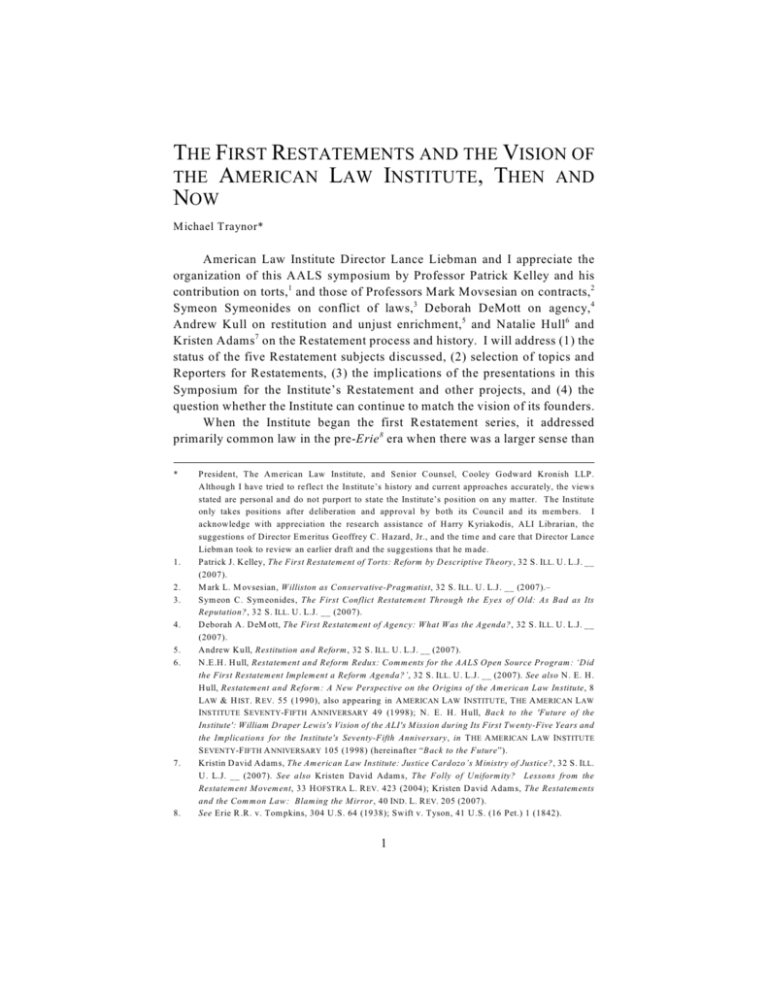

the first restatements and the vision of the american law institute

advertisement

THE FIRST RESTATEMENTS AND THE VISION OF

THE AMERICAN LAW INSTITUTE, THEN AND

NOW

Michael Traynor*

American Law Institute Director Lance Liebman and I appreciate the

organization of this AALS symposium by Professor Patrick Kelley and his

contribution on torts,1 and those of Professors Mark Movsesian on contracts,2

Symeon Symeonides on conflict of laws, 3 Deborah DeMott on agency, 4

Andrew Kull on restitution and unjust enrichment,5 and Natalie Hull6 and

Kristen Adams 7 on the Restatement process and history. I will address (1) the

status of the five Restatement subjects discussed, (2) selection of topics and

Reporters for Restatements, (3) the implications of the presentations in this

Symposium for the Institute’s Restatement and other projects, and (4) the

question whether the Institute can continue to match the vision of its founders.

When the Institute began the first Restatement series, it addressed

primarily common law in the pre-Erie 8 era when there was a larger sense than

*

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

President, The Am erican Law Institute, and Senior Counsel, Cooley Godward Kronish LLP.

Although I have tried to reflect the Institute’s history and current approaches accurately, the views

stated are personal and do not purport to state the Institute’s position on any m atter. The Institute

only takes positions after deliberation and approval by both its Council and its m em bers. I

acknowledge with appreciation the research assistance of H arry Kyriakodis, ALI Librarian, the

suggestions of D irector Em eritus Geoffrey C. H azard, Jr., and the tim e and care that D irector Lance

Liebm an took to review an earlier draft and the suggestions that he m ade.

Patrick J. Kelley, The First Restatem ent of Torts: Reform by D escriptive Theory, 32 S. ILL. U . L.J. __

(2007).

M ark L. M ovsesian, Williston as Conservative-Pragm atist, 32 S. ILL. U . L.J. __ (2007).–

Sym eon C. Sym eonides, The First Conflict Restatem ent Through the Eyes of O ld: As Bad as Its

Reputation?, 32 S. ILL. U . L.J. __ (2007).

D eborah A. D eM ott, The First Restatement of Agency: What Was the Agenda?, 32 S. ILL. U . L.J. __

(2007).

Andrew Kull, Restitution and Reform , 32 S. ILL. U . L.J. __ (2007).

N .E.H . H ull, Restatem ent and Reform Redux: Com m ents for the AALS O pen Source Program : ‘D id

the First Restatement Im plement a Reform Agenda?’, 32 S. ILL. U . L.J. __ (2007). See also N . E. H .

H ull, Restatem ent and Reform : A New Perspective on the O rigins of the Am erican Law Institute, 8

L AW & H IST . R EV. 55 (1990), also appearing in A MERICAN L AW INSTITUTE, T HE A MERICAN L AW

INSTITUTE S EVENTY-F IFTH A NNIVERSARY 49 (1998); N. E. H . H ull, Back to the 'Future of the

Institute': William D raper Lewis's Vision of the ALI's M ission during Its First Tw enty-Five Years and

the Implications for the Institute's Seventy-Fifth Anniversary, in T HE A MERICAN L AW INSTITUTE

S EVENTY-F IFTH A NNIVERSARY 105 (1998) (hereinafter “Back to the Future”).

Kristin D avid Adam s, The Am erican Law Institute: Justice Cardozo’s M inistry of Justice?, 32 S. ILL.

U . L.J. __ (2007). See also Kristen D avid Adam s, The Folly of U niformity? Lessons from the

Restatement M ovem ent, 33 H OFSTRA L. R EV. 423 (2004); Kristen D avid Adam s, The Restatem ents

and the Com m on Law : Blam ing the M irror, 40 IND . L. R EV. 205 (2007).

See Erie R.R. v. Tom pkins, 304 U .S. 64 (1938); Swift v. Tyson, 41 U .S. (16 Pet.) 1 (1842).

1

2

Southern Illinois University Law Journal

[Vol. 32

there is now of a general common law 9 and a clearer slate on which to draw.

During this era and since, the Institute, beginning with its Restatements and

including other projects, has made significant contributions to unifying as well

as simplifying and clarifying the law, primarily (although not exclusively)

state law, as has the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State

Law (NCCUSL),10 through its preparation of uniform laws for consideration

by state legislatures. Today, we have a more complex and challenging

panorama of statutory as well as common law, sophisticated concepts of postErie federalism,11 an important residual area of federal common law, 12 and

developing national and international interests and a foreign relations law.13

The international implications of the law of the United States are growing,

whether that law is federal or state, common law or statute, or regulatory law

of the many administrative agencies, federal, state, and local, that have been

created since the Institute was founded in 1923. Different times produce

different challenges. Expecting the Institute to periodically produce a project

of such dimensions as the first Restatements would be about as fair or realistic

as asking the Supreme Court to periodically produce a case with the

institutional impact of Brown v. Board of Education 14 or Miranda v. Arizona.15

It is fair and realistic to ask, however, if the vision of the Institute continues to

be comparable to that of its founders.

1. THE PRESENT STATUS OF THE FIVE RESTATEMENTS UNDER

DISCUSSION

Torts: Having completed both the Restatement and the Restatement

Second of Torts, the Institute is well underway on the Restatement Third and

has completed the segments on products liability16 and apportionment of

liability17 and virtually completed the segment on torts involving physical

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

See Caleb N elson, The Persistence of G eneral Law , 106 C OLUM . L. R EV. 503 (2006).

For m ore inform ation, see www.nccusl.org (last visited Sept. 25, 2007).

See, e.g., Gasperini v. Ctr. for H um anities, Inc., 518 U .S. 415 (1996); Sem tek Int’l, Inc. v. Lockheed

M artin Corp., 531 U .S. 497 (2001); Alden v. M aine, 527 U .S. 706 (1999); Sem inole Tribe of Fla. v.

Florida, 517 U .S. 44 (1996).

See N elson, supra note 9.

See R ESTATEMENT (T HIRD) OF THE L AW , F OREIGN R ELATIONS L AW OF THE U NITED S TATES (1987;

2 vols).

347 U .S. 483 (1954).

384 U .S. 436 (1966).

R ESTATEMENT (T HIRD) OF T ORTS: P RODUCTS L IABILITY (1998).

R ESTATEMENT (T HIRD) OF T ORTS: A PPORTIONMENT OF L IABILITY (2000).

2007]

The First Restatements

3

harm and property damage.18 It has commenced work on economic torts and

related wrongs. 19 It completed, in a separate Restatement Third of Unfair

Competition, 20 work on a subject that had been addressed in part in the first

Restatement but that was no longer deemed appropriate to include in the

Restatement Second.21

The first Restatement had Francis Bohlen as Chief Reporter, and the

Restatement Second had William Prosser and then, after Prosser’s death, John

Wade as Chief Reporter. One major difference in the Restatement Third is

that the subject of torts has expanded to the point where it is not feasible to

name one person with comparable range, depth of experience, and acuity of

vision to be the Chief Reporter for the entire subject. The Institute necessarily

has had to segment the subject and appoint Reporters for the various segments.

