Fiscal and monetary policy lags • Automatic stabilizers

advertisement

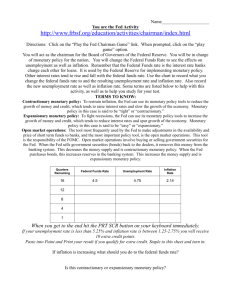

CHAPTER 8 POLICY Chapter Outline: • • • • • • • • • • • Fiscal and monetary policy lags Automatic stabilizers Uncertainties Information feedback Flexibility versus credibility Rules versus discretion Activist rules Fine tuning Policy instruments, indicators, and targets Dynamic inconsistency The independence of the central bank Changes from the Previous Edition: This used to be Chapter 18, starting with Section 18-4. Box 8-1 is new and deals with a monetary policy exercise. The paragraph dealing with the Lucas critique has been eliminated, since this now covered in Chapter 6. Sections 8-4 and 8-6 are also new. The first discusses monetary targets, indicators, and instruments and the second shows practical applications of targeting. Introduction to the Material: Policy makers consistently face the problem of how to respond to an economic disturbance. When contemplating economic stabilization policies, they have to deal with several major difficulties, including: • • • • • There is considerable uncertainty about the structure of the economy and the magnitude of a particular policy response's effect. The process by which policies affect the economy always entails some delays or lags. It is not always clear whether a disturbance is transitory or persistent. The outcome of any policy depends on people's (and firms') expectations and the private sector's reactions to the policy, which are difficult to predict. Policy makers must choose between sudden policy changes and gradual changes, and they need to decide whether they prefer flexibility or credibility in implementing their policy measures. The process by which policy actions affect the economy can be divided into two steps, the inside lag and the outside lag. The inside lag is the time period it takes to implement a policy action after an economic disturbance occurs. It is divided into three parts: 104 • • • the recognition lag, which is the time period that it takes for policy makers to realize that a disturbance has occurred and that a policy response is warranted; the decision lag, which is the time period it takes to decide on the most desirable policy response after a disturbance is recognized; the action lag, which is the time it takes to actually implement the policy measure. Inside lags are shorter for monetary policy than for fiscal policy, since the FOMC meets on a regular basis to discuss and implement monetary policy. Fiscal policy, on the other hand, has to be initiated and passed by both houses of the U.S. Congress and this can be a lengthy process. The outside lag is the time it takes for a policy action, once implemented, to have an effect on the economy. Generally, the outside lag is a distributed lag with a small immediate effect and a larger overall effect over a longer time period. Outside lags are longer for monetary policy than for fiscal policy, since monetary policy actions affect short-term interest rates most directly, while aggregate demand depends heavily on lagged values of income, interest rates, and other economic variables. A change in government spending, on the other hand, immediately affects aggregate demand. If a disturbance is transitory, it may be best not to respond at all, since the disturbance will most likely be over before the policy has an effect. It takes time to bring about change and, as a result, stabilization policy can actually be destabilizing. For small disturbances policy makers may fare best if they rely on automatic stabilizers, which automatically reduce the amount by which output changes as a result of a disturbance. The inside lag of these automatic stabilizers is zero, which is desirable. On the other hand, these automatic stabilizers reduce the effectiveness of stabilization policies, which is undesirable when larger disturbances must be addressed. It is difficult but important to establish whether a disturbance is temporary or longer lasting, since action is required if a disturbance appears to be persistent. After establishing the need for a policy action, policy makers must decide how fast they would like to achieve their desired policy objective. A cold turkey approach has the advantage of adding credibility to a specific announcement, whereas a gradual approach allows for adjustments in moving towards the desired target as new information becomes available. Most economists agree that the Fed should use appropriate indicators to assess whether the available instruments have to be adjusted to achieve an ultimate target. The most appropriate instruments, indicators, and targets depend on the specific situation at hand. Section 8-6 discusses a series of possible targeting approaches, including real GDP targeting, nominal GDP targeting, and inflation targeting. Real GDP targeting is the best option for achieving full employment but is not effective in achieving price stability. By targeting nominal GDP, the central bank creates a policy tradeoff between inflation and unemployment. By targeting inflation, the central bank loses its ability to respond to fluctuations in unemployment. Which targeting approach should be chosen depends greatly on one's belief of how steep or flat the Phillips curve is. Problems in conducting stabilization policy also arise from the difficulties in integrating expectations into the macroeconomic models used to forecast the behavior of the economy. This is especially important since the actions of policy makers affect the expectations on which the actions of the private sector are based. Failure to take these expectations (and reactions resulting from them) into account is guaranteed to lead to inaccurate predictions of the effects of government policies. Policy makers know that their policy actions are much more effective if they have credibility. If policy announcements are believed (and understood), then people will adjust to them much more rapidly. But credibility is only earned by consistent behavior over the long run, and is easily lost if policies change too frequently. The public's reaction to a policy depends on expectations, so careful modeling of the public's responses to government policies is important. Otherwise successful stabilization policy is not feasible. Policy makers may consider a range of predictions about the effects of a policy measure, but any activist 105 policy runs the danger of failing if the information available is poor. There is considerable uncertainty about how well economic models actually represent the workings of the economy. Furthermore, future unanticipated shocks cannot be taken into account at the time a policy is implemented and this increases the danger of actually destabilizing the economy. The best approach to stabilization policy is probably to use caution