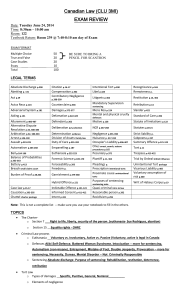

Neutral Principles of Stare Decisis

advertisement