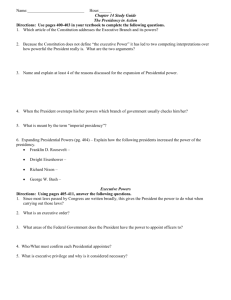

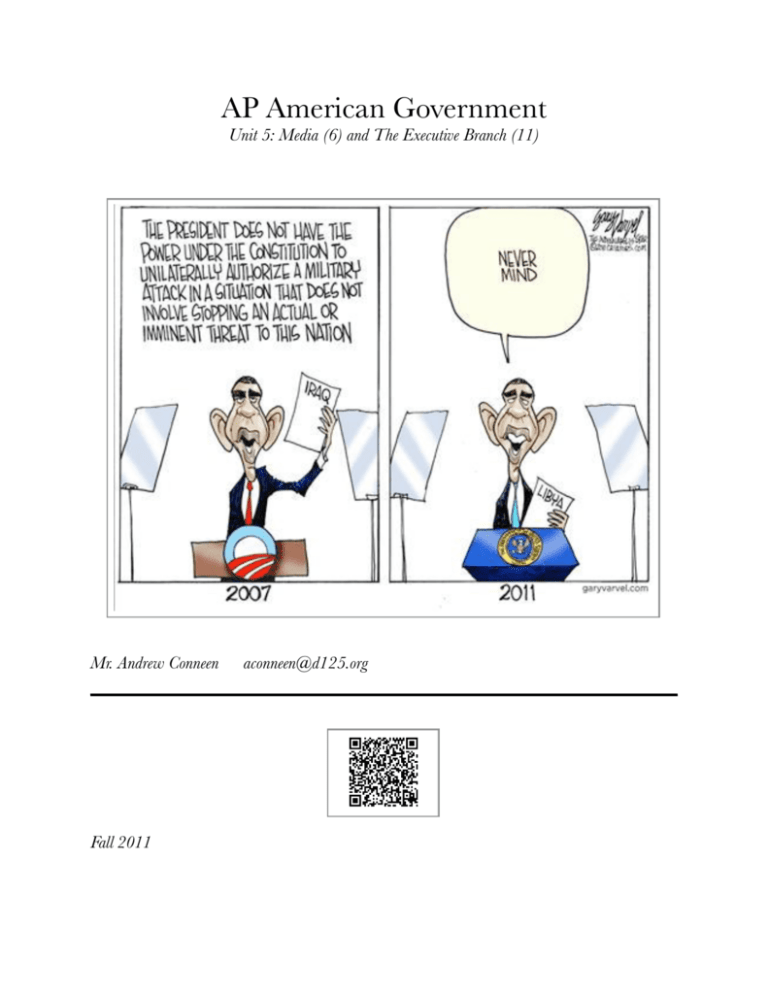

AP American Government

advertisement