JBR-07929; No of Pages 11

Journal of Business Research xxx (2013) xxx–xxx

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Business Research

How balance theory explains high-tech professionals' solutions of enhancing

job satisfaction

Man-Ling Chang a,⁎, Cheng-Feng Cheng b,⁎⁎

a

b

Asia University, Department of Leisure and Recreation Management, Taiwan

Asia University, Department of International Business, Taiwan

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 1 August 2013

Received in revised form 1 October 2013

Accepted 1 October 2013

Available online xxxx

Keywords:

Autonomy

Balance theory

Leader–member exchange

Managerial control

Work–family conflict

a b s t r a c t

R&D professionals in high-tech industries often face struggles between the work and family domains. Additionally,

the job autonomy is an essential antecedent of being a professional, whereas a R&D manager determines the

subordinates' job autonomy, helps mitigate their work–family conflict and contributes their innovativeness.

Accordingly, the R&D employee, supervisor, job autonomy, and family which form a tetragonal-relationship

system are the major entities in the R&D employee's cognitive structure. The R&D employee's and supervisor's

perceptions about other entities are regarded as the connections among entities and stand for the concepts of

leader–member exchange, self-determination (i.e., perceptions about job autonomy), managerial control (related

to autonomy support), work–family conflict, and managerial work–family support. Although prior studies indicate

individual influences of these concepts on the job satisfaction, they neglect the combined influences. This study applies the balance theory to explore how R&D professionals balance these connections in their cognitive structure

for achieving the high job satisfaction. Among 32 possible combinations of factors, this study identifies four causal

conditions for the high job satisfaction and indicates the best and worst conditions. The findings inform implications to manage R&D professionals.

© 2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Employees often face struggles between work and family domains.

Such struggles are particularly obvious for R&D employees in hightech industries due to highly demanding works and their professional

roles. On one hand R&D employees who occupy work roles may experience work–family conflict (Lee, 2008), and on the other they are professionals with the necessary knowledge and skills and thus require more

autonomy than other employees (Farr-Wharton, Brunetto, & Shacklock,

2011). R&D managers frequently query whether R&D professionals can

be “led” (Scott & Bruce, 1998) and face a dilemma of the autonomy need

of professionals and the managerial control (Raelin, 1985).

R&D managers may influence how employees handle their work- or

family-related affairs. At work supervisors can determine professionals'

job autonomy and supply job resources so that they are able to contribute subordinates' innovativeness (Lapierre, Hackett, & Taggar, 2006;

Lee, 2008). Literature also confirms a positive effect of the good

supervisor–subordinate relationship, such as leader–member exchange,

on innovativeness for R&D employees (e.g., Atwater & Carmeli, 2009;

Lee, 2008; Scott & Bruce, 1998). Additionally, a supportive supervisor

is a necessary resource helping mitigate the work–family conflict

⁎ Corresponding author.

⁎⁎ Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses: manllian@ms76.hinet.net (M.-L. Chang), cheng-cf@asia.edu.tw

(C.-F. Cheng).

(Frye & Breaugh, 2004). Consequently, the supervisor plays an important role in managing R&D professionals (Lee, 2008).

Taken together, four entities, including R&D subordinate, immediate

supervisor, job autonomy, and family, are influential in a R&D

subordinate's work and family lives. The perceptions and evaluations

of the R&D subordinate and supervisor about other entities constitute

the connections between entities. The connections among these entities

respectively stand for concepts of leader–member exchange (LMX),

self-determination (i.e., perceptions about job autonomy), managerial

control (related to autonomy support), work–family conflict, and managerial work–family support.

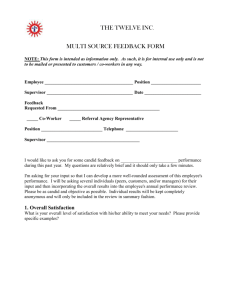

Fig. 1 models the entities and represents the conceptual framework

in a R&D employee's cognition. Specifically, the R&D employee concentrates on these entities and connections when he/she evaluates the

work and family domains. The arrow in Fig. 1 represents one's perception toward the other. Three theories including the conservative resource

theory (COR), social exchange theory (SET), and job demands–control

(JD-C) model help understand why these concepts are particularly

important for R&D employees and how they are closely relevant to

each other.

The essence of COR theory is that individuals seek to obtain and

maintain resources such as time, cognition, and energy (Hobfoll, 1989).

Owing to a fixed amount of resources an individual's investment

of resources in a domain reduces the level of resources available for

investment in another one (Amah, 2009). According to COR theory,

as resources are depleted without adequate replenishment, negative

0148-2963/$ – see front matter © 2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.10.010

Please cite this article as: Chang, M.-L., & Cheng, C.-F., How balance theory explains high-tech professionals' solutions of enhancing job

satisfaction, Journal of Business Research (2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.10.010

2

M.-L. Chang, C.-F. Cheng / Journal of Business Research xxx (2013) xxx–xxx

Subordinate’s

family (X2)

Managerial

work-family

support

Supervisor

(O)

Low

managerial

control

Low

work-family

conflict

Subordinate

(P)

Selfdetermination

Job autonomy

(X1)

Fig. 1. The conceptual framework.

outcomes including the work–family conflict or decreased job satisfaction are likely to result (Harris, Wheeler, & Kacmar, 2011). The work–

family conflict not only represents the result of depleted resources

but also may further exhaust remaining resources. COR theory also

posits that employees in a high quality LMX with their supervisors

are usually provided resources which help replenish their resources

(Harris et al., 2011) so that they may experience less work–family

conflict (Karatepe & Uludag, 2008). Accordingly, COR theory provides

a mechanism through which LMX and the work–family conflict are

related, and explains why they are critical factors for exploring a R&D

employee whose works suck up scores of resources.

SET suggests that the favorable treatment from an exchange partner

creates an obligation to reciprocate (McNall, Nicklin, & Masuda, 2010).

Building on SET, previous studies documented that LMX, job autonomy,

and managerial work–family support improved an employee's organizational commitment and innovation due to the norm of reciprocity

(Agarwal, Datta, Blake-Beard, & Bhargava, 2012; McNall et al., 2010;

Park & Searcy, 2012; Wang, Lawler, & Shi, 2011). Thus, R&D supervisors

can utilize LMX, job autonomy, and managerial work–family support as

resources in exchange for R&D employees' contributions to innovation.

JD-C model posits that the job autonomy acts as a buffer for negative

effects of demanding jobs (Van der Doef & Maes, 1999). Job autonomy,

the important job characteristic for professionals, describes the extent

to which the job provides freedom and discretion to the employee in

scheduling the work and in determining how to conduct it (Park &

Searcy, 2012). While the self-determination defines the employee's

perception of the job autonomy, the managerial control reflects the

supervisor's permission to provide autonomy for subordinates. The

agreement between the self-determination and managerial control

determines whether R&D employees obtain enough job autonomy for

themselves.

JD-C model's extension, job demands–resources (JD-R) model,

regards the job autonomy and managerial work–family support as job

resources which are strongly linked to motivational-based outcomes

(e.g., job satisfaction) (Agarwal et al., 2012; Mauno, Kinnunen, &

Ruokolainen, 2006). Both JD-C and JD-R models imply that R&D supervisors can utilize the job autonomy, LMX, and managerial work–family

support as resources to handle demanding R&D works and thus exchange for R&D employees' contributions to innovation.

COR, SET, and JD-C theories underpin our conceptual framework

which displays complex relationships among four entities in work and

family domains (see Fig. 1). The findings of meta-analyses report that

these factors are linked to important organizational outcomes, particularly the job satisfaction (e.g., Fried, 1991 for autonomy; Gerstner &

Day, 1997 for LMX; Kossek & Ozeki, 1998 for work–family conflict).

Prior studies focus on the separate effects of one or two of these factors

for R&D professionals or other employees, and indicate that employees

have high job satisfactions when they have good LMX, they are satisfied

with the job autonomy, or they have less work–family conflict

(e.g., Farr-Wharton et al., 2011; Mauno et al., 2006; Raelin, 1985).

