “proving” that a fad diet pill really works. 16) Hyperbole or “Hype”: Exaggerations or using impressive sounding language that is vague and meaningless. Examples: “The best deal ever.” “The greatest automobile advance of the century!” “Blowout sales event of the year!” 17) Ad Hoc Rescue – Making up a reason: Psychologically, it is understandable that you would try to rescue a cherished belief from trouble. When faced with conflicting data, you are likely to mention how the conflict will disappear if some new assumption is taken into account. However, if there is no good reason to accept this saving assumption other than it works to save your cherished belief, your rescue is an ad hoc rescue. Example: Yolanda: If you take four of these tablets of vitamin C every day, you will never get a cold. Juanita: I tried that last year for several months, and still got a cold. Yolanda: Did you take the tablets every day? Juanita: Yes. Yolanda: Well, I'll bet you bought some bad tablets. The burden of proof is definitely on Yolanda's shoulders to prove that Juanita's vitamin C tablets were probably "bad" -- that is, not really vitamin C. If Yolanda can't do so, her attempt to rescue her hypothesis (that vitamin C prevents colds) is simply a dogmatic refusal to face up to the possibility of being wrong. 18) Ad Hominem – Personal Attack, Smear Tactic, or Trash Talking Your Opponent: You commit this fallacy if you make an irrelevant attack on the arguer. Politicians and television talk shows love to use personal attacks to discredit an opponent rather than argue real issues. Example: What she says about Johannes Kepler's astronomy of the 1600s must be garbage. Do you realize she's only fourteen years old and failed her ballet class? An argument should stand or fall on the scientific evidence, not on the arguer's age or anything else about her past. 19) Anecdotal Evidence or Over Generalizing: Using one specific situation to make a general claim, even if it goes against scientific evidence. Look closely at diet ads and get rich quick schemes; there is often in very small print the words, “Results not typical.” Ads often use anecdotal evidence to persuade you that their product will always work. Example: Yeah, I've read the health warnings on those cigarette packs and I know about all that health research, but my brother smokes, and he says he's never been sick a day in his life, so I know smoking can't really hurt you. 20) Appeal to Money :The fallacy of appeal to money uses the error of supposing that, if something costs a great deal of money, then it must be better, or supposing that if someone has a great deal of money, then he or she is a better person in some way unrelated to having a great deal of money. Similarly it's a mistake to suppose that if something is cheap it must be of inferior quality, or to suppose that if someone is poor financially then he or she is poor at something unrelated to having money. Example: He's rich, so he should be the president of our Parents and Teachers Organization. 3 21) Status Symbols: By charging a lot of money for an item or making it available only to wealthy people it becomes more desirable. Example: a Lexus or Mercedes-Benz commercial that shows wealthy, successful people driving big, expensive cars. The implication is that if you drive a particular car then you too are wealthy and successful. 22) Appeal to the People or Mob Appeal or argumentum ad populum: Suggesting strongly that someone's claim or argument is correct simply because it's what most everyone believes. Agreement with popular opinion is not necessarily a sign of truth, and deviation from popular opinion is not necessarily a reliable sign of error. Example: You should turn to channel 6. It's the most watched channel this year. Example: Buy Stinky Brand blue cheese because ten-thousand Frenchmen can’t be wrong. 23) Black-or-White: The black-or-white fallacy unfairly limits you to only two choices. Example 1: Well, it's time for a decision. Will you contribute $10 to our environmental fund, or are you on the side of environmental destruction? This question assumes that if you don’t give $10 you want to destroy the environment. Example 2: I want to go to Scotland from London. I overheard McTaggart say there are two roads to Scotland from London: the high road and the low road. I expect the high road is dangerous because it's through the hills. But it's raining, so both roads are probably slippery. I don't like either choice, but I guess I should take the low road. This would be fine reasoning if you were limited to only two roads, but you've falsely gotten yourself into a dilemma with such reasoning. There are many other ways to get to Scotland. Don't limit yourself to these two choices. You can take other roads, or go by boat or train or airplane. Think of the unpleasant choice as a charging bull. By demanding other choices beyond those on the unfairly limited menu, you thereby "go between the horns" of the dilemma, and are not gored. 24) Equivocation: Equivocation is the illegitimate switching of the meaning of a term during an argument. Example 1: Brad is a nobody, but since nobody is perfect, Brad must be perfect, too. The term "nobody" changes its meaning without warning in the passage. Example 2: I don't approve of political jokes. I've seen too many of them get elected. The term "political jokes" changes meaning in this joke. Example 3: All rivers have banks. All banks have vaults. So, all rivers have vaults. 