At the same time, it recognizes the need for coordination of the segments and

is therefore beginning the process of overview, liaison, and coordination.22

Contracts: After the first Restatement was published under the

leadership of Chief Reporter Samuel W illiston, two key developments

occurred: Enough progress in the common law occurred to justify a

Restatement Second,23 which had Robert Braucher and then, after his

appointment to the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, Allan

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

R ESTATEMENT (T HIRD) OF T ORTS: L IABILITY FOR P HYSICAL AND E MOTIONAL H ARM , Proposed Final

D raft N o. 1 (A pr. 6, 2005); R ESTATEMENT (T HIRD) OF T ORTS: L IABILITY FOR P HYSICAL AND

E MOTIONAL H ARM ' (Tentative D raft N o. 5, 2007).

R ESTATEMENT (T HIRD) OF E CONOMIC T ORTS AND R ELATED W RONGS '

(D iscussion D raft 2007).

This project began in 2005.

R ESTATEMENT (T HIRD) OF U NFAIR C OMPETITION (1995). AThe chapters (34, 35, 36 and 38) that were

concerned with trade practices and labor disputes have been om itted, in the view that these subjects

have becom e substantial specialties, in their own right, governed extensively by legislation and

largely divorced from their initial grounding in the principles of torts. See pp. 1–3, infra.@

R ESTATEMENT (S ECOND) OF T ORTS '___ (Y EAR). Vol. 4, at vii.

R ESTATEMENT (T HIRD) OF U NFAIR C OMPETITION foreword at xi (1995) (foreword by then D irector

Geoffrey C. Hazard, Jr., stating AThis Restatem ent is the Institute=s first independent work on the

subject. The subject of unfair com petition was to have been addressed in the Restatem ent, Second,

of Torts, as it had been in the original Restatem ent of Torts. H owever, it was eventually decided that

the law of unfair com petition had evolved to the point that it was no longer appropriate to treat it as

a subcategory of the law of Torts. See 4 Restatem ent, Second, Torts, Introduction and Introductory

N ote to Division Nine.@).

U nder the direction of Lance Liebm an, the Institute has begun the necessary coordination efforts.

R ESTATEMENT (S ECOND) OF C ONTRACTS (1981).

4

Southern Illinois University Law Journal

[Vol. 32

Farnsworth,24 as Chief Reporters; and the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC)25

was adopted under the leadership of Chief Reporter Karl Llewellyn 26 and the

joint sponsorship of NCCUSL. As yet, the Institute has not seen a compelling

need to commence work on a Restatement Third. It has, however, worked

with NCCUSL to keep the UCC updated.27 Moreover, after the Institute

disengaged from a proposed Article 2B on software,28 and NCCUSL decided

not to pursue further efforts with its proposed Uniform Computer Information

Transactions Act (UCITA),29 the Institute began an independent project on

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

See E. A LLAN F ARNSWORTH, F ARNSWORTH ON C ONTRACTS (various editions); E. Allan Farnsworth,

Ingredients in the Redaction of the R ESTATEMENT (S ECOND) OF C ONTRACTS (Symposium on the

Restatem ent (Second) of Contracts), 81 C OLUM . L. R EV. 1 (1981); E. Allan Farnsworth, Som e

Prefatory Rem arks: From Rules to Standards (Symposium : The Restatem ent (Second) of Contracts),

67 C ORNELL L. R EV. 634 (1982).

A MERICAN L AW INSTITUTE AND N ATIONAL C ONFERENCE OF C OMMISSIONERS ON U NIFORM S TATE

L AWS, U NIFORM C OMMERCIAL C ODE (1952). The U CC initially included Articles 1 to 10: General

Provisions, Sales, Com m ercial Paper, Bank D eposits and Collections, Letters of Credit, Bulk

Transfers, W arehouse Receipts, Investm ent Securities, Secured Transactions, Effective Date and

Repealer. The code has been am ended m any tim es since 1952.

See Back to the Future, supra note 6, in A MERICAN L AW INSTITUTE, T HE A MERICAN L AW INSTITUTE

S EVENTY-F IFTH A NNIVERSARY at 142–44.

Recent revisions and am endm ents to the U niform Com m ercial Code include: Revised Article 5

(Letters of Credit) (1991–1995); Revised Article 2 (Sales) (1992–1999); Revised Article 8

(Investm ent Securities) (1992–1994); Revised Article 9 (Secured Transactions) (1993–1999);

Am endm ents to Article 7 (Docum ents of Title) (2000–2003). For a recent and im portant perspective,

see Am elia H . B oss, The Future of the U niform Com m erical Code Process in an Increasingly

International World, 68 O HIO S T . L. J. 349 (2007).

A Tentative Draft dated April 15, 1998, was the last form al draft that the Institute issued for proposed

U CC Article 2B. N um erous law review articles exam ined 2B, including: Bryan G. H andlos, D rafting

and N egotiating Com m ercial Software Licenses: A Review of Selected Issues Raised by Proposed

U niform Comm ercial C ode Article 2B, 30 C REIGHTON L. R EV. 1189 (1997); Garry L. Founds,

Shrinkwrap and Clickwrap Agreem ents: 2B or Not 2B?, 52 F ED . C OMM . L.J. 99 (1999); R obert W .

Gom ulkiewicz, H ow Copyleft U ses License Rights to Succeed in the Open Source Software

Revolution and the Implications for Article 2B (Symposium : Licensing in the D igital Age), 36 H OUS.

L. R EV. 179 (1999). At the 1998 ALI Annual M eeting, Professor Charles M cM anis of W ashington

U niversity of St. Louis subm itted a m otion that introduced intellectual property considerations in

relation to m ass-m arket licenses, which resulted in a divided vote against the m otion but ensuing

support for his idea. Charles R. M cM anis, D iscussion of the U niform Com m ercial Code, Article 2B

(Licenses), 75 A.L.I. P ROC. 472–85 (1999); Also in 1998, Professor Pam ela Sam uelson, Director of

the Berkeley Center for Law and Technology, organized an influential conference at Boalt H all

entitled “Intellectual Property and Contract Law in the Inform ation Age: The Im pact of Article 2B

of the U niform Com m ercial Code on the Future of Transactions in Inform ation and Electronic

Com m erce.”

See U CC 2B C onference H om epage, www.law.berkeley.edu/institutes/bclt/

events/ucc2b (last visited June 20, 2007); M ark A. Lem ley, Beyond Preemption: The Law and Policy

of Intellectual Property Licensing, (Sym posium : Intellectual Property and Contract Law for the

Inform ation Age: The Im pact of Article 2B of the U CC on the Future of Inform ation and Com m erce),

87 C AL. L. R EV. 111 (1999) (num erous IP academ ics and practitioners participated in this

sym posium ). The contributions of Professors Sam uelson and M cM anis and other intellectual

property scholars were im portant steps in developing the broader fram ework of understanding that

helped lead to the ultim ate rejection of U CITA. See, e.g., Pam ela Sam uelson, Intellectual Property

and Contract Law for the Information Age: Foreword to a Symposium , 87 C AL. L. R EV. 1 (1999).

C harles R . M cM anis, The Privatization (or “Shrink-Wrapping”) of Am erican Copyright Law , 87

C AL. L. R EV. 173 (1999).

The N ational Conference of Com m issioners on U niform State Laws prom ulgated the U niform

Com puter Inform ation Transactions Act in 1999, but also m ade m inor revisions to it in 2000 and

2002. See http://www.nccusl.org/U pdate/ActSearchResults.aspx (supplying the Act's current status).

At this tim e, M aryland and Virginia are the only states that have adopted U CITA, and in a qualified

m anner at that. Several states have enacted anti-U CITA provisions, including Iowa, N orth C arolina,

W est Virginia and Verm ont. See also Am elia H . Boss, Taking U C ITA on the Road: What Lessons

H ave We Learned?, 7 R OGER W ILLIAMS U . L. R EV. 167 (2001).

2007]

The First Restatements

5

Principles of the Law of Software Contracts,30 with liaison contributions from

a NCCUSL representative.31

Conflict of Laws: Unlike the other Restatements, the first Restatement

of Conflict of Laws, prepared by and under the direction of Chief Reporter

Joseph Beale, sought to freeze the law in notions of territoriality and vested

rights, pursued the bureaucratization and depersonalization of the law with a

vengeance, impeded the development of the law, and further provoked the

conflicts revolution 32 that had already begun and was led and advanced by

noted scholars, including W alter Wheeler Cook,33 David Cavers, 34 Brainerd

Currie, 35 and Robert Leflar, 36 to name just a few. The Restatement Second,

under the leadership of Professor Willis Reese as Reporter, began as the

revolution occurred, was finished in 1971, 37 and, while the revolution

continued its extended and still uncompleted course, was updated in certain

respects in 1988. 38 It enjoys growing acceptance by courts 39 but continues to

receive significant criticism by scholars. 40 Although thoughtful scholars

recommend a Restatement Third,41 the subject is still much debatable, and the

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

The Institute's P RINCIPLES OF THE L AW OF S OFTWARE C ONTRACTS project began in 2004. See

w w w .ali.org/index.cfm ?fuseaction=projects.proj_ip& projec tid=9 (supplying m ore detailed

inform ation).

That representative is currently Professor Boris Auerbach. O ther liaison representatives are Jesse

F e d e r ,

R i c h a r d

L .

F i e l d

a n d

E m e r y

S i m o n .

S e e

www.ali.org/index.cfm ?fuseaction=projects.proj_ip& projectid=9#LIA.

See S YMEON C. S YMEONIDES, T HE A MERICAN C HOICE-OF-L AW R EVOLUTION : P AST , P RESENT AND

F UTURE (2006), reviewed by Louise W einberg, Theory Wars in the Conflict of Laws, 103 M ICH. L.

