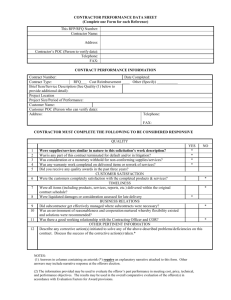

Contract Types: An Overview of the Legal

advertisement