and diversify with weaker doses of both fiscal and monetary policy. An overly ambitious policy of trying to keep the economy at full-employment at all times (fine tuning the economy) bears great risk, since a full-employment bias often leads to higher inflation. The debate over whether to pursue discretionary policy or follow a rule centers around the tradeoff between credibility and flexibility. While discretionary policy has the advantage of giving policy makers the flexibility to react to disturbances, policy rules allow for more certainty about future government actions and thus create more rational expectations among the private sector in anticipating policy measures. If policy rules are clearly established and followed, then policy makers can, on occasion, respond more effectively to a large disturbance without losing credibility. It should be noted that it is possible to design activist monetary policy rules. Equation (8), which links changes in monetary growth to changes in the unemployment rate, serves as an example for such an active monetary policy rule. But even if a policy rule has been established, it must be clear who has the authority to change the rule if necessary. Policy makers also have to decide whether they should announce in advance what policies they will follow. Such announcements can be more harmful than helpful in cases where the announced targets are abandoned. In such cases, policy makers lose their reputation for displaying consistent behavior. The problem of dynamic inconsistency, that is, the fact that policy makers often are tempted to take short-run actions that will impede their long-run goals, should also be considered. Clearly a goal of full employment with little or no inflation is desirable. However, because of the short-run tradeoff between unemployment and inflation, it is not possible to immediately lower inflation and unemployment simultaneously. Therefore, when anti-inflationary policies are implemented and the unemployment rate rises, politicians are often tempted to address the unemployment problem. However, such action will impede their anti-inflation policy. One way around this problem is to establish a truly independent central bank with a clear mandate to fight inflation. Countries with independent central banks tend to have lower average inflation rates. Suggestions for Lecturing: The purpose of stabilization policies is to counteract economic disturbances that may arise from changes in private or public spending, wars, technological innovations, changes in supply conditions, or a wide range of other occurrences. But policy makers themselves may just as well cause disturbances. If policy measures are based on short-term political goals or simply on poor information, they may actually destabilize the economy. Policy makers face a variety of problems that should be pointed out to students. For one, it is not always clear whether disturbances are temporary or persistent. If a disturbance is only temporary, then the government may be better off not taking any action at all. It not only takes a fair amount of time to develop and enact an appropriate policy response, but it also may take a considerable amount of time for a policy measure to have the desired effect on the economy. Part of the effect of any disturbance is offset by automatic stabilizers (the income tax system, unemployment insurance, the Social Security system, etc.), which do not have any inside lags. As active policy responses to small disturbances are likely to be destabilizing, it is better to rely on such automatic stabilizers to fine tune the economy. However, automatic stabilizers are insufficient for more severe economic disturbances. Larger and more persistent disturbances require appropriate policy actions, in spite of the difficulties that taking action may pose. 106 Unfortunately, the automatic stabilizers reduce the size of the fiscal policy multiplier and therefore the effectiveness of fiscal stabilization policies. Chapter 9 mathematically derives the government spending multiplier, and instructors may want to postpone a more in-depth discussion of how the fiscal policy multiplier is affected by automatic stabilizers until later. Instructors should clearly point out the distinction between inside and outside lags. Inside lags tend to be discrete, that is, of a specified length, whereas outside lags are distributed over time. The inside lag, which is a combination of the recognition, decision, and action lags, is much longer for fiscal policy than for monetary policy. Fiscal policy has to be initiated and passed by both houses of Congress, which can be a lengthy process, as can be seen in the ongoing debate on tax reform or any Social Security reform. Monetary policy can be implemented much more quickly since the FOMC meets on a regular basis to discuss and decide on monetary policy actions. On the other hand, the outside lag, which is generally a distributed lag, which takes account of the effects of a policy action over time, is much shorter for fiscal policy than for monetary policy. A change in government spending affects aggregate demand immediately, leading to a further series of induced changes in output and spending. But monetary policy actions must first change short-term interest rates, then long-term interest rates, and then the level of investment spending before its full effects are felt. The reluctance of the government to make hard choices reflects the difficulties encountered in achieving successful discretionary fiscal policy. On the other hand, the successful record of the discretionary monetary policy approach taken by the Fed for most of the past two decades appears to indicate that an activist monetary policy can be effective. Based on the argument that the lags for monetary policy are long and variable and that our knowledge of the workings of the economy is fairly limited, some economists favor some form of a monetary growth rule. They argue that a strict monetary growth rule with announced targets would greatly reduce the uncertainty the private sector faces when forming inflationary expectations. Not everyone agrees with this assessment, however, and the discussion of whether to follow a rule or to pursue discretionary policy centers around the tradeoff between credibility and flexibility. While discretionary policy has the advantage of giving policy makers the flexibility to react to disturbances, policy rules allow for more certainty about future policy actions. This creates more rational expectations in the private sector and a quicker return to full employment. In addition, these rules reduce all kinds of political pressure. It should be noted that policy makers have a hard time earning credibility and that credibility is easily lost if policies are changed frequently. In the debate over rules versus