R EV. 1631 (2005). See also Patrick J. Borchers, The Choice-of-Law Revolution: An Em pirical Study,

49 W ASH. & L EE L. R EV. 357 (1992).

See W ALTER W HEELER C OOK, T HE L OGICAL AND L EGAL B ASES OF THE C ONFLICT OF L AWS (1942);

W alter W heeler C ook, “Substance” and “Procedure” in the Conflict of Laws, 42 Y ALE L. J. 333

(1933); W alter W heeler Cook, The Federal Courts and the Conflict of Laws, 36 U . ILL. L. R EV. 493

(1942).

See D avid F. Cavers, A Critique of the Choice-of-Law Problem , 47 H ARV. L. R EV. 173 (1933); D AVID

F. C AVERS, T HE C HOICE-OF-L AW P ROCESS (1965).

See B RAINERD C URRIE, S ELECTED E SSAYS ON THE C ONFLICT OF L AWS (1963) [hereinafter C URRIE,

E SSAYS]; Brainerd Currie, Notes on M ethods and Objectives in the Conflict of Laws, 1959 D UKE L.J.

171 (1959) [hereinafter Currie, Notes].

See R OBERT A LLEN L EFLAR, L UTHER L. M CD OUGAL, AND R OBERT L. F ELIX , A MERICAN C ONFLICTS

L AW (various editions).

R ESTATEMENT (S ECOND) OF C ONFLICT OF L AWS (1971).

R ESTATEMENT (S ECOND) OF C ONFLICT OF L AWS, 1988 R EVISIONS (1988), issued as perm anent pocket

parts for the two m ain C onflict of Laws volum es.

See, e.g., N edlloyd Lines B.V. v. Superior Court, 834 P.2d 1148 (Cal. 1992); Ingersoll v. Klein, 262

N .E.2d 593 (Ill. 1970); Sym eon C. Sym eonides, The Judicial Acceptance of the Second Conflicts

Restatement: A M ixed Blesssing, 56 M D . L. R EV. 1248 (1997).

See, e.g., W einberg, supra note 32, at 1644–45; Louise W einberg, A Structural Revision of the

Conflicts Restatement, 75 IND . L. J. 475 (2000); Albert A. Ehrenzw eig, The Second Conflicts

Restatem ent: A Last Appeal for Its Withdrawal, 113 U . P A. L. R EV. 1230 (1965); H erm a H ill Kay,

Chief Justice Traynor and C hoice of Law Theory, 35 H ASTINGS L.J. 747 (1984); D avid E. Seidelson,

Interest Analysis or the Restatement Second of Conflicts: Which Is the Preferable Approach to

Resolving Choice-of-Law Problem s?, 27 D UQ . L. R EV. 73 (1988); Larry Kram er, Rethinking Choice

of Law , 90 C OLUM . L. R EV. 277 (1990); Larry K ram er, O n the Need for a Uniform Choice of Law

Code (Sym posium : O ne H undred Years of the U niform State Law s), 89 M ICH. L. R EV. 2134 (1991);

Friedrich K. Juenger, A Third Conflicts Restatem ent?, 75 IND . L.J. 403 (2000) [hereinafter Juenger,

Third Conflicts]; F RIEDRICH K. J UENGER, C HOICE OF L AW AND M ULTISTATE J USTICE (Spec. Ed. 2005)

[hereinafter J UENGER, M ULTISTATE J USTICE]. See also W illiam F. Baxter, Choice of Law and the

Federal System , 16 S TAN . L. R EV. 1 (1963); W illis L. M . Reese, Conflict of Law s and the Restatement

Second, 28 L AW & C ONTEMP . P ROBS. 679 (1963); W illis L. M . Reese, Contracts and the Restatement

of Conflict of Law s, Second, 9 INT 'L & C OMP . L.Q . 531 (1960).

See Gene Shreve, Sym posium , Preparing for the Next Century-A New Restatem ent of Conflicts, 75

IND . L. J. 399 (2000); Sym eon C. Sym eonides, The Need for a Third Conflicts Restatement (And a

Proposal for Tort Conflicts), 75 IND . L. J. 437 (2000); Sym eon C. Sym eonides, Sym posium , Am erican

6

Southern Illinois University Law Journal

[Vol. 32

law in key areas has not sufficiently settled in the view of many to justify

beginning a Restatement Third.42 Three critical building blocks exist in this

area:

(1) Personal jurisdiction is still immersed in fact-intensive concepts of

due process,43 entailing costly and substantial collateral litigation, 44 most

recently in efforts to apply Supreme Court Cases from another era to the

Internet.45

(2) Choice of law is still embroiled in constant debate. 46 Moreover, it is

still limited by the pervasive notion that it is necessary to select the law of a

particular jurisdiction for an issue or a case rather than develop the idea that

choice-of-law cases (at least true conflict cases) are different because by

definition they involve the laws of two or more jurisdictions. The conflict of

laws, especially choice of law, needs more than a tune up; it needs a systematic

overhaul. Although it would be ambitious, I venture to suggest that such an

overhaul of the law of conflict of laws and choice-of-law methodology could,

for example:

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

Choice of Law at the D aw n of the 21 st Century, 37 W ILLAMETTE L. R EV. 1 (2001).

See, e.g., Russell J. W eintraub, The Restatement Third of Conflict of Law s: An Idea Whose Tim e Has

Not Com e, 75 IND . L. J. 679 (2000); Juenger, Third Conflicts, supra note 40.

E.g., International Shoe Co. v. State of W ash., O ffice of Unem ploym ent, 326 U .S. 310, 66 S.Ct. 154

(1945); Shaffer v. H eitner, 433 U .S. 186 (1977); W orldwide Volkswagen Corp. v. W oodson, 444 U .S.

286 (1980); H elicopteros N acionales de Colum ., S.A. v. H all, 466 U .S. 408 (1984); Burger King v.

Rudzewicz, 471 U .S. 462 (1985); Asahi M etal Industry Co. v. Superior Court, 480 U .S. 102 (1987);

Burnham v. Superior Court, 495 U .S. 604 (1990).

U nder the European approach, w hich is m ore rule-oriented, there is less collateral litigation. See

Brussels Regulation on Jurisdiction and Enforcem ent of Judgm ents in Civil and Com m ercial M atters,

EC Regulation N o. 44/2001. See also the predecessor Brussels Convention, officially the

"Convention of 27 Septem ber 1968 on Jurisdiction and the Enforcem ent of Judgm ents in Civil and

Com m ercial M atters" (O fficial Journal L 299, 31/12/1972 pp. 32–42) and the Lugano Convention,

officially the "Convention of 16 Septem ber 1988 on jurisdiction and the enforcem ent of judgm ents

in civil and com m ercial m atters" (O fficial Journal 1988 L 319, p. 9); Linda J. Silberm an,

D evelopm ents in Jurisdiction and Forum Non Conveniens in International Litigation: Thoughts on

Reform and a Proposal for a U niform Standard, 28 T EX. INT. L.J. 501 (1993); See Friedrich K .

Juenger, Am erican Jurisdiction: A Story of Com parative Neglect, 65 U . C OLO . L. R EV. 1 (1993);

Juenger, Third Conflicts, supra note 40; Russell J. W eintraub, D ue Process Lim itations on the

Personal Jurisdiction of State Courts, 63 O R. L. R EV. 485 (1984).

See, e.g., Zippo M anufacturing Com pany v. Zippo D ot Com , Inc., 952 F. Supp. 1119 (W .D .Pa.,

1997); Blum enthal v. D rudge, 992 F. Supp. 44 (D .D .C. 1998). See also Bensusan Restaurant Corp.

v. King, 126 F.3d 25 (CA2 1997); Com puServe, Inc. v. Patterson, 89 F.3d 1257 (6th C ir. 1996);

Cybersell, Inc. v. Cybersell, Inc. et al., 130 F.3d 414 (9th Cir. 1997) Panavision Int'l, L.P. v. Toeppen,

141 F.3d 1316, 1321 (9th Cir. 1998); M ichael Traynor & Laura Pirri, Personal Jurisdiction and the

Internet: Em erging Trends and Future D irections, Practising Law Institute, Sixth Annual Internet

Law Institute, at 93 (2002).

See, e.g., C URRIE, E SSAYS, supra note 35; Currie, Notes, supra note 35; Brainerd Currie, The

D isinterested Third State, 28 L AW & C ONTEMP . P ROBS. 754 (1963); Herm a H ill Kay, A D efense of

Currie=s G overnm ental Interest Analysis, 215 R ECUEIL D ES C OURS 9 (1989); Larry Kram er,

Rethinking Choice of Law , 90 C OLUM . L. R EV. 277 (1990); Louise W einberg, Against Com ity, 80

G EO . L.J. 53 (1991); Joseph W illiam Singer, Real Conflicts, 69 B.U . L. R EV. 3 (1989); Robert Allen

Leflar, Choice-Influencing Considerations in Conflicts Law, 41 N .Y .U . L. R EV. 267 (1966); W illiam

F. Baxter, Choice of Law and the Federal System , 16 S TAN . L. R EV. 1 (1963); H erm a H ill Kay, Kay,

The U se of Com parative Im pairm ent To Resolve True Conflicts: An Evaluation of the California

Experience, 68 C ALIF. L. R EV. 577 (1980); A NDREAS F. L OWENFELD , C ONFLICT OF L AWS: F EDERAL,

S TATE, AND INTERNATIONAL P ERSPECTIVES (2d ed. 1998); Friedrich K. Juenger, H ow D o You Rate

a C entury?, 37 W ILLAMETTE L. R EV. 89 (2001); W illiam L. Reynolds, Legal Process and Choice of

Law , 56 M D . L. R EV. 1371, 1388–89 (1997) (sum m arizing criticism s of Restatem ent Second);

M ichael Traynor, Conflict of Laws, C om parative Law, and the Am erican Law Institute, 49 A M . J.

