AUTHORS: Rachel A. Bowman, PhD,a and Jeffrey P. Baker, MD, PhD,b on

behalf of Duke University School of Medicine

a

Department of Psychiatry, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North

Carolina; bTrent Center for Bioethics, Humanities, and History of Medicine,

Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina

Address correspondence to Rachel A. Bowman, PhD, Durham Child Development

and Behavioral Health Clinic, Duke University School of Medicine, 402 Trent Drive

#2906, Durham, NC 27705. E-mail: rachel.bowman@duke.edu

Accepted for publication Nov 1, 2013

Drs Bowman and Baker approved the final manuscript as submitted.

KEY WORDS

autism, applied behavioral analysis

ABBREVIATIONS

ABA—applied behavior analysis

UCLA—University of California at Los Angeles

doi:10.1542/peds.2013-2583

Screams, Slaps, and Love: The Strange Birth of

Applied Behavior Analysis

On May 7, 1965, an extraordinary photo

essay titled “Screams, Slaps, and Love”

appeared in the pages of Life magazine. It portrayed the lives of 4 “utterly

withdrawn children whose minds are

sealed against all human contact and

whose uncontrolled madness had

turned their homes into hells.”1 Their

diagnosis was “childhood schizophrenia,” the term applied at the time to

the condition we know as autism. Two

were nonverbal, 2 others had no language other than endlessly repeating

television commercial jingles, and all

4 exhibited very disruptive behaviors

such as head-banging to the point of

bruising.

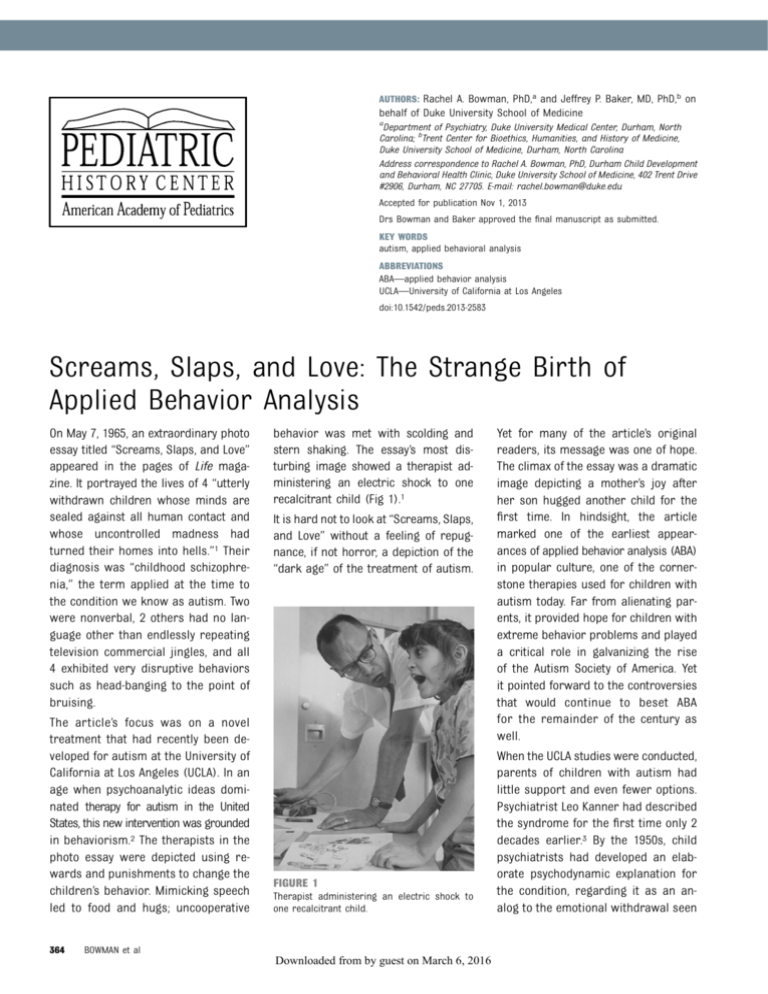

The article’s focus was on a novel

treatment that had recently been developed for autism at the University of

California at Los Angeles (UCLA). In an

age when psychoanalytic ideas dominated therapy for autism in the United

States, this new intervention was grounded

in behaviorism.2 The therapists in the

photo essay were depicted using rewards and punishments to change the

children’s behavior. Mimicking speech

led to food and hugs; uncooperative

364

behavior was met with scolding and

stern shaking. The essay’s most disturbing image showed a therapist administering an electric shock to one

recalcitrant child (Fig 1).1

It is hard not to look at “Screams, Slaps,

and Love” without a feeling of repugnance, if not horror, a depiction of the

“dark age” of the treatment of autism.

FIGURE 1

Therapist administering an electric shock to

one recalcitrant child.

BOWMAN et al

Downloaded from by guest on March 6, 2016

Yet for many of the article’s original

readers, its message was one of hope.