discretion, it is important to note that policy rules do not have to be passive. An active monetary policy rule is represented in Equation (8), which suggests that the money supply growth rate should be increased by two percent for every one percent increase in the unemployment rate over the natural rate. In this case, an anticyclical monetary policy is achieved without discretion, allowing the public to anticipate the government's action. Government policies affect private sector expectations and actions. But at the same time, private sector expectations and actions affect the success of government policies. The government must be consistent enough in its policy decisions to enable the private sector to anticipate fairly accurately what the government will do in a particular situation. If policy actions can be correctly anticipated, markets will clear more quickly, and stabilization policy will be much more effective. Econometric models, which consist of a set of equations that are based on past economic behavior, are generally used to forecast the effects of various policy options. It is important to emphasize that such models come in all shapes and sizes. One cannot generalize that the more comprehensive models always produce better forecasts. No model is a perfect image of the economy and we still do not really know how the economy works. Therefore we should view forecasts only as best guesses, based on incomplete information and subject to modifications as unexpected events take place. 107 Having been exposed to a great number of graphs in their economics classes, students often picture government economists in Washington looking at similar graphs and trying to determine which curve has shifted to cause a disturbance. Students may not be aware that these economists think in terms of statistical data presented in tables or obtained through regression analysis. It is therefore important to at least briefly discuss how econometric models work. It is an even better idea to have students collect data on some economic variables on their own, and require them to interpret their importance or the relationships among them. The following question can then be posed: Do the simple graphical frameworks used in class provide an adequate tool for forecasting? In many cases, students may agree that, while these graphs cannot show the magnitude of a change, they do at least show the direction certain key variables are expected to take after a disturbance has occurred. Policy makers have to make decisions under a great deal of uncertainty. First, they do not know how well the forecasting model they use reflects the economy. Second, they never know how the public will respond to particular policies and thus cannot be sure of the magnitude of the impact that policy actions will have. Therefore it is always best to proceed cautiously. But in reality policy makers tend to be overly ambitious and often create problems for themselves. Politicians who have lots of discretion are easily tempted to implement policies that address short-run concerns even though these actions may threaten a desired long-term goal. This is known as dynamic inconsistency. The following example may highlight this concept vividly in students' minds. Assume you are the president of your country and you have to deal with an extremist group. They have taken hostages and have threatened to kill them unless their demand to free one of their members (who is incarcerated for having committed a violent crime) from prison is fulfilled. Will you give in to these demands? Your longterm goal is to establish the fact that the government cannot be held hostage to unreasonable demands. Otherwise extremists are likely to take further hostages so they can make further demands. However, if the hostages are killed, then you will be blamed for it. This may not only disturb your good conscience but also threaten your upcoming re-election. Chances are, you will make a deal and hope that you will find a way to deal with the extremists before they strike again. Obviously, this example does not deal with fiscal or monetary policy responses to a disturbance. However, it highlights the dilemma that policy makers have to face constantly: Should we stick to a previously established objective or should we adjust our actions as circumstances warrant? Similarly, it highlights the trade-off between the desire for credibility or flexibility. One way around the problem of dynamic inconsistency is to impose strict rules. Another is to establish a central bank that has a clear mandate to keep inflation low and is largely independent from political pressures by the administration. Empirical evidence shows that countries with independent central banks consistently have lower inflation rates. Chapter 8 discusses the use of instruments, indicators, and targets as well as three different targeting approaches: real GDP targeting, nominal GDP targeting, and inflation targeting. This discussion reinforces how different views of the shape of the Phillips curve can determine the policy approach that is chosen by government decision makers. However, as these issues are discussed again in Chapter 16 in conjunction with the way the Fed operates, some instructors may want to postpone an in-depth discussion of the use of the appropriate instruments, indicators, and targets until later. Additional Readings: Bernanke, et. al., "Missing the Mark: The Truth about Inflation Targeting," Foreign Affairs, September/October, 1999. Bernanke, B. and Mishkin, F., “Inflation Targeting: A New Framework for Monetary Policy?” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Spring, 1997. 108 Blinder, Alan, "Central Banking in a Democracy," Economic Quarterly, FRB of Atlanta, Fall, 1996. Cechetti, Stephen, “Policy Rules and Targets: Framing the Central Banker’s Problem,” Economic Policy Review, FRB of New York, June, 1998. Clarida, Richard, et. Al., “The Science of Monetary Policy: A New Keynesian Perspective,” Journal of Economic Literature, December, 1999. Clark, Todd, "Nominal GDP Targeting Rules: Can They Stabilize the Economy?" Economic Review, FRB of Kansas City, Third Quarter, 1994. Cogley, Timothy, "Why Central Bank Independence Helps to Mitigate Inflationary Bias," Economic Letter, FRB of San Francisco, May, 1997. Diebold, Francis, “The Past, Present, and Future of Macroeconomic Forecasting,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Spring, 1998. Dittmar R. and Gavin, W., ”What Do New-Keynesian Phillips Curves Imply for Price-Level Targeting?” Review, FRB of St. Louis, March/April, 2000. Fischer, Stanley, "Why Are Central Banks Pursuing Long-Run Price Stability?" in Achieving Price Stability, FRB of Kansas City, 1996. Friedman, Benjamin, "Targets, Instruments, and Indicators of Monetary Policy," Journal of Monetary Economics, October, 