C OMP . L. 391, 397 (2001). For two key California cases, see Kearney v. Salom on Sm ith Barney, Inc.,

137 P.3d 914 (Cal. 2006); Offshore Rental Co. v. Continental Oil Co., 583 P.2d 721 (Cal. 1978).

2007]

The First Restatements

7

(a) Address and build on the reality that true conflict cases necessarily

involve the laws of two or more jurisdictions and that, as in life, the

appropriate resolution of a conflict is not necessarily limited to one of the

competing choices but may involve an accommodation that takes both choices

into account.47 It is likewise realistic to also recognize that the long effort

during the conflicts revolution and now to perfect a means of choosing a

particular law of a particular jurisdiction is not an attainable quest in true

conflict cases, which by definition are multi-jurisdictional.

(b) Develop the principle, of which Professor Currie was a premier

advocate, of identifying and eliminating “false conflicts” in significant part

through the forum’s restrained and enlightened view of forum law.48

(c) Synthesize and articulate a principle of rational party autonomy for

selecting and interpreting choice-of-law clauses and choice-of-forum clauses

47.

48.

See J UENGER, M ULTISTATE J USTICE, supra note 40, at 9–10:

For our purposes it is im portant to note that the Greeks and the Rom ans approached

the legal issues posed by the cross-frontier m ovem ent of persons, things and

transactions in a sim ilar fashion. Instead of elaborating a system of choice-of-law

rules, they created special tribunals with com petence to decide m ultistate disputes

and accorded them a fair m easure of freedom to find appropriate solutions. Perhaps

in Greece, and certainly in Rom e, these tribunals developed rules of decision that,

although local in origin, had a supranational purport. W hether the reliance on

substantive rules rather than choice-of-law principles to resolve m ultistate problem s

shows a lack of legal acum en or good com m on sense is another question. But if the

experience gathered in antiquity is any indication, choice of law rules in the m odern

sense are clearly not the only possible response to m ultistate problem s.

See also Friedrich K. Juenger, M ass Disasters and the Conflict of Laws, 1989 U . ILL. L. R EV. 105, 126

(Am ost suitable rule of decision”); M ichael Traynor, A H eavenly Inquiry from Professor Juenger, in

F RIEDRICH K. J UENGER, C HOICE OF L AW AND M ULTISTATE J USTICE x1 (Spec. Ed. 2005); additional

references cited at note 61, infra. Cf. Chief Judge Jack W einstein=s creative choice of law

m em orandum in In re “Agent O range” Product Liability Litigation, 580 F. Supp. 690, 711 (E.D .N .Y .

1984) (“no acceptable test can point to any single state”); Id. at 713 (Ait is likely that each of the states

w ould look to a federal or a national consensus law of m anufacturer=s liability, governm ent contract

defense and punitive dam ages. W hat is the nature of the national consensus or federal law is a subject

for another m em orandum ”). Although the case later settled without resolution of the choice-of-law

issues and Chief Judge W einstein=s m em orandum was not an appealable order, on both m andam us

and a later appeal it did not receive the approval of the U .S. C ourt of A ppeals for the Second Circuit.

In re Diam ond Sham rock Chem icals C o., 725 F.2d 858, 861 (2d Cir. 1984); In re “Agent O range”

Product Liability Litigation, 818 F.2d 145, 165 (2d Cir. 1987) (“the intellectual power of Chief Judge

W einstein=s analysis alone w ould not be enough to prevent widespread disagreem ent”). See also Jack

B. W einstein, M ass Tort Jurisdiction and Choice of Law in a M ulti-National World Com m unicating

by Extraterrestrial Satellites, 37 W illam ette L. Rev. 145 (2000).

H ad the first Restatem ent not im peded the developm ent of the law, perhaps a com m on law of conflict

of laws m ight have been developed that decades ago would have begun to yield enough cases

involving relevant elem ents from two or m ore jurisdictions that could then have been synthesized.

It bears noting that the Institute and The International Institute for the U nification of Private Law

(U NIDROIT ) recently published Principles of Transnational Civil Procedure (Cam bridge U . Press,

2006) which synthesizes fundam ental principles of civil procedure from the com m on law system and

the civil law system , in som e respects a far m ore daunting challenge than resolving a conflict between

the laws of two states.

See Currie, supra note 46; Brainerd Currie, M arried W om en=s Contracts: A Study in Conflict-of-Laws

M ethod, 25 U . C HI. L. R EV. 227 (1958). For exam ples of restrained and enlightened decisions, see,

e.g., Lauritzen v. Larsen, 345 U .S. 571 (1953); F. H offm an-La Roche Ltd. v. Em pagran S.A., 542

U .S. 155 (2004); Bernkrant v. Fowler, 55 Cal. 2d 588 (1961). See also W einberg, supra note 32, at

1642; W illiam M . Richm an, D iagram m ing Conflicts: A G raphic U nderstanding on Interest Analysis,

41 O HIO S T . L.J. 317, 318–20 (1982); M ichael Traynor, Professor Currie=s Restrained and

Enlightened Forum , 49 C AL. L. R EV. 845 (1961).

8

Southern Illinois University Law Journal

[Vol. 32

for contract and related disputes, particularly between parties with comparable

bargaining power. 49

(d) Develop additional tools for conflict avoidance, including pretrial

settlement of conflicts issues and alternative dispute resolution.50

(e) Assure a coherent constitutional grounding for a fresh methodology

and make better judicial use of the tools our Constitution provides for our

nation of states in Article IV’s Full Faith and Credit Clause 51 and Privileges

and Immunities Clause;52 Article I’s Commerce Clause;53 and the Fourteenth

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

U .C .C . §§ 1–101 – 1–108 General Provisions (2001 Revisions); See, e.g., N edlloyd Lines B .V. v.

Superior Court, 834 P.2d 1148 (Cal. 1992).

See Jam es A. R. N afziger, Avoidance of Choice-of-Law Conflicts: An Introduction, 12 W ILLAMETTE

J. INT =L L. & D IS. R ESOL. 179 (2004).

U .S. C ONST . art. IV, ' 1. At present, in a true conflict of law s, Athere is no obligation of full faith and

credit to a sister state=s lawsC as opposed to a sister state=s judgm ents.” W einberg, supra note 32, at

1635; see Alaska Packers v. Indus. Accident Com m =n, 294 U.S. 532 (1935); Pac. Em ployers Ins. Co.

v. Indus. Accident Com m =n, 306 U .S. 493 (1939). Com pare H ughes v. Fetter, 341 U .S. 609 (1951);

Carroll v. Lanza, 349 U .S. 408, 411 (AA statute is a >public act= within the m eaning of the Full Faith

and C redit Clause.@). See also W ells v. Sim onds Abrasive Co., 345 U .S. 514, 521 (1953) (Jackson,

J., dissenting) (“The whole purpose and the only need for requiring full faith and credit to foreign law

is that it does differ from that of the forum .”); Kerm it Roosevelt, III, The M yth of Choice of Law:

Rethinking Conflicts, 97 M ICH L. R EV. 2448, 2503–18 (1999); Gene R . Shreve, Choice of Law and

the Forgiving Constitution, 71 IND . L. J. 271 (1996); Robert H. Jackson, Full Faith and CreditC The

Law yers= Clause of the Constitution, 45 C OLUM . L. R EV. 1 (1945).

U .S. C ONST . art. IV, ' 2, cl. 1. See Suprem e Court of N ew Ham pshire v. Piper, 470 U .S. 274 (1985);

H icklin v. O rbeck, 437 U .S. 518 (1978); A ustin v. N ew H am pshire, 420 U .S. 656 (1975); Toom er

v. W itsell, 334 U .S. 385, 395 (1948) (“The prim ary purpose of [the Privileges and Im m unities Clause]

. . . was to help fuse into one N ation a collection of independent, sovereign States.”). Com pare Case

186/187, Cowan v. Tresor Public, 1989 E.C.R. 195 (English resident m ugged on the Paris M etro

entitled to crim e victim com pensation under French law despite its lim itation of coverage to residents

of France; right to travel unencum bered by such residency restrictions was a fundam ental part of

European citizenship) with O strager v. State Bd. of Control, 99 C al. App. 3d 1, 160 Cal. Rptr. 317

(1979), appeal dism issed for want of a substantial federal question, 449 U .S. 807 (1980) (New Y ork

resident shot while on vacation in San Francisco not entitled to crim e victim com pensation under

California law, which, like the French law, was lim ited to residents, because right was not

“fundam ental”). Justice Stevens would have noted probable jurisdiction and set the O strager case for

oral argum ent. Id. See also Q uong H am W ah Co. v. Indus. Accident Com m =n., 192 P.2d 1021

(1920), writ of error dism issed, 255 U.S. 445 (1921) (residency lim itation under California workers=

com pensation law was invalid under Privileges and Im m unities Clause); C URRIE, E SSAYS, supra note

35, at 445–525; Roosevelt, III, supra note 51, at 2471.

U .S. C ONST . art I, '1 Com pare D onald H . Regan, The Suprem e Court and State Protectionism :

M aking Sense of the D orm ant Com m erce Clause, 84 M ICH. L. R EV. 1091 (1986) and Donal H . Regan,

Siam ese Essays: (I) CTS C orp. v. D ynam ics Corp. of Am erican and D orm ant Com m erce Clause

D octrine; (II) Extraterritorial State Legislation, 85 M ICH. L. R EV. 1865 (1987), w ith M ark Gergen,

The Selfish State and the M arket, 66 T EX . L. R EV. 1097 (1988) and M ark Gergen, Territoriality and

the Perils of Form alism , 86 M ICH. L. R EV. 1735 (1988).