Although prior studies indicate the individual impact of LMX, autonomy, work–family conflict, and managerial work–family support on the

job satisfaction, they cannot totally explain the job satisfaction in real

life. For example, it is unknown how an employee with a good LMX

evaluates the job satisfaction when he/she is dissatisfied with the job

autonomy. Or how does an employee feel about the job satisfaction

if he/she is satisfied with the job autonomy but experiences a high

work–family conflict? Can the LMX or managerial work–family support

help improve the employee's job satisfaction? Taking all these factors

into account in the research is a critical issue in that they coexist in

the individual cognitive framework and they are interrelated. In other

words, these four entities and their interrelationships dominate the

R&D employee's cognitive structure when he/she evaluates the job

satisfaction.

For answering the above questions, this study applies the balance

theory to exploring how to balance these relationships among R&D

employee, supervisor, job autonomy, and family for creating the higher

job satisfaction. Heider's (1958) balance theory is a meaningful lens for

understanding the interactive effects among these factors. The balance

model is a cognitive framework that describes how an individual perceives others around him/her, and focuses on the cognitive consistency

(Awa & Nwuche, 2010). The “balance” situation or cognitive consistency

means that an individual's perceptions about others achieve the equilibrium instead of contradiction. The basic model in the balance theory is a

triad of a person, other person, and an entity. Relationships between any

two entities determine the balance. For example, if a subordinate and

his/her supervisor have similar opinions about the job (i.e., agreement),

they are likely to establish a good working relationship. This is a socalled balanced situation. If the subordinate does not like the supervisor,

he/she will alter the opinion for achieving the balance among the cognitions, and eventually have the different view from the subordinate.

Individuals strive for the cognitive balance in their cognitions of interpersonal relations (Davidson & Sussmann, 1977). Pleasantness arises

when the cognitive balance is achieved (Carroll, 1977). Accordingly,

the balance theory helps integrate the relevant factors in the individual

cognitive framework and aids understanding how a R&D employee–

supervisor relationship, their perceptions about the job autonomy

and the employee's family can influence the employee's pleasantness

of job (i.e., job satisfaction). Based on the balance theory, this study

attempts to investigate how the balanced or imbalanced cognitive

framework (see Fig. 1) creates the job satisfaction.

Note that the job satisfaction is not included in the framework in

Fig. 1, because job satisfaction is the result of the cognitive framework.

Based on the balance theory, individuals produce pleasantness when

their cognitive structures achieve the balance. The job satisfaction can

be regarded as the pleasantness in terms of the job. The objective of

this study is to identify the appropriate cognitive structure that can

lead to the high job satisfaction.

2. Balance theory

Heider's (1958) balance theory describes the process mechanisms in

the minds of social actors such that a focal person (P) has positive or

negative cognitions about other individual (O) and issue (X). Two actors

and an entity are treated as a three-point cognitive structure equipped

with three relationships. Relationships between entities (e.g., PO, PX,

or OX) denote an individual's cognitions or sentiments about other entities. The cognition or sentiment means the positive (+) or negative

(−) feelings that the individual gives to the other entities (Woodside

& Chebat, 2001). A positive sign (+) denotes that an individual gives

more of a negative item than he/she receives, or that he/she receives

more of a positive item than he/she gives. On the contrary, a negative

sign (−) denotes that an individual receives more of a negative item

than he/she gives, or that he/she gives more of a positive item than

Please cite this article as: Chang, M.-L., & Cheng, C.-F., How balance theory explains high-tech professionals' solutions of enhancing job

satisfaction, Journal of Business Research (2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.10.010

M.-L. Chang, C.-F. Cheng / Journal of Business Research xxx (2013) xxx–xxx

he/she receives (Alessio, 1990). For example, P has a liking for O in that

P receives more positive sentiments from O. Thus, a positive sign tags

the liking between P and O (L+). Otherwise, a negative sign (L−) symbolizes P's dislike for O. Likewise, P may receive fulfillment with respect

to X. Receiving fulfillment is viewable as a reward and thus carries a

positive sign (Alessio, 1990).

In addition to the sentiment, an agreement shape relationships

in the triad (Carson, Carson, Knouse, & Roe, 1997). The agreement

means that P and O share a similar perception about X. Specifically,

the agreement is achieved when P and O have the same positive sentiment toward X (i.e., PX is + and OX is +) or when P and O have the

same negative sentiment toward X (i.e., PX is − and OX is −). The

balance theory often uses the sign A+ to represent the agreement and

uses A− to represent the disagreement.

Individuals seek a balance in the cognitive structure. The balance is

defined as affective states (pleasantness or harmony) and as cognitive

states (expectancy or consistency) (Carson et al., 1997). If an

individual's cognitive structure is imbalanced, he/she will change his/

her attitudes or cognitions for achieving the balance or pleasantness.

In other words, the imbalanced state is the motivational force for modifying or changing the cognitive structure (Awa & Nwuche, 2010).

Whether a triad is balanced is determined by multiplying the signs in

a triad (Cartwright & Harary, 1956). A positive multiplication sign indicates the balance. Specifically, when all three relationships are positive

or when two of the relationships are negative and one is positive, the

balance exists. In other words, the conditions of balance are either

when P and O like each other (L+) and agree in their feelings about X

(A+) or when P and O dislike each other (L−) and disagree in their

feelings about X (A−) (Davidson & Sussmann, 1977).

3. Conceptual framework based on the balance theory

Fig. 1 displays a R&D employee's cognitive structure. In the R&D

employee's mind, there are four entities dominating in the work and

family domains, that is, the R&D employee, his/her supervisor, the job

autonomy, and his/her family. The perceptions of the R&D employee

and the supervisor about other entities determine whether the R&D

employee's cognitive structure is balanced or not. The pleasantness

from the balanced state is a motivational force leading to the efforts to

alter the imbalanced cognitive structure.

This study applies the balance theory to explore the balanced interrelationships of the conceptual framework in Fig. 1. The job satisfaction

is regarded as the proxy of the pleasantness of the balanced state in that

the job satisfaction is one of the motivational-based outcomes (Mauno

et al., 2006). The R&D employee (P), supervisor (O), job autonomy

(X1), and family (X2) represent the entities in the system. The perceptions of P and O about other entities are captured by LMX (PO), selfdetermination (PX1), managerial control (OX1), work–family conflict

(PX2), and managerial work–family support (OX2). Note that the system

does not contain the relationship between the job autonomy and family

(X1X2) because employees' families cannot affect the job. Hence,

the whole structure can be divided into two triads of relationships

(i.e., work and family domains).

3

supervisor–subordinate relationship (PO is denoted as L+) develops

when employees experience a high quality LMX (Graen & Uhl-Bien,

1995). However, the out-group members who have a relatively

low-quality LMX may feel that their hard working exchanges for unfair

treatment (Gerstner & Day, 1997). Thus, the PO is labeled as a negative

sign (L−).

3.2. Self-determination (PX1)

In terms of the employee's perception about the job autonomy

(PX1), the self-determination reflects the employee's sense of autonomy

about workplace choices such as making decisions about work methods,

pace, and effort (Spreitzer, 1995). Individuals tend to regard autonomy

as an intrinsic motivation (Gagné & Deci, 2005), and they feel high levels

of self-determination when their needs for autonomy are fulfilled (Van

den Broeck, Vansteenkiste, De Witte, Soenens, & Lens, 2010). According

to the balance theory, P will view the receiving as a reward and thus

carry a positive sign if P receives the fulfillment with respect to X

(Alessio, 1990). Thus, the PX1 is positive when the subordinate feels

self-determination.