1975. Havrileski, Thomas, "Electoral Cycles in Economic Policy," Challenge, July/August, 1988. Heller, Walter, "Activist Government: Key to Growth," Challenge, March/April, 1986. Koenig, Evan, “Is the Fed Slave to a Defunct Economist?” Southwest Economy, FRB of Dallas, September/October, 1997 King, R. and Wolma, A., "Inflation Targeting in a St. Louis Model of the 21st Century," Review, FRB of St. Louis, May/June, 1996. Melzer, Thomas, “Credible Monetary Policy to Sustain Growth,” Review, FRB of St. Louis, July/ August, 1997. McNees, Stephen, "An Assessment of the 'Official' Economic Forecasts," New England Economic Review, July/August, 1995. McNees, Stephen, "How Large Are Economic Forecast Errors?" New England Economic Review, July/August, 1992. Poole, William, "Monetary Policy Rules?" Review, FRB of St. Louis, March/April, 1999. Poole, William, "A Policy Maker Confronts Uncertainty," Review, FRB of St. Louis, September/October, 1998. Rudebusch, Glenn, "Is Opportunistic Monetary Policy Credible?" Economic Letter, FRB of San Francisco, October 4, 1996. Stark, T., and Taylor, H., "Activist Monetary Policy for Good or Evil? The New Keynesians vs. the New Classicals," Business Review, FRB of Philadelphia, March/April, 1991. Svensson, Lars, “Price Level Targeting vs. Inflation Targeting: A Free Lunch?” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, August, 1999. Learning Objectives: • • Students should be able to define inside and outside lags and explain their importance in assessing active stabilization policies. Students should understand the concept of automatic stabilizers. 109 • • • • • • • • Students should be aware that the workings of the economy are still not completely understood, and that many questions remain unanswered, including how expectations are formed and what the bases for the private sector's reactions to policy measures are. Students should be aware that poor information and uncertainty about the accuracy of economic models may lead to policy measures that are ineffective or even destabilizing. Students should know the pitfalls of a cold turkey approach versus a gradualist approach. Students should be familiar with the instruments, indicators, and targets of monetary policy. Students should be aware of the difference between real GDP targeting, nominal GDP targeting, and inflation targeting. Students should be aware that the “rules versus discretion” approach often implies a tradeoff between flexibility and credibility and should be able to discuss the merits of each policy approach. Students should understand the concept of dynamic inconsistency. Students should be able to discuss the desirability of an independent central bank. Solutions to the Problems in the Textbook: Conceptual Problems: 1. The first question you should ask yourself as a policy maker is whether a disturbance is transitory or persistent. You should then ask yourself how long it would take to put a suggested policy measure into effect and how long it will take for the policy to have the desired effect on the economy. In addition, you need to know how reliable the estimates of your advisors are about the effects of the policy. If a disturbance is small and probably transitory, you may be best advised to do nothing, because any measure you take is likely to have its effect after the economy has recovered. Therefore your action might only further aggravate the problem. 2.a. The inside lag is the time it takes after an economic disturbance has occurred to recognize and implement a policy action that will address the disturbance. 2.b. The inside lag is divided into three parts. First, there is the recognition lag, that is, the time it takes for policy makers to realize that a disturbance has occurred and that a policy response is warranted. Second, there is the decision lag, that is, the time it takes to decide on the most desirable policy response after a disturbance is recognized. Finally, there is the action lag, that is, the time it takes to actually implement the policy measure. 2.c. Inside lags are shorter for monetary policy than for fiscal policy since the FOMC meets on a regular basis to discuss and implement monetary policy. Fiscal policy, on the other hand, has to be initiated and passed by both houses of the U.S. Congress and this can be a lengthy process. The exceptions are the so-called automatic stabilizers; however, they only work well for small and transitory disturbances 2.d Automatic stabilizers have no inside lag; they are endogenous and function without specific government intervention. Examples are the income tax system, the welfare system, unemployment insurance, and the Social Security system. They all reduce the amount by which output changes in response to an economic disturbance. 110 3.a. The outside lag is the time it takes for a policy action, once implemented, to have its full effect on the economy. 3.b. Generally, the outside lag is a distributed lag with a small immediate effect and a larger overall effect over a longer time period. The effect is spread over time, since aggregate demand responds to any policy change only slowly and with a lag. 3.c. Outside lags are longer for monetary policy since monetary policy actions affect short-term interest rates most directly, while aggregate demand depends heavily on lagged values of income, interest rates, and other economic variables. A change in government spending, however, immediately affects aggregate demand. 4. Fiscal policy has smaller outside lags, but significant inside lags. Monetary policy, on the other hand has smaller inside lags and longer outside lags. Therefore large open market operations should be undertaken to get an immediate effect, but they should be partially reversed over time to avoid a large long-run effect. If the shock is sufficiently transitory and small, policy makers may be best advised not to undertake any policy change at all. 5.a. An econometric model is a statistical description of all or part of the economy. It consists of a set of equations that are based on past economic behavior. 5.b. Econometric models are generally used to forecast the behavior of the economy and the effects of alternative policy measures. 