2007]

The First Restatements

9

Amendment’s Due Process Clause,54 Equal Protection Clause,55 and Privileges

or Immunities Clause 56 as well as, when appropriate, good legislative use of

Congress’ power to legislate in the area ,57 constitutional tools that are still

relatively unused in the conflict of laws. Reexamination of the constitutional

framework should also lead to an analysis that in addition to interests of

federalism and state autonomy, which the Supreme Court has largely deferred

to, national interests exist and that a national solution may be preferable in

some cases than one that attempts to address a national problem by choosing

the law of one state.58

(f) In considering a national solution to the problem of mass torts,

consider also the recommendations of the American Law Institute in its

Complex Litigation Project.59

(g) Subject to applicable and reexamined constitutional constraints; build

on existing examples of relevant blending techniques, including the principle

of dépeçage,60 which allows a court to apply the law of one state to govern one

54.

55.

56.

57.

58.

59.

60.

U .S. C ONST . am end. XIV, ' 2. See Allstate Ins. Co. v. H ague, 449 U .S. 302, 312–13 (1981); Phillips

Petroleum Co. v. S hutts, 472 U .S. 797, 818 (1985); see also H om e Ins. Co. v. D ick, 281 U .S. 397

(1930); Arthur T. von M ehren & D onald Trautm an, Constitutional Control of Choice of Law: Som e

Reflections on H ague, 10 H OFSTRA L. R EV. 35 (1981); Roosevelt, III, supra note 51, at 2507 (AApart

from the fact that D ue Process governs relations between states and individuals, while Full Faith and

Credit governs interstate relations, there is an im portant conceptual difference. D ue process analysis

sets a m inim um threshold; beyond that threshold there are no restrictions. Consequently, a due

process analysis often leads to the conclusion that a num ber of different states= law s m ay apply. . . .

Full Faith and Credit, by contrast, dem ands that each state accord the greatest degree of respectC full

faith and creditC to the laws of sister states. This m ay be a baseline requirem ent in som e sense, but

the baseline is set as high as it possibly could be. To suppose that such a forceful com m and results

in the sam e threshold test as D ue Process–Cin particular the toothless Allstate testC is to suppose that

the Constitution cares very little about the resolution of conflicts between laws. That supposition is

of course false. . . .”). See also Paul Freund, Chief Justice Stone and the Conflict of Laws, 59 H ARV.

L. R EV. 1210 (1946).

U .S. C ONST . am end. XIV, ' 2. See C URRIE, E SSAYS, supra note 35, at 526–83; D ouglas Laycock,

Equal Citizens of Equal and Territorial States: The Constitutional Foundations of Choice of Law ,

92 C OLUM . L. R EV. 249 (1992), discussed in W einberg, supra note 32, at 1654, note 55 (an im portant

article addressing the problem s of territoriality and intrastate discrim ination and interest analysis and

interstate discrim ination). See also Gergen, Equality and the Conflict of Laws, 73 IOWA L. R EV. 893

(1988).

U .S. C ONST . am end. XIV, ' 2; see Edwards v. California, 314 U .S. 160 (1941).

U .S. C ONST . art. I, ' 1; art. IV, ' 1; am end. XIV, ' 1.

See, e.g., Sam uel Issacharoff, Settled Expectations in a World of U nsettled Law : Choice of Law after

the Class Action Fairness Act, 106 C OLUM . L. R EV. 1839 (2006). Professor Issacharoff is also the

Chief Reporter for the Institute=s current project on Principles of the Law of Aggregate Litigation,

which includes class actions, a subject of crucial relevance to choice-of-law. Professor Issacharoff

identifies the Aneed to facilitate com m on legal oversight of undifferentiated national m arket activity.@

Id.. at 1839. See also Stanley E. Cox, Substantive, M ultilateral, and U nilateral Choice-of-Law

Approaches, 37 W ILLAMETTE L. R EV. 171, 179 (2001) (AThe substantive approach to choice of law

works best in situations where no particular jurisdictions have predom inant sovereignty-based claim s

to adjudicate an underlying dispute, but where m ost parties desire a com prehensive and consistent

result on the m erits . . . . [It] w orks best in m ass disaster and consolidated or class litigation

situations@); Friedrich K. Juenger, M ass Disasters and the Conflict of Laws, 1989 U . ILL. L. R EV. 105,

126 (1989); M ichael H . Gottesm an, D raining the Dismal Swam p: The Case for Federal Choice of

Law Statutes, 80 G EO . L.J. 1 (1991).

A MERICAN L AW INSTITUTE, C OMPLEX L ITIGATION : S TATUTORY R ECOMMENDATIONS AND A NALYSIS

(1994).

See RESTATEMENT ( SECOND) OF C ONFLICT OF LAWS ' 145, cm t. d (1971); D AVID F. C AVERS, T HE

C HOICE-OF-L AW -P ROCESS 19, 34–43 (1965); Courtland H . Peterson, Private International Law at the

End of the Tw entieth C entury: Progress or Regress?, 46 A M . J. C OMP . L. 197, 224–25 (1998); W illis

L.M . Reese, D épeçage: A C om m on Phenom enon in Choice of Law , 73 C OLUM . L. R EV. 58 (1973);

Christopher G. Stevenson, D épeçage: Em bracing Com plexity to Solve Choice-of-Law Issues, 37 IND .

L. R EV. 303 (2003); Louise W einberg, Theory Wars in the Conflict of Laws, 103 M ICH. L. R EV. 1631

(2005). For an international copyright law exam ple, see Itar-Tass Russian N ews Agency v. Russian

10

Southern Illinois University Law Journal

[Vol. 32

issue and the law of another state to govern a separate issue; the developing

theory that substantive principles to resolve conflicts are permissible even if

they are not identical to the law of any competing jurisdiction; 61 the law of

defamation, where the Supreme Court has required and facilitated the blending

of constitutional considerations (such as the First Amendment) with state tort

law;62 and the law of comparative responsibility and apportionment in tort

cases.63

(h) Examine and explain the unique role of judges in conflict of laws

cases, recognizing that judges, whose responsibilities include deciding cases

according to principles that include justice, should not be precluded in

appropriate cases from blending the most fitting or appropriate elements of

competing laws even though the result is not identical to either. Although

legislators constantly blend policies and make compromises, it would be farfetched to contend that judges within applicable constitutional constraints can

never do, even occasionally, what legislators do routinely, particularly when

judges seek to enable sister states to act as sisters and foster an

accommodating, moderate, and not one-sided solution.64

61.

62.

63.

64.

K urier, Inc., 153 F.3d 82, 89–92 (2d Cir. 1998) (ownership question governed by Russian law ,

infringem ent question by U .S. law).

See Paul Schiff Berm an, Judges as Cosm opolitan Transnational Actors, 12 T ULSA J. C OMP . & INT =L.

L. 109, 114 (2004) (Awhereas m ost traditional choice-of-law regim es require a choice of one national

norm , a cosm opolitan approach perm its judges to develop a hybrid rule that m ay not correspond to

any particular regim e@); Hannah L. Buxbaum , Conflict of Econom ic Laws: From Sovereignty to

Substance, 42 V A. J. INT =L. L. 931, 956–63 (2002); Stanley E. Cox, Substantive, M ultilateral, and

U nilateral C hoice-of-Law Approaches, 37 W ILLAMETTE L. R EV. 171, 172–83 (2001); Graem e B.

D inwoodie, A New Copyright O rder: W hy National Courts Should Create G lobal Norm s, 149 U . P A.

L. R EV. 469, 542–79 (2000); Juenger, supra note 46, at 106–07; Friedrich K. Juenger, The Need for

a Com parative Approach to Choice-of-Law Problem s, 73 T UL. L. R EV. 1309, 1317–19 (1999); Luther

L. M cD ougal III, APrivate@ International Law : Just G entium Versus Choice of Law Rules or

Approaches, 38 A M . J. C OMP . L. 521, 536–37 (1990); Peterson, supra note 60, at 214; Traynor, supra

note 48; Arthur T. von M ehren, Special Substantive Rules for M ultistate Problem s: Their Role and

Significance in Contemporary Choice of Law M ethodology, 88 H ARV. L. R EV. 347 (1974); Arthur T.

von M ehren, Choice of Law and the Problem of Justice, L AW & C ONTEMP . P ROBS., Spring 1997, at

27, 38–40. See also John E. Coons, Approaches to Court Imposed Com prom iseC The U ses of D oubt

and Reason, 58 N W . U . L. R EV. 750 (1964); John E. Coons, Com prom ise as Precise Justice, 68 Cal.

L., Rev. 250 (1980).

See, e.g., N .Y . Tim es v. Sullivan, 376 U .S. 254 (1964).

R ESTATEMENT (T HIRD) OF T ORTS: A PPORTIONMENT OF L IABILITY (2000).

See, e.g., Kearney, 137 P.3d 914 ( in which the Suprem e Court of C alifornia held that a California

law prohibiting eavesdropping on telephone conversations justified injunctive relief against future

transgressions: but that the defendant=s reliance on G eorgia law, which did not prohibit the

eavesdropping, precluded m onetary relief for past transgressions. Although phrased in jurisdictionselecting and com parative im pairm ent term s, the result is an exam ple of m ultistate justice worth

building on). See also Berm an, supra note 61, at 110 (Athe best way to avoid legal im perialism is for

judges to think of them selves as cosm opolitan transnational actors@); Traynor, supra note 48.

Judges m ay be required by the Suprem acy Clause to apply a higher law such as a provision of the

Constitution or a federal statute notwithstanding a conflicting state law of the jurisdiction in which

they sit; and they m ay be required by other constitutional clauses or principles of the conflict of laws

that govern in their jurisdiction to apply the law of another state or country. Taking into account and

applying the law s of jurisdictions other than their own, whether vertically or horizontally, is not

m erely an exercise of com ity or discretion but of the responsibilities inherent in judicial office. And

as the Kearney case dem onstrates, judges can select in appropriate cases from provisions of the laws

both of their own jurisdiction and another jurisdiction.