3.3. Managerial control (OX1)

Self-determination theory also proposes that the supervisor's autonomy support is one of the critical contextual factors that affect need

satisfaction (Baard, Deci, & Ryan, 2004). The autonomy support

denotes the supervisor's perception about the job autonomy. However,

this study adopts the term “managerial control” instead of autonomy

support, because control is a fundamental management activity

(Theodosiou & Katsikea, 2007). Managerial control is regarded as an

opposite of autonomy support (Gagné, 2003). Baard et al. (2004)

view them as two ends in a continuum. The higher autonomy support

(i.e., less managerial control) involves the supervisor listening and acknowledging the subordinate's viewpoints and feelings, giving a meaningful rationale for a request, and encouraging self-initiation (Moreau &

Mageau, 2012). The highly managerial control involves the supervisor

prescribing a solution and demanding, communicating performance

standards, and monitoring and evaluating behaviors and outcomes

(Baard et al., 2004).

Although managerial control is the embodiment of power, delegation is more attractive owning to the supervisor's limits of time and

energy (Bauer & Green, 1996). In other words, when the supervisor

releases his/her managerial control, he/she can save some efforts and

costs on monitoring or directing the subordinate's works and receive

the subordinate's assistance. In terms of the employee's stand, the low

managerial control means that the employee receives more autonomy.

As a result, the presence of the low managerial control is labeled as

a positive sign in that low managerial control can be regarded as a

saving of effort for a supervisor and a receiving of autonomy for a

subordinate.

3.1. LMX (PO)

3.4. Work–family conflict (PX2)

LMX is definable as perceptions of the quality of the interpersonal

exchange relationship between a supervisor and his/her subordinate,

indicating the extent to which the supervisor and subordinate exchange

resources and support beyond the formal employment contract

(Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). According to the balance theory, whether

the supervisor–subordinate relationship (PO) carries a positive or negative sign depends on a gestalt of attraction, desire, giving, and receiving

(Alessio, 1990). The in-group members who establish a high-quality

LMX receive various resources and benefits and thus return their loyalty

and extra supports to the supervisor (Basu & Green, 1997). A positive

Netemeyer, Boles, and McMurrian (1996) define work–family

conflict as a form of inter-role conflict in which the role pressures

from the work and family domains are mutually incompatible, such

that participation in one domain is made difficult through participation

in another. The work–family conflict involves various negative feelings

such as tensions, struggles, depression, psychological distress, and burnout (Qu & Zhao, 2012) so that the work–family conflict is a negative

item. Accordingly, individuals experiencing low levels of work–family

conflict label PX2 a positive sign in that either they receive seldom

negative item or they can fulfill family-related affairs.

Please cite this article as: Chang, M.-L., & Cheng, C.-F., How balance theory explains high-tech professionals' solutions of enhancing job

satisfaction, Journal of Business Research (2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.10.010

4

M.-L. Chang, C.-F. Cheng / Journal of Business Research xxx (2013) xxx–xxx

3.5. Managerial work–family support (OX2)

Work–family culture refers to the extent to which work environment is supportive of the integration of employees' work–family

needs (Mauno et al., 2006). The managerial work–family support is

the most important aspect of work–family culture because supervisors

influence the way employees experience and perceive the organizational culture (Thompson, Beauvais, & Lyness, 1999). Supervisors who have

high managerial work–family support are sensitive to employees'

family responsibilities and empathize with employees' desire to seek

the balance between work and family spheres (Frye & Breaugh, 2004).

Thus, employees receive more support and label OX2 as a positive sign.

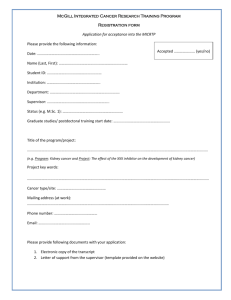

The positive/negative relationships among these entities in the system constitute 32 combinations in total (see Fig. 2). Fig. 2a describes

the balanced work and family domains involving a high LMX (L+)

and an agreement on the supervisor's and subordinate's perceptions

of the job autonomy and family (A+), or a low LMX (L−) and an disagreement on the supervisor's and subordinate's perceptions of the job

autonomy and family (A−). While Fig. 2b shows the balanced work domain (L+A+ or L−A−) and imbalanced family domain (L+A− or L−

A+), Fig. 2c shows the imbalanced work domain (L+A− or L−A+)

and balanced family domain (L+A+ or L−A−). Fig. 2d focused on the

completely imbalanced work and family domains in which the subordinate likes his/her supervisor but disagree with the supervisor (L+A−),

or the subordinate dislikes his/her supervisor but agree with the supervisor (L−A+). The objective of this study is to find out the best system that

can lead to a higher job satisfaction from these combinations. In this

regard, the idea of the balance theory helps identify the balanced ones,

Fig. 2. a. Complete balance (Balance in work and family). Note: L+ denotes high LMX and L− denotes low LMX. A+ denotes an agreement between PO and A− denotes a disagreement

between PO. b. Incomplete balance (Balance in work and imbalance in family). Note: L+ denotes high LMX and L− denotes low LMX. A+ denotes an agreement between PO and

A− denotes a disagreement between PO. c. Incomplete balance (Imbalance in work and balance in family). Note: L+ denotes high LMX; L− denotes low LMX. A+ denotes an

agreement between PO and A− denotes a disagreement between PO. d. Complete imbalance (Imbalance in work and family). Note: L+ denotes high LMX; L− denotes low LMX.

A+ denotes an agreement between PO and A− denotes a disagreement between PO.

Please cite this article as: Chang, M.-L., & Cheng, C.-F., How balance theory explains high-tech professionals' solutions of enhancing job

satisfaction, Journal of Business Research (2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.10.010

M.-L. Chang, C.-F. Cheng / Journal of Business Research xxx (2013) xxx–xxx

5

Fig. 2 (continued).

that are rated as a high pleasantness (i.e., job satisfaction), from 32

combinations.

4. Hypothesis development based on balance theory

The balance is an interaction between the like (L) and agreement

(A) (Zajonc, 1968). Heider (1958) proposes that balanced structures

(L+A+ and L−A−) can lead to a pleasant state and imbalanced structures (L−A+ and L+A−) may produce tension. Newcomb (1968) and

Price, Harburg, and Newcomb (1966) further suggest that when P likes

O (L+), a structure involving agreement (A+) was balanced and should

be highly preferred, and a structure involving disagreement (A−) was

unbalanced and should be least preferred. Other relevant studies on

balance theory admit that the L+A+ situations were highly preferred,

but they find that the L+A− situations frequently receive a rating similar to other situations (L−A+ and L−A−) (Davidson & Sussmann,

1977; Sussmann & Davis, 1975; White, 1977).

These relevant studies view the L+A+ structure involving the likeness, agreement, and balance is a highly attractive situation. Of L+A+

situations, other studies particularly distinguish the agreement in a positive sentiment (+++) from the agreement in a negative sentiment

(+−−), and find that the balanced situation involving two negative

Table 1

Characteristics of the respondents.

Characteristics

Gender

Age

Education

Female

Male

b40 years old

N40 years old

Vocational school

College

Master

Ph.D.

Others

Subordinates

Supervisors

98 (21.2%)

365 (78.8%)

288 (62.2%)

175 (37.8%)

68 (14.7%)

190 (41.0%)

173 (37.4%)

10 (2.2%)

22 (4.8%)

1 (0.9%)

105 (99.1%)

12 (11.3%)

94 (88.7%)

0 (0.0%)

9 (8.5%)

81 (76.4%)

16 (15.1%)

0 (0.0%)

Please cite this article as: Chang, M.-L., & Cheng, C.-F., How balance theory explains high-tech professionals' solutions of enhancing job

satisfaction, Journal of Business Research (2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.10.010

6

M.-L. Chang, C.-F. Cheng / Journal of Business Research xxx (2013) xxx–xxx

Table 2

Measurements.

Factor

Reference

LMX (PO)

Graen and Uhl-Bien

(1995)

Sample item

Respondent

1. I usually know how satisfied my immediate supervisor is with what I do.

2. My immediate supervisor understands my problems and needs.

3. My immediate supervisor recognizes my potential.

4. Regardless of how much formal authority my immediate supervisor has built into

his or her position, my supervisor would be personally inclined to use his or her

power to help me solve problems in my work.

5. Regardless of amount of formal authority my immediate supervisor has, I can count

on my supervisor to “bail me out” at his or her own expense when I really need it.