5.c. There is considerable uncertainty about how well econometric models actually represent the workings of the economy. There is also great uncertainty about the expectations of firms and consumers and their reactions to policy changes. Any policy is bound to fail if the information on which it was based is poor. 6. The answer to this question is student specific. The main difficulties of stabilization policy arise from three sources. First, policy always works with lags. Second, the outcome of any policy depends on the way the private sector forms expectations and how those expectations affect the public's behavior. Third, there is considerable uncertainty about the structure of the economy and the shocks that hit it. It can be argued that a monetary policy rule would greatly reduce uncertainty about the Fed's policy responses. If the government behaved in a consistent way, then the private sector would also behave more consistently and economic fluctuations could be greatly reduced. A monetary growth rule would also reduce any political pressure the administration might exert on the Fed. It is often initially unclear whether a disturbance is temporary or persistent and a monetary policy rule would prevent policy mistakes in cases where the disturbance is, in fact, temporary. If active monetary policy is applied to a temporary disturbance, then the lags involved will guarantee that the economy will actually be destabilized. On the other hand, the workings of the economy are not completely understood and events cannot always be predicted. Thus it is difficult to argue for a fixed policy rule. Unanticipated large disturbances warrant an activist policy, especially if they appear to be persistent. It is also possible to construct a more activist monetary growth rule. For example, Equation (8) suggests that the annual 111 monetary growth rate should be increased by two percent for every one percent that unemployment increases above its natural rate. Such a rule is based on the quantity theory of money equation (which relates money supply growth to the growth of nominal GDP) and on Okun's law (which relates the unemployment rate to economic growth). Obviously, because of the long lags for monetary policy, any monetary growth rule will work much better in the long run than in the short run. Fiscal policy rules may make more sense than monetary policy rules, since fiscal policy has long inside lags but shorter outside lags. In a way, built-in stabilizers, although generally not considered "rules", already provide some stability without any inside lag. Many of the arguments against monetary policy rules are also valid for fiscal policy rules and many economists oppose them. The frequently proposed constitutional amendment requiring an annually balanced budget is an example of a fiscal policy rule. There are significant problems associated with such an amendment, since it would greatly limit the government's ability to undertake active fiscal stabilization policy. 7. The arguments for a constant growth rate rule for money are based on the quantity theory of money equation, that is, MV = PY. From this equation we can derive %∆P = %∆M - %∆Y + %∆V. If the long-run trend rate of real output (Y) and the long-run trend of velocity (V) are assumed to be fairly stable, and if wages and prices are sufficiently flexible, then a constant monetary growth rate (M) would insure a constant rate of inflation, that is, a constant rate of change in the price level (P). Also, since monetary policy has long outside lags, active monetary policy can actually be more destabilizing than stabilizing. In addition, since we do not know exactly how the economy works or may react to specific policies, it is best to follow a rule rather than undertake actions that have uncertain outcomes. However, rules are not without problems, as they would not allow flexibility in responding to major disturbances. 8. Dynamic inconsistency occurs if, after having committed themselves to a specific policy action designed to achieve a long-run objective, policy makers find themselves in a situation where it seems advantageous to abandon their original policy, in order to achieve a short-run goal. Such action will impede the long-run objective. 9. Real GDP targeting is the best option if the primary policy goal of monetary policy is to achieve full employment. If policy makers forecast potential GDP correctly, then full employment combined with low inflation can be achieved. However, real GDP targeting bears the greater risk that the secondary goal of achieving a low inflation rate will be missed. If the rate at which potential GDP grows is overestimated, then policy makers may stimulate the economy too much. In this case, they will not be successful in achieving price stability. By targeting nominal GDP, the central bank creates a policy tradeoff between inflation and unemployment. If the rate at which potential GDP grows is overestimated and policy makers stimulate the economy too much, we will get less growth but also 112 less inflation than under real GDP targeting. Which targeting approach should be chosen depends greatly on how steep or flat the Phillips curve is perceived to be. Technical Problems: 1. If actual GDP is expected to be $40 billion below the full-employment level and the size of the government spending multiplier is 2, then government spending should be increased by $20 billion over its current level. For the next period, when actual GDP is expected to be $20 billion below potential, government spending should be cut by $10 billion from its new level, that is, to $10 billion over its original level. In period three, when actual GDP is expected to be at its full-employment level, the level of government spending should again be cut by $10 billion from the last period's level to bring it back to the original level of Period 0. 2.a. If there is a one-period outside lag for government spending, then nothing can be done to close the current GDP-gap. The government should decide to spend $10 billion more for the next period and reduce spending again to its original level after that. 2.b. Graph I below shows the path of GDP for Problem 1 with no outside lag and Graph II shows the path of GDP for problem 2.a. with a one-period outside lag. In each of the graphs the path of actual GDP is shown, first assuming that no policy action takes place and then assuming that the policies proposed in Problems 1 and 2.a. are undertaken. Graph I GDP GDP potential GDP potential GDP 0 time 0 GDP with fiscal policy time GDP without fiscal policy Graph II GDP GDP potential GDP potential GDP 0 time GDP with fiscal policy 0 time GDP without fiscal policy 113 3.a. Since the government multiplier for the first period is 1, the level of government spending must be increased by ∆G = $40 billion to close the GDP-gap of $40 billion. But since the government multiplier in the next period for the amount spent in this period is 1.5, the effect of an increase in government spending in the first period by $40 billion would be an increase in GDP by $60 billion in the second period. 3.b. For the second period a GDP-gap of $20 billion is expected. However, as we saw in 3.a., GDP will increase by $60 billion in the second period if the government increases spending by $40 billion in the first period. Therefore, the government has to reduce spending in the second period by $40 billion from its new level (back to its original level), since the multiplier for a spending change in the same period is 1. 