Hiding Behind Ivory Towers

advertisement

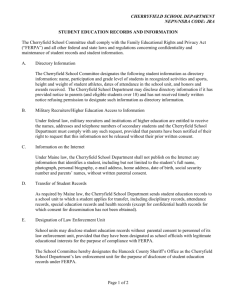

Hiding Behind Ivory Towers: Penalizing Schools That Improperly Invoke Student Privacy To Suppress Open Records Requests ROB SILVERBLATT* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 494 I. GENERAL PRINCIPLES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 496 A. FERPA: AN INTRODUCTION ........................... 496 B. OPEN RECORDS LAWS AND THE SEARCH FOR TRANSPARENCY .... 498 C. FERPA AND OPEN RECORDS LAWS: A COLLISION COURSE ....... 500 II. ABUSES OF FERPA: ORIGINS AND COSTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 502 A. OVERCOMPLIANCE AND INTENTIONAL FLOUTING ............. 502 B. CASE STUDIES: THE PROBLEM IN ACTION .................. 504 Poway Unified School District v. Superior Court (In re Copley Press, Inc.) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 504 Bracco v. Machen . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 505 .............................. 506 III. THE INADEQUACY OF CURRENT PROTECTIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 507 1. 2. C. A. EXPLORING THE COSTS A LOOK AT HOW OPEN RECORDS LAWS CURRENTLY PUNISH ..................................... 507 .................... 508 1. Misaligned Incentives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 508 2. The Special Problem of Student Journalists . . . . . . . . . . 510 IV. FIXING FERPA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 511 VIOLATORS B. A. THE NEED FOR SPECIAL PROTECTIONS THE SPENDING CLAUSE: GENERAL PRINCIPLES .............. 512 * Georgetown University Law Center, J.D. expected 2013; Tufts University, B.A. 2009. © 2013, Rob Silverblatt. Special thanks to Professor Ken Jost for his free-press seminar, which inspired this paper. Most of all, I would like to thank my parents, Susan and Arthur Silverblatt, without whose support none of this would have been possible. 493 494 THE GEORGETOWN LAW JOURNAL B. APPLYING THE TEST C. CALIBRATING THE PENALTIES D. CHOOSING A STANDARD [Vol. 101:493 ................................ 514 ......................... 515 ............................. 516 CONCLUSION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 517 INTRODUCTION The University of North Carolina’s football team was reeling from accusations of widespread ethical lapses, and Butch Davis, the once-celebrated squad’s coach, stood right at the center of the mounting controversy. For Davis, 2010 was a brutal year. The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) was investigating several members of his team; one of his star players was making national headlines for allegedly receiving improper benefits during trips to Miami and California; and sports fans were calling for Davis’s head.1 As accusations swirled, journalists descended onto the school’s Chapel Hill campus looking for proof of wrongdoing.2 They sought public records, but what they got instead was a five-letter acronym: FERPA.3 The University contended that the records requested, which included parking tickets and Davis’s phone logs, were exempt from disclosure under the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA),4 which penalizes educational institutions that have a policy or practice of releasing “education records” to unauthorized third parties.5 Despite convincing evidence to the contrary, the University continued to press the position that the information sought constituted education records.6 The next year, following a suit to compel UNC to release the records, the presiding judge chastised the university and reminded its administrators that federal law does not allow them to cover their campus with “an invisible cloak.”7 The judge then ordered the release of the phone logs and the tickets.8 FERPA, the brainchild of then-Senator James Buckley, is a 1974 law with a common-sense purpose. It was meant to keep academic information, such as grades and transcripts, accessible to students and their parents and private from 1. See, e.g., Justin Eisenband, North Carolina Tarheels Scandal: Marvin Austin and Co. Suspended for Entire Year, BLEACHER REP. (Oct. 11, 2010), http://bleacherreport.com/articles/488187-north-carolinascandal-austin-quinn-little-all-suspended-for-season; Terence Moore, North Carolina’s Butch Davis Has To Go—And Now, AOL NEWS (Sept. 5, 2010, 1:40 AM), http://www.aolnews.com/2010/09/05/northcarolinas-butch-davis-has-to-go-and-now/. 2. See Sarah Frier, Lawsuit Decision Is a Call for Openness, DAILY TAR HEEL (Apr. 20, 2011, 11:27 AM), http://www.dailytarheel.com/index.php/article/2011/04/lawsuit_decision_is_a_call_for_openness. 3. Id. 4. 20 U.S.C. § 1232g (2006). 5. See Frier, supra note 2. 6. See id. 7. See News & Observer Publ’g Co. v. Baddour, No. 10-CVS-1941, slip op. at 2 (N.C. Super. Ct. Apr. 19, 2011) (memorandum opinion). 8. Id. at 2–3. 2013] HIDING BEHIND IVORY TOWERS 495 just about everyone else.9 Watergate had recently shaken the nation’s confidence, and privacy concerns were a top priority among legislators.10 At the time, the proposal made perfect sense to Buckley. Now, however, as schools have begun routinely using FERPA to deny valid requests for information, he fears that the situation has gotten out of hand.11 “One thing I have noticed,” Buckley told a newspaper in 2011, “is a pattern where the universities and colleges have used [FERPA] as an excuse for not giving out any information they didn’t want to give.”12 Every state has an open records law that makes certain information a matter of public record and prescribes steps that journalists and ordinary citizens must follow to request and obtain documents.13 These laws are meant to promote openness and transparency and are considered by state governments to be central to the proper functioning of a representative democracy.14 But over the past several years, these open records laws have increasingly been stymied by educational institutions that have unlawfully withheld documents, often citing FERPA as their rationale even though the information in question bears little resemblance to an education record.15 While FERPA arguably overrides these laws in the case of actual education records,16 it has been invoked in almost every imaginable context. Open records advocates have bemoaned this trend, claiming that FERPA has been “twisted beyond recognition.”17 These complaints, however, have largely gone unheeded. This Note suggests that the reason for this is that the status quo gives institutions strong incentives to unlawfully deny open records requests through reliance on FERPA. Indeed, it makes economic sense for many of these institutions to overcomply with FERPA and undercomply with open records laws. To alleviate this problem, this Note proposes the imposition of penalties on schools that unreasonably withhold documents in response to open records requests. Part I sets forth an introduction to FERPA and the various open records laws that currently exist. It explains how FERPA and open records laws interact and provides background about the conflicts that frequently result when schools decline to produce documents in response to requests from journalists. Part II explores how FERPA has been abused and provides case studies illustrating the 9. See infra section I.A. 10. See generally Mary Margaret Penrose, In the Name of Watergate: Returning FERPA to Its Original Design, 14 N.Y.U. J. LEGIS. & PUB. POL’Y 75 (2011) (discussing the background against which FERPA was enacted). 11. It’s Clear the ‘O’ Stands for Opaque, REGISTER-GUARD (Feb. 18, 2011), http://special.registerguard. com/csp/cms/sites/web/sports/25904339-41/records-public-ncaa-oregon-ferpa.csp. 12. Id. (internal quotation marks omitted). 13. Daxton R. “Chip” Stewart, Let the Sunshine in, or Else: An Examination of the “Teeth” of State and Federal Open Meetings and Open Records Laws, 15 COMM. L. & POL’Y 265, 265 (2010). 14. See infra section I.B. 15. See infra Part II. 16. See infra section I.C. 17. See Reporter’s Guide to FERPA: Navigating the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, SOC’Y OF PROF. JOURNALISTS, http://www.spj.org/ferpa.asp (last visited May 1, 2012). 496 THE GEORGETOWN LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 101:493 tension between privacy and transparency. Part III examines how open records laws currently punish the wrongful withholding of documents and makes the case that the available options fail to provide a reasonable check against schools’ abuses of FERPA. Finally, Part IV suggests that Congress amend FERPA to provide for penalties against schools that unreasonably refuse to comply with open records requests. Specifically, this Note calls for Congress to use its power under the Constitution’s Spending Clause18 to withhold a fixed percentage of a school’s federal funding each time the school, without any reasonable basis in the law, misclassifies a document as an education record in response to a valid open records request. This is functionally a negligence standard, and it allows institutions to escape penalties if they wrongfully, although not unreasonably, withhold documents. The determination of the reasonableness of the withholding would be made by the Department of Education’s Family Policy Compliance Office, which is the division currently tasked with administering FERPA. While this Note suggests leaving the precise amount of the penalties for Congress to determine, it provides guidance that legislators should consider when calibrating them. Ultimately, this Note contends that instituting penalties would remedy the broken incentive structure and encourage good-faith compliance with open records laws. I. GENERAL PRINCIPLES On their surfaces, FERPA and open records laws have countervailing purposes. FERPA conditions educational institutions’ federal funding on their ability to keep students’ academic records out of the hands of most third parties. Open records laws, on the other hand, require the release of a whole host of documents to those who request them. Where FERPA values privacy, open records laws promote transparency. As such, it is not surprising that there has historically been tension between the two regimes. This Part explores that friction. Section A provides background on the goals and administration of FERPA. Section B provides similar information about federal and state open records laws. Section C discusses how these various provisions interact. A. FERPA: AN INTRODUCTION At its core, FERPA is concerned with two ideals: promoting the ability of parents to access students’ records and maintaining the privacy of those records vis-à-vis outsiders.19 Importantly, FERPA does not create any rights for par- 18. U.S. CONST. art. 1, § 8, cl. 1. 