25) Exaggeration: Overstates or overemphasizes a point out of proportion. Example 1: She's practically admitted that she intentionally yelled at that student while on the playground in the fourth grade. That's assault. Then she said nothing when the teacher asked, "Who did that?" That's lying, plain and simple. Do you want to elect as secretary of this society someone who is a known liar prone to assault? Doing so would be a disgrace to the Collie Society. 26) False Cause: Improperly concluding that one thing is a cause of another. Example: My psychic adviser says to expect bad things when Mars is aligned with Jupiter. Tomorrow Mars will be aligned with Jupiter. So, if a dog were to bite me tomorrow, it would be because of the alignment of Mars with Jupiter. 27) Guilt by Association: Guilt by association occurs when a person is said to be guilty of error because of the group he or she associates with. Example: Secretary of State Dean Acheson is soft on communism as you can see by the fuzzy4 headed liberals who come to his White House cocktail parties and the bleeding hearts of his Democratic Party who call for "moderation and constraint" against Soviet terror. Has any evidence been presented here that Acheson's actions are inappropriate in regards to communism? This sort of reasoning is an example of McCarthyism, the technique of smearing liberal Democrats that was so effectively used by the late Senator Joe McCarthy in the early 1950s. In fact, Acheson was strongly anti-communist and the architect of President Truman's firm policy of containing Soviet power. 28) Loaded Language: This is the use of highly charged words that expresses value judgments which instill a prejudice in the listener. Example: [News broadcast] In today's top stories, Senator Smith carelessly cast the deciding vote today to pass both the budget bill and the trailer bill to fund yet another excessive watchdog committee over coastal development. This broadcast is an editorial posing as a news report. It is the opinion of the broadcaster that the vote was careless and the committee excessive, but they are presented as facts. 29) Begging the Question: This is a type of circular reasoning in which a conclusion is proven by assuming that the conclusion is already correct. The solution is often just a restatement of the original problem. Example 1: "Women have rights," said the Bullfighters Association president. "But women shouldn't fight bulls because a bullfighter is and should be a man." The president is saying basically that women shouldn't fight bulls because women shouldn't fight bulls. This reasoning isn't making any progress toward determining whether women should fight bulls. 30) Red Herring: A red herring is a smelly fish that would distract even a bloodhound. It is also a diversion that leads you off the track of the real argument. Example: Will the new tax in Senate Bill 47 unfairly hurt business? One of the provisions of the bill is that the tax is higher for large employers (fifty or more employees) as opposed to small employers (six to forty-nine employees). To decide on the fairness of the bill, we must first determine whether employees who work for large employers have better working conditions than employees who work for small employers. Bringing up the issue of working conditions is the red herring. 31) Sharpshooter: The sharpshooter's fallacy gets its name from someone shooting a rifle at the side of the barn and then going over and drawing a target and bulls-eye around the bullet hole. The fallacy is caused by overemphasizing random results or making selective use of coincidence. Example: Psychic Sarah makes twenty-six predictions about what will happen next year. When one, but only one, of the predictions comes true, she says, "Aha! I can see into the future." 32) Slippery Slope Argument: Assumes that if one event happens, then a series of catastrophes will follow. For example: “If Vietnam falls to the Communists, then the whole world will fall to Communism.” Or, “If I let one person sleep in class, everyone will be sleeping in class.” Some slippery slope arguments can be reasonable, but a clear chain of causality must be proven, and it should not be used as a scare tactic. Example: Mom: Those look like bags under your eyes. Are you getting enough sleep? Jeff: I had a test and stayed up late studying. Mom: You didn't take any drugs, did you? 5 Jeff: Just caffeine in my coffee, like I always do. Mom: Jeff! You know what happens when people take drugs! Pretty soon the caffeine won't be strong enough. Then you will take something stronger, maybe someone's diet pill. Then, something even stronger. Eventually, you will be doing cocaine. Then you will be a crack addict! So, don't drink that coffee. 