3.c. In this problem, fiscal policy has an outside lag. This means that the effect of an increase in government spending is felt both in the period in which the spending increase takes place and (to an even larger degree) in the following period. The increase in government spending needed to close the GDP-gap in the first period is guaranteed to overshoot the desired goal in the next period. Thus the government will be forced to reverse its increase in spending to the original level in the second period to offset the destabilizing effect. In a case like this, the government has to be much more active in its fiscal policy than in a situation where no distributed lag exists. 4. If there is uncertainty about the size of the multiplier, then fiscal policy becomes much more complicated. If the multiplier is 1, then an increase in government spending by $40 billion will close the GDP-gap in the first period. If the multiplier is 2.5, we will overshoot potential GDP by $60 billion. An increase in spending by 40/2.5 = $16 billion is optimal if the multiplier is 2.5. Thus a cautious government will probably increase spending by no more than $16 billion in the first period, and then reduce the level of spending by $8 billion in the next period ($8 billion above the original level). Such a policy action is designed to close the GDP-gap to some degree over the first two periods while never overshooting potential GDP. In Period 3 we will again be back at the fullemployment level. The extent to which a less cautious government might exceed these suggested spending increases depends largely on that government's level of concern about unemployment versus inflation. 5. To follow an established rule for its policy, the Fed needs to know the source of each disturbance. If a disturbance comes from the goods sector, it is better to have a monetary growth target; if the disturbance comes from the money sector, it is better to have an interest rate target. a. Assume a disturbance comes from the money sector. If an increase in money demand increases the interest rate, the Fed should try to maintain a constant interest rate by increasing the supply of money. This will re-establish the old equilibrium values of the interest rate and output and effectively offset the disturbance. b. Assume a disturbance comes from the goods sector. If an increase in autonomous investment increases the interest rate, then it is not advisable to maintain a constant interest rate. Trying to lower the interest rate again by increasing the money supply would aggravate the disturbance. On the other hand, maintaining a constant money supply, while not offsetting the disturbance, will at least not make things worse. 114 6.a. Students will have to check the Federal Reserve Bulletin in early 2000 and compare the forecasts of the Federal Reserve Board with the actual performance of the economy in 1999. 6.b. Regardless of how detailed it is, no econometric model can accurately represent the economy, since we do not completely understand the way the economy works. Therefore, we can never expect perfect forecasts. It is impossible to incorporate all the relevant information on which individuals and firms base their expectations about the future and to determine how these expectations affect actions in any given situation. Forecasts are generally based on the information available at the time, which may be flawed or outdated. In addition, any unexpected change, such as a supply shock, an unanticipated international change, or an unanticipated domestic policy change, can render the initial predictions wrong. Additional Problems: 1. Define and distinguish between inside and outside lags. The inside lag is the time period it takes to implement a policy action after an economic disturbance is recognized. It is divided into the recognition lag (the time it takes for policy makers to realize that a disturbance has occurred and that a policy response is warranted), the decision lag (the time it takes to decide on the most desirable policy response), and the action lag (the time it takes to implement the policy measure). The outside lag is the time it takes for a policy measure, once implemented, to have an effect on the economy. 2. How do long lags in investment spending affect the usefulness of a government policy that tries to stabilize the economy via investment tax credits? Long lags in investment spending suggest that investment tax credits should not be used for fine-tuning but may be useful in responding to a prolonged disturbance. However, the lag is much shorter for temporary investment tax credits, which often speed up existing or planned investments. Therefore investment tax credits can be used for short-run stabilization, even though uncertainty about their frequency and duration may create unstable swings in investment spending. 3. "Monetary policy should be employed only sparingly since it operates with long and variable lags." Comment on this statement. There are lags both in recognizing that there is a need for a policy response to a disturbance and in designing a particular policy measure. Once the program is in place, it takes additional time to affect economic activity. For example, expansionary monetary policy lowers short-term interest rates and then, after a lag, also lowers long-term interest rates, which, in turn, increases investment spending. Before committing themselves to increased investment spending, firms need to determine whether the cost of capital has risen temporarily or permanently. Ultimately, aggregate demand is affected and then a series of induced adjustments in output and spending will take place. Therefore, while the inside lags for monetary policy actions are short, it takes time for monetary policy to affect aggregate demand to the desired degree since there is an additional distributed lag (the dynamic multiplier process). If monetary policy is employed, it should be done with caution, since it can be destabilizing. But the fairly successful 115 monetary policy of the Fed over the last two decades indicates that it is possible to undertake active monetary policy without destabilizing the economy. 4. "Monetary stabilization policy is difficult for the Fed because of the existence of long and variable outside lags. But if the Fed knew the exact length of these lags, active monetary stabilization policy would always be successful." Comment on this statement. If lags are long and variable, it becomes very difficult to predict exactly when a certain policy measure is going to have its desired effect on the economy. It is thus difficult to successfully implement countercyclical stabilization policies. If the timing of a policy measure is misjudged, the economy may actually be destabilized rather than stabilized. If lags were long but fixed, it would be much easier to judge when to implement a policy measure. However, this is unrealistic since there is still considerable uncertainty about the workings of the economy and about the accuracy of the theoretical models used in forecasting. 