19. See, e.g., Ralph D. Mawdsley & Charles J. Russo, FERPA, Student Privacy and the Classroom: What Can Be Learned from Owasso School District v. Falvo?, 171 WEST’S EDUC. L. REP. 397, 398 (2003). 2013] HIDING BEHIND IVORY TOWERS 497 ents.20 Instead, FERPA leverages Congress’s spending power to deny federal funding to institutions that fail to properly handle students’ records. As such, any educational institution that has a policy of interfering with parents’ ability to “inspect and review” their childrens’ “education records” is ineligible for federal funding.21 Similarly, with respect to individuals other than students’ parents, no federal funding is available to an institution “which has a policy or practice of permitting the release of education records (or personally identifiable information contained therein other than directory information . . .) of students” without either parental consent or a judicial order.22 It is unclear how many times an institution must release education records before a “policy or practice” can be found, but a single violation is certainly insufficient.23 Although the legislation refers primarily to parents, when a student turns eighteen or begins to attend a postsecondary institution, he obtains exclusive control of the protections otherwise afforded to parents.24 Under FERPA, the central question for administrators is often how broadly to interpret the term “education record.” The legislation defines the term as “records, files, documents, and other materials” that “contain information directly related to a student” and “are maintained by an educational agency or institution or by a person acting for such agency or institution.”25 The Supreme Court has interpreted the word “maintained” narrowly, remarking, “FERPA implies that education records are institutional records kept by a single central custodian, such as a registrar . . . .”26 There is broad agreement among courts that institutions can, and often must, disclose documents with personally identifiable student information so long as that information, if it is protected by FERPA, is redacted.27 Meanwhile, under FERPA, several classes of documents explicitly do not qualify as “education records.” The most notable exemption is for “records maintained by a law enforcement unit of the educational agency or 20. See Gonzaga Univ. v. Doe, 536 U.S. 273, 290 (2002) (holding that there is no private right of action available under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 to enforce violations of FERPA). 21. 20 U.S.C. § 1232g(a)(1)(A) (2006). 22. Id. § 1232g(b)(1). Directory information includes the following: “the student’s name, address, telephone listing, date and place of birth, major field of study, participation in officially recognized activities and sports, weight and height of members of athletic teams, dates of attendance, degrees and awards received, and the most recent previous educational agency or institution attended by the student.” Id. § 1232g(a)(5)(A). Parents can opt out of having this information subject to release. Id. § 1232g(a)(5)(B). Certain other individuals also have access to education records under limited circumstances. See, e.g., id. §§ 1232g(b)(1)(A)–(K). 23. See Gonzaga, 536 U.S. at 288 (“FERPA’s nondisclosure provisions . . . speak only in terms of institutional policy and practice, not individual instances of disclosure.”). 24. 20 U.S.C. § 1232g(d) (2006). 25. Id. § 1232g(a)(4)(A). 26. Owasso Indep. Sch. Dist. v. Falvo, 534 U.S. 426, 434–35 (2002). 27. See, e.g., Unincorporated Operating Div. of Ind. Newspapers, Inc. v. Trs. of Ind. Univ., 787 N.E.2d 893, 908 (Ind. Ct. App. 2003). 498 THE GEORGETOWN LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 101:493 institution that were created by that law enforcement unit for the purpose of law enforcement.”28 To date, no institution has lost funding as a result of FERPA violations.29 Nonetheless, FERPA’s impact on the nation’s educational system is hard to underestimate. Almost all schools, from preschools to graduate schools, depend largely on federal funding and are therefore within FERPA’s reach.30 As one commentator observed, “[f]ew other laws have affected the daily administration of schools and colleges as much as FERPA.”31 B. OPEN RECORDS LAWS AND THE SEARCH FOR TRANSPARENCY All fifty states, as well as the District of Columbia and the federal government, have open records laws.32 By far the most well-known is the federal Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).33 However, FOIA applies only to federal agencies,34 so the statute has largely been absent from the discussion of FERPA, which pertains to educational institutions. Consequently, FERPA and “right to know” doctrines have interacted—and collided—almost exclusively in the arena of state open records statutes. One unifying theme among state open records laws is that state legislatures view them as central to the proper functioning of a representative democracy, and as such they are willing to afford strong presumptions in favor of information being publicly accessible.35 Nonetheless, the relationship between open records laws and educational institutions varies substantially from state to 28. 20 U.S.C. § 1232g(a)(4)(B)(ii) (2006). 29. See Jill Riepenhoff & Todd Jones, Secrecy 101: A Dispatch Investigation Shows Many College Athletic Departments Nationwide Use a Vague Federal Law To Keep Public Records from Being Seen, COLUMBUS DISPATCH, May 31, 2009, at A1. 30. Thomas R. Baker, State Preemption of Federal Law: The Strange Case of College Student Disciplinary Records Under F.E.R.P.A., 149 WEST’S EDUC. L. REP. 283, 285 (2001) (“With virtually every educational institution in the nation dependent upon federal funds, FERPA in effect became the law of the land for school administrators.”). 31. Id. at 283. 32. See Stewart, supra note 13, at 265. 33. 5 U.S.C. § 552 (2006). 34. See id. § 552(a); see also Lisa A. Krupicka & Mary E. LaFrance, Note, Developments Under the Freedom of Information Act—1984, 1985 DUKE L.J. 742, 774–75. 35. See, e.g., S.C. CODE ANN. § 30-4-15 (2007) (“The General Assembly finds that it is vital in a democratic society that public business be performed in an open and public manner so that citizens shall be advised of the performance of public officials and of the decisions that are reached in public activity and in the formulation of public policy. Toward this end, provisions of this chapter must be construed so as to make it possible for citizens, or their representatives, to learn and report fully the activities of their public officials at a minimum cost or delay to the persons seeking access to public documents or meetings.”); TEX. GOV’T CODE ANN. § 552.001 (West 2004) (“Under the fundamental philosophy of the American constitutional form of representative government that adheres to the principle that government is the servant and not the master of the people, it is the policy of this state that each person is entitled, unless otherwise expressly provided by law, at all times to complete information about the affairs of government and the official acts of public officials and employees. . . . The provisions of this chapter shall be liberally construed to implement this policy.”). 2013] HIDING BEHIND IVORY TOWERS 499 state.36 As a preliminary matter, open records laws typically do not affect private colleges.37 Public schools, by contrast, are typically covered by open records laws, although some states’ laws are written such that their application to certain educational institutions is unclear.38 However, even in states that do subject certain publicly funded institutions to open records laws, there can be anomalies. Take, for instance, Penn State University, which was recently besieged by a sex-abuse scandal.39 Revelations of child molestation perpetrated by Jerry Sandusky, a former assistant coach of the famed Nittany Lions football program, led to a number of dramatic consequences. University President Graham Spanier resigned in disgrace.40 Iconic coach Joe Paterno was fired, and a statue of him was unceremoniously removed from schools grounds.41 Sandusky was convicted in court.42 And the NCAA slapped the University with a $60 million fine.43 Amidst all of those changes, however, one thing has remained the same: Pennsylvania’s lackluster open records law. Under Pennsylvania’s open records law, Penn State and three other schools are legislatively “exempt from the open-records law that applies to Pennsylvania’s 14 public universities.”44 That is because Penn State is considered a “[s]tate-related institution.”45 As such, while it is subject to certain reporting 36. Part of this variation results from the differing degrees of effectiveness among the state laws. There have been a number of studies that have examined the substantive provisions of the various open records laws. These studies do not relate specifically to how the laws apply to schools but instead measure the general effectiveness of the provisions. In one study, the Better Government Association gave grade-point averages to the laws of all fifty states and the District of Columbia. Nebraska, with a 3.3 GPA (nearly a B⫹), came in first, whereas Alabama and South Dakota received failing grades. See Bill F. Chamberlin et al., Essay, Searching for Patterns in the Laws Governing Access to Records and Meetings in the Fifty States by Using Multiple Research Tools, 18 U. FLA. J.L. & PUB. POL’Y 415, 421–22 (2007). 