It bears noting that in M atter of Rhone-Poulenc Rorer, Inc., 51 F.3d 1293 (7th C ir. 1995) (Posner, J.),

a divided panel granted a writ of m andam us to require decertification of a class of hemophiliacs who

sought class certification in an action against m anufacturers of anti-hem ophiliac factor concentrate.

The m ajority opinion states that Athe district judge proposes to substitute a single trial before a single

jury instructed in accordance with no actual law of any jurisdictionC a jury that will receive a kind

of E speranto instruction, m erging the negligence standards of the 50 states and the District of

2007]

The First Restatements

11

(i) Reexamine the principle of Klaxon v. Stentor, 65 which constrains the

federal courts from exercising a potentially significant and constructive role

in advancing the rational development of the conflict of laws and suitable

national solutions rather than parochial state solutions for national issues.66

(k) Take into appropriate account the growing and relevant international

efforts such as those to achieve harmonization of the law;67 international

65.

66.

67.

Colum bia.@ Id. at 1300. The m ajority also referred to Athe questionable constitutionality of trying

a diversity case under a legal standard in force in no state,@ although the court noted that a sim ilar

approach Ahas been approved for asbestos litigation.@ Id. at 1304. The panel m ajority recognized that

Aat som e level of generality the law of negligence is one, not only nationwide but worldwide,@ but also

stated that negligence law can differ am ong the states on such issues, for exam ple, as duty of care,

forseeability, proxim ate cause, and judicial form ulations of pattern jury instructions. Id. Although

Judge Posner=s rem arks about AEsperanto@ and possible unconstitutionality m ight be read m ore

broadly, it is crucial to note that they arose in the specific context of a class action involving the

possible blending in a jury instruction of the law of 51 jurisdictions. By contrast, in typical choice-oflaw cases, there are both historical roots and theoretical justifications for blending the laws of two or

m ore jurisdictions. See, e.g., supra notes 46 and 59. Indeed, it seem s doubtful that the disparaging

term s, Ano actual law,@ or AEsperanto,@ or Aquestionable constitutionality,@ could be applied rationally,

for exam ple, to the law of defam ation, or determ inations of com parative responsibility, or various

and num erous statutes, which often blend and com prom ise various com peting interests, or to cases

such as the recent Suprem e Court of C alifornia=s decision, which invoked California law to justify

injunctive relief but Georgia law to deny m onetary relief. Kearney, 137 P.3d 914.

M oreover, in m any, if not m ost, true conflict cases, there will be som e plausible rationale that will

allow the court to choose the law of either State A or State B to resolve the case or question. If, for

exam ple, the forum is State A, and it could perm issibly choose the law of either A or B, what is the

problem with the court=s choosing to apply State A=s law to a part of the case and State B=s law to the

rest? Instead of disregarding entirely the law of one interested state, the court seeks to balance the

interests of each state. See D inwoodie, supra note 61, at 546 (AB ut the critique is som ewhat less

withering when the state in question freely decides that it wishes Esperanto to be the vernacular of

choice@); id. at 576: A[T]he approach that I propose can be no m ore offensive to national sovereignty

than the wholesale application of foreign law. If it is consistent with our existing notions of judicial

duty either to apply the forum law or the law of another state, the application of a law falling between

that of the forum and the other state cannot be m ore offensive to notions of dem ocratic legitim acy or

state sovereignty@). See also Alfred H ill, The Judicial Function in Choice of Law , 85 C OLUM . L. R EV.

1585 (1985) (providing an earlier and thoughtful view, although a m ore conservative one).

13 U .S. 487 (1941).

See H enry M . H art, Jr., The Relations Between State and Federal Law , 54 C OLUM . L. R EV. 489, 513

(1954); Issacharoff, supra note 58, at 1841–42, 1851–57, 1865; Roosevelt, III, supra note 51, at 2510

n. 264 (AI do not believe that federal conflicts rules are necessary, provided that we pay attention to

constitutional restrictions on state conflicts rules. It is troubling that under K laxon the federal courts

act as ventriloquists= dum m ies, reproducing the very parochialism and bias their diversity jurisdiction

exists to counter@).

See, e.g., H annah Buxbaum , Conflict of Econom ic Law s: From Sovereignty to Substance, 42 V A. J.

INT =L L. 931, 947–50 (2002); Dinwoodie, supra note 61, at 570 n. 318.

Traditionally, choice of law and harm onization are cast as alternative m eans of

accom m odating international differences. Choice of law analysis involves difficult

decisions w here harm onization has failed to eradicate differences in national laws;

harm onization of national laws reduces the im portance of choice of law determ inations

where those determ inations have becom e too troublesom e or uncertain. The latter

observation explains in part the recent explosion in copyright harm onization efforts. But

the substantive law m ethod would enlist one strategy in the cause of the other, by

facilitating the convergence of different national rules applicable to international disputes.

See also A MERICAN L AW INSTITUTE, INTELLECTUAL P ROPERTY : P RINCIPLES G OVERNING

J URISDICTION , C HOICE OF L AW , AND J UDGMENTS IN T RANSNATIONAL D ISPUTES, Tentative

D raft N o. 1 (2007); Paul Schiff Berm an, Tow ards a Cosmopolitan Vision of Conflict of

Law s: Redefining G overnm ental Interests in a G lobal Era, 153 U . P A. L. R EV. 1819

(2005); Paul Schiff Berm an, The G lobalization of Jurisdiction, 151 U . P A. L. R EV. 311

(2002); Christian Joerges, The Challenges of Europeanization in the Realm of Private

Law : A Plea for a New Legal D iscipline, 14 D UKE J. C OMP . & INT =L L. 149 (2004).

12

Southern Illinois University Law Journal

[Vol. 32

cooperation and coordination mechanisms as in international insolvency law,68

and international intellectual property law; 69the articulation of international

principles as in UNIDROIT’s Principles of International Commercial

Contracts,70 which are akin to the Restatements;71 and the emergence of a lex

mercatoria.72 It is not a coincidence that in contrast to our aggressive term,

“the conflict of laws,” other countries use the more peaceful term, “private

international law.” 73

(3) Only the third building block of judgments is relatively coherent, as

it is governed by a principle of finality. 74 Even with judgments, however,

emerging issues exist about whether and to what extent to recognize and

enforce non-monetary judgments.75

The Institute is not ignoring conflict of laws. So far, it has addressed it

in discrete ways, especially through its now-completed project on recognition

and enforcement of foreign country judgments;76 its almost-completed project

on international intellectual property;77 and its work with NCCUSL on

68.

69.

70.

71.

72.

73.

74.

75.

76.

77.

See A MERICAN L AW INSTITUTE, T RANSNATIONAL INSOLVENCY P ROJECT : C OOPERATION A MONG THE

N AFTA C OUNTRIES (2003) (the pioneering work); see also A NNE-M ARIE S LAUGHTER , A N EW W ORLD

O RDER (2004); Buxbaum , supra note 67, at 950–53; Hannah Buxbaum , Forum Selection in

International Contract Litigation: The Role of Judicial D iscretion, 12 W ILLAMETTE J. INT =L L. &

D ISP . R ESOL. 185 (2004); E. Bruce Leonard, Breakthroughs in Court-to-C ourt Com m unications in

Cross-Border C ases, 20 A M . B ANKR. INST . J. 18 (Sept. 2001); E. Bruce Leonard, The Way Ahead:

Protocols in International Insolvency Cases, 17 A M . B ANKR. INST . J. 12 (Jan. 1999); N afziger, supra

note 50, at 181–82; Anne-M arie Slaughter, Focus: Em erging Fora for International Litigation (Part

2): A G lobal Com m unity of Courts, 44 H ARV. INT =L L. J. 191 (2003); Jay Lawrence W estbrook, The

Transnational Insolvency Project of the Am erican Law Institute, 17 C ONN. J. INT =L L. 99 (2001); Jay

Law rence W estbrook & Jacob S. Ziegel, The Am erican Law Institute NAFTA Insolvency Project, 23

B ROOK. J. INT = L 7 (1997); Jay Lawrence W estbrook, Theory and Pragm atism in G lobal Insolvencies:

Choice of Law and Choice of Forum , 65 A M . B ANKR. L.J. 457 (1991). In cooperation with the

International Insolvency Institute, the ALI has recently begun a new transnational insolvency project

on Principles of C ooperation (2006–).

A MERICAN L AW INSTITUTE, INTELLECTUAL P ROPERTY , supra note 67.

U N ID RO IT, Principles of International Com m ercial Contracts, 34 L.L.M . 1067 (1995); see M ICHAEL

J OACHIM B ONELL , A N INTERNATIONAL R ESTATEMENT OF C ONTRACT L AW (2d ed. 1997).

See Bonell, supra note 70; Juenger, supra note 61.

See Juenger, supra note 61, at 1318–19, 1330; Friedrich K. Juenger, Am erican Conflicts Scholarship

and the New Law M erchant, 28 V AND . J. T RANSNAT =L L. 487, 490–92 (1995). But see Keith H ighet,

The Enigm a of the Lex M ercatoria, 63 T UL. L. R EV. 613 (1989).

See C HESHIRE & N ORTH, PRIVATE INTERNATIONAL LAW (13th ed. 1999). See also Friedrich K.

Juenger, supra note 61; Sir Basil M arkesinis & Jorg Fedtke, The Judge as C om paratist, 80 T UL. L.

R EV. 11 (2005); M ilena Sterio, The G lobalization Era and the Conflict of Laws: What Europe Could

Learn from the U nited States and Vice Versa, 13 C ARDOZO J. INT =L & C OMP . L. 161 (2005); M ichael

Traynor, Conflict of Laws, C om parative Law, and the Am erican Law Institute, 49 A M . J. C OMP . L.

391, 395–97, 400–02 (2001). Although developing international principles are im portant and

relevant, international conflicts and dom estic conflicts are different under the Constitution of the

U nited States. See Albert A. Ehrenzw eig, Interstate and International Conflicts Law: A Plea for

Segregation, 41 M INN . L. R EV. 717 (1957).