The climax of the essay was a dramatic

image depicting a mother’s joy after

her son hugged another child for the

first time. In hindsight, the article

marked one of the earliest appearances of applied behavior analysis (ABA)

in popular culture, one of the cornerstone therapies used for children with

autism today. Far from alienating parents, it provided hope for children with

extreme behavior problems and played

a critical role in galvanizing the rise

of the Autism Society of America. Yet

it pointed forward to the controversies

that would continue to beset ABA

for the remainder of the century as

well.

When the UCLA studies were conducted,

parents of children with autism had

little support and even fewer options.

Psychiatrist Leo Kanner had described

the syndrome for the first time only 2

decades earlier.3 By the 1950s, child

psychiatrists had developed an elaborate psychodynamic explanation for

the condition, regarding it as an analog to the emotional withdrawal seen

MONTHLY FEATURE

in abused and institutionalized children.4

Bruno Bettelheim, an unconventionally

trained psychoanalyst in Chicago,

brought these ideas to a wide audience in his best-selling 1967 book The

Empty Fortress.5,6 It described his program at Chicago’s Orthogenic School

that removed autistic children from

their allegedly abusive families and

provided an environment allowing complete expression of their “repressed”

egos, to the point of spitting, defecating, and biting caregivers. Reviewers

were moved by the dedication of Bettelheim and his staff, seemingly unaware of the message that was

being foisted on so-called “refrigerator

mothers.”7 In the end, Bettelheim’s data

were shown to be deeply flawed, but

not before they added even greater

misery to the lives of mothers of children with autism.

The philosophy exemplified by ABA

could hardly have been more different.

Its roots were in behaviorism rather

than psychoanalytic theory. Behaviorism began in the early 20th century

and flourished with the work of B.F.

Skinner and colleagues in the mid-20th

century. From the ABA perspective,

treating autism did not require understanding its etiology or parental

dynamics. Instead, changing behavior

was a matter of reward and punishment. ABA’s champion was outspoken

UCLA psychologist Ivar Lovaas, whose

matchless confidence was exemplified

by his oft-quoted claim that had he

treated Adolf Hitler as a young child

he could have turned him into a nice

person.8 Lovaas believed that he could

effectively treat severe childhood problems such as aggression and self-injury

without taking into account underlying etiology, through intensive positive

and negative reinforcement of overt,

external behavior. Although his UCLA

studies were performed in an institutionalized population, he sought to educate

parents to become agents of therapy.9,10

Perhaps predictably, ABA’s most vocal

critic was Bettelheim, who charged

that Lovaas’s work reduced children

to the “level of Pavlovian dogs”5(p410)

and “pliable robots.”5(p412) Such arguments at first appealed to many in the

educated public, who saw Bettelheim

as exemplifying humanistic and progressive values. It was the parents of

children with autism who were most

victimized by his writing and who

would eventually challenge his public

authority.

As detailed by sociologist Gil Eyal and

his colleagues, “Screams, Slaps, and

Love” played an interesting role in this

story.11 Not far away, Bernard Rimland, a Navy psychologist based in San

Diego, ignited what would eventually

become a widespread revolt against

the psychogenic theory of autism. After recognizing that his own son had

autism, Rimland researched and in

1964 published his own book challenging the “refrigerator mother” theory, Infantile Autism.12 Parents wrote

to Rimland requesting help for their

children, but he quickly realized he had

little to offer. After publication of the

1965 Life magazine article, parents inundated both Rimland and Lovaas with

letters pleading for more services and

effective interventions for their children with autism. As a result, Rimland

met Lovaas and observed his work at

UCLA. After trying the therapy on Rimland’s son and seeing progress, Rimland and Lovaas formed an alliance

with a dynamic group of parent advocates. Out of this network emerged the

National Society for Autistic Children,

today’s Autism Society of America.13,14

To be sure, the use of aversive techniques such as electric shock deeply

divided the autism community for many

years. Lawsuits charged that the use of

shock was tantamount to psychological

abuse that could leave lasting emotional trauma.15 Vocal critic C.D. Webster portrayed shock therapy as an

PEDIATRICS Volume 133, Number 3, March 2014

Downloaded from by guest on March 6, 2016

abuse of power by mental health professionals in institutional settings that

should no longer be tolerated.16 Interestingly, few questioned the efficacy

of aversive therapy, and many parents

came to its defense as the only intervention that made their families’ lives

tolerable. Eventually the rise of effective

positive alternatives gave ABA advocates

confidence that positive reinforcement

alone could still be effective.17,18

The 1965 Life magazine article significantly altered the landscape of autism

treatment and research. Although almost a half-century has passed since

its publication, controversy and hope

persist. Despite validation in numerous

studies and the endorsement of the

US surgeon general,19 ABA continues to

be attacked as an overly mechanistic

strategy that fails to generalize to realworld changes in behavior. Such critiques often fail to take into account

that ABA, like autism itself, has come to

incorporate a spectrum of approaches

grounded in shaping behavior in more

naturalistic ways, never including physical punishment. In other words, today’s

ABA is not the ABA of 1965 and does

not include aversive techniques. Nonetheless, “Screams, Slaps, and Love”

foretold of the birth of a cutting-edge

and effective treatment for autism, and

the roles of professionals and parents

were newly defined and intertwined.

