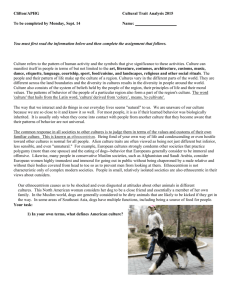

Music: the Cultural Context

advertisement