See, e.g., Baker v. Gen. M otors Corp., 522 U .S. 222 (1998); Fauntleroy v. Lum , 210 U .S. 230 (1908).

Baker, 522 U .S. 222. See also A MERICAN L AW INSTITUTE , R ECOGNITION AND E NFORCEMENT OF

F OREIGN J UDGMENTS: A NALYSIS AND P ROPOSED F EDERAL S TATUTE 3 (2006).

A MERICAN L AW INSTITUTE, R ECOGNITION AND E NFORCEMENT OF F OREIGN J UDGMENTS: A NALYSIS

AND P ROPOSED F EDERAL S TATUTE (2006); Linda Silberm an, Com parative Jurisdiction in the

International Context: Will the Proposed H ague Judgm ents Convention Be Stalled?, 52 D EP AUL L.

R EV. 319 (2002); Linda Silberm an, Can the H ague Judgments Project Be Saved?: A Perspective from

the U nited States, in A G LOBAL L AW OF J URISDICTION AND J UDGMENTS: L ESSONS F ROM THE H AGUE

158, 158–89 (2002); Linda J. Silberm an & Andreas F. Lowenfeld, A D ifferent Challenge for the ALI:

H erein of Foreign Country Judgm ents, an International Treaty and an Am erican Statute, 75 IND . L.J.

635, 635–38 (2000).

A MERICAN L AW INSTITUTE, INTELLECTUAL P ROPERTY : P RINCIPLES G OVERNING J URISDICTION ,

C HOICE OF L AW , AND J UDGMENTS IN T RANSNATIONAL D ISPUTES (Proposed Final D raft 2007).

2007]

The First Restatements

13

amendments to the choice of law provisions of Article 1 of the UCC,78 an

effort that unfortunately has not met with enactments by state legislatures. Its

work on world trade 79 is also relevant because trade disputes often involve

conflicting laws and policies that may need both harmonization as well as a

means for resolving conflicts.

Agency: The first Restatement was succeeded by a Restatement

Second,80 which has just recently been succeeded by the Restatement Third,

under the leadership of Chief Reporter Deborah DeMott.81 It addresses central

and modern problems of liability and attribution of responsibility in

challenging situations such as those presented by the Enron disaster. 82 It should

prove to be of great help to courts and lawyers who must wrestle with these

ubiquitous problems and to scholars who write about them.

Restitution and Unjust Enrichment: The first Restatement,83 which did

not include Unjust Enrichment in its title although it addressed that principle

throughout, was a pioneering work. It was followed by an effort, eventually

terminated, to begin a Restatement Second 84 and then by the current project,

the Restatement Third of Restitution and Unjust Enrichment, 85 under the

leadership of Chief Reporter Andrew Kull.86 In an elegantly stated and deeply

78.

79.

80.

81.

82.

83.

84.

85.

86.

U .C.C. Art. 1 (General Provisions) (2001 Revisions). The A rticle 1 am endm ents addressed only

choice of law clauses, not choice of forum clauses because the D rafting Com m ittee wanted to avoid

situations in which one party of an entirely dom estic transaction would choose, due to its superior

bargaining power, not a fellow state, but instead a foreign state with such fundam entally different

policies that such forum selection would be overreaching.

The Institute began a project entitled “Principles of W orld Trade Law: The W orld Trade

O rganization” in 2001. See infra text accom panying notes 122–27.

R ESTATEMENT (S ECOND) OF A GENCY (1958).

R ESTATEMENT (T HIRD) OF A GENCY (2006). See also D eborah A. D eM ott, When Is a Principal

Charged with an Agent's Know ledge? (Com parisons and Connections: A Symposium in M emory of

H erbert Bernstein), 13 D UKE J. C OMP . & INT 'L L. 291 (2003); D eborah A. D eM ott, A Revised

Prospectus for a Third Restatem ent of Agency, 31 U.C. D AVIS L. R EV. 1035 (1998).

In the winter of 2001–02, W illiam Powers, Jr., then D ean of The U niversity of Texas School of Law

(and now President of the University of Texas), chaired the Internal Com m ittee of Investigation for

Enron. Com m issioned by the Enron Board of D irectors, this com m ittee investigated the transactions

between Enron and several partnerships headed by Enron=s form er chief financial officer Andrew

Fastow. That investigation led to the APowers Report,@ which was highly critical of these transactions.

R ESTATEMENT OF R ESTITUTION (1933).

Two Tentative drafts were produced in the early 1980s for the Restatem ent of the Law Second,

Restitution, before the project was discontinued. In Tentative D raft N o. 1 (1983), a proposed section

6, entitled “Benefit in Relation to an Agreem ent,” provided in subdivision (2) that “A person whose

conduct in negotiating for a gain or advantage results in a benefit to him and a loss or expense to

another m ay be unjustly enriched by the benefit, if, in the absence of com pensation to the other, the

conduct appears unconscionable in purpose or effect. N o account is taken of uncom pensated loss or

expense in this connection if it results from a risk fairly chargeable, as between the parties, to the

person who bears it. Such loss or expense is taken into account only if it w as foreseeable by the

person receiving the benefit” provided. H ad such a principle, which was controversial, been adopted,

it m ight have led to the developm ent of the law of restitution and unjust enrichm ent in this troubled

area akin to that under section 90 of the first Restatement and Restatem ent Second of Contracts. The

Restatem ent Third does not adopt this proposal but addresses the problem s in other ways. For

exam ple, it discusses anticipated contracts that fail to m aterialize in Section 23, com m ent c, and

“opportunistic” behavior in Section 39.

The Third Restatement of Restitution and U njust Enrichm ent project has been underway since 1997

and has thus far produced five Tentative Drafts and num erous Prelim inary and C ouncil D rafts.

See Andrew Kull, Rescission and Restitution, 61 B US . L AW . 569 (2006); Andrew Kull, Jam es Barr

Am es and the Early M odern H istory of U njust Enrichment, 25 O XFORD J. L EGAL S TUD . 297 (2005);

Andrew Kull, Sym posium , The Source of Liability in Indemnity and Contribution, 36 L OY . L.A. L.

R EV. 927 (2003); Andrew Kull, Sym posium , Restitution's Outlaws, 78 C HI.-K ENT L. R EV. 17 (2003);

Andrew Kull, D efenses to Restitution: The Bona Fide Creditor, 81 B.U . L. R EV. 919 (2001); Andrew

Kull, Sym posium , D isgorgement for Breach, The “Restitution Interest,” and The Restatement of

Contracts, 79 T EX . L. R EV. 2021 (2001); Andrew Kull, Restitution in Bankruptcy: Reclam ation and

14

Southern Illinois University Law Journal

[Vol. 32

researched project, and in various tentative drafts that have been discussed and

largely approved by the Institute’s Council and members, Professor Kull

articulated substantive principles of liability, some such as mistakes that

constitute a basis for liability independent of tort and contract,87 and some that

provide alternative grounds for liability. 88 He now begins the challenging task

of articulating the various remedies, including not only monetary relief and the

constructive trust but others such as the equitable lien and subrogation. When

completed, this project will not only clarify and simplify a major area of the

common law; it also will provide another important way of looking at cases

that involve an element of unjust enrichment.

II. SELECTION OF TOPICS AND REPORTERS FOR

RESTATEMENTS

In contrast to the first Restatement era, the Institute now exercises more

choices about the form and approach that a project takes. The main choices

are a Restatement, model legislation, or a set of Principles. It also may

sponsor studies “for” the Institute rather than by it, as in the enterprise liability

project that preceded the Restatement Third of Torts: Products Liability.89

Under the leadership of Conrad Harper, Chair of the Institute's Special

Committee on Institute Style, and Michael Greenwald, Reporter (and then also

a Deputy Director), in 2005 the Institute issued a handbook for Institute

Reporters and those who review their work, which is entitled Capturing the

Voice of The American Law Institute.90 The Handbook describes the various

forms and articulates the differences among Restatements,91 Legislative

Recommendations,92 Principles, 93 and Studies. 94 Those distinctions are

pertinent to the decision about what form a project should take.

87.

88.

89.

90.

91.

92.

93.

94.

Constructive Trust, 72 A M . B ANKR. L.J. 265 (1998); Andrew Kull, Rationalizing Restitution, 83 C AL.

L. R EV. 1191 (1995); Andrew Kull, Restitution as a Rem edy for B reach of Contract, 67 S. C AL. L.

R EV. 1465 (1994).

See R ESTATEMENT OF R ESTITUTION AND U NJUST E NRICHMENT §§ 5–12 (Tentative D raft N o. 1, 2001).

Tentative D raft N o. 4 outlines the scope of the project and includes sections on defective consent or

authority ('' 13–17); transfers under legal com pulsion ('' 18–19); intentional transactions (''

20–30); restitution and contract ('' 31–39); restitution for wrongs ('' 40–46); and indirect

enrichm ent ('' 47–48). R ESTATEMENT OF R ESTITUTION AND U NJUST E NRICHMENT §§ 13–49

(Tentative D raft N o. 4, 2001).

A MERICAN L AW INSTITUTE, E NTERPRISE R ESPONSIBILITY FOR P ERSONAL INJURY (1991).

A MERICAN L AW INSTITUTE, C APTURING THE V OICE OF T HE A MERICAN L AW INSTITUTE: A H ANDBOOK

FOR ALI R EPORTERS AND T HOSE W HO R EVIEW T HEIR W ORK (2005).

ARestatem ents are addressed to courts and others applying existing law. Restatem ents aim at clear

form ulations of com m on law and its statutory elem ents or variations and reflect the law as it presently

stands or as it m ight plausibly be stated by a court. Restatem ent black letter form ulations assum e the

stance of describing the law as it is.@ H ANDBOOK , supra note 90, at 4.