37. See SPLC Tip Sheet: Access to University Foundation Records, STUDENT PRESS LAW CTR., http://www.splc.org/knowyourrights/legalresearch.asp?id⫽110 (last visited July 23, 2012). 38. See Universities, Hospitals and Other Publicly Funded Institutions Are Often Subject to FOIA Laws, VR RES. BLOG (Jan. 14, 2010), http://vrresearch.com/blog/?p⫽668 (dividing state laws into baskets based on how explicitly they cover publicly funded institutions). 39. See Bill Chappell, Penn State Abuse Scandal: A Guide and Timeline, NPR (June 21, 2012), http://www.npr.org/2011/11/08/142111804/penn-state-abuse-scandal-a-guide-and-timeline. 40. See, e.g., Paula Reed Ward, Spanier Drops Lawsuit Against Penn State, PITTSBURGH POSTGAZETTE (July 19, 2012), http://www.post-gazette.com/stories/local/state/spanier-drops-lawsuit-againstpenn-state-645234/. 41. Chris Dufresne, Paterno Statue Comes Down a Day Before NCAA’s Hammer, CHI. TRIB. (July 22, 2012), http://www.chicagotribune.com/sports/college/ct-spt-0723-penn-state--20120723,0,5457786. story. 42. Jury Convicts Jerry Sandusky, ESPN.COM (June 23, 2012, 2:29 PM), http://espn.go.com/collegefootball/story/_/id/8087028/penn-state-nittany-lions-jerry-sandusky-convicted-45-counts-sex-abusetrial. 43. Edith Honan, Penn State Hit with Unprecedented Penalties for Sandusky Scandal, REUTERS (July 23, 2012), http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/07/23/us-usa-pennstate-idUSBRE86L07F20120723. 44. Nathan Fenno, Penn State’s Exemption in State Law Limits Probe, WASH. TIMES (Dec. 6, 2011), http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2011/dec/6/penn-states-exemption-in-state-law-limits-probe/ ?page⫽all. 45. 65 PA. STAT. ANN. § 67.102 (West 2010). 500 THE GEORGETOWN LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 101:493 requirements,46 it does not need to respond to open records requests from members of the public.47 Critics have argued that without this exemption, the scandal would have come to light far sooner than it actually did.48 While the Penn State example demonstrates how substantive provisions can matter, procedural variations are what account for most of the differences among states. In Minnesota, Michigan, and Wisconsin, institutions that violate open records requirements can face punitive damages.49 While most states have explicit statutory provisions governing the collection of attorney’s fees in open records cases, six states—Alabama, Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, South Dakota, and Wyoming—do not.50 On other issues, jurisdictions are divided more evenly. For instance, twenty states provide for civil fines or forfeitures for open records violations, but the laws in thirty-two jurisdictions (including the federal government and the District of Columbia) do not have such provisions.51 Despite these differences, a common theme is that state legislatures are typically conscious of potential conflicts between open records laws and the various privacy laws that exist at the state and federal levels. As such, a common provision in states’ open records laws is an exception for information that is deemed confidential under another law.52 C. FERPA AND OPEN RECORDS LAWS: A COLLISION COURSE Conflicts between FERPA and states’ open records laws “frequently arise.”53 Indeed, the relationship between FERPA on the one hand and open records laws on the other is fraught with “tension . . . between two core democratic concepts— individual privacy and the public’s right to know about the government’s activities.”54 Typically, this tension arises when a journalist files an open records request with an educational institution and the institution declines to comply on the ground that FERPA purportedly bars disclosure. For example, 46. See id. § 67.1503. 47. See id. § 67.301 (noting the law’s applicability to “Commonwealth agenc[ies]”); id. § 67.102 (defining the term “Commonwealth agency”). 48. See, e.g., Al Tompkins, How Open Records Law Would Have Stopped Sex Abuse Sooner at Penn State, POYNTER INST. (July 13, 2012), http://www.poynter.org/latest-news/als-morning-meeting/180740/ would-open-records-have-stopped-abuse-sooner-at-penn-state/. 49. See Stewart, supra note 13, at 280. 50. Id. at 282 & n.117. 51. Id. at 286 & n.150. 52. See, e.g., Baker, supra note 30, at 294 (“Fortunately for students and administrators, state legislators who drafted public records laws sought to avoid conflicts between federal law and state law. When a state open records law operated at cross-purposes with a federal law, lawmakers conceded in advance that the conflict would be resolved in favor of applicable federal law. This they did by inserting a specific exception in the state law for records defined as private under federal law.”). 53. Sunshine Law News: Public Disclosure Obligations and Student Records, OFFICE OF OHIO ATT’Y GEN. MIKE DEWINE (July 6, 2011), http://www.ohioattorneygeneral.gov/Briefing-Room/Newsletters/Legalnews/July-2011/Public-Disclosure-Obligations-and-Student-Records [hereinafter Sunshine Law News]. 54. Mathilda McGee-Tubb, Note, Deciphering the Supremacy of Federal Funding Conditions: Why State Open Records Laws Must Yield to FERPA, 53 B.C. L. REV. 1045, 1051 (2012). 2013] HIDING BEHIND IVORY TOWERS 501 when the Chicago Tribune filed an Illinois Freedom of Information Act55 request seeking information about the role that legacy status played in the admissions process at the University of Illinois, the University claimed that FERPA barred the release of the relevant documents.56 FERPA, of course, does not apply to each and every piece of information in an educational institution’s possession. Accordingly, upon receiving an open records request, institutions must generally make good-faith efforts to comply.57 This involves turning over documents that are not education records (and are not otherwise protected) and redacting education records to remove personally identifiable student information while still releasing the nonprotected portions.58 When the process breaks down between requesters and educational institutions, the courts must step in to referee. Courts must resolve whether the information sought constitutes an education record and, if so, whether it can nonetheless be released. As to the former question, the courts all agree that if a document is not an education record, FERPA does not apply.59 Thus, the case law is replete with examples of judges ordering the release of information on the ground that an institution misclassified documents as education records.60 However, in the event that the requester is seeking access to a bona fide education record, courts are split on how to resolve the tension between the right to know under open records laws and the privacy enshrined by FERPA.61 However, since this Note is concerned with institutions that negligently misclassify documents as education records, there is no need at the present moment to resolve the conflicting approaches to the release of actual education records. 55. See 5 ILL. COMP. STAT. 140/1–140/11.5 (2011). 56. See Chi. Trib. Co. v. Univ. of Ill. Bd. of Trs., 781 F. Supp. 2d 672, 673–74 (N.D. Ill. 2011). 57. See, e.g., Sunshine Law News, supra note 53. 58. Id. 59. See generally Owasso Indep. Sch. Dist. v. Falvo, 534 U.S. 426, 428–31 (2002) (discussing the contours of FERPA and the definition of the term “education record.”). 60. See Brief for Reporters Comm. for Freedom of the Press et al. as Amici Curiae Supporting Appellee at 1–2, Chi. Trib. Co. v. Univ. of Ill. Bd. of Trs., 680 F.3d 1001 (7th Cir. 2012) (No. 11-2066) (collecting cases). 61. This frequently involves weighing the language of FERPA against a state open records exception shielding information that must be kept private under other applicable law. In Illinois, for instance, the state’s act exempts from disclosure “[i]nformation specifically prohibited from disclosure by federal or State law or rules and regulations implementing federal or State law.” 5 ILL. COMP. STAT. 140/7(1)(a) (2011). In the Chicago Tribune’s lawsuit seeking information about legacy admissions, the court ruled that even if the documents constituted education records, FERPA could not serve as a justification for withholding them because, although FERPA can cause educational institutions to lose money, it does not “specifically prohibit[]” them from releasing information. Chi. Trib. Co., 781 F. Supp. 2d at 675–77. Other courts interpreting similar open records statutes have expressed skepticism toward this approach and have taken the position that FERPA functionally requires schools to keep education records confidential, thereby making FERPA a trump card in open records disputes. See, e.g., Unincorporated Operating Div. of Ind. Newspapers, Inc. v. Trs. of Ind. Univ., 787 N.E.2d 893, 904 (Ind. Ct. App. 2003) (“[I]f we were to hold . . . that FERPA was not a federal law requiring education records to be kept confidential, public disclosure of such materials could soon become a commonplace occurrence.”). 