5. Is the fact that economists often put decimal points in their forecasts an indication that they can be very accurate in their predictions? Why or why not? The econometric models from which economic forecasts are derived are based on the historical record of the economy. However, not every disturbance can be predicted with accuracy. An economic forecast represents only a best estimate of how the economy will behave based on (often incomplete) information and a set of initial assumptions. A forecast of 1.5% real economic growth should be interpreted as growth anywhere in the range of 1 to 2 percent. 6. True or false? Why? "The Fed can always maintain full employment if it uses its policy instruments appropriately." False. Monetary policy works with long and variable outside lags. Furthermore, by the time the Fed has identified the source and duration of an economic disturbance and decided on the appropriate response, the shock will already have done some damage. Fine tuning the economy through the use of monetary policy is impossible. 7. True or false? Why? "Announcing a policy may be just as effective as actually implementing it." False. There may be short-run effects of policy announcements if individuals act in anticipation of the announced change. Such announcements in and of themselves, however, do not have lasting implications for economic activity unless the government consistently follows through with the proposed policy. Indeed, making announcements and then not following through threatens the credibility and reputation of policy makers and may ultimately render policy announcements destabilizing. 8. "Policy makers committed to full employment encounter major problems if they underestimate the natural unemployment rate." Comment on this statement. 116 Policy makers, who assume that the natural rate of unemployment is 4% rather than its actual 5.5%, will try to stimulate the economy through expansionary policies as soon as the rate of unemployment goes above 4%. But this will decrease unemployment only temporarily since the economy has a tendency to go back to the true natural rate. To maintain the 4% level, policy makers will have to stimulate the economy again and again which will, in turn, create inflationary pressure. Since inflation reduces real wages, workers will ask for wage increases and we will enter the so-called wage-price spiral. 9. Briefly discuss the arguments for and against fine tuning the economy. Fine tuning the economy involves the use of policy tools to counteract every disturbance in the economy, even small ones. Since there are lags in stabilization policies and considerable uncertainty about whether a disturbance is temporary or permanent, a very active stabilization policy in the face of very small disturbances may actually be destabilizing. If a decision to fine tune is made, minimal initial policy responses to economic disturbances are advised, especially if there is uncertainty about the size of the fiscal or monetary policy multiplier. 10. What are the relative merits of a cold turkey over a gradualist approach to fight inflation? In your answer discuss the concept of time inconsistency and the importance of credibility. The key question for governments desiring to reduce inflation is how cheaply (in terms of lost output) they can achieve a desired inflation rate. A gradual strategy attempts a slow and steady return to low inflation by reducing monetary growth slowly in an attempt to avoid a significant increase in unemployment. This approach takes a lot longer than the cold-turkey approach that attempts to reduce inflation quickly by immediately and sharply reducing monetary growth. The central question here is how flexible wages and prices are and how fast expectations adjust. With a cold turkey approach, inflation and inflationary expectations will be reduced faster. An increase in the level of unemployment leading to a decrease in the level of output will result in the short run in either case, but the economy will eventually adjust back to the full-employment level of output. The term time inconsistency refers to the problem that the Fed faces when a policy may look appropriate at the time it is announced, but when it is time to execute it, it may no longer look desirable. If the Fed consistently tries to keep inflation under control, even though it may cause some unemployment in the short run, the public will keep inflationary expectations low and is more likely to adjust wage demands downwards. Credibility makes it easier for the Fed to conduct its policies, since the public knows what to expect and will react predictably. For example, if the Fed were to follow a monetary growth rule, then people could more easily anticipate the effects of a disturbance and adjust to it. But if the Fed had a reputation of changing its monetary policy often and unpredictably, its policies might not have the desired effects, since people might not react in the desired way. 11. "A cold-turkey approach is better than a gradualist approach for fighting inflation, since it requires a shorter time to establish a long-run equilibrium at a desired lower inflation rate." Comment on this statement. The gradualist approach lowers money growth over a long period of time to minimize the severity of any resulting recession. The cold-turkey approach achieves the reduction in the inflation rate more quickly, but at the cost of a significant increase in short-run unemployment. Normative considerations determine 117 the relative merits of the two approaches. The cold-turkey approach may benefit from a credibility bonus, since workers and firms do not have to guess whether the government is really committed to lowering the inflation rate. They may therefore reduce their inflationary expectations faster and the economy will adjust back to full-employment much faster. However, if long-term contracts exist, wages and prices cannot adjust quickly and a rapid return to a low-inflation equilibrium at full-employment is fairly unlikely. 12. Comment on the following statement: “Achieving a zero inflation rate by imposing a monetary growth rule will result in more economic stability, a higher growth rate, and a better income distribution.” According to the equation (%∆P) = (%∆M) - (%∆Y) + (%∆V), a zero inflation rate (%∆P) can be easily achieved if monetary growth (%∆M) is kept at a rate equal to the long-term growth rate of real income (%∆Y) adjusted for velocity (%∆V). A monetary growth rule works well if the economy is inherently stable, if most disturbances are small and of short duration, and if velocity is fairly stable or at least predictable. But such a monetary growth rule would tie the central bank's hands if a large disturbance occurred. The cost of long and high unemployment can be very high, especially if wages and prices are fairly rigid. Periods of high and long unemployment particularly affect low-income workers with low skills and therefore the income distribution worsens. While some economists contend that low inflation countries have a higher average economic growth rate, there is no good evidence available for this assertion. 