6. I have enough confidence in my immediate supervisor that I would defend and

justify his/her decisions if he/she were not present to do so.

7. My working relationship with my immediate supervisor is extremely effective.

Self-determination (PX1)

Spreitzer (1995)

1. I have significant autonomy in determining how I do my job.

2. I can decide on my own how to go about doing my work.

3. I have considerable opportunity for independence and freedom in how I do my job.

Managerial control (OX1)

Kohli, Shervani, and

1. I inform my subordinates about the activities they are expected to perform.

Challagalla (1998)

2. I monitor how my subordinates perform required activities.

3. I evaluate the skills my subordinates use to accomplish a task.

4. I assist my subordinates by suggesting why using a particular approach

may be effective.

5. I tell my subordinates about the expected level of achievement on targets.

6. I monitor my subordinates' progresses on achieving targets.

7. I ensure that my subordinates are aware of the extent to which they attain targets.

Work–family conflict (PX2) Netemeyer et al. (1996) 1. The demands of my work interfere with my home and family life.

2. The amount of time my job takes up makes it difficult to fulfill my family responsibilities.

3. Things I want to do at home do not get done because of the demands my j

ob puts on me.

4. My job produces strain that makes it difficult to fulfill my family duties.

5. Due to work-related duties, I have to make changes to my plans for family activities.

Managerial work–family

Thompson et al. (1999) 1. In general, I am quite accommodating of my subordinate's family-related needs.

support (OX2)

2. I am sympathetic toward my subordinate's family-related responsibilities.

3. In the event of a conflict, I understand when my subordinate has to put his/her family first.

4. I encourage my subordinate to strike a balance between work and family lives.

5. In this organization it is generally okay to talk about one's family at work.

Job satisfaction

Price (1997)

1. I am able to keep busy all the time.

2. I have the chance to work alone on the job.

3. I have the chance to do different things from time to time.

4. I have the chance to be “somebody” in the community.

5. I am satisfied with the way my boss handles his/her workers.

6. I am satisfied with the competence of my supervisor in making decisions.

7. I am able to do things that don't go against my conscience.

8. My job provides for steady employment.

9. I have the chance to do things for other people.

10. I have the chance to tell people what to do.

11. I have the chance to do something that makes use of my abilities.

12. I am satisfied with the way company policies are put into practice.

13. I am satisfied with my pay and the amount of work I do.

14. I have the chances for advancement on this job.

15. I have the freedom to use my own judgment.

16. I have the chance to try my own methods of doing the job.

17. I am satisfied with the working conditions.

18. I am satisfied with the way my supervisor gets along with me.

19. I receive the praise I get for doing a good job.

20. I have the feeling of accomplishment I get from the job.

sentiments was deemed unpleasant (Basil & Herr, 2006; Carson et al.,

1997).

Accordingly, the balanced structures determined by L+A+ in work,

family, or both domains should lead to the higher job satisfaction than

others. Specifically, when P likes O, and they have consistently positive

sentiments about X1 or X2, P may produce a higher job satisfaction. The

argument that the combination of three positive sentiments (+++) is

evaluated as a higher job satisfaction is well-founded, because relevant

studies in the organizational behavior field document that the LMX, autonomy, low work–family conflict, and high managerial work–family

support have respectively positive effects on the subordinate's job

satisfaction (Fried, 1991; Gerstner & Day, 1997; Kossek & Ozeki, 1998;

Mauno et al., 2006).

States a2, b1, b2 in Fig. 2a and b, which involve three positive relations and balance in the work domain (+++ in the work domain),

and state a3, c1, c3, which involve three positive relations and balance

in the family domain (+++ in the family domain), and state a1,

Cronbach alpha

Subordinate 0.67

Subordinate 0.76

Supervisor

0.74

Subordinate 0.66

Supervisor

0.77

Subordinate 0.98

which has three positive relations and balance in both work and family

domains (+++ in the work and family domains) are preferable in

terms of their likely association with the high job satisfaction. State a1

which simultaneously achieves balances in two domains should lead

to the highest job satisfaction. Although state a2, b1, b2, a3, c1, and c3

relate to L+A+ and balance in only one domain, the subordinate's

Table 3

Means, standard deviations, correlations.

Variables

Mean S.D.

1. LMX (PO)

2. Self-determination (PX1)

3. Low managerial control (OX1)

4. Low work–family conflict (PX2)

5. Managerial work–family support

(OX2)

6. Job satisfaction

4.30

4.47

4.15

4.45

4.41

0.52

0.63 −.17

0.64

.60

.20

0.65 −.57 −.06 −.38

0.78

.45 −.01

.47 −.02

1.

2.

4.65

1.29

.18

3.

.61

4.

5.

.37 −.02 .35

Please cite this article as: Chang, M.-L., & Cheng, C.-F., How balance theory explains high-tech professionals' solutions of enhancing job

satisfaction, Journal of Business Research (2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.10.010

M.-L. Chang, C.-F. Cheng / Journal of Business Research xxx (2013) xxx–xxx

positive relationship with the supervisor (L+) allows for positive spillover effect between work and family domains (Culbertson, Huffman, &

Alden-Anderson, 2010).

In terms of states a2, b1, and b2 (+++ in the work domain), an ingroup subordinate receives the autonomy from the supervisor due to a

high trust and high support (Basu & Green, 1997). LMX results in the

subordinate's self-determination (Agarwal et al., 2012), in that the

subordinates are capable of and allowed for participating in decision

making and solving problems (Farr-Wharton et al., 2011). A subordinate in a high quality LMX has broad negotiating latitude to reduce

the excessive workload or difficulty of tasks, and thus is capable of managing the imbalance between work and family domains and alleviating

conflicts (Major, Fletcher, Davis, & Germano, 2008). Thus, the balance in

the work domain can protect the subordinate's job satisfaction from the

imbalance in the family domain.

For states a3, c1, and c3 (+++ in the family domain), subordinates

can benefit from either the balance in the family domain or the high

quality LMX. The subordinates report less work–family conflicts when

their supervisors are more supportive of balancing work and family demands (Frye & Breaugh, 2004). Harris, Wheeler, and Kacmar (2009)

suggest that LMX should be most important for the subordinates who

perceive minimal self-determination from their jobs. By virtue of

supports from work and family domains, the subordinates feel relieved

in performing assigned tasks.

H1. Causal recipes a1, a2, a3, b1, b2, c1, c3 (L+A+ in one domain) are

possible causal combinations of the high job satisfaction.

Based on the balance theory, state a1 (+++ in the work and family

domains) is the theoretically most favorable case among all the possible

combinations. But the worst case is debatable. This study proposes

that the worst cases are state c8 (L−A+ in work domain with low job

autonomy and L−A− in family domain with work–family conflict)

and d8 (L−A+ in both domains with negative sentiments toward job

autonomy and family). The rationale lies in that the vicious cycle of

the LMX and work–family conflict devours any benefits that the subordinates should gain from their supervisors. On one hand, the

subordinate's heavy family role results in his/her weaker contributions

at work and thus deters him/her from developing a high quality LMX

with his/her supervisor (Lapierre et al., 2006). On the other hand, the

subordinate in a low quality LMX perceives his/her job demands as hindering his/her ability to achieve goals and thus feels frustration, which

spills over outside of work to cause the high work–family conflict

(Culbertson et al., 2010). In addition, a supervisor utilizes supervision

techniques with subordinates in the low quality LMX (Aryee & Chen,

2006), and thus the supervisor may put increasing managerial control

on them.

H2. The best combination is state a1 (L+A+ in both domains) that leads

to the highest subordinate's job satisfaction among all combinations.

H3. The worst combinations are state c8 and d8 (low LMX and job

autonomy, but high work–family conflict) that lead to the lowest

subordinate's job satisfaction among all combinations.

5. Method

5.1. Technique of analysis

This study employs the qualitative comparative analysis using fuzzy

sets (fsQCA) tools (Ragin, 2008a) for investigating H1 and MANOVA for

examining H2 and H3. Almost all social science theory is formulated in

terms of set relations. The fsQCA is an appropriate tool for identifying

the causal conditions of occurrence in the real world (Berg-Schlosser,

De Meur, Rihous, & Ragin, 2009). The causal condition refers to a sufficient condition to produce a given outcome of interest (Ragin, 2008b).

