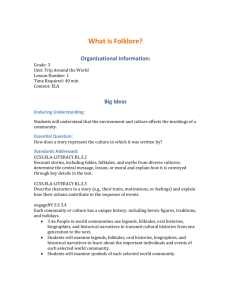

OCR Document - Indiana University

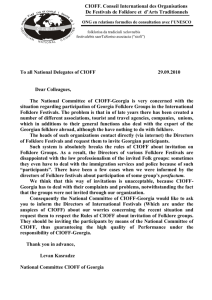

advertisement