502 THE GEORGETOWN LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 101:493 II. ABUSES OF FERPA: ORIGINS AND COSTS Over the past several years, institutions’ use of FERPA has come under fire from a variety of sources, including journalists, lawyers, judges, and even the legislation’s own author. Section A focuses on the two most common criticisms. The first is overcompliance with FERPA, which happens when administrators who do not fully understand the legislation’s guidelines assert FERPA in response to open records requests. The second is intentional flouting, which occurs when institutions use FERPA as a shield to guard against the release of embarrassing documents. Next, section B uses case studies to illustrate how these problems materialize in actual litigation. This Part concludes with an analysis of the costs of these two problems: namely, the litigation of unnecessary lawsuits and the suppression, or at the very least the delayed release, of information of acute public interest. A. OVERCOMPLIANCE AND INTENTIONAL FLOUTING Frank LoMonte, the executive director of the Student Press Law Center (SPLC), has watched the evolution of FERPA with a keen interest, observing that, nationally, there is a “severe overcompliance issue.”62 The SPLC, which devotes a portion of its website to educating student journalists about FERPA and open records laws, cites as examples the University of Wisconsin’s withholding of minutes from public meetings and a number of universities’ refusal to release the names of people who were given free football tickets.63 Former Senator Buckley, who after leaving Congress went on to serve as a judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, has bemoaned the approach that schools have adopted toward FERPA. Buckley, who authored FERPA in 1974, has complained that “[t]hings have gone wild . . . . One likes to think common sense would come into play. Clearly, these days, it isn’t true.”64 In particular, Buckley faulted institutions for “putting their own meaning into the law.”65 Often, that meaning translates into blanket denials of media requests for information. For instance, David Chartrand, a humorist and commentator from Kansas, recalls an official at a local junior high school asserting FERPA in response to his request to see one of the school’s lunch menus.66 Frequently, it is difficult to ascertain whether unlawful withholding is motivated by confusion, 62. Lee Rood, U of I Wants Clarification After Request for Records, DES MOINES REGISTER (Oct. 22, 2008), http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/desmoinesregister/access/1695736511.html?FMT⫽ABS&FMTS⫽ ABS:FT. 63. See FERPA and Access to Public Records, STUDENT PRESS LAW CTR., http://www.splc.org/pdf/ ferpa_wp.pdf (last visited May 1, 2012). 64. Riepenhoff & Jones, supra note 29. 65. Id. 66. See David Chartrand, FERPA Tales: It Doesn’t Always Apply, SOC’Y OF PROF. JOURNALISTS, http://www.spj.org/ferpa5.asp (last visited May 1, 2012) (“Using the federal Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act to dodge journalists has become a highly skilled sport among those who manage the 2013] HIDING BEHIND IVORY TOWERS 503 inadequate attempts to ascertain the meaning of FERPA, or a desire to keep embarrassing information from seeing the light of day. In many instances, however, free-press advocates have observed what they perceive to be an intentional flouting of the law by school administrators. For instance, a large group of media organizations, acting collectively as amici curiae in the Supreme Court’s review of the University of Illinois legacy-admissions case,67 pointedly accused the university of “cr[ying] ‘student privacy’ in an attempt to frustrate public disclosure of information reflecting unflatteringly on the conduct of the university’s administrators.”68 Similarly, Sonny Albarado, the president of the Society of Professional Journalists, has accused institutions of “hiding behind [FERPA] rather than opting for openness.”69 Mary Margaret Penrose, an education law expert at the Texas Wesleyan School of Law, has written extensively about the abuses associated with the so-called “FERPA defense.”70 Penrose has noted that universities “regularly invoke FERPA in response to open-record requests or press inquiries where the information sought places the institution in a negative light. The goal is non-disclosure. The chorus is student privacy. The tool: the FERPA defense.”71 Penrose argues that this “FERPA chimera is intended to distract us from the bad things happening at universities”72 and contends that many times, the “resort to FERPA is not truly to advance ‘student privacy,’ but [is] rather a convenient defense to salvage the school’s own reputation.”73 There have been very few attempts to track with any precision the extent of such abuse at the national level. Instead, most of the evidence is anecdotal and incapable of being reduced to statistics: the Montana school that unlawfully denied a newspaper’s request for redacted information on the punishments for two students who shot fellow students with BB guns,74 or an Arizona school district’s unlawful withholding of settlement information after a student had been illegally strip-searched by school officials.75 Perhaps the most thorough attempt to date at gauging the overcompliance problem came as part of a 2009 flow of information at American schools and universities. ‘FERPA’ continues the American tradition of turning nouns and proper names into active verbs.”). 67. See supra note 56 and accompanying text. 68. Brief for Reporters Comm. for Freedom of the Press et al. as Amici Curiae Supporting Appellee, supra note 60, at 1. 69. Sonny Albarado, FERPA Often Misconstrued, SOC’Y OF PROF’L JOURNALISTS, http://www.spj.org/ ferpa2.asp (last visited May 1, 2012). 70. See, e.g., Mary Margaret Penrose, Tattoos, Tickets, and Other Tawdry Behavior: How Universities Use Federal Law To Hide Their Scandals, 33 CARDOZO L. REV. 1555, 1557 (2012). 71. Id. (footnotes omitted). 72. Id. at 1570. 73. Id. at 1562. 74. See Scott Sternberg, Montana Supreme Court Rules School Board Should Have Released Records of Disciplinary Action, STUDENT PRESS LAW CTR. (May 16, 2007), http://www.splc.org/news/ newsflash.asp?id⫽1518. 75. See Peter Velz, Judge Orders Release of Settlement Agreement in ‘Strip Search’ Case That Went to Supreme Court, STUDENT PRESS LAW CTR. (Sept. 16, 2011), http://www.splc.org/news/newsflash.asp? id⫽2276. 504 THE GEORGETOWN LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 101:493 investigation by the Columbus Dispatch into the use of FERPA in the universe of college athletics.76 The newspaper sent document requests to 119 colleges, seeking records such as flight manifests and ticket information for sports teams, as well as information regarding NCAA violations.77 The results were telling: fifty of the schools did not provide any information, and, of the ones that did respond, approximately half censored their flight manifests, which even under the broadest interpretation of FERPA would not qualify as education records.78 B. CASE STUDIES: THE PROBLEM IN ACTION The cases below provide two examples of instances in which a court has unabashedly criticized a school for its reliance on FERPA. Although there is no guarantee that these withholdings would, under the system proposed by this Note, result in penalties, they provide prime examples of the types of behavior that should, at the very least, be subject to further review by the Department of Education’s Family Policy Compliance Office. 1. Poway Unified School District v. Superior Court (In re Copley Press, Inc.)79 Poway has its origins in a savage assault perpetrated by three sixteen-year-old sophomores at a high school in California’s Poway Unified School District.80 In March 1997, the students sodomized a freshman at the school with a broomstick.81 The case garnered significant attention in the media and resulted in the three sophomores pleading guilty in juvenile court.82 Meanwhile, the victim’s attorney alerted the school district to a potential lawsuit under the California Tort Claims Act,83 which led to a settlement between the victim and the district.84 Separately, one of the perpetrators filed a claim against the school district under the same act.85 As part of its coverage of the incident, the San Diego Union-Tribune86 filed a request under California’s Public Records Act to obtain access to all Claims Act documents filed with the school district during a roughly four-month period in 1997.87 76. Riepenhoff & Jones, supra note 29. 77. Id. 78. See id. 79. 73 Cal. Rptr. 2d 777 (Ct. App. 1998) 80. Id. at 780. 81. Id. 82. Id. 83. Id.; see also CAL. GOV’T CODE §§ 810–996.6 (West 2012) (setting forth requirements for suing a government entity for damages). 84. Poway, 73 Cal. Rptr. 2d at 780. 85. Id. 86. The paper now goes by the name U-T San Diego. 87. Poway, 73 Cal. Rptr. 2d at 780; see also CAL. GOV’T CODE §§ 6250–6276.48 (West 2008). 