7

Table 4

Causal combinations of job satisfaction.

Causal conditions

Paths leading to the job satisfaction a

1

LMX

Self-determination

Low managerial control

Low work–family conflict

Managerial work–family support

Raw coverage

Unique coverage

Consistency

Counterpart c

2

b

●

●

○

●

0.53

0.00

0.91

b2,d2

●

●

●

○

0.55

0.03

0.93

a2,b2

3

●

●

●

●

0.65

0.02

0.90

a1,d5

4

●

●

●

●

0.64

0.02

0.91

a1,c3

a

Frequency threshold = 1; consistency threshold = 0.90; solution coverage = 0.72;

solution consistency =0.88.

b

Black circles “●” indicate the presence of causal conditions (i.e., antecedents). White

circles “○” indicate the absence or negation of causal conditions. The blank cells represent

“don't care” conditions, meaning that the causal path always leads to the outcome variable

without regard to the levels of the “don't care” conditions.

c

Counterpart column displays the state numbers in Fig. 2 that are the counterparts of

the specific causal combinations.

In other words, the presence of the condition always leads to the outcome, but the condition is not the only cause. The fsQCA applies Boolean

algebra and results in a logical statement describing for different combinations of causal conditions leading to the same outcome (BergSchlosser, De Meur, Rihous, & Ragin, 2009). This study attempts to identify the combinations of LMX, self-determination, managerial control,

work–family conflict, and managerial work–family support in the R&D

employee's cognitive structure resulting in the R&D employee's job satisfaction. The feature of fsQCA can help identify these causal combinations.

Collecting sufficient cases for every possible combination in Fig. 2

would be extremely difficult. Even if we strive to expand the total sample size, it is still possible that some combinations have plenty cases and

others have a deficiency. In this regard, examining the effects of combinations without cases on the outcome variable by conventional multivariate techniques is unthinkable. However, fsQCA produces solutions

by taking account of “remainders” that are the combinations without

cases in Ragin's language (Ragin, 2009). Moreover, fsQCA assists in

assigning total cases to those combinations in Fig. 2 according to the

levels of research variables. This procedure aids subsequent analyzing

by MANOVA. Based on the foregoing reasons, fsQCA is an appropriate

technique for examining the hypothesis.

5.2. Sample

This study narrows the research scope to the R&D employees in

high-tech enterprises in Taiwan. The high-tech sectors in Taiwan

cover the electronics, semiconductor, biotechnology, and pharmaceutical industries (Chih & Lin, 2009). By using a convenience-sampling

method, we found the sample companies which had R&D functions

and belonged to the high-tech industries. Through mail and phone

calls, we first asked R&D managers in sample companies to consent to

participate in our study. After obtaining R&D managers' approval of

our invitation, we sent confirmation letters to the R&D managers and

asked for their lists of members under their supervisions. The lists

included R&D subordinates' names and office phone numbers.

Based on the lists, three to five subordinates for a supervisor in

each sample firm were randomly designated to participate in the survey

by this study. We then contacted with these R&D subordinates for

obtaining personal approval of participating, their marital status, and

mail addresses. Note that we included only individuals who have a

family (i.e., they were married or had children) because we focused

on work–family interactions. Then we sent a survey instrument,

including a cover letter addressed personally, a questionnaire, and a

postage-paid return envelope to each participant. In a cover letter, we

guaranteed confidentiality. Supervisors received a questionnaire listing

Please cite this article as: Chang, M.-L., & Cheng, C.-F., How balance theory explains high-tech professionals' solutions of enhancing job

satisfaction, Journal of Business Research (2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.10.010

8

M.-L. Chang, C.-F. Cheng / Journal of Business Research xxx (2013) xxx–xxx

Table 5

The comparison of job satisfaction across states.

State a

a1

Sample size

Job satisfaction

F (p-value)

Post hoc comparisonb

a

b

a2

a3

a8

76

58

42

66

5.97

5.48

5.17

5.25

187.67 (0.000)

(c8, d8, b7 d2, c7, c3, b2 a3 a8, a8 a2, a1)

b2

b7

c3

c7

c8

d2

d8

57

5.16

33

3.09

27

4.10

24

3.67

23

2.34

22

3.31

35

2.76

The respondents were assigned to each state according to the levels of causal conditions. The job satisfaction scores for states that had respondents are compared.

States are listed in ascending order according to the job satisfaction scores. And states that are significantly different are separated by a comma.

their subordinates' names that participated in the survey and were

asked to rate their managerial controls and managerial work–family

supports for each of these subordinates. Subordinates were asked to respond the items with respect to LMX, self-determination, work–family

conflict, and job satisfaction.

For assuring confidentiality, each participant completed his/her own

questionnaire and had no clue about colleagues' questionnaires.

We marked each questionnaire with a simple letter of the alphabet

before sending out to participants in order to pair the supervisor's and

subordinate's questionnaires. We mailed a total of 990 supervisor–

subordinate pairs of questionnaires to 198 firms. Finally, we obtained

463 supervisor–subordinate pairs of questionnaires from 106 companies, producing a response rate of 47%. These 463 subordinates are

supervised by 106 subordinates. Table 1 shows the sample profile.

5.3. Measurement

In the present research, all variables were analyzed at individual

level of analysis. The measures that were consistent with our definitions

of concepts, were well-designed and widely applied, and have fewer

items were better. A pilot study was conducted for confirming the fitness of translation and selecting items. Except the managerial control,

the measures of constructs were consistent with the literature. The

number of items for the managerial control was excess. Only seven

items that have higher factor loadings and item-to-total correlations

were retained. Based on the pilot study, we developed the formal questionnaire and conducted the survey. Table 2 summarizes all items and

detailed information for the research constructs. LMX were measured

using seven items each that drew from Graen and Uhl-Bien (1995). An

example for LMX includes “I usually know how satisfied my immediate

supervisor is with what I do.” The Coefficient alpha for LMX was .67.

While three items measured the self-determination based on

Spreitzer (1995) (e.g., I have significant autonomy in determining

how I do my job), seven items measured the managerial control based

on Kohli et al. (1998) (e.g., I inform my subordinates about the activities

they are expected to perform). Coefficient alphas were .76 for the selfdetermination and .74 for the managerial control. Five items measured

the work–family conflict based on Netemeyer et al. (1996) (e.g., “The

demands of my work interfere with my home and family life”) and

five items measured the managerial work–family support based on

Thompson et al. (1999) (e.g., “In general, I am quite accommodating

of my subordinate's family-related needs”). Coefficient alphas were

.66 for the work–family conflict and .77 for the managerial work–family

support. The measures of the job satisfaction drew from Price (1997)

including 20 items (e.g., I am able to keep busy all the time). The coefficient alpha was .98.

Items related to LMX, self-determination, work–family conflict, and

job satisfaction were responded by R&D employees. Although LMX is

generally considered a dyadic construct, we focused on the subordinates' perceptions of LMX in that we were interested in the subordinates' outcomes. In order to avoid the presence of potential common

method variance, supervisors were asked to respond the managerial

control and managerial work–family support for each designated

subordinate. Managerial control in salesperson-relevant literature was

usually rated based on individual level (e.g., Baard et al., 2004).

Likewise, the managerial work–family support may be differently and

personally available to individuals and can be conceptualized and measured at the individual level (Wang et al., 2011). Accordingly, the supervisors had to respond these items personally.

Participants indicated the degree to which each statement applies to

them using a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strong disagree)

to 7 (strongly agree). The Cronbach's alphas for these factors were

above 0.60 so that the internal consistency was acceptable (Hair,

Black, Babin, & Anderson, 2010). We then computed the average score

of items for each factor for subsequent analysis. Note that the presence

of a factor means the presence of a positive item according to the balance theory. Thus, the managerial control and work–family conflict

were reversed by subtracting scores from 7, in that OX1 and PX2 were

labeled a positive sign when these factors are low. Table 3 provides

means, standard deviations, and correlations.

