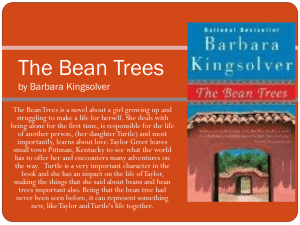

Feminine Voices in The Bean Trees: A Literary Analysis

advertisement