2013] HIDING BEHIND IVORY TOWERS 505 The district declined to provide the information, citing FERPA and FERPA’s California counterpart88 as one of its primary reasons, and the newspaper’s publisher brought suit.89 After losing in the trial court, on appeal the district repeated its contention that the Claims Act documents constituted education records (or, in the parlance of the California counterpart to FERPA, “pupil records”).90 The appellate court summarily rejected this contention, concluding: “It defies logic and common sense to suggest that a Claims Act claim, even if presented on behalf of a student, is an ‘educational record’ or ‘pupil record’ within the purview of these exemptions.”91 Moreover, the court noted, the mere fact that “a litigant has chosen to sue a school does not transmogrify the Claims Act claim into such a record.”92 2. Bracco v. Machen93 Frank Bracco, at the time a student at the University of Florida, received a paradoxical response when he sought to obtain recordings of public meetings of the school’s student senate. The University told him he was allowed to listen to the recordings in the senate office, but because of the school’s purported FERPA obligations, he was not permitted to obtain copies of the recordings.94 Bracco wanted to post the copies online to increase the transparency of the student government.95 After the University repeatedly denied his requests, he filed suit in August 2009 under Florida’s Public Records Act,96 and the University responded by asserting FERPA.97 The trial court, in its findings of fact, made a number of observations which serve to underscore the bizarre nature of the University’s FERPA claim. The court noted, for instance, that the student senate meetings were open to the public.98 Meanwhile, even as the university continued to withhold copies of all of the recordings sought, recordings of two of the senate meetings were available on the University’s website.99 Finally, although the University claimed that releasing the recordings would violate the student senators’ privacy under FERPA, the University’s website contained summaries of the meetings which referenced student participants by name.100 88. CAL. EDUC. CODE § 49061 (West 2006). 89. Poway, 73 Cal. Rptr. 2d at 780. 90. Id. at 780–84. 91. Id. at 784. 92. Id. 93. No. 01-2009-CA-4444, slip op. (Fla. Cir. Ct. Jan. 10, 2011) (order granting plaintiff’s motion for summary judgment). 94. Id. at 1–2. 95. Kyle McDonald, Court: UF Student Senate Records Not Covered by FERPA, STUDENT PRESS LAW CTR. (Jan. 19, 2011), http://www.splc.org/news/newsflash.asp?id⫽2181. 96. FLA. STAT. ANN. §§ 119.01–.15 (West 2008). 97. Bracco, No. 01-2009-CA-4444, at 1–2. 98. Id. at 2. 99. Id. at 3. 100. Id. 506 THE GEORGETOWN LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 101:493 Given these anomalies, the court quickly dispensed with the university’s FERPA arguments, calling them “hardly logical.”101 In particular, the court noted that it was “inconsistent for the Defendant to release certain student government records . . . while holding that video recordings of the same student senate meetings are exempt from disclosure under FERPA . . . .”102 However, the ruling was not released until January 2011, approximately seventeen months after Bracco initially filed suit. By that time, Bracco had already graduated from the University.103 C. EXPLORING THE COSTS The main result of the current state of FERPA compliance is that information that universities are legally required to release under state open records laws often becomes public only after a long delay—if at all. Litigation, even when the issues of law are clear, can be a lengthy process, as the Bracco case demonstrates. This is particularly problematic given the heightened public interest in much of this information. The Columbus Dispatch, in its investigation into schools’ use of FERPA, provides an example of the stakes at issue.104 For instance, only ten percent of universities that responded provided unedited reports of NCAA violations.105 “No one disputes that grades are and should be private. But today, privacy is extended to athletes who have gambled, accepted payoffs, cheated, cashed in on their notoriety, and even sexually abused others,” the newspaper concluded.106 Given universities’ aggressive, and oftentimes unlawful, use of FERPA, it is “virtually impossible to decipher what is going on inside a $5 billion college-sports world that is funded by fans, donors, alumni, television networks and, at most schools, taxpayers.”107 There are also institutional costs to allowing schools to shield their inner workings from the public. Indeed, it enshrines the very secrecy that FERPA, through its requirement that parents be allowed to access students’ records, sought to avoid. As one court noted in rejecting a school’s reliance on FERPA: “Prohibiting disclosure of any document containing a student’s name would allow universities to operate in secret, which would be contrary to one of the policies behind the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act.”108 101. 102. 103. 104. 105. 106. 107. 108. Id. at 5. Id. McDonald, supra note 95. See supra notes 76–78 and accompanying text. Riepenhoff & Jones, supra note 29. Id. See id. Kirwan v. The Diamondback, 721 A.2d 196, 204 (Md. 1998). 2013] HIDING BEHIND IVORY TOWERS 507 III. THE INADEQUACY OF CURRENT PROTECTIONS This Part demonstrates why the current regime provides an inadequate check against the abuses that have been proliferating. Section A explores some of the penalties that can currently be imposed against institutions that unlawfully withhold information in response to valid open records requests. Section B explains why the current penalty structures fail to properly incentivize compliance with open records laws. In particular, FERPA presents a special case of misaligned incentives, and that problem cannot be adequately remedied using existing procedures. Meanwhile, the frequent involvement of student journalists in FERPA-related open records cases raises concerns that are not present in most open records disputes. Because of the unique issues that these student journalists present, special protections are more readily justifiable. A. A LOOK AT HOW OPEN RECORDS LAWS CURRENTLY PUNISH VIOLATORS Imposing penalties for noncompliance with open records laws is hardly a novel concept. Indeed, most laws of this variety allow for penalties when records are improperly withheld.109 Nonetheless, over time, one of the most common criticisms of open records laws has been that they are toothless, and, as such, there have been frequent calls for reforming the penalties associated with withholding documents. Such criticisms have often targeted the federal Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), the sanctions provision of which is rarely invoked by courts.110 Under FOIA, an agency employee can be sanctioned for withholding documents if: (1) the court orders production of the documents; (2) the court orders attorney’s fees against the government; (3) the court finds reason to believe the agency employee acted arbitrarily or capriciously in withholding the information; and (4) a subsequent investigation leads to a recommendation for the imposition of a sanction.111 Echoing a frequent refrain, one commentator noted that this system “has proved to be an almost insurmountable barrier for FOIA plaintiffs.”112 Litigants at the state level generally fare better than their federal counterparts. Indeed, whereas FOIA merely authorizes “disciplinary action” against the employee responsible for withholding records, twenty jurisdictions explicitly allow for civil fines or forfeitures for violations of open records laws.113 However, in 109. See Stewart, supra note 13, at 286–98 (surveying various jurisdictions’ penalty provisions). 110. See Paul M. Winters, Note, Revitalizing the Sanctions Provision of the Freedom of Information Act Amendments of 1974, 84 GEO. L.J. 617, 618 (1996) (“However, during the sanctions provision’s . . . life, the federal courts have been reluctant to take the . . . steps necessary to invoke the provision. This author found only one instance in which a federal court invoked the provision.” (footnote omitted)). This is in stark contrast to some of the expectations in place at the time of the 1974 FOIA amendments that created the sanctions provision. See, e.g., Robert G. Vaughn, The Sanctions Provision of the Freedom of Information Act Amendments, 25 AM. U. L. REV. 7, 7 (1975) (calling the sanctions provision “potentially . . . one of the most important congressional enactments in recent years”). 111. 5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(4)(F) (2006); see also Winters, supra note 110, at 623. 112. Winters, supra note 110, at 623. 113. Stewart, supra note 13, at 286. 508 THE GEORGETOWN LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 101:493 most of these jurisdictions, the unlawful withholding must be done “willingly” or “knowingly” in order for civil fines to kick in.114 The same typically holds true at the state level for punitive damages and criminal penalties.115 B. THE NEED FOR SPECIAL PROTECTIONS Although these state-level protections are certainly better than their federal counterparts, this Note argues that they are insufficient in cases in which the invocation of FERPA is part of the mix. The lack of consistency among states’ penalty regimes, coupled with the high barriers inherent in making a showing of willful or knowing withholding, provides a weak incentive for schools to comply with open records requests. This is arguably true of all institutions that are subject to open records laws. However, what sets educational institutions apart is the perverse incentive to rely on federal law to deny requests. This section traces this issue to its sources—namely, the temptations to overcomply with FERPA, to intentionally flout open records requests, and to force litigation— and explains why the prevalence of student journalists in FERPA-related cases creates a special problem. 