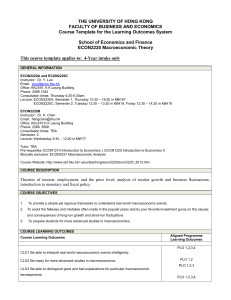

Macroeconomic methodology – from a Critical Realist perspective

advertisement