6. Analyses

6.1. Calibration

To empirically accomplish this identification of causal processes,

QCA proceeds in three steps. The first step is to transform all research

constructs into fuzzy sets. In order to transform Likert scores into

fuzzy membership scores, variables are calibrated for their degree of

membership in sets of cases to produce scores ranging from 0.00 to

1.00 (Ragin, 2008b). Interval scale variables are converted to fuzzy set

membership scores by using the calibrating function of fsQCA software

(Ragin, 2008b) following the procedure detailed in Ragin (2008a).

In order to calibrate variables, the analyst needs to specify the values

of an interval-scale variable that correspond to three qualitative anchors

that structure a fuzzy set (Ragin, 2009) including the threshold for full

membership (fuzzy score = 0.95), the threshold for full nonmembership (fuzzy score = 0.05), and the cross-over point (fuzzy

score = 0.5), where there is maximum ambiguity regarding whether a

case is more “in” or more “out” of a set (Ragin, 2008b). In specifying

these qualitative anchors, the researcher develops a rationale for each

breakpoint (Ragin, 2009). To match fuzzy set calibration with the

Likert-type seven-point scales used in this study, the researchers set

the original values of 7.0, 1.0, and 4.0 to correspond to the full membership, full non-membership, and cross-over anchors, respectively.

6.2. Constructing the truth table

The second step is to using these fuzzy set scores to construct a data

matrix as a truth table with 2k rows, where k is the number of causal factors, to operate the Boolean algebra (Ragin, 2008b). The number of rows

in the truth table equals to the number of logically possible combinations of values on the causal conditions (Ragin, 2008b). For example,

two factors produce four (22) possible combinations including the

presence of both factors, the absence of both, the presence of the first

factor and absence of the second factor, and the presence of the second

factor and absence of the first factor In this study, the initial truth table

has 32 rows representing all logically possible combinations of causal

Please cite this article as: Chang, M.-L., & Cheng, C.-F., How balance theory explains high-tech professionals' solutions of enhancing job

satisfaction, Journal of Business Research (2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.10.010

M.-L. Chang, C.-F. Cheng / Journal of Business Research xxx (2013) xxx–xxx

conditions. Each row is the counterpart of a state in Fig. 2. The positive

sign means the presence of the factor, whereas the negative sign

means the absence of the factor.

The third step reduces the initial truth table by specifying the frequency threshold and consistency threshold. The frequency threshold

is to determine which combinations of conditions are relevant by specifying the number of cases with greater than 0.5 membership in each

combination (Ragin, 2009). According to Ragin (2008b), we selected

the frequency threshold as 1 for analysis, capturing 99% of the cases in

the study which is above Ragin's (2008b) criterion. The consistent

threshold is to indicate which combinations exhibit high scores in the

outcome (Ragin, 2008b). Consistency scores measure the degree to

which combinations are subsets of high scores in the outcome. Combinations with consistency scores at or above the threshold are coded 1,

whereas those below the threshold are coded 0 (Ragin, 2009). Ragin

(2008b) suggests that gap in the upper range of consistency was useful

for establishing a consistency threshold and that the threshold below

0.75 indicates substantial inconsistency. Thus, this study set the consistency threshold at 0.90.

9

were assigned to states in Fig. 2 according to fuzzy set scores of all variables. The fuzzy score of a factor above or equal to 0.5 represents the

presence of a factor, whereas the fuzzy score of a factor less than 0.5 represents the absence of the factor (Ragin, 2008b). For example, a highquality LMX is present as its value exceed 0.5, and a low-quality LMX

is present as its value is lower than 0.5. Based on this rule, if all factors

of a case exceed or equal to 0.5, meaning all relations are designated

positive signs, the case is assigned to state a1. Likewise, a case with

fuzzy set scores of LMX, low managerial control, and low work–family

conflict greater than 0.5 and low scores of self-determination and managerial work–family support less than 0.5 is assigned to state d1.

The study includes comparing job-satisfaction scores of states that

have cases. Table 5 indicates that these states have significantly different job satisfaction (F = 187.67, p b .000). State a1 has the significantly

highest job satisfaction and state c8 and d8 have the significantly lowest

job satisfaction. Apart from state c8 and d8, the job satisfactions of states

c7, d2, and b7 are lower than 4 point, indicating R&D works are unsatisfactory. Accordingly, the findings support H2 and H3.

8. Conclusion

7. Results

7.1. Causal conditions of job satisfaction

Based on the Boolean algebra, the fsQCA can produce the causal conditions which are the sufficient conditions for the outcome. Table 4 provides the solutions for causal conditions. For enhancing the readability

and simplicity of the presentation, simple notations in which black

circles indicate the presence of a causal condition and white circles indicate the absence or negation of a condition substitute for the raw logical

statement for each combination introduced by Ragin (2008a). For example, the description by notations for the first path in Table 4 signals

a logical statement “the presence of LMX, the presence of low managerial control, the absence of low work–family conflict, and the presence

of managerial work–family support.”

Table 4 shows that four causal combinations of conditions lead to the

high subordinate's job satisfaction. These causal combinations are the

counterparts of state a1, a2, b2, c3, d2, and d5 (see the last row of

Table 4). For example, the first path, which denotes the situation involving the high LMX, low managerial control, high work–family conflict,

and high work–family support without regard to the level of the selfdetermination, corresponds to the state b2 (L+A+ in work domain

and L+A− in family domain with high work–family conflict) and d2

(L+A− in both domains with low self-determination and high work–

family conflict).

Consistency measures the degree to which configurations are subsets of the outcome (Ragin, 2008b) which is akin to significance metrics

in statistical hypothesis testing (Woodside & Zhang, 2011). High consistency also indicates that a subset relation exists and supports an argument of sufficiency (Ragin, 2009). Table 4 shows that all consistency

values exceed 0.90, indicating these combinations are sufficient conditions causing high job satisfaction.

Raw coverage and solution coverage measure the extent to which the

combinations account for the outcome (Ragin, 2008b), which are akin to

the effects size in statistical hypothesis testing (Woodside & Zhang,

2011). Unique coverage measures the proportion of memberships in

the outcome explained solely by each individual combination (Ragin,

2008b). All of the raw and solution coverage values in Table 4 are above

50%, indicating the combinations explain a large proportion of job satisfaction. Accordingly, states a1, a2, b2, c3, d2, and d5 in Fig. 2 are significant

causal conditions of high job satisfaction, partially supporting H1.

7.2. The Best and Worst States

Among all of 32 possible combinations, this study attempts to identify the best and the worst states. For achieving this purpose, all cases

This study critically analyzes and synthesizes the major theoretical

and empirical body of knowledge of critical factors with a view to proffering a tetragonal-relationship system containing work and family domains for R&D professionals. Based on the balance theory, this study

identified the causal conditions (i.e., combinations of critical factors)

of R&D employees' job satisfactions. Understanding the implications of

causal conditions for the job satisfaction should interest employers of

R&D workers because R&D workers represent expensive competitive

resources to their organizations (Hsieh & Tsai, 2007). The findings

provide valuable implications for managing R&D professionals.

The findings indicate that states a1, a2, b2, and c3 have the particularly higher job satisfaction among the causal conditions. These states

are in common of the positive LMX. This result is consistent with the

LMX-related literature. From meta-analytic research Gerstner and

Day's (1997) conclude that LMX relates positively to the job performance, job satisfaction, commitment, and role clarity, and negatively relates to the role conflict and turnover intentions. Other studies confirm

the positive effect of LMX on the innovativeness for R&D employees

(e.g., Atwater & Carmeli, 2009; Lee, 2008). Additionally, Aryee and

Chen (2006) indicate that LMX was particularly important for Chinese

societies due to the person-oriented nature in relation to Confucianism.