1. Misaligned Incentives Currently, the choice facing a school that gets an open records request is that the school can honor the request and release the documents, or it can cite FERPA and do nothing. The upside to releasing the information is that it could allow the school to honor its obligations under the relevant open records act. Conceivably, the school could also avoid the costs of litigation and any associated fees, such as attorney’s fees and civil penalties. However, these costs are unlikely to materialize. This is primarily because litigation is unlikely to ensue. For instance, at the federal level, a combined twenty-five departments and agencies denied 20,784 FOIA requests in 2004.116 Of those, fewer than two percent led to litigation that made its way through the court system to a final judgment.117 Moreover, of the 2,460 FOIA cases that reached a judicial decision between 1999 and 2004, only seven-tenths of one percent involved media companies.118 These numbers suggest that journalism outlets are unlikely to pursue lawsuits. This reluctance has a number of root causes, including budget shortfalls and concerns that litigation delays would render information stale by the time it is released. For reasons explained below, the aversion to litigation is even more pronounced among student journalists, who are frequently the ones involved in 114. Id. at 287. 115. Id. at 290, 295. 116. FOIA Litigation Decisions, 1999–2004, COAL. OF JOURNALISTS FOR OPEN GOV’T 1, http://www. docstoc.com/docs/52204362/FOIA-Litigation-Decisions-1999–2004 (last visited Sept. 11, 2012). 117. Id. 118. Id. 2013] HIDING BEHIND IVORY TOWERS 509 FERPA-related disputes with educational institutions.119 Moreover, while attorney’s fees are sometimes awarded when litigation does ensue,120 they are often insubstantial costs for well-funded institutions to absorb, and this author has not come across a single case in which civil penalties have been awarded for the improper invocation of FERPA in an open records dispute. On the other hand, the potential downsides to releasing the information are fairly substantial. For instance, the documents could be embarrassing, and their release could hurt the institution’s reputation. Alternatively, if the documents actually are education records, the institution could be putting its federal funding in jeopardy. Consequently, on a comparative basis, the costs of invoking FERPA to improperly deny an open records request are relatively low, and in the likely event that no litigation ensues, they are nonexistent. Indeed, “[i]f unlawfully refusing to disclose a record is not [credibly] punishable by either civil or criminal penalt[ies], but unlawfully disclosing a record [is costly] . . . it does not take much imagination to see on which side [an administrator] would err.”121 Even when requests do not involve documents that could legitimately be considered education records, the cost of denying the requests is low, and the occasional lawsuit is likely less expensive than investing in the resources to properly vet open records requests on the front end. Beyond that, FERPA actually provides an incentive for administrators to force litigation. That is because a judicial decision ordering the release of documents immunizes institutions from the threat of having their federal funding cut off for releasing education records.122 Because the cost of any given lawsuit almost certainly pales in comparison to the amount of federal funding an institution receives, the option of forcing journalists to litigate—which they are unlikely to do—can become even more appealing to institutions that are otherwise on the fence about whether to comply with an open records request. Taken together, these incentives often result in schools staking out extreme positions rather than paying close attention to compliance. Take, for instance, Indiana University, which in the course of FERPA-related open records litigation rejected the notion that it could merely redact students’ information from documents and went “so far as to suggest that if a 1000 page document consisting of otherwise discloseable material contained one line regarding a student’s grade, then the entire 1000 page document must be withheld pursuant to FERPA.”123 While the court wisely rejected that approach,124 it was a low-cost position for the University to advance, and had it not been for that one 119. See infra section III.B.2. 120. See, e.g., Poway Unified Sch. Dist. v. Super. Ct. (In re Copley Press, Inc.), 73 Cal. Rptr. 2d 777, 784 (Ct. App. 1998). 121. See Stewart, supra note 13, at 293 (footnote omitted). 122. See 20 U.S.C. § 1232g(b)(2)(B) (2006). 123. Unincorporated Operating Div. of Ind. Newspapers, Inc. v. Trs. of Ind. Univ., 787 N.E.2d 893, 908 (Ind. Ct. App. 2003). 124. See id. 510 THE GEORGETOWN LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 101:493 particular lawsuit, the University could have continued to deny open records requests on that basis without facing any legal costs. 2. The Special Problem of Student Journalists As explained above, absent a credible threat of litigation from journalists, the incentives strongly favor institutions—either negligently or in an attempt to keep embarrassing information hidden—asserting FERPA when the documents in question are not education records. On the aggregate, the threat of litigation is relatively weak because journalists sue infrequently. The problem, however, is particularly acute given that FERPA frequently arises in the context of open records requests from student journalists. After all, student journalists, whose role it is to cover the affairs of their schools, are the ones most likely to interact with administrators. It is difficult to measure with any certainty how FERPA affects student journalists. Indeed, unless a case is litigated, there is unlikely to be any public record of the underlying dispute. Quantifying the number of student journalists who drop their open records requests after their schools invoke FERPA instead of pushing ahead and demanding access to the documents is like trying to measure the chilling effect of a speech regulation. It is an imprecise estimate of how much activity would have happened in a counterfactual universe.125 In the case of FERPA and open records laws, it involves an inquiry into how many more records would become public in a universe in which educational institutions applied a more equitable approach to open records requests. Despite the difficulty of precisely quantifying the effect, there is good reason to believe that the heavy presence of student journalists in these cases makes the threat of litigation even more remote and thereby increases the incentives for institutions to improperly deny open records requests. Frank LoMonte, the executive director of the SPLC, deals with student journalists on a daily basis. In his experience, students, taken as a class, are far more averse to litigation than professional journalists: “Most students are hesitant to push their school to the wall for public records.”126 According to LoMonte, “[a]s a threshold matter, the vast majority of college journalists go their entire career without filing any public information requests.”127 Those who do file them face “psychological and practical barriers” to challenging the denial of those requests.128 “The psychological barrier is it’s really intimidating to sue your own school,” LoMonte says.129 Indeed, schools have 125. See, e.g., Leslie Kendrick, Speech, Intent and the Chilling Effect, 54 WM. & MARY L. REV (forthcoming 2013) (manuscript at 43) (“It is difficult to establish either the presence or the absence of a chilling effect, let alone to measure the extent of such an effect.”). 126. Telephone Interview with Frank LoMonte, Exec. Dir., Student Press Law Ctr. (Apr. 30, 2012) [hereinafter LoMonte] (on file with author). 127. Id. 128. Id. 129. Id. 2013] HIDING BEHIND IVORY TOWERS 511 been known to “bully [students] into backing down,” says David Cuillier, an open records specialist at the University of Arizona.130 Informal audits of universities’ open-records-compliance records have confirmed this impression. In one study, journalism students in Georgia requested documents from a number of sources, including police stations and universities.131 While the majority of universities complied, students were often “taken aback by rude treatment.”132 The students also reported that universities sometimes “threw up roadblocks” in response to open records requests.133 On the practical side, most student journalists have relatively short careers— after all, college typically lasts only four years—and therefore have little reason to take on lawsuits that will outlive their time at their schools. Moreover, most student publications lack access to sophisticated legal resources and are unable to fund litigation. Consequently, it is highly unlikely that the negligent denial of an open records request will result in a lawsuit. “By far, the vast majority [of potential cases] will never see the inside of a courtroom,” according to LoMonte.134 IV. FIXING FERPA The combination of rampant abuses and misaligned incentives signals the need for a legislative solution to this growing problem. While it is conceivable that this could happen at the state level, this Note proposes a federal solution. To date, most proposed legislative solutions to this problem have focused on amending FERPA’s definition of education records to explicitly limit its applicability. Mary Penrose, the Texas Wesleyan School of Law expert, has led the charge by calling upon Congress to “sculpt a new definition that provides protection only to academic materials and records, not all items within a school’s possession—even fleetingly on an e-mail server—that somehow reference or mention a student.”135 Penrose notes that the current definition is 130. Telephone Interview with David Cuillier, Assoc. Professor of Journalism, Univ. of Ariz. (May 2, 2012) (on file with author). 