33) Straw Man: "Straw man" is one of the best-named fallacies, because it is memorable and vividly illustrates the nature of the fallacy. Imagine a fight in which one of the combatants sets up a man of straw, attacks it, then proclaims victory. All the while, the real opponent stands by untouched. Example:"Senator Jones says that we should not fund the attack submarine program. I disagree entirely. I can't understand why he wants to leave us defenseless like that." Not funding a submarine program will not leave a country defenseless. 34) Traditional Wisdom: Saying or implying that something must be OK today simply because it was a good idea in the past or because that is the way things have always been done. Example: Of course we should buy IBM's computer whenever we need new computers. We have been buying IBM as far back as anyone can remember. The "of course" is the problem. The traditional wisdom of IBM being the right buy is a reason to buy IBM next time, but it's not a good enough reason in a climate of changing products, so the "of course" indicates that the fallacy of traditional wisdom has occurred. 35) Tu Quoque or “And you also”: To defend a person or idea from criticism by turning the critique back against the accuser. Whether the accuser is guilty of the same wrong is irrelevant to the truth of the original charge, but when used as a diversionary tactic, Tu Quoque can be very effective, since the accuser is put on the defensive, and frequently feels compelled to defend against the accusation. Example: You say that it is bad for me to stay out late and party all night, but when you were my age you stayed out late and partied, therefore you must be wrong. Discovering that a speaker is a hypocrite is a reason to be suspicious of the speaker's reasoning, but it is not a sufficient reason to discount it. 36) Two Wrongs Make a Right: When you defend your wrong action as being right because someone previously has acted wrongly. Example: Oops, no paper this morning. Somebody in our apartment building probably stole my newspaper. So, that makes it OK for me to steal one from my neighbor's doormat while nobody else is out here in the hallway. 37) Argument to Pity (arguementum ad misericordiam): This technique uses an appeal to pity, sympathy, or compassion to support a conclusion. For example, a student who does not have a legitimate reason for turning in his Fallacy Project late might argue that if he doesn’t get a high grade his mother will have a heart attack. 38) Fallacy of False Cause (post hoc, ergo propter hoc): This is the error of arguing that because two events happen at the same time or are related to each other, that one is the cause of the other. For example, there might be a genuine correlation between the stork population in Europe and the human birth rate. (Both go up and down together). But it would be an error to conclude that the presence of storks causes babies to be born. 39) Unsupported Claim: Saying that something is true doesn’t always make it true. Stating: 6 “Brother Doug is the best math teacher ever!” does not make it true (or false). 40) Argument from Authority: This argument uses expert opinion or the pronouncement of someone with a position of power, authority, or respect to support a conclusion. This can be used legitimately in some situations (such as a court of law) to prove a point, but can also be used to avoid providing evidence or proof to support a conclusion. Example: “Four out of five doctors agree that Lucky Strike Cigarettes taste the best.” 41) Missing the Point (Ignoratio elenchi): Not answering the question that is asked. Politicians and celebrities often do this when asked a difficult question during an interview. 42) Loaded Question: This tactic puts unfounded assumptions into a question so that any answer given will trap the person answering it. The classic example is the question, “Have you stopped beating your spouse?” No matter how the respondent answers, yes or no, she concedes a) that she has a spouse b) she has beaten that spouse at some time Another example is, “When are you going to stop cheating on your geometry tests?” 43) Fallacy of Misplaced Concreteness: Assumes something to be a unified whole or homogenous group that is not. For example, “What Americans need is a stronger highway system.” This statement assumes that Americans are one solid, concrete, homogenous group. Although the highways system might need repair, not every American needs better highways. Another example is: “What the Iraqi people want is to be free from the tyranny of Saddam Hussein and to live in a democratic society.” Some Iraqis want a democratic society and to live without the rule of Saddam, but not all of them. There are many different factions, ethnicities, and religions in Iraq, each of whom may want something completely different. 44) Plain Folks Appeal: A Plain Folks argument is one in which the speaker presents him or herself as an “average Joe,” a common person who can understand and empathize with a listener's concerns. The most important part of this appeal is the speaker's portrayal of themselves as someone who has had a similar experience, to the listener, and knows why they may be skeptical or cautious about accepting the speaker's point of view. Sources: Internet Encyclopedia of Fallacies: http://www.iep.utm.edu/f/fallacy.htm New Mexico Media Literacy Project The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy The Fallacy Files: http://www.fallacyfiles.org/index.html 7