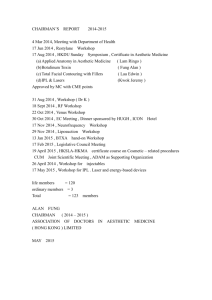

draft august 5, 2014j uly 25, 2014

advertisement