131. See CAROLYN S. CARLSON ET AL., 2008 GEORGIA STUDENT SUNSHINE AUDIT: TESTING STATEWIDE COMPLIANCE OF THE GEORGIA OPEN RECORDS ACT 2, 11 (2009). 132. Id. at 11. 133. Id. at 12. 134. LoMonte, supra note 126. 135. See Penrose, supra note 10, at 106. Penrose’s proposed definition, which would be codified in place of the current 20 U.S.C. § 1232g(a)(4)(A) (2006), is: For purposes of this section, the term “education records” means, except as may be provided otherwise in subparagraph (B), all official records, files, documents, and other materials, whether prepared, kept, collected or stored electronically, which— (i) contain information directly related to a student’s academic potential, academic progress, or academic performance; and (ii) are intentionally maintained by an educational agency or institution, or any person acting for such agency or institution, in any official school or university file or folder. Id. (footnote omitted). 512 THE GEORGETOWN LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 101:493 “pliable” and subject to manipulation and argues that a revamped definition can help “rein in schools that have inverted the law to protect schools, not students, from embarrassing disclosures.”136 This proposal is a good one, and it would likely have some success in constraining the abuses. However, it does not go far enough. In conjunction with any amendments to the definition of the term education records, Congress should also provide for penalties against institutions that use FERPA to unlawfully withhold documents. Until the financial calculus changes, schools can continue to assert FERPA with little or no cost. To date, however, no proposal has been set forth for how to implement penalties against institutions that abuse FERPA. Penrose notes that penalties might be useful, but she stops short of crafting a mechanism for implementing them.137 This Note seeks to fill that void. In particular, this Note suggests that Congress use its spending power to amend FERPA to allow for these penalties. The amendment would provide for the withholding of a fixed percentage of federal funds from institutions that, without any reasonable basis in the law, misclassify documents as education records in response to valid open records requests. The withholding would take place in the fiscal year after the violation is found. Funding levels would return to normal the year following the imposition of the penalty. The Department of Education’s Family Policy Compliance Office, the same office that determines whether an institution has a policy or practice of disclosing education records, would be tasked with evaluating whether the withholding lacked a reasonable basis. It would have the authority to review a school’s withholding any time a court orders the production of documents after the school had relied on FERPA in withholding them. This Part explores Congress’s authority to enact this amendment to FERPA. Section A chronicles Congress’s Spending Clause powers and the limitations that have been placed on them. Meanwhile, section B demonstrates that amending FERPA to provide for penalties is well within Congress’s authority. This Part closes with some considerations for Congress to take into account when crafting the penalty. Section C discusses the appropriate size for the penalty, and section D justifies the proposed standard of liability—withholding documents without a reasonable basis in the law. A. THE SPENDING CLAUSE: GENERAL PRINCIPLES Congress has a well-documented ability to condition federal funds on recipients’ compliance with prescribed conditions. This authority derives from Congress’s authority to “lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay 136. Penrose, supra note 70, at 1590–91. 137. See id. at 1598. 2013] HIDING BEHIND IVORY TOWERS 513 the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States.”138 Indeed, Congress “has repeatedly employed the power [to spend] ‘to further broad policy objectives by conditioning receipt of federal mon[ies] upon compliance by the recipient with federal statutory and administrative directives.’”139 Congress can use its power to condition federal funding to achieve results indirectly even if it is not permitted to mandate them through direct legislation. For instance, in South Dakota v. Dole, the Supreme Court famously ruled that, even assuming Congress does not have the authority to set a national minimum age for alcohol consumption, Congress was nonetheless permitted to withhold five percent of highway funds from states that did not set their minimum drinking age at twenty-one.140 This power, however, comes with limitations. The Dole Court identified five of them. First, the use of the spending power must be in furtherance of the general welfare.141 Second, the conditions placed on recipients must be unambiguous.142 Third, the conditions need to pertain to a federal interest in a particular project or program.143 Fourth, the ends sought must not be otherwise unconstitutional.144 And finally, the conditions must not be unduly coercive.145 Until the recent decision in National Federation of Independent Businesses v. Sebelius,146 the fifth limitation was more theoretical than practical, as the Supreme Court had never struck down a conditional spending provision on coercion grounds.147 In Sebelius, the Court examined the proposed Medicaid expansion that formed part of President Obama’s signature health care law.148 Under the law, Congress authorized the cutoff of all existing Medicaid funds from states that refused to expand coverage under the program to individuals under age sixty-five who earn up to 133 percent of the federal poverty level.149 Noting that federal Medicaid funding accounts for more than ten percent of most states’ budgets, Chief Justice John Roberts labeled the threatened cutoff “a gun to the head” and an example of “economic dragooning” that crossed the line into unconstitutional coercion.150 Nonetheless, Roberts declined to “fix a 138. U.S. CONST. art. 1, § 8, cl. 1. 139. South Dakota v. Dole, 483 U.S. 203, 206 (1987) (quoting Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448, 474 (1980) (plurality opinion)). 140. Id. 141. Id. at 207. 142. Id. 143. Id. at 207–08. 144. Id. at 208. 145. Id. at 211. 146. 132 S. Ct. 2566 (2012). 147. See id. at 2634 (Ginsburg, J., dissenting in part) (“Prior to today’s decision, however, the Court has never ruled that the terms of any grant crossed the indistinct line between temptation and coercion.”). 148. See id. at 2577 (majority opinion). 149. See id. at 2601 (opinion of Roberts, C.J.). 150. Id. at 2604–05. 514 THE GEORGETOWN LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 101:493 line” to be used in future cases to decide precisely when a funding condition becomes unconstitutional.151 B. APPLYING THE TEST Congress has a rich history of using the spending power to indirectly regulate educational institutions.152 For instance, in Rumsfeld v. Forum for Academic and Institutional Rights, Inc.,153 the Supreme Court upheld the Solomon Amendment, which provides for the withholding of certain federal funds from institutions of higher education that deny military recruiters the same access enjoyed by other recruiters.154 Similarly, in Grove City College v. Bell,155 the Court validated Congress’s enactment of Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, which conditions federal funding on schools’ abstention from sex-based discrimination.156 The Court noted that the argument that Title IX was an invalid use of the spending power “warrants only brief consideration” because “Congress is free to attach reasonable and unambiguous conditions to federal financial assistance that educational institutions are not obligated to accept.”157 Indeed, FERPA itself is Spending Clause legislation, and Congress’s authority to enact it has never been called into question by a court. The only time the Supreme Court has referenced Congress’s use of the spending power to enact FERPA, it did so without even the slightest hint of reservation.158 While the Supreme Court has never subjected FERPA to a Dole analysis, the only possible factor that could raise concern would be the coercion test because the legislation permits the withholding of all federal funds.159 However, Title IX also allows for a complete cutoff,160 and that did not deter the Court in Grove City College.161 Even in light of Sebelius, then, it appears that FERPA is on solid ground. 151. Id. at 2606 (“It is enough for today that wherever that line may be, this statute is surely beyond it.”). 152. See McGee-Tubb, supra note 54, at 1070 (noting that “Congress often uses its spending power in areas of traditional state concern, such as welfare and education”). 153. 547 U.S. 47 (2006). 