Thus, the conditions with LMX plus the high job autonomy (low

managerial control and high self-determination) result in the balanced

work domain and thus lead to the high job satisfaction. The employee

with a great deal of autonomy feels responsible for works and can conduct works effectively so that he/she can reciprocate the benefits that

they enjoy from the high-quality LMX relationships with their supervisors and translate the privileges associated with the high-quality LMX

into creative work involvement (cf. Farr-Wharton et al., 2011; Park &

Searcy, 2012; Volmer, Spurk, & Niessen, 2012). Thus, LMX provides

beneficial resources for performing tasks whereas the job autonomy

provides capabilities.

Employees in states a2 and b2 achieve a balanced work domain and

experience the high work–family conflict. The finding may explain by

the border theory which concerns the influence of flexibility on role

blurring. Employees who are granted autonomy may experience more

role blurring and thus higher levels of work–family conflict (Glavin &

Schieman, 2012). However, state b1 (i.e., a balanced work domain

with low work–family conflict) is not a causal condition for the high

job satisfaction. This implies that additional benefits of high LMX

would be more significant for those subordinates experiencing high

role conflict (Dunegan, Uhl-Bien, & Duchon, 2002).

Although employees in state c3 face situations associated with the

presence of managerial control or the absence of self-determination,

their relationships with supervisors dominate their job satisfaction.

Please cite this article as: Chang, M.-L., & Cheng, C.-F., How balance theory explains high-tech professionals' solutions of enhancing job

satisfaction, Journal of Business Research (2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.10.010

10

M.-L. Chang, C.-F. Cheng / Journal of Business Research xxx (2013) xxx–xxx

Kacmar, Zivnuska, and White (2007) conclude that in-group employees

in highly centralized situations feel that they have indirect power due to

the increased power their bosses retains in decision making.

Contrary to the balance theory, state d5 which features imbalance in

both work and family domains is one of the causal conditions of the job

satisfaction. Although subordinates cannot enjoy benefits of LMX, they

may have less stress and less intention to turnover than subordinates

in the high-quality LMX (Harris & Kacmar, 2006). The key of state d5

is associated with the job autonomy. If employees are granted empowerment and thus motivated by the job itself, the relationship with a

supervisor is of less importance (Harris et al., 2009). Additionally, this

finding documents the importance of agreement—which is consistent

with Zajonc (1968) report that agreement has the greatest effect on

pleasant ratings.

8.1. Theoretical and practical implications

This study makes several theoretical and practical contributions.

First, several studies apply the balance theory to the consumer behavior

research (e.g., Basil & Herr, 2006; Carson et al., 1997; Woodside &

Chebat, 2001). The study demonstrates how the balance theory is useful

theoretically for linking modes of thinking and organizational behavior.

Second, we describe empirical examinations in organizational behavior

research of balance-theory hypotheses. The fsQCA enables the recognition of causal conditions that are sufficient for the outcome. Third, the

findings indicate that the LMX and agreement on the managerial control

and self-determination are the critical conditions for leading to the job

satisfaction. This is consistent with the COR and SET theories that the

LMX and autonomy are the necessary resources for R&D employees.

Fourth, the findings add an important nuance for the JD-C theory.

The JD-C theory underlines the important role of job autonomy. The

findings support the role of autonomy given the balanced cognitive

structure in the work or family domain. In addition, the findings indicate

that a R&D employee does not perceive the high job satisfaction

when he/she cannot obtain enough autonomy, even if he/she achieves

cognitive balance in the work or family domain. As a result, the selfdetermination and the cognitive balance are necessary for the high job

satisfaction.

Fifth, the findings do not completely conform to the balance theory.

Most causal combinations of conditions are the balanced states in the

work or family domain except for state d5 (L−A+ in both domains

with positive sentiments toward job autonomy and family). However,

the result concludes that the agreement on the high job autonomy

between the supervisor and subordinate is critical when the LMX is

low-quality. Inconsistent with the prior studies relate to the balance

theory (e.g., Davidson & Sussmann, 1977; Heider, 1958; Newcomb,

1968; Price et al., 1966; Sussmann & Davis, 1975; White, 1977), this

study finds that an imbalanced cognitive structure involving agreement

on the high job autonomy can also create the high job satisfaction.

This finding reflects not only the JD-C theory that the job autonomy is

an important job characteristic but also R&D professionals' need for

autonomy.

Sixth, retaining the best professional talent and controlling the costs

associated with human resources practice continue to be a challenge

(Agarwal et al., 2012). Our findings proffer implications to manage

R&D professionals. In addition to the ideal condition (i.e., state a1)

that may be hard to achieve for R&D professionals, this study offers

other options that also create the high job satisfaction. R&D managers

can view the findings as guidelines to balance the managerial control

and autonomy.

8.2. Research limitations and future research directions

The study includes limitations that suggest some directions for future research. First, the study focuses on the subordinate's perspective

for concentrating on the subordinate's cognitive balance. Although

Heider emphasizes that relations between entities are not always

symmetrical (e.g., “P likes O” does not necessarily imply “O likes P”),

he also proposes that such relations tend to become symmetrical

because people tended to like people who like them (Woodside &

Chebat, 2001). However, the concept of reciprocity is a significant

component of balance (Zajonc & Bumstein, 1965). The future research

should include invitations to both supervisors and subordinates to rate

LMX perceptions (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995) whereas work–family

conflict should include work–family conflict and family–work conflict

(Netemeyer et al., 1996).

Second, Hirst et al. (2008) report that the nationality moderates the

relationship between autonomy support and job stress. Thus, the future

research can further compare the employees' cognitive structures in

Chinese organizations with those in Western organizations. Third,

there are other critical factors leading to the job satisfaction or other

important outcome variables. The future research can apply the ideas

of the tetragonal-relationship system and the balance theory to another

context involving other critical factors. Finally, this study was too

deficient in the number of cases to compare all 32 combinations with

respect to the job satisfaction. For enhancing validity of findings, the

future research should expand diverse cases and thus can include all

combinations as analyzing.

References

Agarwal, U. A., Datta, S., Blake-Beard, S., & Bhargava, S. (2012). Linking LMX, innovative

work behaviour and turnover intentions: The mediating role of work engagement.

Career Development International, 17(3), 208–230.

Alessio, J. C. (1990). A synthesis and formalization of Heiderian balance and social

exchange theory. Social Forces, 68(4), 1267–1286.

Amah, O. E. (2009). The direct and interactive roles of work family conflict and work family facilitation in voluntary turnover. International Journal of Human Sciences, 6(2),

812–826.

Aryee, S., & Chen, Z. X. (2006). Leader–member exchange in a Chinese context: Antecedents, the mediating role of psychological empowerment and outcomes. Journal of

Business Research, 59(7), 793–801.

Atwater, L., & Carmeli, A. (2009). Leader–member exchange, feelings of energy, and

involvement in creative work. Leadership Quarterly, 20(3), 264–275.

Awa, H. O., & Nwuche, C. A. (2010). Cognitive consistency in purchase behaviour:

Theoretical & empirical analyses. International Journal of Psychological Studies, 2(1),

44–54.

Baard, P. P., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2004). Intrinsic need satisfaction: A motivational

basis of performance and well-being two work settings. Journal of Applied Social

Psychology, 34(10), 2045–2068.

Basil, D. Z., & Herr, P.M. (2006). Attitudinal balance and cause-related marketing: An

empirical application of balance theory. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 16(4),

391–403.

Basu, R., & Green, S. G. (1997). Leader–member exchange and transformational leadership: An empirical examination of innovative behaviors in leader–member dyads.

Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 27(6), 477–499.

Bauer, T. N., & Green, S. G. (1996). Development of a leader–member exchange: A longitudinal test. Academy of Management Journal, 39(6), 1538–1567.

Berg-Schlosser, D., De Meur, G., Rihous, B., & Ragin, C. C. (2009). Qualitative comparative

analysis (QCA) as an approach. In B. Rihoux, & C. C. Ragin (Eds.), Configurational

comparative methods: Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) and related techniques

(applied social research methods) (pp. 1–18). Thousand Oaks and London: Sage.