13. Would you support a monetary growth rule that maintains the rate of money supply at 3%, which is slightly higher than the long-term trend of potential output? Why or why not? Explain your answer. The answer to this question is student specific. A student who believes that the economy and velocity are very stable and that disturbances are fairly transitory will probably support such a rule. The argument for such a rule is that it may create more rational expectations in the private sector regarding policy actions by the Fed. Thus, after a disturbance, the private sector would adjust more rapidly and the economy would go back to full employment much more quickly. A student, who believes that disturbances may be persistent, that wages and prices do not adjust rapidly, and that long periods of unemployment are costly, would advocate a more activist approach. This is especially true if velocity is not very stable. Recent experience indicates that a discretionary approach promises more success in keeping the economy close to full employment without causing unacceptable inflation. 14. "Credibility is extremely important in the conduct of monetary policy." Comment on this statement and relate your answer to the concept of dynamic inconsistency. Assume there is a supply shock and the Fed has to decide whether to keep unemployment low by implementing expansionary monetary policy or to concentrate on keeping inflation under control. The dynamic inconsistency approach suggests that the Fed should refrain from a policy response that may look appropriate in the short run but will prove unproductive in the long run. If the Fed always chooses to accommodate a supply shock, people will come to expect such a reaction and will incorporate the 118 assumption of a higher inflation rate in their wage demands. But if the Fed consistently tries to keep inflation under control (even though it may cause some unemployment in the short run), people will lower their inflationary expectations. The Fed will keep its reputation as an inflation fighter, and the economy will adjust back to full employment fairly rapidly. 15. "Policy rules are always preferable to discretionary policy." Briefly comment on this statement. Policy rules predetermine the actions of policy makers and thus eliminate the uncertainty of government actions. This may reduce some of the instability that arises from mistaken expectations. Unfortunately, however, rules do not allow enough flexibility to respond to unforeseen events and cannot accommodate the range of policies required to reduce large and prolonged disturbances. 16. Explain why it is important for the Fed to have credibility in its effort to maintain price stability. Credibility is very important for the Fed, since consistent government actions lead to more accurate private sector expectations. For example, if the Fed were to follow a monetary growth rule, then people could more easily anticipate the effects of a disturbance and could adjust to it. If the Fed consistently tries to keep inflation under control, even though it may cause some unemployment in the short run, people keep their inflationary expectations low and adjust their wage demands downwards. But if the Fed has a reputation of changing its monetary policy often and unpredictably, its policies may not have the desired effects, since people may not react in the desired way. As a result, active monetary policy may actually be destabilizing. 17. "A monetary policy rule is preferable to discretionary stabilization policy." Comment on this statement. In your answer discuss the arguments for and against fine tuning the economy. Policy rules make the actions of policy makers predictable and thus eliminate the uncertainty that comes from unanticipated government actions. They also may reduce instability arising from mistaken expectations. However, rules do not allow flexibility in responding to unforeseen large and prolonged disturbances. Only a very strong proponent of monetarism or the rational expectations approach would propose a strict monetary growth rule. Fine tuning the economy involves the use of policy tools for all (even small) disturbances. But since there are always policy lags and uncertainty about the length of disturbances, fine-tuning may actually be destabilizing. Therefore small policy responses should be undertaken initially and revised later, as more information about the true nature of the disturbance becomes available. 18. "The economy always adjusts back to the full-employment level of output, so policy makers should not be concerned with undertaking active stabilization policy. Instead they should establish more credibility by following a well-defined policy rule." Comment on this statement. Since wages are flexible in the long run, the economy will always eventually adjust back to full employment. According to the Phillips-curve analysis, the economy will be at full employment as long as expected inflation is equal to actual inflation. Therefore, policy makers can create more rational 119 expectations by following a monetary growth rule and announcing its monetary growth targets in advance. In this case, money illusion will not exist and any announced reduction in the growth rate of money supply will lead to lower inflation without much increase in unemployment. But if there is no such rule and the Fed has a reputation of changing its monetary policy often, policies may not have the desired effects, since people may not react in the desired way. It should be noted that an activist monetary growth rule can be designed in which money supply growth changes with changes in the unemployment rate. Fiscal policy rules can also be designed (such as a balanced budget amendment, for example). Whether policy rules actually make sense depends on how fast the economy adjusts back to full employment and how flexible wages and prices are. In the case of large disturbances, rules limit the flexibility of policy makers to respond to a disturbance that may result in a high rate of unemployment. Finally, there are the questions of whether policy rules should be announced in advance and who has the authority to change them if necessary. Finally, if disturbances are perceived to be small it may be better to rely on automatic stabilizers. 120