AM odel or uniform codes or statutes and other statutory proposals are addressed m ainly to

legislatures, with a view toward legislative enactm ent. Statutory form ulations assum e the stance of

prescribing the law as it shall be.@ Id. at 10.

A Principles m ay be addressed to courts, legislatures, or governm ental agencies. They assum e the

stance of expressing the law as it should be, which m ay or m ay not reflect the law as it is.@ Id. at 12.

“The Institute som etim es produces studies that analyze in depth particular areas of the law. . . . [These

studies m ay lay] the practical and theoretical groundwork for subsequent black-letter propositions.@

Id. at 14.

2007]

The First Restatements

15

The Institute is not precluded from other approaches. For example, in

1945, it published a draft Statement of Essential Human Rights,95 not as an

official work of the Institute itself that carries with it the imprimatur of

approval by both the Council and the members, but as a contribution to the

debate, one that was drafted by a Committee representing principal cultures of

the world appointed by the Institute and that played a major role in what

became the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was adopted by the

General Assembly of the United Nations in 1947.96 This might be a good time

for the Institute to consider other areas of law where our work would seek to

contribute to enlightenment and debate rather than to articulating definitive

legal principles. Such areas might include questions concerning the challenges

of wealth transfer across generations; issues at the intersection of science and

law; new thinking about the imperfectly restated subject of conflict of laws,

discussed supra; or proposing a model cross-national license for intellectual

property.97

A major criterion is whether a project will contribute to the general law,

including both common law and statutory law. Two recent examples of

projects that synthesize common law and statutory law are the Restatement

Third of Property: Wills and Other Donative Transfers,98 which synthesizes

various state statutes such as the Uniform Probate Code 99 and the common law,

and the Restatement Third of Unfair Competition, which synthesizes federal

statutory law, such as the Lanham Act on trademarks, 100 and state statutory

law, such as the Uniform Trade Secrets Act,101 and the common law.102

95.

S TATEMENT OF E SSENTIAL H UMAN R IGHTS (1945). The Statem ent was form ally published by

Am ericans U nited for W orld O rganization, Inc. The com plete text of the Statem ent of Essential

H um an Rights appears in A MERICAN L AW INSTITUTE, T HE A MERICAN L AW INSTITUTE S EVENTYF IFTH A NNIVERSARY (1998), at 261. See also H ull, supra note 6, at 105, 141–42; M ichael Traynor,

The President’s Letter “That’s Debatable”: The ALI as a Public Policy Forum : Ninth in an

O ccasional Series: The Statem ent of Essential H um an Rights— A G roundbreaking Venture (pts. 1 &

2), T HE ALI R EPORTER (ALI Phila., Pa.), W inter 2007, at 1, T HE ALI R EPORTER (ALI Phila., Pa.),

Spring 2007, at 1.

96. U niversal D eclaration of H um an Rights, G.A. res. 217A, at 71, U .N . GAO R, 3d Sess., 1st plen. m tg.,

U .N. Doc A/810 (D ec. 12, 1948).

97. At an early m eeting that helped fram e what becam e the Institute=s project on International Intellectual

Property, a suggestion was m ade, to m y recollection by then D irector Geoffrey C. H azard, Jr., that

am ong the array of alternatives, a possible project m ight be the articulation of a m odel license of

intellectual property, with principal negotiating alternatives and com m ents. There m ay be other

negotiating situations in which it could be useful to identify the m ajor alternative solutions.

98. R ESTATEMENT (T HIRD) OF P ROP .: D ONATIVE T RANSFERS (2003).

99. U NIFORM P ROBATE C ODE (am ended 2006).

100. 15 U .S.C. '' 1051–29 (2000).

101. The N ational Conference of Com m issioners on U niform State Laws prom ulgated the Uniform Trade

S e c r e t s A c t i n 1 9 7 9 , w i th a n a m e n d e d v e r s i o n i s s u e d i n 1 9 8 5 .

See

www.nccusl.org/Update/uniform act_factsheets/uniform acts-fs-utsa.asp (last visited Sept. 25, 2007)

(the Act's current status).

102. Chapter fourteen states the principles governing liability for the appropriation of intangible trade

values. Topic 1 states a general rule rejecting the recognition of exclusive rights in intangible trade

values, subject to a series of specified exceptions. R ESTATEMENT (T HIRD) OF U NFAIR C OMPETITION

§ 38 (1995). Topic 2 states the rules com prising the law of trade secrets. A m ajority of the states

have adopted the U niform Trade Secrets Act, which codifies the com m on law doctrines relating to

the protection of trade secrets. The rules stated in Topic 2 are applicable to both statutory and

com m on law trade secret cases. Id. at §§ 39–45. Rules governing the right of publicity, which

protects against certain appropriations of the com m ercial value of a person's identity, are treated in

Topic 3. Id. at §§ 46–49.

16

Southern Illinois University Law Journal

[Vol. 32

The Institute takes into account the “rules v. standards” debate.103 A

subject matter that is quite developed in case law and statutes may be ready for

Restatement treatment and the articulation of black letter “rules.” One that is

not yet so developed may be appropriate for Principles treatment and the

articulation of principles, sometimes accompanied by “standards” and tests

that include several factors. The difference is only suggestive, not operative.

For example, a Restatement provision may be stated in terms of various

general factors as is the test of a “most significant relationship” in section 6 of

the Restatement Second of Conflict of Laws.104

In addition to the distinctions in the form of a project, other criteria that

are relevant to the decision whether the Institute will undertake a project in any

form can be articulated in the form of questions: Can the Institute contribute

to bringing reason and order to a particular area of law? Will the project be

useful to judges, practitioners, and teachers? Can it identify an able Reporter?

Criteria for the selection of an able Reporter include mastery of the

subject matter; leadership qualities; standing among peers, although not

necessarily eminence (Beale after all was eminent but wrong); writing ability;

being able to take and commit the time necessary to prepare drafts and to see

the project through to publication; and the ability to listen to and respect the

views of others, while not necessarily agreeing with them.

It may be useful to provide potential examples without extended

discussion: Examples of projects that are eligible presently for Restatement

treatment in my view include employment law (which the Institute has begun

to address in Restatement form),105 although controversial;106 the law of expert

evidence; medical malpractice; and the law of remedies, particularly in torts.

Examples of projects that are not eligible presently for Restatement treatment

103. See Louis K aplow, Rules Versus Standards: An Econom ic Analysis, 42 D UKE L. J. 557 (1992);

Antonin Scalia, The Rule of Law as Law of Rules, 56 U . C HI. L. R EV. 1175 (1989); Cass R. Sunstein,

Problem s with Rules, 83 C AL. L. R EV. 953 (1995); M ichael Traynor, Public Sanctions, Private

Liability, and Judicial Responsibility, 36 W ILLAMETTE L. R EV. 787, 803–04 (2000):

C ourts face a fam iliar dilem m a when fashioning judicial rules: W hether cases and

statutes have developed sufficiently to support a court=s articulation of a rule, or

whether the law rem ains sufficiently uncertain that a court is m ore com fortable

continuing to apply m ultiple standards or factors to particular situations. . . . The

choice between rules, standards, m ultiple factors, principles, or other approaches

presents a constant challenge to courts and legislatures as well as to the ALI, whose

founding purpose is to contribute to >the clarification and sim plification of the law.=

U nlike a trial or appellate court, confronted with one case to decide, the ALI has the

opportunity to consider a variety of decided cases and enacted statutes, as well as the

challenge and responsibility to synthesize them .

104. R ESTATEMENT (S ECOND) OF C ONFLICT OF L AWS § 6 (1971). See, e.g., Traynor, supra note 103, at

803 n. 89 (2000) (A[t]he conflict of law s provides one of the best exam ples of courts struggling to

reach the proper balance between factors and rules@); id. at 804 (Restatem ent Second of Conflict of

Law s, section 6, Alists seven factors >relevant to the choice of the applicable rule of law,= which

include >the needs of the interstate and international system s.= H ow is a trial court going to apply that

test? Is it susceptible of proof by evidence? Should the court seek learned am icus briefs on the

point?)@.

105. The Em ploym ent Law project so far has produced num erous confidential Prelim inary and Council

D rafts, as well as one D iscussion D raft, dated April 27, 2006. R ESTATEMENT OF EMPLOYMENT

(D iscussion D raft N o. 1, 2006).

106. See, e.g., M atthew W . Finkin, Shoring up the C itadel (At-Will Em ploym ent), 24 H OFSTRA L AB . &

E MP . L. J. 1 (2006); M atthew W . Finkin, Second Thoughts on a Restatement of Em ployment Law , 7

U . P A. J. L AB . & E MP . L. 279 (2005).

2007]

The First Restatements

17

in my view include information liability, which is too undeveloped; 107 personal

jurisdiction and choice of law, which are still too unsettled and need a fresh

look;108 and environmental law, which entails an intertwining of complex

statutory laws and administrative regulations, federal and state, and local land

use laws.109

III. IMPLICATIONS FOR THE FUTURE, AND THE VISION OF THE

INSTITUTE

The Institute’s strengths are its members and its deliberative processes,

stature, independence, and dedication to quality. Its resources are limited. It

must decide carefully what projects are fitting. It will want to undertake

projects that meet the needs of the profession and the public. It can find a

medium ground for solid work between stultifying description of the “is” and

unduly venturesome pursuit of the “ought.” Its work need not be pigeonholed

as either “descriptive”or “normative.” It can identify and pursue work that has

a reasonable shelf life and that will be useful for a generation or more.

In reflecting on the presentations to this Symposium and the

contributions of the first Restatement series as a whole, it is evident that the

founders of the Institute and the leaders who saw the first Restatements

through to publication had an important and useful, although not flawless,

vision, one of restating the law of the United States in the areas that covered