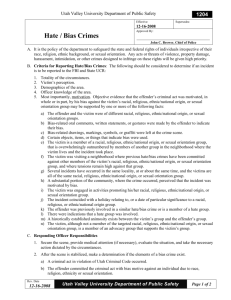

Training Guide For Hate Crime Data Collection

advertisement