154. Id. at 58 (“The Solomon Amendment gives universities a choice: Either allow military recruiters the same access to students afforded any other recruiter or forgo certain federal funds. Congress’ decision to proceed indirectly does not reduce the deference given to Congress in the area of military affairs.”). 155. 465 U.S. 555 (1984) (superseded by statute on other grounds). 156. Id. at 575–76. 157. Id. at 575. 158. See Gonzaga Univ. v. Doe, 536 U.S. 273, 278 (2002) (“Congress enacted FERPA under its spending power to condition the receipt of federal funds on certain requirements relating to the access and disclosure of student educational records.”). 159. See McGee-Tubb, supra note 54, at 1077 (“The significant amount of federal funding tied to FERPA raises questions about whether FERPA leaves states and universities no choice but to accept the funds, in violation of Dole’s fifth coercion restriction.”). 160. See 20 U.S.C. § 1682 (2006). 161. See Grove City Coll., 547 U.S. at 574–75. 2013] HIDING BEHIND IVORY TOWERS 515 If Congress can use the Spending Clause to keep education records private, it only makes sense that it can also use the same power to encourage the public release of documents that were never meant to be confidential. Moreover, unlike FERPA’s existing provisions, which can lead to the withholding of all funding, this proposal calls for cutting off a portion of the funding only of institutions that negligently suppress open records requests.162 Consequently, this proposal is even less concerning from a Dole standpoint than the currently enacted FERPA provisions. C. CALIBRATING THE PENALTIES For penalties to work properly, they must be properly calibrated. For instance, if a statute seeks to incentivize “X” and the cost savings to a company that does “not X” are $1 million per year, a fine of $1,000 is unlikely to have much impact on the actor’s behavior. Similarly, penalties must be adjusted based on the likelihood of their imposition. This is so because the “motivation to invest in precautions hinges upon the credibility of the threat of [imposition].”163 Thus, if all drivers who speed were apprehended, speeding tickets could be much less expensive; the markup in price is needed because without it, traffic regulations, which are sporadically enforced, would not have any meaningful deterrent value.164 Given the likelihood that most negligent withholding of documents will never be challenged,165 the penalties must be significant enough to make up for their sporadic enforcement. At the same time, in order to truly deter, penalties “must be more than hypothetical” because in many instances “it is the certainty of punishment, rather than the punishment’s severity, that deters violation.”166 Take, for instance, the current version of FERPA, which authorizes the cutoff of the entirety of a university’s federal assistance.167 Penrose suggests that institutions have learned that the federal government is unlikely to ever impose such a draconian sanction, and that, as a result, what was designed to be the ultimate threat—the withholding of all funding—has been exposed as a bluff.168 Consequently, while the punishment for negligent withholding should be significant, it should not be so harsh that the federal government would hesitate too much before imposing it. In addition, less dramatic penalties are more politically feasible and a better safeguard against complaints of coercion. This Note does not propose to resolve with precision the optimal percentage of federal funds that should be 162. See infra section IV.C for a discussion of how to calculate the proper amount to withhold. 163. Linda Sandstrom Simard, Response, Fees, Incentives, and Deterrence, 160 U. PA. L. REV. PENNUMBRA 10, 13 (2011), http://www.pennumbra.com/responses/09-2011/Simard.pdf. 164. See, e.g., James Gibson, Doctrinal Feedback and (Un)reasonable Care, 94 VA. L. REV. 1641, 1652 (2008) (discussing incentive structures associated with speeding tickets). 165. See supra section III.B. 166. Penrose, supra note 70, at 1597. 167. See supra notes 21–22 and accompanying text. 168. Penrose, supra note 70, at 1598 (“The threat of complete loss of federal funding sounds ominous, until one realizes that the penalty has never ever been applied to any school.”). 516 THE GEORGETOWN LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 101:493 withheld in response to each violation. However, five percent, which was the threatened withholding in Dole, seems to be a reasonable place for Congress to start. D. CHOOSING A STANDARD The final component of the proposal is its standard for liability. The “without reasonable basis in the law” standard is borrowed from the Senate’s initial draft proposal for imposing sanctions on agency officials who unlawfully withhold documents under FOIA.169 The Senate proposed this standard as part of the 1974 FOIA amendments that created the current regime of sanctions available under that law.170 As formulated by the Senate’s draft proposal, it was functionally a negligence standard; thus, sanctions would not attach in the case of “reasonable differences of legal opinion.”171 However, after resistance from the House, the standard was changed to punish only arbitrary or capricious withholdings.172 This arbitrary-or-capricious standard, however, has been an unduly heavy burden on litigants, as have the state-level standards requiring a showing of willful or intentional violations.173 To have any reasonable chance at deterrence, penalties must be credible. Especially at the state level, where penalties often require heightened culpability, it is virtually impossible for a judge to find a subjective bad intent when an institution can plausibly claim that it was merely concerned with the privacy of its students when it asserted FERPA. As such, a different approach is needed. Asking the Family Policy Compliance Office to determine whether an institution has a reasonable basis in the law for invoking FERPA is hardly a departure from the Office’s traditional role. Indeed, to determine whether an institution has a policy or practice of releasing education records, it must have expertise in determining what exactly constitutes an education record that must be kept private. To carry out this task, it has developed extensive regulations, which it can employ when making determinations of reasonableness.174 Notably, the office would not be tasked with interpreting state open records laws; instead, it would only be examining whether institutions are being unreasonably obstructionist under federal law. Nor would the proposal put an unfair burden on institutions, as they would be allowed to demonstrate that they were relying on an interpretation of the law which was reasonable (even if ultimately wrong). Thus, an institution that can cite to relevant precedent supporting its position would likely avoid fines, while one that cannot would be more likely to face punishment. 169. 170. 171. 172. 173. 174. See Winters, supra note 110, at 630–31. Id. Id. Id. at 631. See supra section III.A. See 34 C.F.R. § 99.30–.39 (2011). 2013] HIDING BEHIND IVORY TOWERS 517 CONCLUSION Currently, institutions that overcomply with FERPA have almost no costs to internalize. The financial incentives heavily favor denying open records requests, and there is very little available to balance the scales. This “frustrates the purported policy of openness behind the open government laws.”175 Therefore, it is necessary to provide a countervailing economic incentive, such that institutions will face penalties not only for undercompliance with FERPA, but also for overcompliance. Congress observed a similar set of misaligned incentives when it passed the Clery Act, which makes participation in federal financial-aid programs contingent upon colleges and universities making certain crime reports and statistics available to their communities.176 Evidence of high rates of crime on campus, of course, is not information that a university is likely voluntarily to publicize, as it would incur significant reputational harms. Congress, aware of this problem, observed that educational institutions’ reluctance to publicize the data came at a time when “the proliferation of campus crime created a growing threat to students, faculty, and school employees.”177 To incentivize compliance, Congress not only tied reporting to institutions’ ability to participate in financialaid programs, but also provided for civil penalties against institutions that flout the requirements.178 Imposing penalties on institutions that abuse FERPA would operate in a similar way by encouraging the release of information that would otherwise be kept private. Overreliance on FERPA has come at a huge cost: it stymies investigative reporting and allows universities to operate largely in secret. The proposal, put forth by Penrose and other scholars, to amend FERPA to provide a clearer definition of education records would start to solve the problem, but by itself it would not be sufficient. Abuses have proliferated because the current incentive structure strongly favors overcompliance with FERPA. This Note advocates shifting these incentives through the imposition of penalties. FERPA has become an unpopular law among journalists, but its core goals—which include protecting students’ privacy—remain laudable. The key, however, to a successful marriage between FERPA and open records laws is balance. This proposal seeks to restore that balance. 175. 176. 177. 178. See Stewart, supra note 13, at 293. See 20 U.S.C. § 1092(f) (2006 & Supp. V). See Havlik v. Johnson & Wales Univ., 509 F.3d 25, 30 (1st Cir. 2007). See 20 U.S.C. § 1092(f)(13) (2006).