Perhaps its greatest legacy was the

establishment of parent and patient

advocacy groups that have continued

to shape autism today.

REFERENCES

1. Moser D, Grant A. Screams, slaps, and love:

a surprising, shocking treatment helps fargone mental cripples. Life. May 7, 1965:90–

96

2. Smith T, Eikeseth SO. O. Ivar lovaas: pioneer

of applied behavior analysis and intervention

for children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41(3):375–378

3. Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective

contact. Nervous Child. 1943;2:217–250

365

4. Baker JP. Autism in 1959: Joey the mechanical boy. Pediatrics. 2010;125(6):1101–1103

5. Bettelheim B. The Empty Fortress: Infantile

Autism and the Birth of the Self. New York,

NY: Free Press; 1967

6. Pollak R. The Creation of Dr. B: A Biography

of Bruno Bettelheim. New York, NY: Simon

and Schuster; 1997

7. Coles R. A hero of our time. New Repub.

1967;156(9):23–24

8. Zarembo A. Obituaries: Ole Ivar Lovaas,

1927–2010; professor pioneered treatment

for autism. Los Angeles Times. August 6,

2010:AA.6

9. Lovaas OI, Berberich JP, Perloff BF, Schaeffer

B. Acquisition of imitative speech by schizophrenic children. Science. 1966;151(3711):

705–707

10. Lovaas OI, Freitas L, Nelson K, Whalen C. The

establishment of imitation and its use for

the development of complex behavior in

11.

12.

13.

14.

schizophrenic children. Behav Res Ther.

1967;5(3):171–181

Eyal G, Hart B, Onculer E, Oren N, Rossi N.

The Autism Matrix. Malden, MA: Polity Press;

2010

Rimland B. Infantile Autism: The Syndrome

and Its Implications for a Neural Theory of

Behaviour. New York, NY: Appleton-CenturyCrofts; 1964

Lovaas I. Strengths and weaknesses of operant conditioning techniques for the treatment of autism. In: Park CC, ed. Research

and Education: Top Priorities for Mentally Ill

Children. Proceedings of the Conference and

Annual Meeting of the National Society for

Autistic Children, San Francisco. Rockville,

MD: US Department of Health, Education, and

Welfare;1970;24–27

Warren F. The role of the national society in

working with families. In: Schopler E, Mesibov

G, eds. The Effects of Autism on the Family.

New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1984:99–115

15. Lichstein KL, Schreibman L. Employing electric shock with autistic children. A review of

the side effects. J Autism Child Schizophr.

1976;6(2):163–173

16. Webster CD. A negative reaction to the use

of electric shock with autistic children. J

Autism Child Schizophr. 1977;7(2):199–204

17. Sullivan RC. Risks and benefits in the treatment of autistic children. J Autism Child

Schizophr. 1978;8(1):99–113

18. Rimland B. A risk/benefit perspective on

the use of aversives. J Autism Child Schizophr. 1978;8(1):100–104

19. U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services. Mental Health: A Report of the

Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental

Health Services, National Institutes of

Health, National Institute of Mental Health;

1999

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Dr Baker’s research is supported by the Josiah Charles Trent Foundation.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to report.

366

BOWMAN et al

Downloaded from by guest on March 6, 2016

Screams, Slaps, and Love: The Strange Birth of Applied Behavior Analysis

Rachel A. Bowman and Jeffrey P. Baker

Pediatrics 2014;133;364; originally published online February 17, 2014;

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2013-2583

Updated Information &

Services

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

/content/133/3/364.full.html

References

This article cites 10 articles, 2 of which can be accessed free

at:

/content/133/3/364.full.html#ref-list-1

Subspecialty Collections

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in

the following collection(s):

Developmental/Behavioral Pediatrics

/cgi/collection/development:behavioral_issues_sub

Autism/ASD

/cgi/collection/autism:asd_sub

Psychiatry/Psychology

/cgi/collection/psychiatry_psychology_sub

Permissions & Licensing

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures,

tables) or in its entirety can be found online at:

/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

Reprints

Information about ordering reprints can be found online:

/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

PEDIATRICS is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

publication, it has been published continuously since 1948. PEDIATRICS is owned, published,

and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point Boulevard, Elk

Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright © 2014 by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All

rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.

Downloaded from by guest on March 6, 2016

Screams, Slaps, and Love: The Strange Birth of Applied Behavior Analysis

Rachel A. Bowman and Jeffrey P. Baker

Pediatrics 2014;133;364; originally published online February 17, 2014;

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2013-2583

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

located on the World Wide Web at:

/content/133/3/364.full.html

PEDIATRICS is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

publication, it has been published continuously since 1948. PEDIATRICS is owned,

published, and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point

Boulevard, Elk Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright © 2014 by the American Academy

of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.

Downloaded from by guest on March 6, 2016