Carroll, M. P. (1977). A test of Newcomb's modification of balance theory. Journal of Social

Psychology, 101, 155–156.

Carson, P. P., Carson, K. D., Knouse, S. B., & Roe, C. W. (1997). Balance theory applied to

service quality a focus on the organization, provider, and consumer triad. Journal of

Business & Psychology, 12(2), 99–120.

Cartwright, D., & Harary, F. (1956). Structural balance: A generalization of Heider's theory.

Psychological Review, 63(5), 277–293.

Chih, W. H., & Lin, Y. A. (2009). The study of the antecedent factors of organisational

commitment for high-tech industries in Taiwan. Total Quality Management and

Business Excellence, 20(8), 799–815.

Culbertson, S. S., Huffman, A. H., & Alden-Anderson, R. (2010). Leader–member exchange

and work–family interactions: The mediating role of self-reported challenge- and

hindrance-related stress. Journal of Psychology, 144(1), 15–36.

Davidson, A.R., & Sussmann, M. (1977). Perceived probability and evaluation of balance,

agreement, and attraction: Toward a solution of conflicting results. European Journal

of Social Psychology, 7(4), 433–450.

Dunegan, K. J., Uhl-Bien, M., & Duchon, D. (2002). LMX and subordinate performance: The

moderating effects of task characteristics. Journal of Business & Psychology, 17(2),

275–285.

Farr-Wharton, R., Brunetto, Y., & Shacklock, K. (2011). Professionals' supervisor–subordinate

relationships, autonomy and commitment in Australia: A leader–member exchange

theory perspective. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(17),

3496–3512.

Please cite this article as: Chang, M.-L., & Cheng, C.-F., How balance theory explains high-tech professionals' solutions of enhancing job

satisfaction, Journal of Business Research (2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.10.010

M.-L. Chang, C.-F. Cheng / Journal of Business Research xxx (2013) xxx–xxx

Fried, Y. (1991). Meta-analytic comparison of the job diagnostic survey and job characteristics inventory as correlates of work satisfaction and performance. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 76(5), 690–697.

Frye, N. K., & Breaugh, J. A. (2004). Family-friendly policies, supervisor support, work–

family conflict, family–work conflict, and satisfaction: A test of a conceptual model.

Journal of Business & Psychology, 19(2), 197–220.

Gagné, M. (2003). The role of autonomy support and autonomy orientation in prosocial

behavior engagement. Motivation & Emotion, 27(3), 199–223.

Gagné, M., & Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of

Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 331–362.

Gerstner, C. R., & Day, D.V. (1997). Meta-analytic review of leader–member exchange

theory: Correlates and construct issues. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(6), 827–844.

Glavin, P., & Schieman, S. (2012). Work–family role blurring and work–family conflict:

The moderating influence of job resources and job demands. Work & Occupations,

39(1), 71–98.

Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader–member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 219–247.

Hair, J. F., Black, B., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.)

Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Harris, K. J., & Kacmar, K. M. (2006). Too much of a good thing: The curvilinear effect of

leader–member exchange on stress. Journal of Social Psychology, 146(1), 65–84.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.146.1.65-84.

Harris, K. J., Wheeler, A.R., & Kacmar, K. M. (2009). Leader–member exchange and

empowerment: Direct and interactive effects on job satisfaction, turnover intentions,

and performance. Leadership Quarterly, 20(3), 371–382.

Harris, K. J., Wheeler, A.R., & Kacmar, K. M. (2011). The mediating role of organizational job

embeddedness in the LMX-outcomes relationships. Leadership Quarterly, 22(2), 271–281.

Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York: Wiley.

Hirst, G., Budhwar, P., Cooper, B. K., West, M., Long, C., Chongyuan, X., et al. (2008).

Cross-cultural variations in climate for autonomy, stress and organizational productivity relationships: A comparison of Chinese and UK manufacturing organizations.

Journal of International Business Studies, 39(8), 1343–1358.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress.

American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524.

Hsieh, M. H., & Tsai, K. H. (2007). Technological capability, social capital and the launch

strategy for innovative products. Industrial Marketing Management, 36(4), 493–502.

Kacmar, K. M., Zivnuska, S., & White, C. D. (2007). Control and exchange: The impact of

work environment on the work effort of low relationship quality employees.

Leadership Quarterly, 18(1), 69–84.

Karatepe, O. M., & Uludag, O. (2008). Supervisor support, work–family conflict, and

satisfaction outcomes: An empirical study in the hotel industry. Journal of Human

Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 7(2), 115–134.

Kohli, A. K., Shervani, T. A., & Challagalla, G. N. (1998). Learning and performance orientation

of salespeople: The role of supervisors. Journal of Marketing Research, 35(2), 263–274.

Kossek, E., & Ozeki, C. (1998). Work–family conflict, policies, and the job–life satisfaction

relationship: A review and directions for organizational behavior-human resources

research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(2), 139–149.

Lapierre, L. M., Hackett, R. D., & Taggar, S. (2006). A test of the links between family interference with work, job enrichment and leader–member exchange. Applied

Psychology: An International Review, 55(4), 489–511.

Lee, J. (2008). Effects of leadership and leader–member exchange on innovativeness.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23(6), 670–687.

Major, D. A., Fletcher, T. D., Davis, D.D., & Germano, L. M. (2008). The influence of work–

family culture and workplace relationships on work interference with family: A

multilevel model. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 29(7), 881–897.

Mauno, S., Kinnunen, U., & Ruokolainen, M. (2006). Exploring work- and organization-based

resources as moderators between work–family conflict, well-being, and job attitudes.

Work & Stress, 20(3), 210–233.

McNall, L. A., Nicklin, J. M., & Masuda, A.D. (2010). A meta-analytic review of the consequences associated with work–family enrichment. Journal of Business & Psychology,

25(3), 381–396.

Moreau, E., & Mageau, G. (2012). The importance of perceived autonomy support for the

psychological health and work satisfaction of health professionals: Not only supervisors count, colleagues too! Motivation & Emotion, 36(3), 268–286.

11

Netemeyer, R. G., Boles, J. S., & McMurrian, R. (1996). Development and validation of

work–family conflict and family–work conflict scales. Journal of Applied Psychology,

81(4), 400–410.

Newcomb, T. M. (1968). Interpersonal balance. In R. P. Abelson, E. Aronson, W. J. McGuire,

T. M. Newcomb, M. J. Rosenberg, & P. H. Tannenbaum (Eds.), Theories of cognitive

consistency: A sourcebook (pp. 28–51). Chicago: Rand McNally.

Park, R., & Searcy, D. (2012). Job autonomy as a predictor of mental well-being: The moderating role of quality-competitive environment. Journal of Business & Psychology,

27(3), 305–316.

Price, J. L. (1997). Handbook of organizational measurement. International Journal of

Manpower, 18(4/5/6), 303–558.

Price, K. O., Harburg, E., & Newcomb, T. M. (1966). Psychological balance in situations of

negative interpersonal attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3(3),

265–270.

Qu, H., & Zhao, X. (2012). Employees' work–family conflict moderating life and job satisfaction. Journal of Business Research, 65(1), 22–28.

Raelin, J. A. (1985). The basis for the professional's resistance to managerial control.

Human Resource Management, 24(2), 147–175.

Ragin, C. C. (2008a). Redesigning social inquiry: Fuzzy sets and beyond. Chicago: University

of Chicago Press.

Ragin, C. C. (2008b). User's guide to fuzzy-set/qualitative comparative analysis. Available

online at: www.fsqca.com

Ragin, C. C. (2009). Qualitative comparative analysis using fuzzy sets (fsQCA). In B.

Rihoux, & C. C. Ragin (Eds.), Configurational comparative methods: qualitative

comparative analysis (QCA) and related techniques (applied social research methods)

(pp. 87–121). Thousand Oaks and London: Sage.

Scott, S. G., & Bruce, R. A. (1998). Following the leader in R&D: The joint effect of subordinate problem-solving style and leader–member relations on innovative behavior.

IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 45(1), 3–10.

Spreitzer, G. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions,

measurement and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), 1442–1465.